Leonard, 2006

The first major landmark you encounter when driving into Slab City is a massive, brightly colored mound rising out of the desert like a mirage. This is Salvation Mountain, a Scripture-covered monument created by Leonard Knight.

Leonard rises at dawn every morning to apply fresh paint to his work in progress, but he will promptly drop his paint buckets to lead visitors on a tour, climbing the “yellow-brick road” to the eighty-foot-high summit.

Slab City is a squatters’ community located on a desolate swath of Southern California desert, just a few miles from the town of Niland. Drifters, dropouts, artists, outlaws, and other cultural dissidents have been coming here for more than four decades. They set up camps on the crumbling concrete foundations of a former military base and live in trailers, vans, and buses. Overhead, aircraft from the neighboring bombing range regularly practice military maneuvers, lighting up the sky with tracer missiles and rattling windows with explosions. Some of the residents lead a gypsy-like existence, migrating with the seasons, but most consider the slabs their home.

Electricity in Slab City requires solar panels or a portable generator. Sewage is collected in buckets or holding tanks and buried in shallow pits that are scattered like pockmarks across the desert. Water is hauled in three miles from town. The source is a small faucet at the rear of May’s Store, which also sells food, liquor, cigarettes, and lottery tickets. The local economy primarily revolves around Social Security and government assistance.

Ask people why they are here, and most will tell you they came looking for freedom: from the tension and hazards the urban homeless endure; from rules, rent, and the assaults of a world often unsympathetic to the underclass.

Although Slab City is a collection of fiercely independent individuals, the residents are deeply committed to helping one another. Often those who have extra food or clothing will share with anyone who is in need. If someone becomes sick, neighbors will look in on him or her. Beneath the scarcity in Slab City lie deep reserves of tolerance, generosity, and love.

Ashlee, 2007

Ashlee arrived at Slab City with her family when she was six years old. On weekdays she rode the bus to school in Niland. Her mother found this princess dress for Ashlee to wear trick-or-treating around the neighboring camps. Sometimes in the evening, after the harsh sun had gone down, Ashlee would play and dance like a desert nymph with an entourage of dogs in her wake.

Her family lived at the slabs for two years, then left suddenly, abandoning furniture, clothing, and toys in the dust.

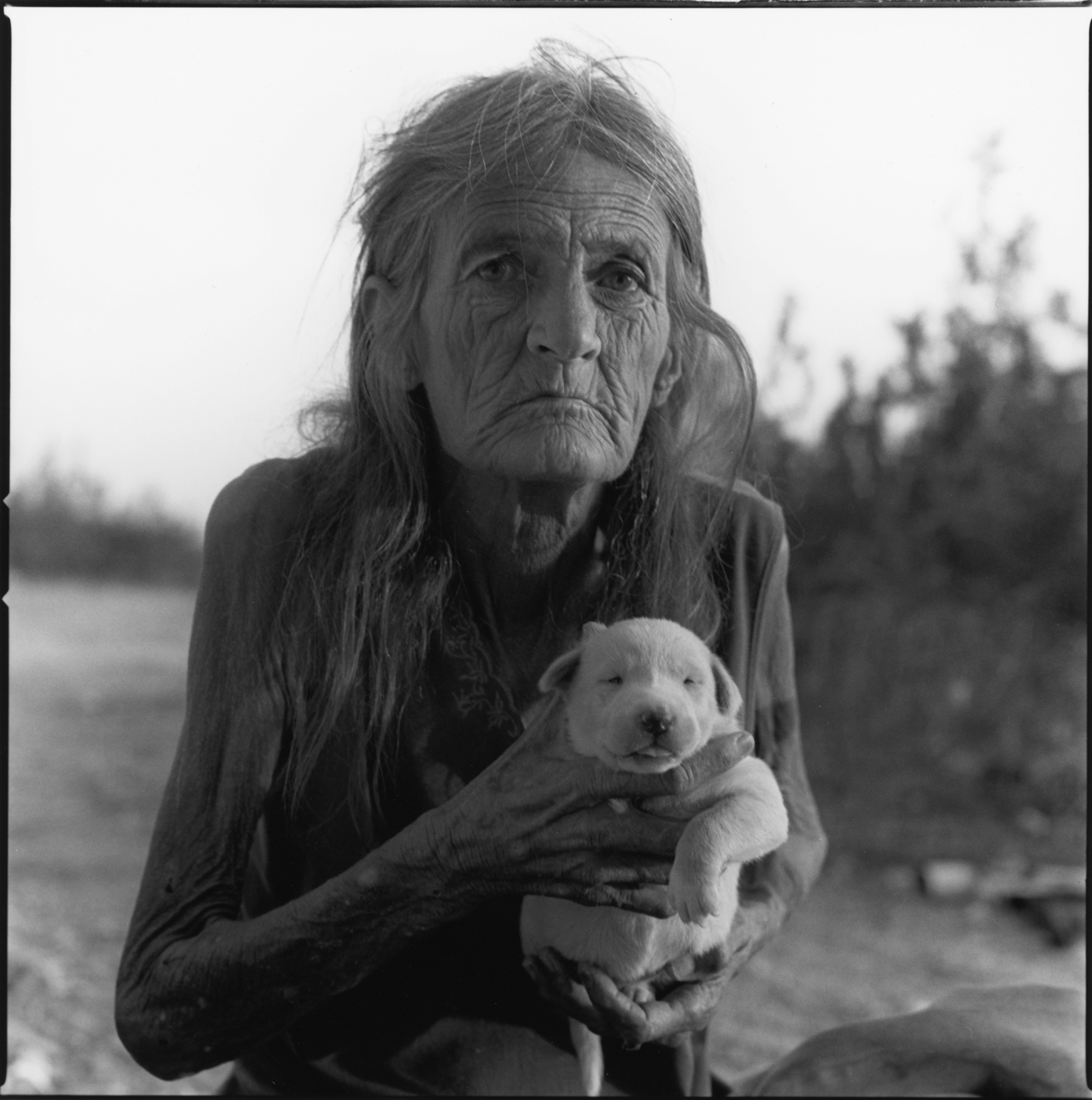

Charlotte, 2008

Charlotte shared a camp with her friend Barbara and her son Judd. Neighbors often came over to drink beer and smoke in the shade of a splendid paloverde tree. Everyone slouched in couches and recliners that encircled a patch of sand so full of cigarette butts it was as if they were sitting on the edge of a giant ashtray. One year I came back and found the camp burned down; the scorched tree hung over the charred trailer.

Charlotte is now living at the edge of Niland, in a tiny concrete house. She is bedridden, and doctors have told her she is dying and there is nothing they can do for her. She says she dreams at night that she is somewhere else, but when she wakes up, “it is all still the same.”

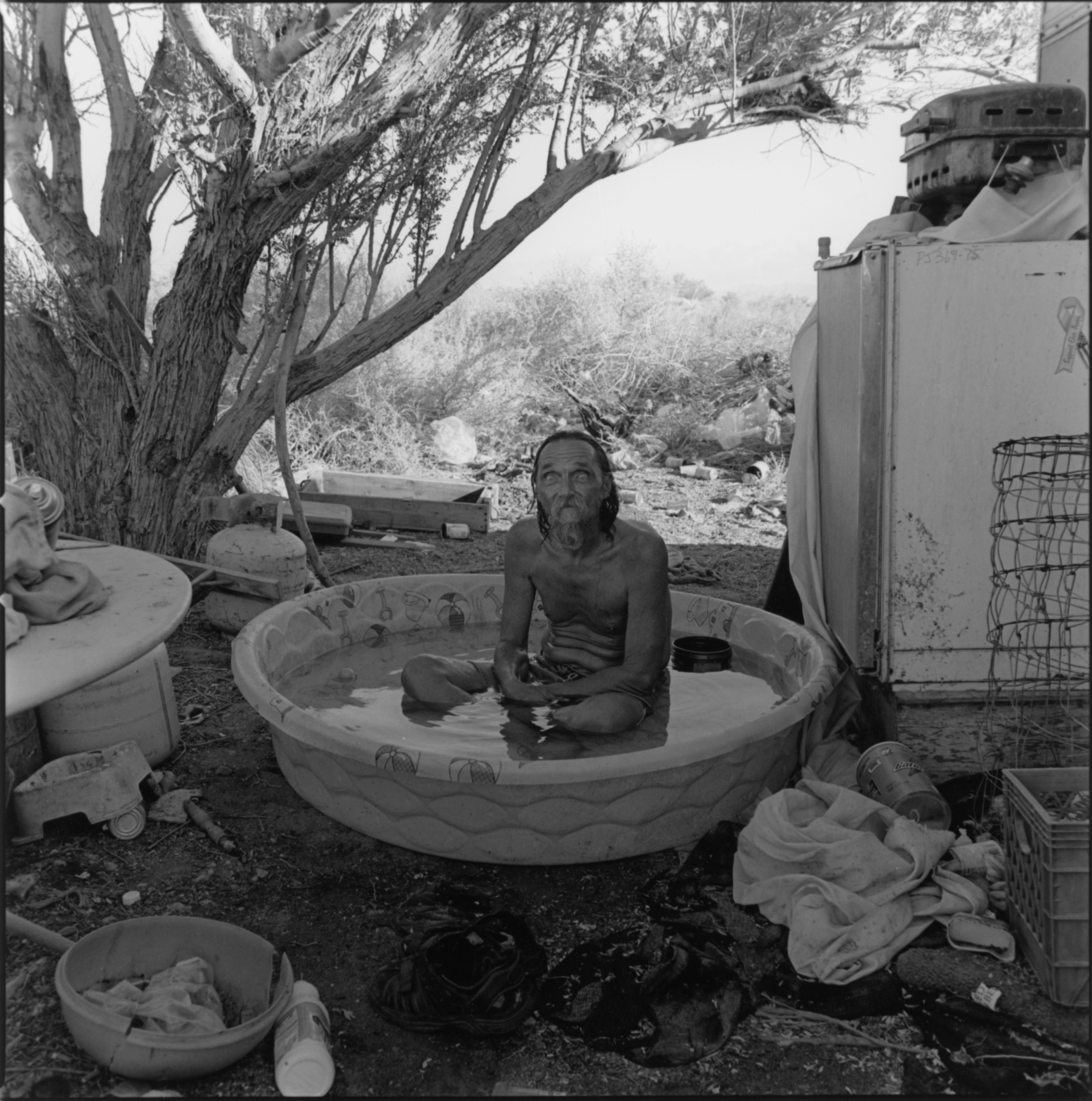

“Insane” Wayne, 2007

Wayne was not really insane. He called himself that because he had enormous blue eyes and liked to look diabolical. He was sitting in his pool for relief from the relentless summer heat.

Although his voice was ravaged by alcohol and cigarettes, Wayne sang soulfully and was a favorite at “the Range,” an outdoor stage artfully sculpted out of old school buses and chrome bumpers, where the Slab City audience alternately supports and heckles the performers while lounging in tattered theater chairs.

Wayne died in his trailer during a heat wave a year after I took this photo. He was buried in a pauper’s grave.

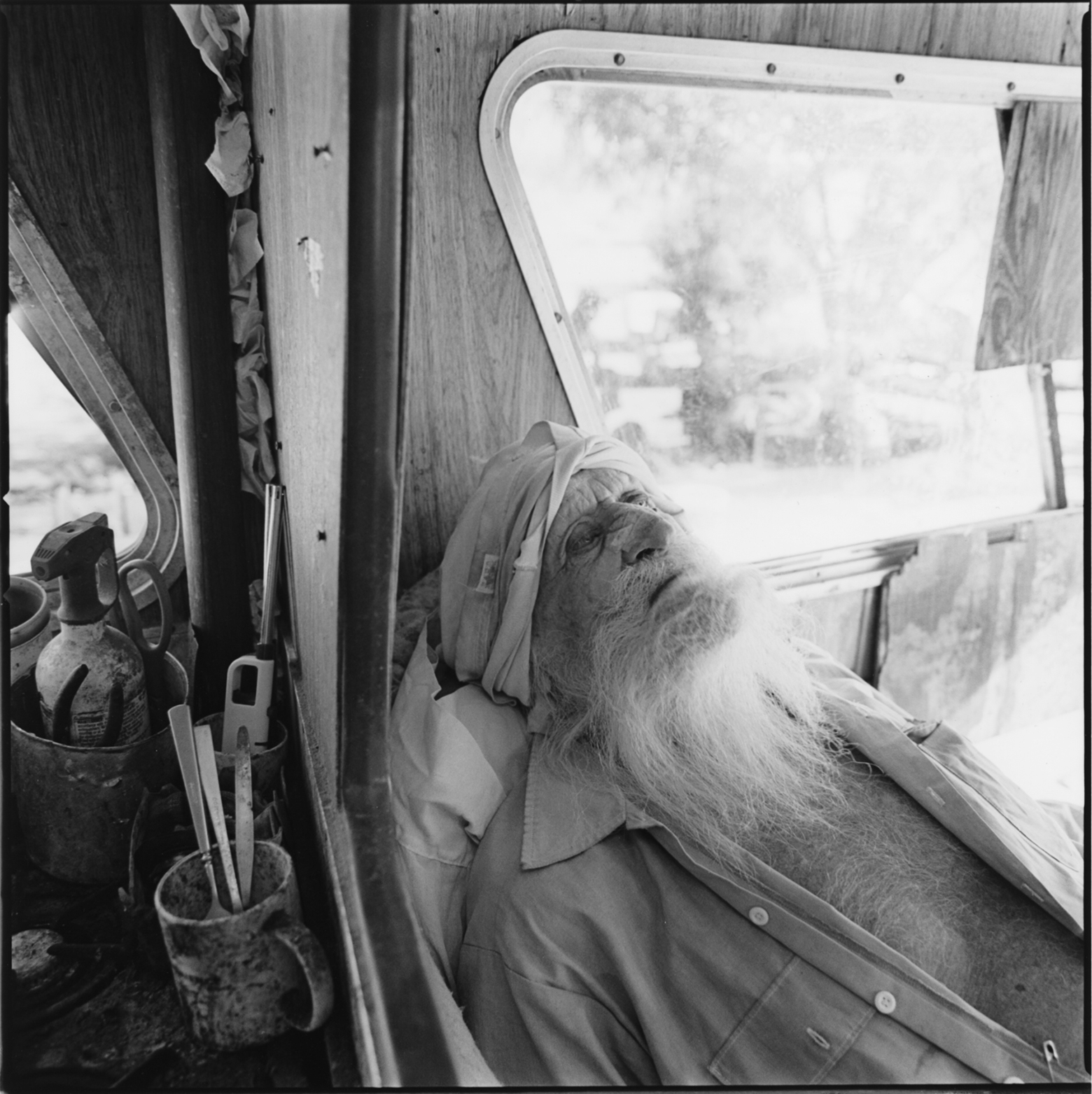

Dave, 2007

Dave turned ninety this year. “I haven’t done a goddamn thing with my life except stay alive,” he says.

After living at the slabs for ten years, Dave, preferring solitude, moved his camp a mile farther out into the desert, where he has a commanding view of the bombing range, an untouched expanse of creosote bush framed by the jagged peaks of the Chocolate Mountains. Attached to the walls of Dave’s antiquated motor home are prints of Van Gogh’s Bedroom in Arles and The Potato Eaters. Stacks of books are everywhere: Thomas Wolfe, Cormac McCarthy, Truman Capote. Dave recently started writing and is always striving for perfection in his work. “Oh, it can never be achieved,” he tells me, “but it must be the goal.”

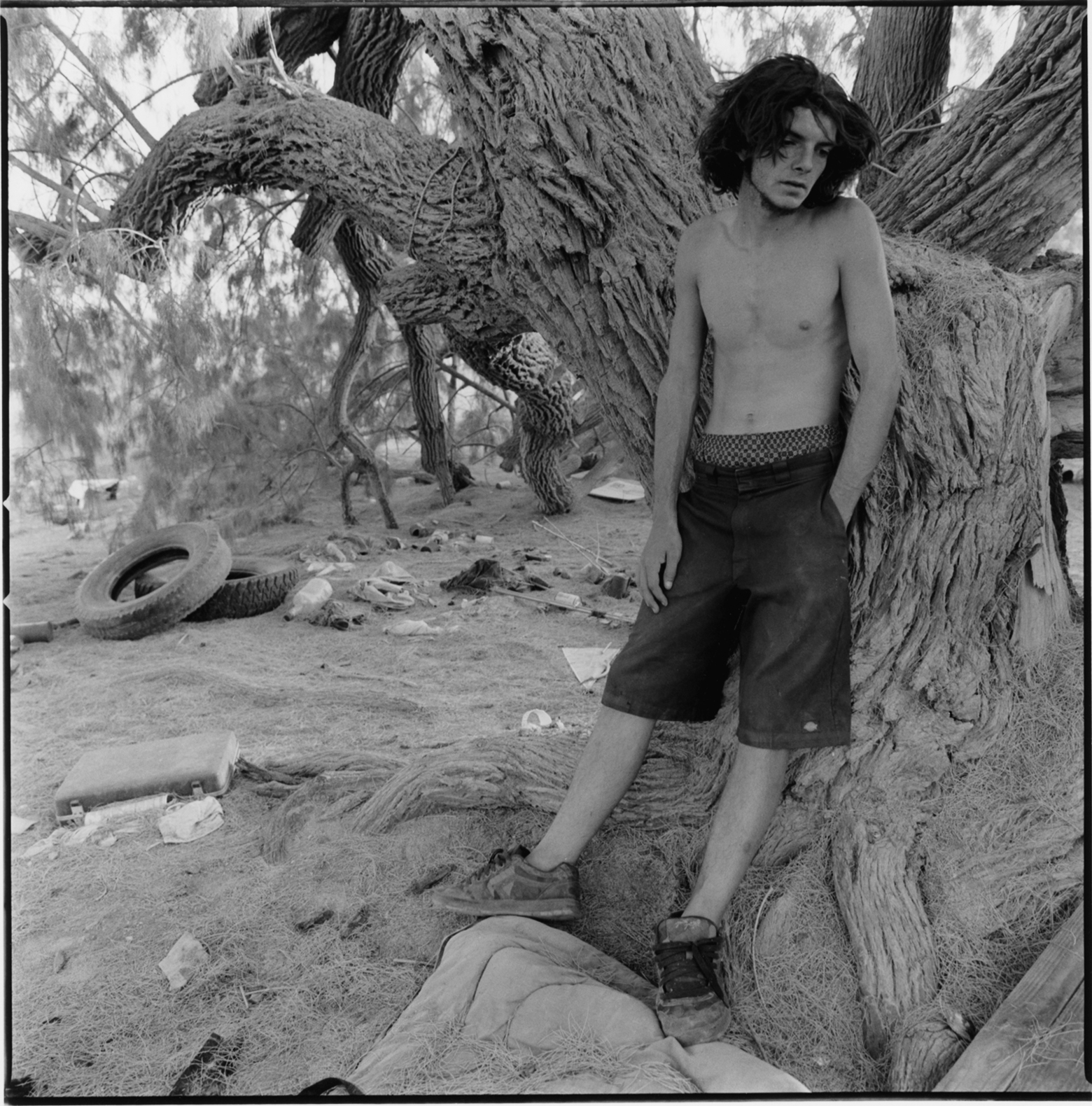

Allen, 2007

Allen was twenty-one when I first met him. He had arrived by bus the night before, his pockets stuffed with truck-stop hamburgers. A lot of idealistic young adults show up at Slab City having renounced mainstream culture. They come here, to a community that unfailingly accepts new members, looking for an alternative. At home they may have resisted authority; here they seek out the elders, gleaning guidance and scraps of wisdom along with food and beer.

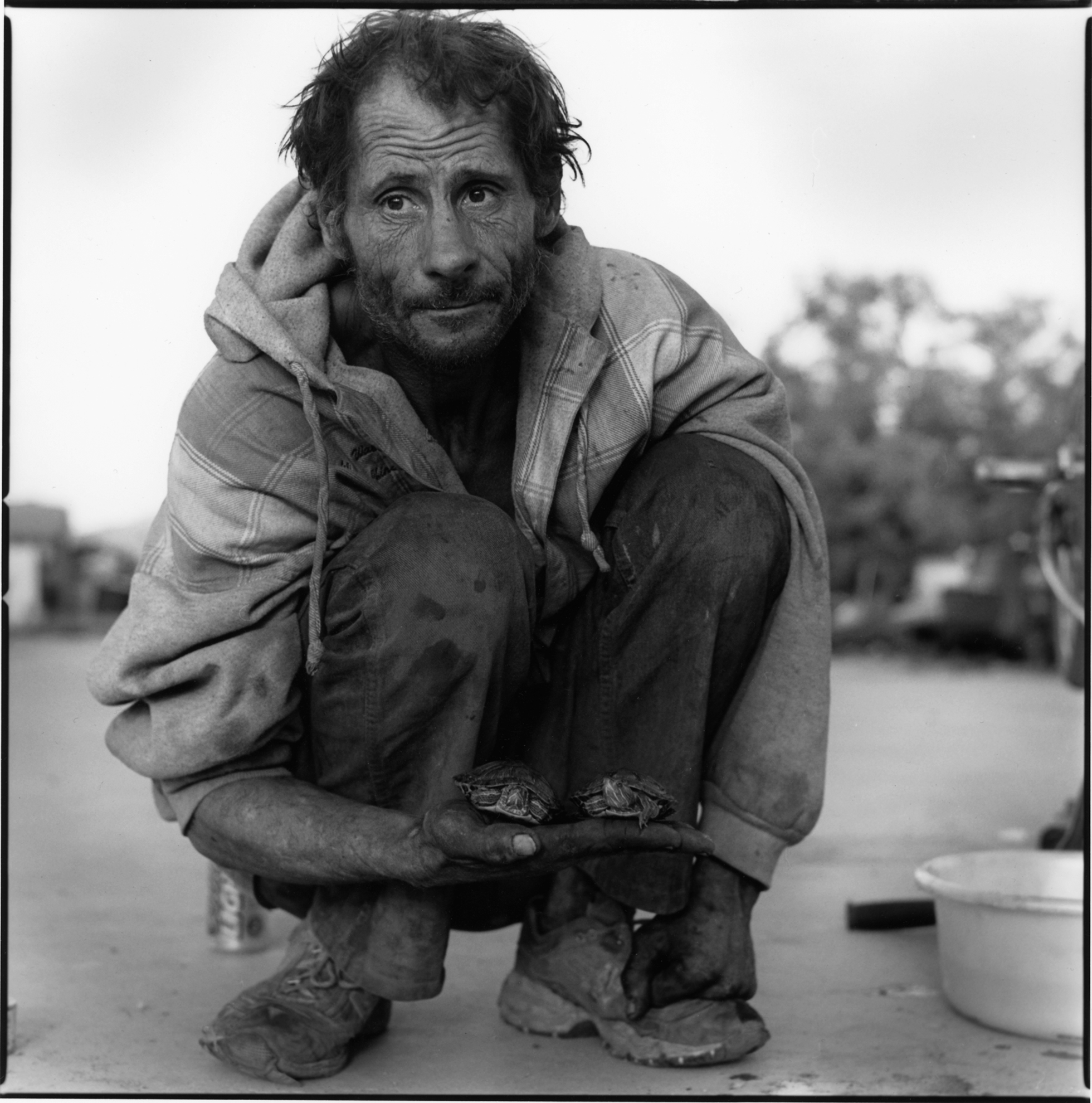

Jerry, 2006

Jerry has a wild, defensive demeanor from years of hardship. Yet beneath it lies a boyish vulnerability and immense generosity.

He has been living at the slabs for twenty-one years. Sometimes he gets frustrated with the people and the heat, so he heads a couple of hundred miles northeast to Kingman, Arizona or over to Oklahoma. So far he has always come back.