Stephen Elliott, whose fiction and nonfiction have appeared in The Sun for ten years, has written a book about the 2004 presidential campaign titled Looking Forward to It, or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the American Electoral Process. While writing the book, Elliott published his rough drafts in an e-mail newsletter. These are some of his dispatches from the Iowa caucus and the New Hampshire primary. The book is due out from Picador in October.

—Ed.

December 8, 2003

New Hampshire

Early this morning I caught an Amtrak into the deep swirl of the election: the last Democratic-primary debate.

I arrived here in Durham, New Hampshire, with no plans, no car, and no place to stay. I guess I figured that someone in the press fraternity would let me crash on the floor of his deluxe hotel suite. But the other members of the press don’t want anything to do with me. They can smell my panic. They keep turning their backs on me or stepping away to talk to someone else. I don’t have an expense account, just an advance from my publisher. The only chance I’ll make any money on this thing is if I can spend less than my advance covering the election, which is no chance at all.

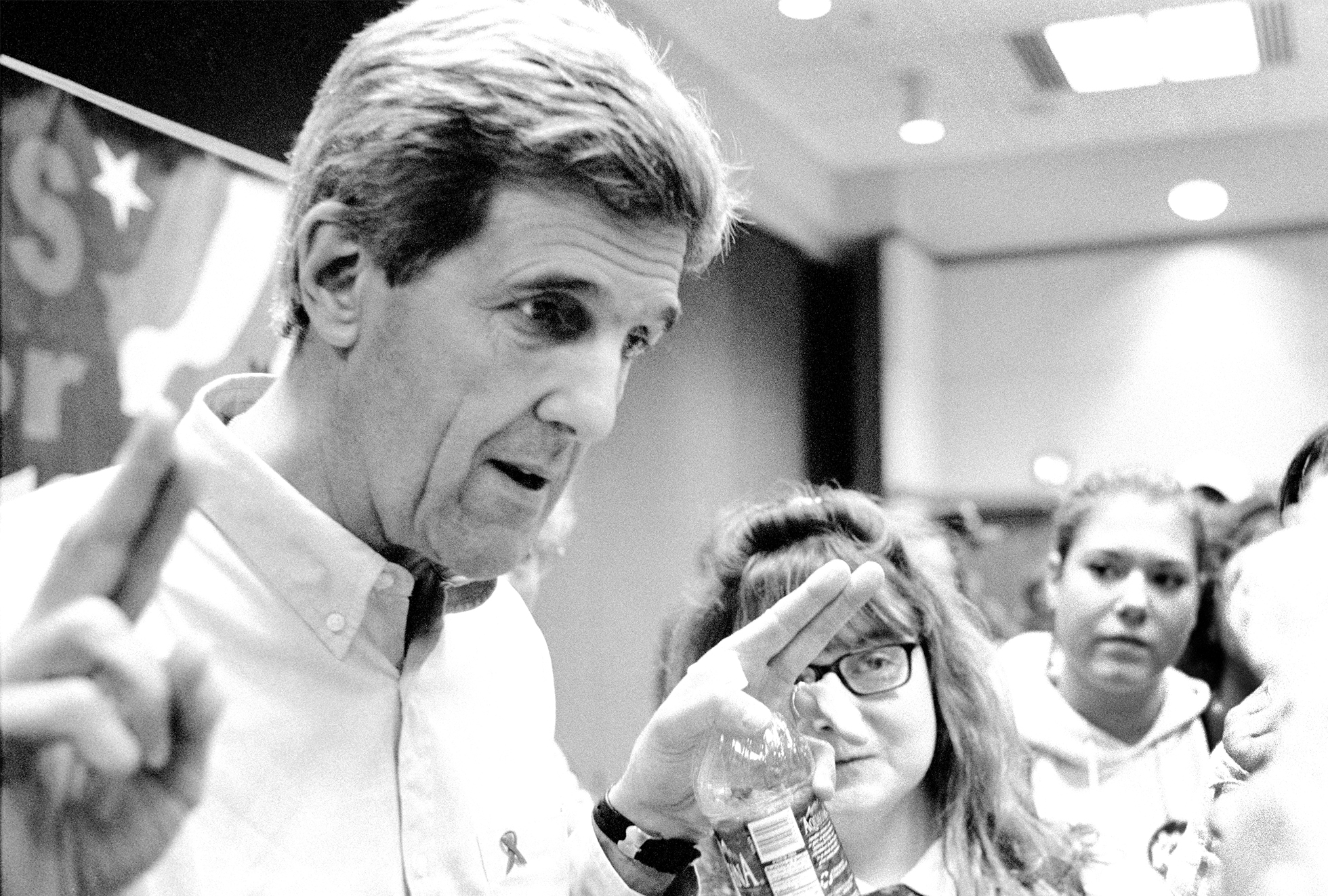

It wasn’t even 7 A.M. when Al Gore announced he’s endorsing Howard Dean. With Dean so far in the lead, his bus is the one everyone wants to be on. It’s always more fun hanging out with a winner. But I feel pulled toward John Kerry right now, who has rented a bus called the Real Deal Express — if his creditors haven’t put a boot on it already. I know it will be a long, slow death bus, filled with bitter journalists assigned to follow a losing candidate. But I’m curious. I want to know what an imploding campaign looks like. I know if I were Kerry, I would party like there’s no tomorrow.

I came out here to cover an election, and suddenly I don’t know if there’s anything left to cover. What happened to John Kerry the front-runner and little Howard Dean biting at his ankles? And what about Joseph Lieberman? Lieberman stayed out of the race until Gore had announced that he wouldn’t run. Now the man Lieberman considered his friend has gone on record as backing Howard Dean. Lieberman must feel like a plane overhead just cracked in half and dumped fifty tons of shit on his campaign bus. How does a person recover from that?

I called my friend Shaila in D.C. to find out how Gore’s endorsement looks from the nation’s capital.

“I wonder what he’s getting out of it,” she said.

“Maybe he wants to be VP again.”

Shaila laughed at my little joke and said, “The New York Times conjectured that Gore is courting the progressive vote. Gore knows Dean’s a loser, and Gore wants to be able to run as a progressive against Hillary in 2008.”

I ventured my own theory. “What if Gore is backing Dean because he really believes in Dean? What if he is backing Dean for no other reason than personal integrity?”

It took a few minutes for Shaila to stop laughing.

“So, let me get this straight,” I said. “You would sooner believe that Al Gore is backing a candidate he secretly hopes will lose than you would believe that Al Gore would make a decision free of political motivation.”

Pause. “Yes. Wouldn’t you?”

“I need more hope than that,” I told her.

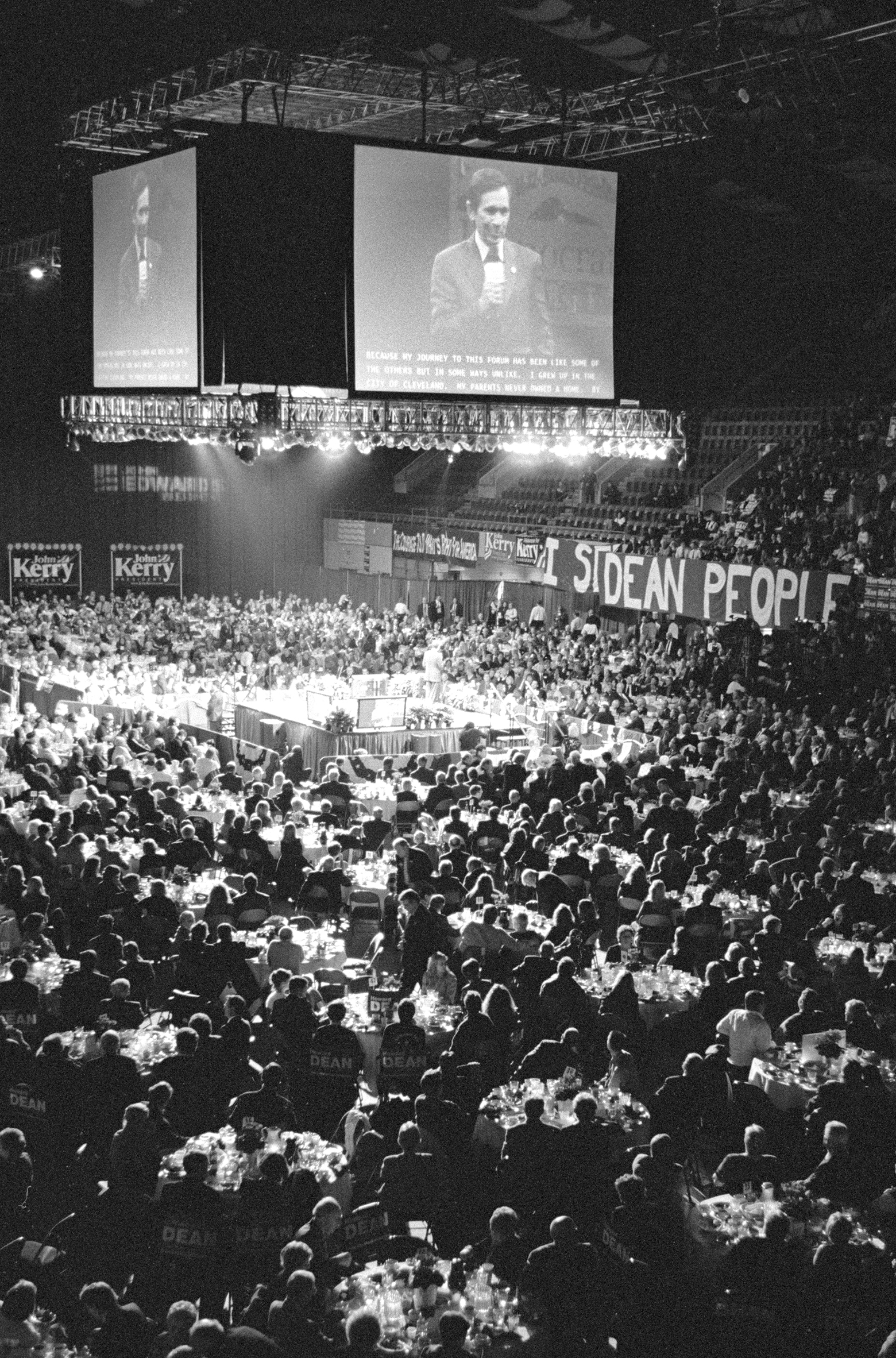

At the debate, the unasked question seemed to be who was willing to bow out first so that a single candidate could mount a legitimate challenge to Howard Dean’s thick-necked juggernaut. Most of the candidates were visibly pissed off by Gore’s endorsement. You could see them thinking, Fuck fat fucking Al Gore.

I can’t blame John Kerry for being angry. He was supposed to win this thing. Kerry said the election isn’t over until the votes are counted, which sounds good but simply isn’t true. Everybody knows the election is over long before then.

John Edwards’s response to every question was that he is an outsider, but his hairstyle doesn’t match this outsider image. Somewhere in the first forty-five minutes of the debate, I realized that Edwards is not the dark horse I thought he was after seeing him dazzle a town hall meeting in Concord, New Hampshire, back in July. It might have been when John Kerry said, “I love John Edwards,” that I lost faith. Every time Edwards said he was an outsider, I heard John Kerry in my head saying, I love you.

Edwards: I am very much an outsider.

Kerry: I love you.

Edwards: I have not spent my whole life in politics, like most of these folks.

Kerry: I love you, man.

Edwards: The question is: Who is in the best position to change what’s going on in Washington: people who’ve spent most of their life in politics, or somebody who’s been fighting these people all his life?

Kerry: I love you so much. I’m so completely into you.

December 13

Iowa

I’ve been with the Kerry campaign in Iowa for two days now. I’m pretending to be “embedded.” When you’re embedded in the campaign, they arrange for your meals, transportation, rooms, and airfare — but they also take your credit card number and bill you for everything. The only way I could afford it would be to tell MasterCard that my card was stolen.

The big news today is that Saddam Hussein has been captured. I imagine he’ll be hauled out wearing a diaper and a bonnet while Bush sneers, “Who’s the big, bad dictator now?” Kerry is downstairs giving a press conference. You just know that Kerry is going to grab for the middle and say that, although Saddam’s capture is good news, it doesn’t mean that we should be acting alone in Iraq.

Today I rode on the official Kerry campaign bus. First we went to a hospital, where Kerry unveiled his healthcare plan before a hundred people. Thirty of those hundred were from the bus, and many of the others looked like hospital workers with nothing better to do. Then we went to a firemen’s union hall, where the buffet table was loaded with seven-layer salad, sandwiches, baked beans, and free beer.

“We’re not supposed to eat from the buffet,” Nedra Pickler of the Associated Press told me. “You don’t want to be compromised.”

“I don’t mind being compromised,” I said, loading up my plate. “I like being compromised. I’m a compromiseaholic.”

I like John Kerry, though I didn’t want to. It’s hard not to like someone you’ve met face to face, because most people are decent underneath it all. But then I see Kerry on TV, and I dislike him all over again. One day he implies that, if he were president, we wouldn’t be in Iraq. The next day he suggests that if he were president, we might have caught Saddam earlier. And he never finishes a speech without taking some dig at Howard Dean. You can feel the room heating up as he talks about Bush: how the president tricked him and other senators into voting to authorize force in Iraq by promising to include other nations and the UN. But then Kerry will finish with “And Howard Dean was also in favor of going to Iraq.” And the air goes out of the room.

I want to shake him and say, “Hey, man, you’re acting like a jealous lover. Be your own man, for Christ’s sake. You’re running for president, not for governor of Vermont.”

But Kerry is stuck. He just can’t believe that little bastard from Vermont is going to get the nomination. Kerry was the chosen one. He was presumptive. Now he’s requesting an endorsement from the Boston Globe, his hometown newspaper. And they may not give it to him.

December 15

The Real Deal Express has been replaced by the Death Bus: a slow ride across the frozen plain, the windows slick with the Iowa winter, the driver’s bony fingers curled around the steering wheel. A thin band of light from the streetlamps illuminates the candidate’s suit coat as he jokes with his supporters. They ask him about his service in Vietnam, what he eats for breakfast, how he keeps going, day in, day out. (None of them completes the thought: “When your campaign is dead as hell.”)

Kerry has the record: He fought in Vietnam, was a hero, and then came back to oppose the war. He led the investigation into the Iran-Contra affair, led the movement to normalize relations with Vietnam, and exposed the CIA’s involvement in drug trafficking and its connection to Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega. He did all the right things, with diplomacy, and then he voted in favor of a resolution authorizing troops in Iraq.

December 19

I’ve made arrangements to join back up with the Howard Dean campaign. I’ve been apprised that I won’t actually be on the bus with Dean. I’ll be in a press van that trails behind the campaign bus. Dean is big-time now. I’ve always thought of Dean as a compromise candidate, but since I’m over thirty, I’m willing to compromise. If I weren’t willing to compromise, I would probably vote for Dennis Kucinich.

To understand Dennis Kucinich, you have to know about Cleveland. Several decades ago, the city was trying to privatize its electric utilities. Kucinich ran for mayor on a platform of keeping the electric company public, which would save the taxpayers money. He was twenty-six years old, and he won.

But then the big boys stepped in and said he had to privatize the electrical system or they were going to cancel Cleveland’s credit. Imagine: a city with no credit. Everyone in both parties told him he had no choice. But he held his ground. It was political suicide. The banks canceled Cleveland’s credit, and for the remainder of his term Kucinich had to run the city on a cash basis. Cleveland held on to its electric utility, but Kucinich wouldn’t be able to get elected again for fifteen years.

“Those were hard years,” Kucinich says, and you can tell he means it. All he wanted in life was to hold public office.

Fifteen years later Cleveland’s municipal electric utility was a success story. Kucinich was vindicated. He won a seat in Congress that he still holds today.

I met Kucinich yesterday at Cornell College, outside of Iowa City. The peace walkers were there, five people who are walking across the country in support of his candidacy. One of them, an emaciated young man with a beard, gave a short speech about hope and stars and enlightenment. There were close to a hundred people in attendance. A woman screamed from the balcony about immigrants’ rights and clapped loudly when Kucinich repeated her position with a little more restraint.

I was surprised there were no other members of the press traveling with Kucinich. ABC apparently pulled its full-time reporter after Kucinich chastised Ted Koppel at the debate in Durham, New Hampshire. (He told him to stop focusing on money and polls and start focusing on the issues.) I climbed into the van with Kucinich, and we went from Mount Vernon to Moline to Davenport to some factory on the edge of a cornfield where they build municipal-vehicle tracking systems, whatever those are. Then it was on to a bookstore, a library, and finally a house party where a young girl played the accordion and sixty people sang “The Dennis Kucinich Polka.”

Kucinich can give a speech off the cuff with the timing of a spoken-word poet. He’s got nothing to lose from working without a script because the mainstream media have already written him off. Why cover a candidate who’s going to lose? Kucinich will tell you that’s a self-fulfilling prophecy, and maybe it is, but it doesn’t give him any more of a chance. Kucinich refers to the media as the “Great Mentioner,” and you can tell it personally offends him that he’s not mentioned. I feel the same way when newspapers don’t review my books. There’s nothing worse than being ignored.

At one point during the day, a man asked Kucinich about his policy for drug addicts and then interrupted Dennis’s answer with remarks like “That’s me” and “You got that right.” This is always a problem for far-left candidates: people show up at their events who are crazy, lonely, and starved for attention. Drug addicts, witches, congressional candidates — they all want to talk about their own issues. And because the leftists are so afraid to offend, nobody says, “Hey, shut the fuck up, you crazy bastard.” You can bet that’s what someone would say at a Bush rally — or at a John Edwards rally, for that matter. Jennifer Palmieri, Edwards’s press secretary, would throw a full-body tackle on the junkie before the networks could reposition their cameras. And everyone would pretend nothing had happened.

On the issues, Kucinich is the only candidate (besides Carol Moseley Braun and Al Sharpton) who’s in favor of universal healthcare, as opposed to universal health insurance — an important distinction. I mean, why give all this money to the insurance companies? How do insurance companies make a profit? By not providing healthcare. And Kucinich is also the only candidate suggesting we leave Iraq within ninety days.

I definitely had a homoerotic moment with Kucinich last night in the van. As I said, there was no one else traveling with his campaign. (Meanwhile, all the major news outlets have assigned ten press people to cover John Kerry, who’s polling even with Kucinich in many states.) I spent ten hours sitting next to Kucinich in the van. If you want to get to know a candidate, that’s the way to do it, with your knees touching. At first we were a little cold toward each other. After all, I’d once called him a “kook” in print and made fun of his veganism. Ironically enough, our moment of connection came during a conversation about diets. I told him I drank too much coffee and had been eating a hamburger a day for the last week. He said he used to drink six cans of Pepsi a day, but then he became a vegan to impress a girl.

“I do things to impress girls, too!” I said.

At the next-to-last stop of the day, one of his supporters showed up with a home-cooked vegan meal, which Kucinich insisted on splitting with me. It was late, and I was tired and feeling a little emotional after listening to his stump speech about peace and love all day. While forking sweet potatoes onto my plate, Dennis talked about transcendent moments. “Your whole life can change in one moment,” he said. “That’s what people are looking for. They spend their entire lives searching for that.” I didn’t realize how dehydrated I was until he handed me a bottle of spring water. The stars outside were so brilliant it looked as if the night sky might explode. I thought I would cry. He said he was running for president because of the war, because war is wrong. “We need to think about reparations for all the innocent victims.”

I thought, Look at the telephone lines between Des Moines and Davenport. Look at America. Just look at it. Would we shed an American tear for the innocent victims of the bombings? When the collateral damage is counted, will it touch our patriotic hearts? Radio Iowa, can you hear me?

It was the best food I’d ever eaten. By the time Dennis was splitting his vegan apple pie with me, we were friends.

“You’re more in touch with your humanity than the other journalists,” he said.

He had no idea.

I won’t lie and say we didn’t hug in the lobby of the hotel. We did. And I realized that I had been compromised. Eating from the Kerry buffet was nothing. Kucinich split his meal with me. I loved the guy.

But not in my most deluded moments did I think he could win.

January 6, 2004

New Hampshire

I’m heading for the nationwide College Convention in Manchester, New Hampshire, to get a handle on the youth vote. I took a couple of weeks off for the holidays, and it seems I didn’t miss much. Kerry continued his negative campaigning, which at this point is about all he’s known for. Ask somebody on the street if Kerry is for or against the war in Iraq. Same with Edwards. The Times ran an article today on how Kerry and Edwards are competing for third and fourth in Iowa. Do they not hear the bells tolling?

The big news recently is Wesley Clark’s refusal to run for vice president. There are times when I think a Dean/Clark ticket is the only thing standing between us and school prayer, private prisons, and mad cow on the lunch menu. And I’ve been worried recently that, with the current deficit spending, there won’t be any Social Security or Medicare when I’m old. I was kind of looking forward to a subsidized retirement in the old folks’ home, wearing my white nightgown and flannel slippers and playing bridge all day.

What’s clear is that this race has boiled down to two men, Wesley Clark and Howard Dean. The Democratic machine is likely to come out for Clark. The real question is: How long will the other anti-Dean candidates hang on by their fingernails, siphoning support from the general?

I plan to spend the next four days figuring out what the youth vote has to say about all this. Perhaps I can bankrupt a couple of young Republicans at the card table while I’m at it, so they can feel what I felt when I was their age.

“Call Daddy,” I’ll tell them as I clean out their trust funds. “Tell him to FedEx your bootstraps.”

Prediction: Dean takes first in Iowa by more than anyone expects. Kerry comes in a distant third and calls it a victory. John Edwards places a sick fourth.

January 8

There are days now when I take speed for no good reason at all, just because I miss my girlfriend or to kill some time. The hotel-room door is bolted shut. I open it only when the bellboy comes by with another packet of Folgers for the four-cup coffeemaker. Sometimes it’s hard to get out of bed because of the jet lag.

The College Convention 2004 is on the first floor of the hotel. Kucinich electrified the crowd today. When asked about NAFTA and the WTO, he said he would pull out of both. He said he would work to rid the world of nuclear weapons, and the kids cheered. I felt bad for not cheering. I wanted to cheer for the idea of a world without nuclear weapons, but I think that would require a lot of trust. Anytime you say to someone, “I’ll show you mine if you show me yours,” you could end up being the only one naked.

I hung out with Kucinich for a few minutes before the event. He gave me a hug. His security guard asked if there was anyone in the crowd I thought he should worry about, and I told him to watch out for Richard Bosa, a fringe Republican candidate. Bosa’s a large man who wears cowboy boots and a trench coat. Somehow he reminds me of my father, which might be why I felt he was a threat.

Bosa was there to take part in a forum called “They Also Ran” with other fringe candidates. I believe there’s something very wrong with anyone who wants to be president, and the truly minor candidates, the ones who have never held any kind of office and have no supporters, prove my point best. They’re the image of the political beast within, stripped of any window dressing or message.

John Buchanan, a fringe candidate from Miami, claimed the Bush administration knew what was coming on 9/11. He also assured the crowd that he was the only candidate who would admit to getting high every single day. (This got major applause.) “After what happened on 9/11,” he said, “you have to.”

January 9

In the morning I slept through Carol Moseley Braun’s speech but made it downstairs in time to catch Kerry’s act. He had twenty campaign workers lined up at the entrance to the hall screaming, “Go, Kerry, Go!” The candidate came down from the dressing room, plowed through his supporters, and went straight to the bathroom. Three guards were immediately posted outside the bathroom so that nobody could disturb the senator. Meanwhile his supporters continued chanting at the top of their lungs, “Go, Kerry, Go!” If that ever happened to me, I would really freeze up.

Kerry didn’t say much new. He gave vague answers to questions from the audience. Pressed for his position on marijuana (as were all the other candidates), he responded that he’s waiting for the results of a new study. The crowd booed.

January 12

Iowa

A week and a day before Iowans will meet in precinct caucuses to select delegates for the party conventions, I meet Josh Bearman at the Eastern Iowa Airport. Josh is writing a piece for the Believer magazine, and we’ve agreed to split expenses. We rent a red Grand Am with a CD player. The guy behind the counter asks if we would like to upgrade to a Saturn SUV for five dollars more a day. I tell him no. I read a New Yorker article that said people drive SUVs because they make you feel safe, and nothing is more dangerous than feeling safe.

There’s a Perfect Storm brewing. That’s the name for the wave of out-of-state Dean supporters arriving this week. They’re coming to get out the vote on Monday and make sure every Iowa resident committed to Dean makes his or her caucus. The other candidates have supporters arriving, too, but not in such large numbers.

Josh and I are staying for a couple of days at a house near the University of Iowa. Today David Redlawsk, a political-science professor and Democratic county chair, invited us to talk to a class he’s teaching over winter break. We were supposed to discuss what it means to be a political journalist, something I know nothing about.

“What if everybody wrote like you?” one of David’s students asked us.

“I don’t know if that would be a good thing,” I told him.

“I usually write about video games,” Josh said.

One young woman said she was working for Kerry. “What do you think?” I asked her.

“We’re not allowed to talk to the press,” she replied.

“You should fail her,” I told David later in his office. “That’s the problem with those campaigns, their top-down management style. You should write it on her transcript: ‘Any press is better than no press.’ ”

David laughed but didn’t agree.

January 14

Here’s what it’s like covering the campaign on a shoestring: Sometimes, when you’re staying at the home of someone you’ve never met and there’s only whole-bean coffee and no grinder, you have to improvise. You start by boiling the beans in a pot, but it takes an hour, and the coffee comes out light and creamy-looking and slightly sour. It’s almost noon, so you slice the wet beans into thirds, careful not to slit your fingertips, and put them back in the pot. The beans are slippery, though, and some shoot from your grasp and roll beneath the refrigerator. After another twenty minutes of boiling, you fish out the pieces and spoon them into a filter, which you place in the coffeemaker. Then you pour the brown water over the mush. You spill a lot and end up with only half a cup and a mess to clean. Your host will be home tomorrow. Luckily you’ll be long gone by then.

Once you’ve had some caffeine, you start to think a little clearer. You miss your girlfriend. (She sent you a picture yesterday from some party she went to. In the picture she’s wearing a latex bikini over a body stocking. In the background is a man in leather chaps; his ass is showing.) The campaigns won’t let you back on the bus because the bus is full. It was easy to get on before, but that was then. This is the big time, buddy, and you and whatever third-rate organization you work for aren’t worth the time of day.

Last night you were drinking with a woman from Iowans for Clark, a former actress who moved to Iowa to pursue a degree in creative nonfiction. She’s a vegan and has a triangular face. You tell her that vegan babies die easily; children need milk. She loves Wesley Clark because he looks great in a Speedo and “he’s the only one who can beat Bush.” (Every candidate, it seems, is the only one who can beat Bush.) She doesn’t like Dean, but she’s not sure why. Before your ride left, you asked if she was going your way, and she said she was, but you didn’t know she meant walking. So you walked to Muscatine at three in the morning and nearly froze.

January 15

I’m outside a Howard Dean rally at a community college. The door is propped open with a chair, and the candidate is speaking inside. It’s his fourth event of the day.

Dean hits his usual planks: healthcare, education, wars based on lies, a Bush clean-air initiative that cuts down trees. This close to the caucus, the candidates don’t take questions. The big news is that John Kerry advocated abolishing the U.S. Department of Agriculture a few years ago — at least, according to the Drudge Report. Iowa Communications Coordinator Sarah Leonard confirms it. She also informs me that the Iowa bus tour covers 631 miles.

CNN says Dean is slipping. Everybody has been saying this. The latest polls show John Kerry winning Iowa with 24 percent, but nobody trusts the polls this close to election day. Dean’s campaign manager, Joe Trippi, tried to dismiss the polls last night. The Kerry camp, he said, has identified every name on the Democratic list committed to caucusing for Dean, and has robo-called them so many times that the Dean people have stopped picking up their phones.

But I’ve been asking Dean supporters, and nobody’s received more than one or two automated calls a day. Most receive only one automated call a week.

In Des Moines yesterday, I went by the Perfect Storm office and saw the volunteers in their bright orange hats, the sleeping bags on the floor, one entire room filled with trash. And I thought, No other candidate could inspire people to do anything like this. But the Perfect Storm volunteers don’t actually live in Iowa, so they can’t vote here. Meanwhile CNN still has John Kerry in the lead. A magazine article said Dean is angry, and then someone else said it, and now the only question is “Hey, man, why are you so angry?” My girlfriend calls and tells me, “Calm that man down!”

Why is Dean so angry? My first reaction is: Why not? I’m angry too. I don’t have health insurance. But then I start to think he’s not as angry as people are saying. He’s less angry now than he was in July. He’s been softening his image. He even wears sweaters.

January 18

Zephyr Teachout, the woman responsible for Howard Dean’s Internet initiative, slept on my hotel-room floor the other night in an effort to save the Dean campaign money. Tomorrow’s caucus is shaping up to be a referendum on grass-roots politics.

Here are my final predictions. (I think it’s important for reporters to make predictions; otherwise all you have is objective journalism.)

Howard Dean: 24 percent or better.

Richard Gephardt: 19 percent.

John Edwards: 19 percent or better.

John Kerry: 2 percent or less.

I have big money on the John Kerry number in a bet with a reporter who’s been on the Kerry bus for months.

January 19

Iowa caucus day

Less than a third of the people who will vote in the general election are expected to caucus today. The streets of Des Moines are nervous. The experts are all declining to speculate. The major newspapers are suddenly saying, “Don’t look to us,” as if encouraging people to come to their own conclusions. Joe Trippi is telling people Dean may come in fourth with 18 percent. The only person sure to win is John Edwards, because no matter how well he does, it will be better than anybody thought.

Edwards has ratcheted his message so tight that he sounds like a Baptist preacher at a revival meeting. At the rallies yesterday, people hollered when he proclaimed he would “cut the lobbyists off at the knees.” Two women fainted. Hundreds waited in the room next door, and anybody who walked in undecided walked out rooting for Edwards.

Kerry’s rally was just the opposite. It went on too long, and people left before the senator even took the microphone. There were twenty to thirty politicos onstage with him, as well as his wife and children, and the emcee sounded like a wrestling announcer: “And now, your Polk County Democratic leadership. . .” Gary Hart and Ted Kennedy were up there. It was the big Democratic machine leaving its wheel prints across the rich Iowa soil. I felt guilty for eating one of the corn dogs in the press area. If I’m not going to say something nice about a campaign, I feel that I shouldn’t eat their food.

This morning my e-mail inbox was filled with hate mail because I called journalist Matt Drudge a “scumbag” in the San Francisco Chronicle. I guess you shouldn’t pick a fight if you’re not willing to see it through. Drudge put my article up on his website, and now I’m getting e-mails from his supporters in the conservative press telling me what a dumb liberal I am. These strong-arm tactics really work. I saw it happen when I was in Israel: you can have ten people waving peace signs, but it only takes one guy swinging his fists to break the whole thing up. That’s why the Right so often wins: they’re street fighters.

The best moment of the night was Chuck Berry performing for Richard Gephardt’s rally. It was all union members, and the beer was flowing. Outside the hotel, Teamster trucks circled like buzzards around a dying calf.

The audience at the Gephardt event looked just like the people I grew up around in Chicago. When I was eighteen, I got kicked out of the group home where I lived, and I moved in with my friends Benny and Jason and their mom and her boyfriend. I lived in their basement for nine months while I finished high school. It was a blue-collar household. Their mom made eight dollars an hour working for a Catholic charity, but she cooked good meals from cheap ingredients and didn’t ask me for rent. I gave her money sometimes. Benny and Jay eventually went into the heating-and-air business, and their sister Chrissy joined the pipe-fitters union. One thing I’ve known for a long time is that poor people are much more likely to give you a place to stay than rich people are.

After Chuck Berry was done playing, he sat on a table and signed autographs for the union guys. Then he fell off the table.

January 20

It’s the day after the caucus. The convention center where everyone filed their stories last night was nothing but cables and wires by eight o’clock this morning. The only journalists left are the ones who missed their flights. The hotel lobbies are empty, and the campaign offices are stripped of anything that can be sold for more than a dollar. Everything’s been stuffed into boxes, wrapped in tape, and shipped overnight to New Hampshire. The only people in line at the coffee shop are the governor of Iowa and a reporter from the Des Moines Register.

I thought I would hang out and try to relax, but I’m already feeling the itch to go east. Maybe I should go home to San Francisco for a day or two. I miss my girlfriend, but she wouldn’t want to see me the way I am now, a depraved and obsessed political animal. Or maybe she would. She likes it when I cry.

I woke up this morning wound tight as a drum and stone sober, a map of Iowa lit like a computer screen across the back of my mind. There was a moment between sleep and waking when it was still January 19 and I could see every precinct and knew every delegate’s name and was in every caucus in the state. It was like watching a house burn.

Iowa voters picked Kerry and Edwards, surprising everybody, and embarrassing me in particular. Really, I shouldn’t be surprised. My political predictions are always wrong. Smart people don’t make predictions, but I’m a gambler. I don’t see any reason to change.

The youth vote stayed home, as everybody said they would. Meanwhile, both of last night’s winners voted for the resolution authorizing force in Iraq, both voted for the Patriot Act, and neither wants to kill the Bush tax cut; they just want to make it more fair, which is nice of them, considering how wealthy they are.

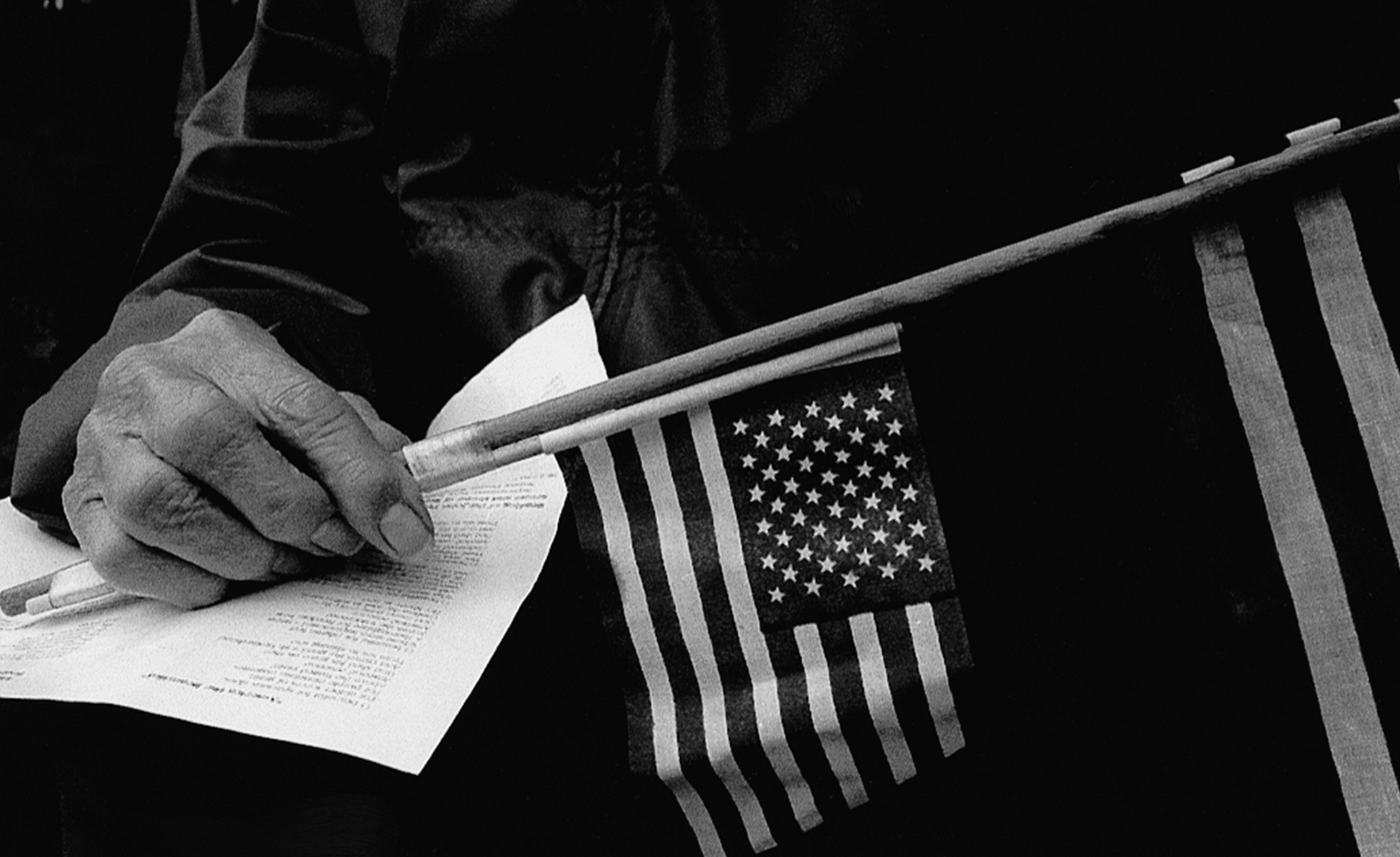

A caucus doesn’t make sense until you see it. Each precinct is awarded a certain number of delegates. To get a delegate, a candidate has to win 15 percent of the room, rounding up. At the caucus I observed, there were forty-nine caucusgoers. Fifteen percent was 7.2, so you needed eight votes to get a delegate. There were officially four delegates, but if six candidates had received 15 percent, there would have been six delegates. If “undecided” gets 15 percent, there’s an undecided delegate. In 1976 Jimmy Carter did not win Iowa; undecided won Iowa.

The crazy thing is that, although it takes just 15 percent to get one delegate, it takes 50 percent to get two delegates. In Precinct 43, where I was, the three Kucinich supporters threw their votes to Edwards, pushing him over 50 percent.

“Why are the Kucinich supporters going for Edwards?” I asked Josh.

“The deal is done,” he said enigmatically, crossing his arms and nodding his head.

This morning my mind was still on the Kucinich-Edwards deal. I called Kucinich’s headquarters from my cellphone. An aide answered the phone. “What I’m about to say is completely ridiculous,” I told him. “You’re going to laugh. But I heard you put the word out to your caucusgoers that if they were not viable, they were supposed to join John Edwards.”

“Well,” he said, “it’s both simple and complicated.”

“Yeah?” I said.

“You know you need 15 percent to be viable?”

I let him keep going.

“We made a deal with the Edwards people that if they weren’t viable, they would join us, and if we weren’t viable, we would join them.”

I stopped on the cold street. It was warmer than it’s been for the last few days, but you could still get frostbite if you talked too long on a cellphone without gloves. I asked the Kucinich aide to repeat what he had just said, and he did, word for word. He waited for me to ask him another question, but I didn’t have any more questions. It hurt.

Have you ever had one of those moments when your self-image completely changes? I thought I had grown cynical and bitter, but this morning I suddenly realized I was idealistic and naive.

Edwards, who was viable in just about every caucus in the state, made a deal with Kucinich, who was viable in almost no caucuses, to trade unviable caucusgoers. Kucinich had plenty of unviable caucusgoers, and Edwards had very few. Edwards got the farm; Kucinich got nothing. All the time Kucinich spent in Iowa, he was basically working for Edwards. Ideologically, it would have made more sense for Kucinich to partner with the Dean camp, but Kucinich had decided to play politics.

After all the candidates’ parties last night, I went to Lucky’s Pub, which is located between the Dean office and the Edwards office. “There are no Republicans in this bar,” one of the Dean workers said. They raised their glasses and put their arms around each other. “It’s all Democrats here.” Then they started to chant, “No more Bush! No more Bush!” Across the room, the Edwards camp began to chant, “Go, Edwards, Go! Go, Edwards, Go!” and the Dean supporters were quickly drowned out.

January 22

New Hampshire

The entire Iowa circus has transplanted itself here to New Hampshire. There are camera crews roaming the halls of the Manchester EconoLodge. Two miles away, across the river, is the Holiday Inn, where all the action is, but the few rooms left there are going for two hundred dollars a night, and that’s too much to pay to stay anywhere in New Hampshire.

The rooms at the EconoLodge are large and have a fridge and a microwave. They’re meant for living by the week, and maybe the weeks will become months, and maybe the months will become years, until one day you get caught doing something you shouldn’t, or you get on a bus and go far away. The thing I like about hotels is that you never have to make a commitment, and you never have to say goodbye.

Everyone is still talking about Dean’s over-the-top caucus-night victory speech in Des Moines. (Though 18 percent was an undeniable defeat, Dean declared the results a victory; all the candidates except Gephardt declared victory.) The press is calling it a public meltdown. But I was at that event with Josh. None of the reporters who saw Dean’s speech stuck around to file a blistering exposé on his caucus-night crackup. They saw a candidate addressing thousands of disappointed campaign workers, who responded well to Dean’s “Yeeeahhh!” But the reporters in Washington, D.C., and New York City, who watched the speech on TV, saw something else.

“How about that yell?” they said.

“Strong stuff.”

In the morning Dean’s “Yeeeahhh!” was all over television and radio.

The night before, though, the reporters didn’t even stick around after the speech. They were eager to get to the winner’s party at the Fort Des Moines, where the liquor was top-shelf and free, and the appetizers came with toothpicks. An hour after the biggest story of the week, the press area was empty, nothing but thirty phone lines hanging from a corkboard ceiling. By 11 P.M. the filing center was deserted, and it was just supporters drinking beer, saying goodbye, and making out.

When Dean spoke on caucus night, he was talking to the kids in the orange hats who had been knocking on doors all weekend, the Perfect Storm. They had come from everywhere, but their presence had hurt more than it had helped. People in Iowa didn’t like to see unshaven kids at their door holding clipboards.

The Kerry office did things differently: a handful of veterans on the phone, a target for each district, a war room lit with lights. When a precinct became viable, a blue light went on, and the word went out to shift efforts to the next precinct. Very organized, very slick. No dirty hippies in orange hats.

The word on the street now is that Dean is finished. Gephardt’s Teamsters are wheels-up across the northeast. Kerry and Edwards are very much in it, though everybody thinks Edwards is running for vice president. Josh and I have our room at the EconoLodge, and last night at 2 a.m. we snuck up to the seventh floor of the Holiday Inn and charged sixty dollars’ worth of wireless Internet to a major television network’s tab. This is outsider journalism, guerrilla style.

January 25

Iowa was on fire, but only in Des Moines. In New Hampshire, primary mania is statewide. You’re never more than forty minutes from a rally or a chili feed.

It’s hard to watch Dean right now, because I liked him more when he was rattling off the states he was going to win and then shouting, “Yeeeahhh!” to an enthusiastic crowd. But that’s just me. I’ve never voted for a winner.

Still, I love politics. I would sleep in a hallway to hear Wesley Clark connect unemployment to family values, or to hear John Edwards say he’s going to “cut the lobbyists off at the knees.” At a Democratic dinner in Nashua, Kucinich unveiled his new rap song: “I’m a patriot / Can’t you see? / I can’t believe / you’d name a missile after me.” By the end I was so high on political juice that my own problems had melted away.

Josh and I have discovered that fringe candidates John Buchanan and Dick Bosa are sharing a smoke-filled room three doors down from ours in the EconoLodge. I was surprised to see them together. They’re both still running, but Dick is also working as John’s campaign manager. The room looked as if two junkies lived there. Dick said he doesn’t want to run after New Hampshire, except maybe in Texas. John writes online articles about himself under the pseudonym Omar Suarez, which is the name of the character in Scarface who gets pushed from a helicopter with a rope around his neck.

An Edwards rally resembles a college football game. There are hundreds of people who can’t get into the room. There’ll be three times that many or more, however, when Kerry shows up just down the road two hours from now. I took some informal polls and found that 80 percent of the people at an Edwards rally are undecided, whereas 80 percent at a Dean or Kerry rally are voting for the candidate they came to see.

Edwards is so sincere you would never know that he’s delivered the same speech five times a day for months. Kerry’s events are still painful for me, but he’s gotten better. Dean is still softening his tone and wearing sweaters. I asked Kucinich about trading unviables with John Edwards in Iowa. He shrugged and said he wanted delegates.

At a Democratic dinner, Dean used most of his seven minutes to thank half the people in the room. He was responding to criticism that he hadn’t thanked the Iowans before he left the state. I love hearing a speech and knowing where it came from. Following the ins and outs of a campaign is like taking the jittery pulse of a country with an unelected president in a time of war.

Politics is about holding people accountable for their record, but it’s also about listening to what they say, and separating the politics from the person. You never get it until you’re on the inside, and even then you don’t get it. But there are days when the roar is so quiet and clean it’s like being inside a wave.

January 27

New Hampshire primary day

Dean’s New Hampshire party barely resembled the caucus-night event in Des Moines. There were no four thousand out-of-state volunteers, no kids in orange hats. There was a VIP party behind a blue curtain and a gymnasium packed with local supporters. The results came across the wire: Dean took 26 percent and Kerry 38. John Edwards fought Wesley Clark to a statistical tie for third.

The Union Leader immediately ran a front-page story declaring that Kerry had buried Dean. But 26 percent is a reasonable showing, especially in a primary.

Dean gave a great speech this time. It was thoughtful, and he remained calm, even when the crowd screamed and pumped their fists. Dean said, “We can give the 50 percent of Americans who have quit voting a reason to vote again, and we will.”

January 28

All the signs are pointing toward John Kerry as the Democratic nominee. Howard Dean has fired Joe Trippi and hired Roy Kneel, a serious Washington insider, to run his campaign. It turns out Trippi gave Dean some advice the night of the Iowa caucus: as Dean headed toward the stage, Trippi told him, “When you’ve got nothing, you’ve got nothing left to lose.” But Dean had a lot to lose, starting with New Hampshire. Dean didn’t even have a speech ready on caucus night; nobody had written one for him. The result was the Yeeeahhh! heard around the world.

John Kerry has never made those kinds of mistakes. He’s always had the best handlers money can buy. And nobody has ever expected Kerry to run as an outsider, so nobody gets mad when he turns out to be just another politician. If he keeps going the way he is, I’ll be spending a lot of time with him between now and November. And that’s going to require more speed than I can currently afford. One reason reporters go easy on Kerry is because the boredom saps their strength. By the end of the day they don’t have the energy left for invective. The easiest thing to do is just quote from the speech and go to bed.

A long time ago I used to shoot heroin. I did it maybe twenty times over a period of a year, leading up to a massive overdose. Even before the overdose, when I was shooting up on an infrequent basis, heroin tended to wipe me out. One night I had shot half a bag after my shift at the Heartland Café, and my friend’s sister showed up wanting to see Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers.

I was on the nod as the movie was starting, fading in and out of consciousness. Then Woody Harrelson and Juliette Lewis went on their killing spree, and I sat upright. The movie had everything: sex, murder, violence, action. To top it off, it was edited like a soft-drink commercial on MTV. It was such an assault on the senses that I couldn’t fall asleep, not even on dope.

I imagine traveling with John Kerry for eight months will be the opposite of that.