For you were for me the measure of all things.

— Franz Kafka, Letter to My Father

Shoulder down, chin out, my father dragged his old athlete’s body down the sidewalk and up the steps to my flat. Refusing any help with his suitcase, he entered, looked around, and exhaled. “I don’t know what you got me into, but here I am.” Though he intended it as a joke, it came out as a challenge. He was nervous. So was I. Surrounded by the general disarray of my single life — books, bikes, West African art, student papers — my father and I were alone together for the first time in as long as I could remember.

“You got any beer in that fridge?” he blurted, eager for a drink.

He looked tireder and older every time I saw him: his hair ever whiter, his six-foot frame smaller, his expression less intense, his brown eyes a little more serene.

Before I could stop him, he’d opened the kitchen cabinet where I stored my growing collection of pills.

“Jeez, it’s like a drugstore in here,” he sputtered, trying to cover his embarrassment. He quickly closed the cabinet, forgetting to take out a glass, while I buried my face in the refrigerator. “That medicine still working?” he asked.

Grabbing two beers, I mumbled, “I’m fine, Dad. Let’s sit outside, OK?” I headed out to the deck, desperate for air.

It had been almost a year since he’d found out that I’m HIV-positive. Feeling cowardly, I’d asked my mother to tell him. Before that, I’d tried a few times, calling and hanging up or rambling on about sports, hoping to find a crack in which to plant the seed. I even tried to visit him but got only as far as a rest stop on Interstate 65 outside of Chicago. I was stricken by fear, not so much of his disappointment at learning that his only son had contracted HIV, but that his response might make me see that it wasn’t a virus that was coming between us, but something far more pernicious: pride.

My father and I had been at war for as long as I could remember. I wanted him to be someone other than who he was, and he no doubt felt the same toward me. My father was a high-school baseball coach and later a principal. For years, I’d watched him guide teenagers through the maze of adolescence, yet I never took a word of his advice. I physically couldn’t. I would stand by his easy chair in the family room and listen, but his words were like pills that I gagged on or hid in my mouth only to spit out once he was gone. Even my own friends would come over to talk to him, which only drove me farther into angry isolation. To his credit, my father often tried to break through, but he had to fortify himself first with alcohol, and this proved disastrous. I couldn’t help but see him as a hypocrite — a man who could counsel and inspire hundreds of young men, but who couldn’t reach his own son.

The day after my mother told him the news, he called. His voice cracked, and I could hear him trying to pick up his words and hand them to me, one by one. “Are you all right?” he asked, over and over. It wasn’t so much what he said as what I heard in his voice: I heard somebody I’d never met before, a man he didn’t even know so well himself.

I’d suggested this visit in our first e-mail exchange. My father had finally gotten online after I’d convinced him that he’d enjoy writing letters to his old friends and to his grandchildren in college. He and I, though, hadn’t written to each other in years — not directly, anyway. He’d tack a line onto the letter my mother sent with the check on my birthday, or the occasional postcard from their yearly trip overseas. His one and only correspondence to me during the two years I was in West Africa in the Peace Corps came when I couldn’t make it home for my grandmother’s funeral. He mailed me a postcard of a cardinal sitting in an evergreen bush. He wrote with such force that his pen made raised letters, like Braille, on the opposite side.

So when he sent me that first e-mail, I wasn’t sure how to respond. I was ready for him to go on about our usual topics of conversation — the Cubs’ failures, Indiana basketball, how my car was running. But, to my surprise, he’d poured out an uncharacteristically effusive and personal ramble about his past: the story of being thrown in jail for sneaking a black teammate into a Georgia hotel room. That was back in his glory days, when his future held more than coaching high-school baseball in a farm town in northern Indiana.

I wrote back suggesting we take a trip to Wisconsin, where he used to play for the Milwaukee Braves’ farm club in Eau Claire. I knew it wouldn’t be easy to convince him to go, so I told him a story about wanting to write an article about his years in the minor leagues. We both knew it was something else forcing us back together, but we decided to call it baseball.

Now here he was in my apartment on the weekend of my fortieth birthday. After he’d settled in, we went out to dinner and talked about what I had in mind for the weekend.

“So we’re just going up there to see the ballpark?” he asked. “Is that it? You know how far it is up there? For Christ’s sake, we’ll be in the car the whole time.” He sighed and looked around for the waitress.

“Do you still want to go?” I asked, trying to hold back my anger, reminding myself that he was just tired after driving half the day.

“I about didn’t come. Walked around the house wondering if I should come or not. Sorry, I have to tell you that. . . . I don’t know what we’re doing, but I’m here now.”

“We’ll make it,” I said, speaking to myself as much as to him.

For the first hour, we drove through the rings of Chicago’s western suburbs. He toyed with the tape recorder, cursing it for not working. Still somewhat in shock that we were actually doing this, I kept thinking that something was going to happen to make us call it off: Car problems. Sickness. An act of God.

My father and I rarely spent time together, just the two of us. Even when I was a kid, I don’t remember many outings with no other family members present. He took me to the ’72 World Series in Cincinnati to watch the Reds play the A’s, and on a few disastrous fishing trips. But we’d never developed any real father-son camaraderie.

We’d tried, of course — perhaps too hard. In high school, I was a jock and loved sports, excelling in football and basketball. But baseball, his sport, the sport that had defined his life, defeated me no matter how hard I tried. I was convinced my failure was a curse, a punishment for something I’d done wrong. I wasn’t so bad in the field; I just couldn’t hit. Coming up to bat was a drama I dreaded as soon as I put on my uniform.

I remember each hit I got in Little League, all three of them: two bunts and a miraculous grounder up the middle that I hit with my eyes closed. Each inning, I prayed to be up first to get it over with. Making the first out was forgivable; making the last out made me sick to my stomach. I got used to hearing that great baseball lie “Remember, a walk is as good as a hit.”

Determined to make me a hitter, my father would take me out in the backyard and go over the basics again and again: “Level swing now. . . . Choke up. . . . The wrists, turn your wrists like I showed you. ‘It’s all in your wrists’ is what Ted Williams always said. . . . Keep your head in there, even stance.” Then he’d pitch a few. Despite my effort to concentrate on his instructions, my bat grew heavier and heavier with each swing through the evening air. The harder I tried, the more insistent he became: “Keep your eye on it now, God damn it! You’re not watching the ball.”

“I am too!” I’d yell back.

Then he’d explode, or I’d throw down my bat and stomp off into the house. He was sure I was doing badly just to piss him off. And maybe, subconsciously, I was.

Then, in high school, after he had long given up coaching and become the principal, I decided to go out for the school play rather than the baseball team. That night at the dinner table, he threw a fork, nearly hitting my mother. “That’s it,” he pronounced, as if he were God. “You’ll never play again!” And I never did.

In the past few years, I had invited him to Chicago a couple of times to see a Cubs game, but he’d always brought one of my nephews or my brother-in-law. We seldom even talked on the phone. When I’d call, he’d hand the phone to my mother, then listen in on the other line in the bedroom, waiting to say a few words just before we hung up: “What do you think of that Tiger Woods, huh?” Such meaningless phrases would echo in my head long after the call had ended.

“SHE TOLD ME PLAYING BALL WAS FRIVOLOUS.” My father’s amplified voice jumped out of the tape recorder, shattering the silence.

“There. It works,” he said, turning down the volume. “Some of those questions you sent me I already answered on the drive up.”

“ ‘Frivolous’?”

“My mother never thought much of my playing baseball. I don’t recall her ever coming to watch me play. Oh, she came down that first year, when I was playing in Georgia. But she always thought I was wasting my life. We weren’t allowed to play games in the house. We had no cards, God forbid. No radio or diversions. . . . Should I have the tape recorder on?”

“Yes,” I hissed. I’d been so entranced by his tone of voice, I’d forgotten that I was supposed to be getting all of this down.

My father was born in 1929 to a family of Scotch-Irish farmers who had settled in Blackford County, Indiana, after the Civil War. There, my great-grandfather had started a farm, naming it the Bull Skin for the bloated cattle carcasses that floated up periodically from the depths of a bog on the property; the poor creatures had gotten caught in the muck trying to cool themselves and couldn’t be pulled out.

The Depression took its toll on my forebears. The stories were legend and became more poignant each Christmas. My father would slip into the kitchen to keep his coffee cup warmed with vodka as he reminisced with my aunts and uncles about not having any presents or Christmas trees. Finally, my grandmother would angrily interject: “We were lucky to have something to eat! People starved, is all I remember.”

Yet the ultimate scar from the Depression was not scarcity; the real pain arose from my grandfather’s death. Perhaps it was because my father felt his absence more at Christmas that he became suddenly obsessed with the past. My grandfather, whose name I bear, didn’t survive the thirties. They say it was the anxiety of farming, my grandmother’s penchant for wearing the pants, the lingering memory of his first son’s death in World War I, and then, months later, his first wife’s. Whatever the reason, he voluntarily admitted himself to the state mental hospital in Richmond; then he came home, supposedly cured, and hanged himself in the garage. My grandmother, an evangelical Methodist who believed that work solved all of man’s miseries, raised my father by herself.

So it came as no surprise when he described to me how, when he was a boy, he took refuge in his imagination and sports (as I did): “I never stayed around the house. If there wasn’t anyone to play with, I threw an old rubber ball against the back porch, making believe I was the pitcher, batter, and fielder all in one.”

“Didn’t you ever play catch with your dad?”

“No. He was . . . unavailable, when he wasn’t in the hospital. He was preoccupied.”

“His illness?”

“Yes, yes. He was there, but he wasn’t. . . . You know?”

He paused. I knew where the conversation had to go, and so did he. His father’s suicide was a subject he didn’t care to elaborate on; he felt people — especially me — made too much of it.

I had written a poem about my grandfather’s suicide years before. My father was shocked by the imagined version I’d pieced together from overheard fragments and his vague stories. Seeing it in print troubled him. He said almost nothing to me about the poem, but I could see in his face that I had entered into some private place where he’d been certain nobody could find him.

Looking at the few pictures that we had of my grandfather, I often unconsciously picked him out of the crowd of ancestral faces. Severe and anxious, his thin, Celtic face and hollow eyes haunted me. On visits to my grandmother’s, I would always find some excuse to go out to the garage and dare myself to glance up at the rafter that had held the rope he’d placed around his neck.

My grandfather’s mysterious suicide became a kind of totemic memory for everyone in my family, a dark side to life that could not be ignored. I’d sometimes used it to impress those whom I wanted to take me seriously, as if it gave me some sort of existential currency. Little did I know then how those images of my grandfather’s death would return to me one spring day when a Hispanic social worker handed me the results of my HIV test, looked sullenly at me, and asked, “You didn’t expect this, did you?”

Now I sat beside my father, listening to him recount that awful day when he came home from grammar school to find his father’s boots dangling in the air next to an overturned stepladder. I wondered if I had the guts to tell him how close I had come to following in my grandfather’s footsteps. He turned off the tape recorder and stared out at the cornfields along the interstate. “After finding my dad, I ran into the house, called my mom, who was out at the farm, and told her. Then I waited there in the dining room, looking out that window, up Franklin Street. . . . I don’t know how long I waited; maybe a half-hour. Mom finally showed up, and then your Aunt Martha came home from school. I don’t remember much after that.”

“Did other people know? Your friends? Your teachers?”

“I don’t know. I suppose they did. Some of the neighbors looked after me. I think they thought I was a brave little kid: you know, calling for my mom, waiting alone, and . . .”

“Finding him?”

“Yes.”

My father’s mouth clamped shut, and his neck muscles tightened in an effort to keep hold of his emotions. His whole life seemed locked behind his jaw. I wanted to touch him, put my finger on the taut skin of his neck, relieve him somehow. I’d thought that, by talking about my grandfather’s suicide, I could somehow explain to my father those spells of self-destruction that landed me in the apartments of unknown men at 4:30 in the morning, searching for my clothes, still trying to appease a hunger I couldn’t satisfy. Instead, for the first time in my life, I felt the pain my father must have suffered over his father’s suicide. In his slumping shoulders and rigid stare, I saw, not a sixty-eight-year-old man, but a fatherless boy of ten.

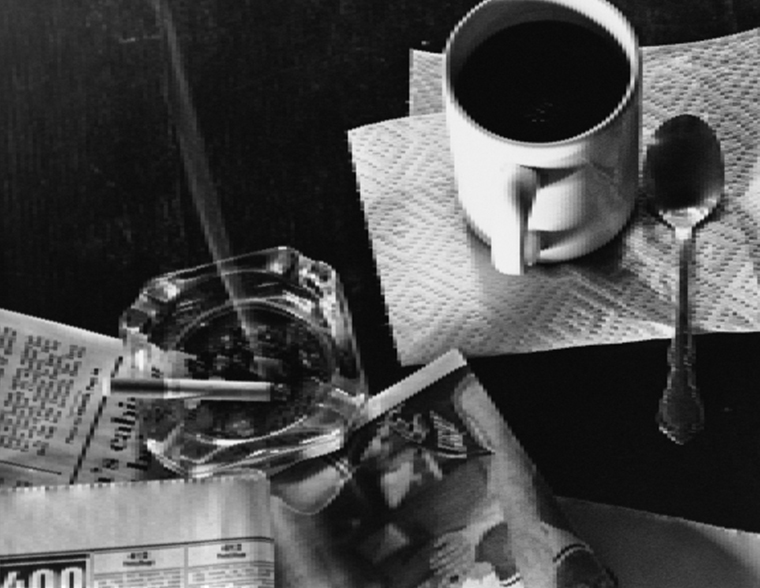

We needed out of the car, so we pulled into one of those ubiquitous interstate restaurants that serve grits and gravy and make middle-aged waitresses wear bonnets. Over coffee, my father launched into the stories he wanted me to hear and write about. I’d left the tape recorder in the car, but it didn’t really matter.

“I was only nineteen,” he began, telling the story of how he’d been asked to sign with the Yankees but had declined, because his mother wanted him to stay in college.

I’d heard this story many times before, but now I pressed him for details. “Why didn’t you sign? It was the Yankees.”

“I didn’t know what I was turning down. . . . I didn’t know anything.” He shook his head. “Mom got the town judge to come over and convince me to finish college. He was a friend of the family. I didn’t have a father.” He said this last part as if he’d somehow forgotten it. “So I sent the train ticket and the contract back.” He ate a few bites, and, as he chewed, I wondered how his life would have been different if he had signed.

“You know who was on that Yankees farm team in Joplin, don’t you?” he asked.

“Not Mickey Mantle?”

“Yep. His first year in the minors.”

“You would have played with Mickey Mantle?”

He nodded and went back to mopping up his gravy with his biscuit.

After he’d finished college, the Cardinals had asked him to try out at one of their camps in Ohio. And then, as the Korean War was heating up, the Cubs sent him a ticket to Chicago.

“They did it just to impress me,” he continued, back in the car. “It was part of the way clubs got kids to sign minor-league contracts. They put you up downtown in a fancy hotel, came to get you in a cab, and took you over to Wrigley.”

“So what happened?”

“Oh, I put on the uniform and everything. They were playing the Brooklyn Dodgers that day: Jackie Robinson, Pee Wee Reese. Before the game, I got to go out and take batting practice with the team. The only problem was, I hadn’t brought my bat.”

“They didn’t have any bats? A major-league team?”

“Back then, a player had his own set of bats he took with him, like a golfer has his clubs.”

“Why didn’t some of the players let you borrow theirs?”

“Are you kidding me? They weren’t going to let some kid borrow their bat!”

“But why?”

“Because, God damn it, they didn’t want anybody to take their job away from them! They weren’t gonna help me look good. Ol’ Chuck Connors — remember him, from The Rifleman? — he played first for the Cubs. He wasn’t about to lend me his bat. Finally, big Hank Sauer, the left fielder, who was about six feet, six inches, came over and handed me his bat: a great big log of a bat, four inches longer than any I’d ever swung. But I choked up and got up there and hit line drive after line drive. A couple even bounced off the ivy on the right-field wall. Then they asked me to dress and go upstairs to the office, where they offered me a class-A contract for Des Moines.”

“And you didn’t take it, right?”

He chuckled at his cockiness and shook his head. “I thought I could do better. But the Korean War was on, and I got called up like everybody else.”

He seemed a little tired of telling tales of his youthful hubris. I jumped ahead and asked him about the minor-league contract he finally got with the Milwaukee Braves, after he’d returned from the service in Germany. But the silence that we’d been fighting off all day opened up once again, pulling us toward the subject we’d spent so many years avoiding. I could tell he wanted to get it over with. I stared straight ahead, searching for a question he could chew on. But he beat me to it.

“So, what about you?” he began. “Didn’t I come so we could talk about you?”

“Yeah, I guess. . . . I’d hoped so.”

“I’m glad I came. Really glad. I wasn’t going to.”

“I know. You told me.”

“But I’m glad I did.”

“I’m glad, too.”

My tongue became thick again, and I recalled long afternoons sitting silently beside him in a bass boat or driving home in our station wagon from Little League games: times he tried so hard to be my father; times I tried so hard to be his son.

“You’re feeling OK?” he asked.

Talking about how I felt was as close as we ever got to talking about my illness and what had caused it. We could discuss AIDS in Africa, or some new treatment he’d read about, but not my private life.

“It’s not as bad as it was,” I replied.

“You got to keep your spirits up.”

I felt my stomach knot at the thought of how far we were from really talking about what had happened. My parents had no idea how close I’d come to dying, either from this virus or by my own hand.

“You do the yoga thing, and the swimming, and all the exercise — that helps, doesn’t it?”

“Yeah.”

“That’s good.”

“I know it’s good.” The muscles in my face were contracting, as if I were in a cave, pinched between rocks, my breath growing short from lack of air.

“You shouldn’t get depressed, you know. That’s the worst thing. They say it makes you more —”

“I know, Dad,” I cut him off. “I read the articles, too.” I wasn’t sure what I wanted him to say, but I knew I couldn’t accept his advice. Silence buried us again.

He finally blurted out, “Well, I hope you don’t think it’s anything I’ve done.”

I could tell this was what he’d been wanting to say ever since my mother had told him. I paused and took a deep breath. I wanted to reply, Of course it’s your fault. You could have asked me anytime over the past twenty-five years, “What’s wrong?” I wanted to say, It’s everyone’s fault. Why didn’t anyone stop me from walking off that cliff? But self-pity and anger only rob us of the wisdom learned through suffering. And besides, I was just too tired to hang on to them anymore.

“No,” I told him, “it’s not anyone’s fault.”

“I think it’s just biological, like they say: DNA, you know?”

I chuckled quietly, derisively. It seemed an absurd thing to say, or maybe I was just uncomfortable hearing my father simplify something I’d spent all my adult life trying to understand. “I think it’s a little more complicated than that.”

“Maybe so. . . . I’m still confused about you and, and . . . everything,” he said, loading all the mysteries of sexuality into that last word.

“So am I. I’m attracted to men and women, and I’ve always been like this.”

“I see.” He looked pained, but not necessarily over what I’d told him. It seemed as if our conversation had triggered a memory of some other, greater disappointment.

I, on the other hand, felt liberated. The words had come to me as if wrapped in a box with my name on it. I’d finally said it, something to explain who I was. Feeling a surge of courage, I plowed ahead: “For a long time I kept thinking it would just go away, or I would get married.”

“Yes, your mother and I —”

“I guess I was ashamed. It was a long time before I could tell even my closest friends. I should have told you, but . . .”

“Yes.” His voice sounded old and sad. There would be no catharsis, no dramatic, tearful scene.

I looked out the window at the rolling hills of Wisconsin’s farmland. There was so much I wanted to say, not just to him but to all he represented. But the explanations I’d crafted seemed pointless now. He was just my father, a man nearing seventy, as vulnerable to life’s vicissitudes and absurdities as I. How had he managed his disappointments and failures all these years? How did anyone? At forty, I marveled at those older than I who hadn’t wrapped themselves in the shroud of bitterness: how heroic to continue on despite failing to live up to our own aspirations.

Scanning the afternoon haze, I wondered how the rural landscape of Middle America, once the source of my understanding about the world, had lost its grandeur for me. I’d always identified with its anomalies: the solitary sycamores that defied the uniform rows of grain; the groves of oak atop the mild plateaus; the bogs too wet to till; the boulders and odd-shaped mounds, remnants of the migrating glaciers. Those spaces, no matter how denuded and enslaved by profit and progress, had always been my refuge when my blood began to burst.

My father and I continued on our way, speaking but not speaking. The tension was easing, and he was eager to offer himself to me through words, to give me something to take away from our weekend. He kept mentioning my friends, wondering what we did together on weekends, where we went, coming closer than ever before to asking about that part of me he’d never known much about: my private life.

Before returning to Chicago, my father and I would visit an old friend of the family, a woman whose grandson had died two years before of AIDS. He, too, had been a coach’s son. She served us Jell-O and ham sandwiches, and as she watched us eat, she began to talk about her grandson as if he were somewhere in her house, pointing to a back room where he’d stayed while in college, and out the window to the park where he used to study under the tall pines — and also where, I remembered my mother telling me, they had spread his ashes.

It was early evening when we finally arrived in Eau Claire, at the city ballpark where my father’s career had reached its peak two years before I was born. Carson Park was hidden in a grove of old pine trees in an oxbow of the Eau Claire River, not far from a faded downtown long ago fallen victim to the malls out on the highway.

A bronze bust of a man with a bat on his shoulders met fans as they climbed the steps from the parking lot. “Hank Aaron,” my father announced proudly. “He hit his first home run in organized ball right here.”

“Did you meet him?”

“No, he left the year I came.”

I’d been hoping we would come upon a minor-league game in progress, but Milwaukee’s class-C farm club, the Cavaliers, were out of town for the all-star break. In their place were some teenage boys, an American Legion team, warming up in the outfield. I followed my father around as he surveyed what had changed, pointing out the new dimensions of the outfield, where the dugouts used to be. Then he walked onto the field to introduce himself to the Legion coach. I could see my father puffing up, hear him announce that he used to play here. He was in his element.

They talked about baseball and the old Northern League, made up of teams from cities like Winnipeg and Wausau, Saint Cloud and Fargo. I looked over at first base, where for two seasons my father had tried to impress the Milwaukee scouts in their fedoras, to show them that he could make it in the big leagues.

The Legion players jogged over to their dugout, all gangly, innocent arms and legs. The other team took the field, trying hard to look the part of men, but practically skipping out to their positions. I remembered being their age and one of those very few moments in a baseball uniform when I wasn’t embarrassed to be the coach’s son who couldn’t hit:

I am in Pony League, batting against a pitcher who has probably struck me out twenty times since Little League. I hear someone in the stands yell out, “Choke up in there and get a hit!” It sounds like my father, but then, every time I come up to bat I hear his voice, whether he’s there or not.

Miraculously, the pitcher throws the only pitch that I can get my bat on — low and outside — and I send it over the right-center fence. Or at least that’s what everyone tells me. I never see it, never even feel the bat hit the ball. All I see, as I run toward first, is my manager bouncing up and down with his brown belly flopping out of his T-shirt and his arms winding around like a puppet, signaling, Run! Which I do, like a good coach’s son, rounding first and then slowing to a trot, seized by the fear that I might not tag each base.

I return to home plate and am bombarded by my teammates, who slap me with their gloves and hit me the way fifteen-year-olds do, terrified to touch but wanting to show affection. And then I glance over at the stands. There, past the empty three-tiered bleachers and the usual clutch of mothers in lawn chairs, in his white shirt and tie and his black wingtips, one foot on the front fender of our green Ford station wagon, is my father. He was there all along.

When the Legion game started, my father joined me in the stands, and we watched the first inning. The coach in him quickly sized up the players’ strengths and weaknesses, but it was getting late, and we needed to find a hotel. He folded his arms and looked out at the flagpole flying the American flag in dead center field. “We might as well get out of here,” he said. “I’ve seen all I want to see.”

Back in the hotel room, he stripped to his boxers and lay in bed with a can of beer, reading USA Today and listening to CNN’s sports highlights. I tried to play the part of the writer, jotting down whatever fragments came to mind: Chicago Cubs. Mickey Mantle. DNA. My father looking out the dining-room window, waiting for his mother.

He peered over his dime-store reading glasses at the TV, the bones in his legs thinly veiled by skin (just like mine). I recalled seeing him in a hospital bed in Fort Wayne when I was not yet five. He lay there, immobile on the white sheets, no longer the towering figure I cowered before in our tiny ranch house. A cast swallowed his leg to his groin, leaving only his toes and his penis hanging out. He was sleeping. My mother told my sister and me that he had been in a wreck. My sister gave him a get-well card. We didn’t stay long.

I’d never really understood what that accident had meant for my father until he told me the full story on this trip: It was 1961, and my father’s chances of making it into the Majors were waning. He left Eau Claire and got a job teaching and coaching in Indiana. Yet he continued to play semipro ball in Fort Wayne. One spring night, his reluctance to give up on his baseball career brought him and a friend to Ohio to convince an old teammate and retired Red Sox pitcher to join a new team they were putting together. But the pitcher refused, and so my father and his friend drank their way back home until they ran their car off the highway, nearly killing themselves. My father’s dream of becoming a major-league ballplayer was finally over.

My father and I left Eau Claire for Wausau the next day, to visit another ballpark where he had played. Being behind the wheel seemed to calm him, and he began to talk of his old teammates and his theories on hitting. He became philosophical, and his voice sounded soothing and, at times, even lyrical. I found myself nodding off, but he didn’t mind. Occasionally I opened my eyes and looked out at the swells of green pasture and the square lots of trees.

When he fell silent, I wondered what other questions I might ask, but the silence had a power all its own, and I felt to break it would interrupt his memory. Instead, I lay back and tried to remember seeing him play. I was barely three years old when he retired, but I have an image of night games at a ballpark in Fort Wayne. I’m not sure I even remember him batting or running or playing first base, but I can remember the lights, the giant poles growing up out of the ground on either side of the field, rows of bright bulbs on top pouring out light, pushing the darkness back into the trees. It was as if the night had been opened for these men in uniforms to perform this ritual called baseball, this game they loved so much.