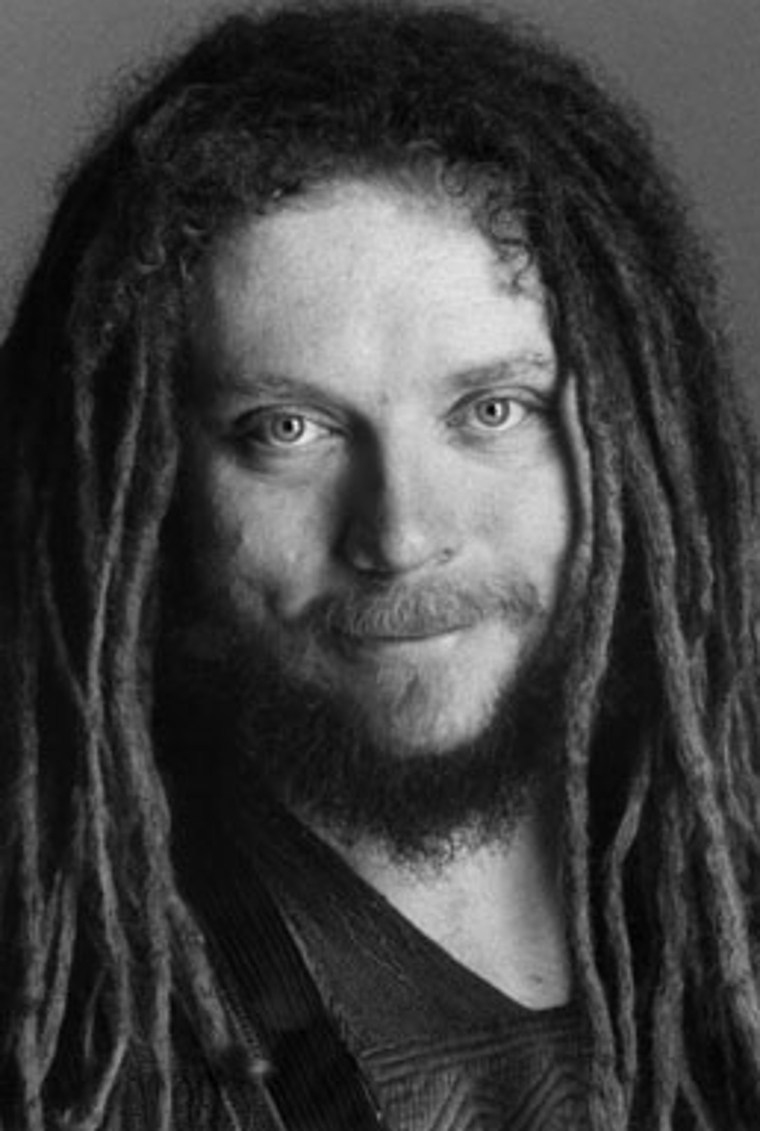

Computer scientist. Software engineer. Visual artist. Writer. Musician.

Forty-four-year-old virtual-reality pioneer Jaron Lanier has somehow managed to integrate these pursuits into a coherent whole. Whether he’s plucking the strings of an ancient Indian sitar or writing code for a computer program to assist surgeons, Lanier is using what he calls “humanistic technology.”

Lanier grew up in Mesilla, New Mexico, the son of bohemian parents. His father was, at times, an architect, a Macy’s window designer, a schoolteacher, a science writer, and the on-air sidekick of Long John Nebel, host of the first call-in radio talk show. Lanier’s mother, a Holocaust survivor who died when Lanier was just nine years old, was a child-prodigy pianist and artist.

A child prodigy himself, Lanier led an insular existence in southern New Mexico, which he remembers as “an extraordinarily backward, macho, violent, dangerous, illiterate place.” Despite being one of the poorest areas of the country, it also had one of the highest densities of technical PhDs in the world due to the government weapons-development programs that were based there. Lanier found a host of scientists and engineers to interact with and enrolled in college by age fourteen.

Before he graduated, Lanier transferred to an upstate-New York art school whose name he won’t mention. He hated the elite atmosphere at the school and ended up flunking out. (He has never completed college.) He dabbled in the avant-garde music scene in Manhattan before returning to New Mexico, where he spent a year organizing protests against the burgeoning nuclear-power industry. To make money, he herded goats and worked as an assistant to a midwife who served poor Mexican farmworkers.

Lanier moved to Silicon Valley in the early eighties, at the start of the personal-computer revolution. He began programming computer games, turning his home into a makeshift workshop. His incessant tinkering resulted in the technology known as “virtual reality,” or “VR,” for short. In 1984 Scientific American put him on its cover. Because the magazine required any featured scientist to be affiliated with a research institution, Lanier created one of his own on the spot, calling it “VPL Research.” It lasted for fourteen years, but ultimately collapsed.

Not so with Lanier’s interest in VR. In 2000, as the lead scientist of the National Tele-Immersion Initiative, he and his colleagues demonstrated a new technology that allows individuals in remote locations to view each other in three dimensions by wearing special goggles. “Virtual reality is precisely a way of thinking about computers that puts humans and human experience at the center,” says Lanier.

Lanier continues to compose chamber and orchestral music and has performed with such artists as Philip Glass, George Clinton, Vernon Reid, and Sean Lennon. He also collects unusual musical instruments, and some thirteen hundred of them are on display in his home, including the world’s biggest flute and a stringed instrument made from pieces of beds thrown out by an old hotel in Baltimore. Currently he is collaborating with playwright Kai Hong on an opera about Jewish refugees from Stalinist Russia who found their way to Korea. Lanier also writes on high-tech topics, Internet politics, and the future of humanism. He has appeared on the NewsHour and Nightline and gives lectures around the world.

Despite his accomplishments, Lanier in person is warm, easygoing, and free of pretense. Whatever subject he’s discussing, he maintains his sense of humor and an almost childlike playfulness. As we spoke in his living room high up in the Berkeley hills, a toy giant squid dropped onto my shoulder. At that moment, we were discussing his essay “One Half of a Manifesto,” which challenges the notion that computers will one day surpass human intelligence. “Let the record reflect that a toy giant squid interrupted the natural movement of the interviewer’s head,” Lanier said.

JARON LANIER

Cooper: Why do you think virtual reality hasn’t become as popular as you might have imagined?

Lanier: In 1983 I predicted it might start to become popular around 2010. That prediction was based on a number of things: trends in computer power and material science, and also how long it would take to write the software. [Laughter.] My feeling is that it’s easily on track for 2010 in the hardware department. For software, maybe not.

Cooper: How will the average person use it, in your view?

Lanier: The natural application of virtual reality is not as a successor to the video game or the personal computer or the television, but as a successor to the telephone. Its natural use would be as a means of contact between people.

Cooper: Isn’t that what the tele-immersion project was about?

Lanier: The goal was to bring a realistic human presence to VR, so that when you looked at the other person, instead of seeing a puppet-like figure, you’d see something that looked more like a real human being. It turns out that the puppet-like figure itself is rather profound, because it reflects the body language of people. One’s unconscious body motions are far more important in communication than we had previously realized. A puppet figure actually can be a wonderfully intimate form of connection. My sense is that the ultimate form will be one in which people’s faces are rendered realistically, but not other parts of their bodies.

I’m worried that the technologies of the future will be created by people I call “cybernetic totalists.” . . . They believe there isn’t any real difference between people and computers, that the human brain is just a better computer than the ones you can currently buy from Apple or Dell.

Cooper: What are the dangers of putting ourselves into these virtual worlds? Is there an addiction factor, as with a drug?

Lanier: That’s a question that I’ve been hearing since the very dawn of VR. Let me answer it first, and then I’ll tell you some of the history behind it. The answer, so far as I can tell, is that a fully realized virtual-reality system would be almost the direct opposite of a drug. VR maintains its illusion through the user’s own effort. Head motion is very important. In fact, if you were able to put your head in a vise and hold your eye muscles still, so that you were not interacting with your environment at all, you’d lose the ability to perceive the room you were in, and it would gradually disappear. I don’t recommend you try this at home, however.

The experience of using a good VR system is more like riding a bike: You get tired after a while. It involves effort. It’s not a passive experience.

The other factor is the software. It’s simply impossible to build enough content to make a virtual world of any interest, even with computers doing the work, or teams of artists, or cheap Third World labor.

Cooper: I’m surprised to hear you say that.

Lanier: The only way to make a virtual world worth being in would be through collective crafting by the entire user community. It’s not like a movie, which has to look good from only one angle. And virtual worlds made automatically by computers aren’t interesting. We’ve made a virtual-reality program that assists heart surgeons, but many people worked for at least a decade to build that one simulation. It’s very labor-intensive to build virtual worlds.

One more thing about virtual reality — I don’t know how to put this exactly, it’s just so obvious — is that it’s a waking-state experience: if you close your eyes, it goes away. It’s also outside your body. It’s a communication technology; it’s not mucking with your brain the way a drug does.

Cooper: So what is the history behind the drug question?

Lanier: In the eighties I met Timothy Leary at the Esalen Institute in California, where he was teaching a workshop. He said: “I hate this workshop. The students are dull. I need to get out of here, but I’m under contract.” So he came up with this scheme where a double — who actually didn’t look much like him — took over the workshop, and I sneaked him out under some clothes in the back seat of my car. When we drove past the guard at the gate, it was like escaping out of East Berlin or something. I brought him to a friend’s house in Big Sur. Tim was a jolly guy, and I really enjoyed meeting him. He made his living on the lecture circuit at that time, and he needed some new material. When I told him about virtual reality, he said, “Great! I’ll start talking about it.”

I begged him not to do it, but he liked to cause trouble. His motto was “Let’s upset the parents.” I got him to tone down the message a bit, but soon there was a headline in the Wall Street Journal that talked about “electronic LSD.” The article practically accused me of being a drug user. That’s how the notion that drugs and VR might be similar came about.

Cooper: What about people using VR together with drugs?

Lanier: I have to say, it doesn’t make sense. Taking a drug while in virtual reality would be like putting gasoline in your bicycle; it’s just stupid.

I’ll tell you how drugs and virtual reality could connect: There’s a burgeoning field of virtual-reality therapy. Some therapists use VR for phobia desensitization. Others use it to document certain psychotic delusions. I could imagine a therapy in the future combining psychiatric drugs with virtual worlds. I am not an expert on this, though. I tend to be skeptical of both types of treatments.

Cooper: What’s behind your fascination with cephalopods: squids, octopuses, and the like?

Lanier: They’re an obsession of mine because they’ve evolved into something that’s a little like virtual reality. Some of the fancier species can animate their skin and also change their body shape very dramatically. They can communicate with body morphing and animation patterns. They’re just gorgeous.

Cooper: So virtual reality could allow us to communicate in much the same way?

Lanier: Yes, in virtual reality we could change the shape and color of our bodies — or, rather, the computerized representations of our bodies. In the real world we have to use symbolic references to communicate certain ideas, but in the virtual world we can just become them. So one can think of virtual reality as making people more like cephalopods.

Cooper: Have you spent much time around cephalopods?

Lanier: I have befriended cephalopod researchers and gone along on some research trips now and then. Some of the more complex cephalopods have all the makings of a dominant species. They have this tentacle-eye coordination that’s, in a way, more impressive than our hand-eye coordination. They have wonderful brains and sensory systems. They’re really bright. What they lack is a childhood. They’re abandoned by their parents at birth. Without childhoods, without nurturing, they can’t develop cultures. They don’t have any accumulated wisdom. They have to start fresh with each new life, and they do amazingly well with it. But if they had childhoods, I’m sure they’d be running the planet.

Cooper: How does music fit into your life?

Lanier: A lot of people who like math or science also like music. In my case, I think I grew up believing that to impress one’s parents one must be good in both science and music.

Cooper: How did you become interested in exotic instruments?

Lanier: I don’t think of them as exotic, really. They’re all made by people. I guess the first nonstandard instrument I had access to was my mother’s old zither, which she managed to bring over from Austria. I used to get all kinds of strange sounds from it. After that I somehow came across a shakuhachi, which is a Japanese flute. I learned to play it and eventually studied it in Japan. I’ve been tracking down new instruments from various corners of the earth ever since.

I think of an instrument as being like an actor’s mask: After you put on a mask, you’re still the same person, but somehow a new aspect of you comes out. Each instrument isolates and helps focus one aspect of you, a new character.

I also think of instruments as cultural time machines: If you’re interested in what it was like to be in Europe three hundred years ago, you should play a three-hundred-year-old instrument. You have to learn to hold your body and move and breathe like the people of that time. It’s a unique way of entering their world.

Another thing that fascinates me about instruments is that they are always on the leading edge of technology. There’s this idea that the latest technologies get developed by the military and then trickle down to the rest of us, but I don’t find that to be supported by historical facts. So far as I can tell, musical instruments, not weapons, have been the leading edge.

Cooper: For example?

Lanier: The oldest known human-made artifact is the Neanderthal flute. There’s some debate about whether the musical bow or the bow and arrow came about first. Of course, there’s no way to know definitively, but I think the musical bow came first. Archaeologists have found some pseudobows — a stick with a piece of bark that’s lifted up, so it becomes like a string — that seem to be very old. I think that people were driven initially by the sound the bow made. I think most weapons are the indecent offspring of musical instruments. Another good example is guns. Initially, the Chinese were trying to figure out how to cast bigger and bigger bells when one of those got turned sideways and became a cannon, and eventually the gun.

It’s not just weapons. The computer can trace its origins to an instrument. It’s thought that the Jacquard loom, a fabric-design-and-production machine, was the inspiration for Babbage’s calculators, but the Jacquard loom itself was inspired by automatic music-reproducing machines, player pianos that were able to create music from mechanisms. Hewlett-Packard was originally formed to make a music synthesizer for Walt Disney. [Laughter.] So one of the highest technological priorities in history has been people’s attempts to communicate with each other by making peculiar sounds. I find this endearing; it’s a much more positive framework than the weapons framework.

Cooper: You use the phrase “circle of empathy” a lot. What does it mean?

Lanier: I’ve been using that term for a long time. Peter Singer, the Princeton animal-rights activist and philosopher, uses it as well. It’s the notion that you draw a circle around yourself, and within the circle is everything you have empathy for. Outside the circle is everything you are willing to compromise on. One way to decide what’s in and what’s out is to base the decision on consciousness: conscious beings are inside the circle.

Cooper: Who’s inside your circle of empathy?

Lanier: That’s a really hard question. I think it would require superhuman wisdom to choose correctly, and we all have to make do with our frail human resources. The way I’ve dealt with the question of which animals to put inside the circle, for example, is just to spend some time around each species and decide how I feel. I didn’t know what else to do.

Cooper: So who’s in and who’s out?

Lanier: Well, I won’t eat cephalopods. [Laughter.] I was served squid sushi in Korea recently, and I couldn’t deal with that. But I’m not on a crusade to make other people stop eating cephalopods.

One problem we humans have is we tend to draw a sharp line at the edge of our circle, and we battle over whether an embryo should be inside the circle of empathy, or a severely retarded child, or stem cells. I think we should have a sort of demilitarized zone where some things reside. We need to accept that there are people who have very strong feelings that differ from ours, and we have to find a way to coexist, even if it’s painful.

Cooper: Do you think computers should be inside our circle of empathy?

Lanier: My answer is an emphatic no, but I’m in the extreme minority on this within the computer-science world. My sense is that most physicists and biologists would put the computer outside the circle. Computer scientists, however, tend to believe that the computer will eventually go inside the circle, or perhaps should already be inside it.

If these were merely their own personal beliefs, it wouldn’t matter — all of us have different beliefs, and that’s a good thing. The computer scientists, however, are in a special position of power because they design the machines that we end up using to communicate with one another and to manage our collective memories. So their ideas have an extraordinary influence on the rest of us.

I could compromise and put computers in the demilitarized zone if the computer scientists felt strongly about it, because I have to give them that respect. But computers are not being proposed for some sort of gray zone. The rhetoric of today asserts absolute equivalence of computing and reality. Computers aren’t just in the circle. Computers are at the center of the circle — they’re more real than we are.

Cooper: You’ve written a controversial essay, “One Half of a Manifesto,” that challenges this idea about the primacy of computers. Why is it such a concern for you?

Lanier: I’m concerned that ideas about the nature of personhood and the meaning of life — the big ideas that are usually addressed by philosophy or religion or the arts — have already been answered in a computer-centric way by the preponderance of people in high-tech fields, and that their answers will be spread through the tools that they design and we use. If the tool you use to express your ideas has certain ideas embedded in it, then it’s very hard to escape those ideas; they’re implicit in what you do when you use the tool. As more and more human communication and financial transactions and teaching and expression take place through the digital world, structures that are built into this world will affect the nature of human experience. Over time this could create a problematic way of thinking about the self.

Usually, intellectual movements start out as written ideas that later become practice. For instance, Marx wrote his famous manifesto before there was a Marxist regime. Freud wrote his theories down before there were thousands of psychoanalysts. But in the world of high tech, computer programmers transmit ideas from their heads to the culture through the tools they design. For example, the creators of the original Internet, which was called the Arpanet, were supposed to build a tough system that would allow for government communication in case of an attack. But they were all starry-eyed idealists with a very American sensibility, and they conceived of the Internet as something with no central authority. Had their original code been even slightly different, the World Wide Web as we know it — a place where vast numbers of people have equal ability to consume or create — might never have happened.

The Internet is an example of good ideas being embedded in technology. But we’re not always so lucky. Sometimes the people who design software are too optimistic about human nature. For example, e-mail was invented by people who didn’t have sufficient paranoia about the dark side of human nature. Thus we have spam, fake addresses of origin, and so on.

Once you set up any computer program in a certain way, other layers of code get plastered down on top of it, and it becomes very, very hard to undo. I’m worried that the technologies of the future will be created by people I call “cybernetic totalists.” They are the dominant cultural force in computing and some other sciences, and they believe there isn’t any real difference between people and computers, that the human brain is just a better computer than the ones you can currently buy from Apple or Dell.

A key belief of cybernetic totalism is that there’s no difference between experience and information; that is, everything can be reduced to “bits.” When you don’t believe in experience anymore, you become desensitized to the subjective quality of life.

Cooper: What’s the reasoning behind their theory?

Lanier: Before I go any further, I want to emphasize that I have no personal enmity toward these people. For the most part, I’ve been able to maintain friendships with them. I hope that we will continue to demonstrate that it is possible to have friendships across ideological lines.

A key belief of cybernetic totalism is that there’s no difference between experience and information; that is, everything can be reduced to “bits.” When you don’t believe in experience anymore, you become desensitized to the subjective quality of life. And this has a huge impact on ethics, religion, and spirituality, because now the center of everything isn’t human life or God, but the biggest possible computer. You have this cultlike anticipation of computers big enough to house consciousness and thus grant possible immortality.

Another tenet of cybernetic totalism is the belief in Moore’s Law, which has held true so far and will presumably hold true for some time. Moore’s Law says that computers will keep on getting better, faster, cheaper, and more capacious at an exponential rate. And since the cybernetic totalists believe that the only difference between a computer and your brain is that your brain is faster and more capacious, they predict that computers will eventually turn into brains, and then surpass brains. More than that, they predict that this exponential change in computational speed and miniaturization is leading toward a “singularity”: at some point, the rate of improvement in computers will become so fast that people won’t even be able to perceive it. In the blink of an eye, computers will become godlike and transcend human understanding. Artificial life will inherit the earth.

Cooper: When do they foresee this occurring?

Lanier: A lot of computer scientists predict it might happen around 2020 or 2030. In order to believe this, you have to believe not only that Moore’s Law can hold true for that long — which I view as possible, though unlikely — but, more importantly, that computation quality will automatically follow computation quantity. For instance, you have to believe a superbig, superfast machine will automatically become super-intelligent. Cybernetic totalists invoke the metaphor of evolution to explain how quality will instantly come about. But what would have taken billions of years of natural selection will take place in the blink of an eye.

There are some among them who feel that the Internet as a whole is already alive. But most do not believe that anything resembling a human brain has appeared within the world of digital gadgets — yet. In their view, however, even if today’s computers aren’t the equivalent of a person, some computer fairly soon will be. Since they’re already living in that future world in their heads, they tend to design software today to reflect that imagined destination of tomorrow. That software encourages us to see the computer as a friend or a partner, an entity that we talk to and treat as an equal, instead of as a tool.

I find this philosophy of life to be very shallow, nerdy, dull, and antihuman, and it’s being spread to other people who are using the software developed in this narrow scientific community.

Cooper: Can you give an example of how using software spreads these ideas?

Lanier: Some time ago Microsoft hired a friend of mine to bring “artificial intelligence” into Microsoft Word. Among other things, my friend was partly responsible for the “auto-retype” feature of the word-processing program: as you’re typing, if you make a certain combination of keystrokes, Microsoft Word decides what it thinks you wanted to type and writes that instead. Now, I don’t want to claim that this is some enormous cataclysmic development. The world will survive auto-retyping. But I think there are some profound issues embedded in it. The auto-retype feature in Microsoft Word doesn’t make typing easier. Rather, it creates the illusion that we are stupid and the computer is smart. The problem is that the user has to learn a complicated set of keystrokes to get the desired effect, and the only justification for this is to make this software designer’s AI fantasy come true.

Another example of this is the credit-rating system, which is supposed to reduce risks for lending institutions and other financial-services companies. But it has never demonstrated any real ability to reduce risks. Credit-rating systems predict outcomes to some degree, but as reliance on them has increased, so have bankruptcy rates. So even though the ratings can be said to work in a limited capacity, they have failed the larger test. Yet people bend over backward to borrow money when they don’t need it, because they want to be favorably categorized by the system. Once again, we act stupid to make the computer seem smart.

A publicized example of computers appearing to be smarter than humans was when an IBM computer named Deep Blue was said to have beaten chess champion Gary Kasparov in 1997. The problem with this is that whenever you say that an artificial-intelligence program has achieved something that previously only humans could do, you inevitably redefine that achievement, making it less human than it used to be. In this case, chess was redefined as being about nothing but the moves. Typically there are all these mind games involved in a world-championship chess match. It’s a deeply human contest of subtle, nonverbal communication. That entire aspect of chess ceased to exist in the match with the IBM machine. They took a complex human experience and turned it into nothing but bits of information. Chess was turned from a full-on human encounter into something banal. If chess is about nothing but the moves, why have chess championships?

Cooper: You’ve said that a machine we call “intelligent” could just be a machine with an inscrutable interface. How so?

Lanier: If you talk to somebody who’s highly intelligent, he or she might say something that you don’t initially understand. Some of the most brilliant people say things that are a little bit beyond all of us. Similarly, the work of some artistic geniuses is hard to understand.

When a bad user interface, like the auto-retyping function in Microsoft Word, is labeled “intelligent,” some people could think it’s like a valuable abstract painting: hard to understand because it’s so ingenious. The more the program fails to make sense, the more they might think, Wow, this must be very smart. I think most successful artificial-intelligence experiments essentially have that character: people confuse inscrutability with a brilliance that’s beyond them. The irony is that a computer you can’t communicate with ceases to be useful as a tool.

Cooper: What else, besides the software, is promoting the idea of artificial intelligence?

Lanier: The idea has become very mainstream. A good example would be the Matrix movies, which dramatize the singularity scenario: a big computer becomes smart enough to take over reality, and humanity is housed in a simulation the computer runs for its own purposes. But it’s not just a theme in fiction. There’s a constant stream of artificial-intelligence stories in mainstream news sources.

In fact, let’s just see what’s on CNN’s website today. The lead technology headline is “Device To Save Hospitals Billions.” The story is about computers in hospitals that can automatically distribute the right amount of drugs to a patient. Let me read the first line: “Imagine a computer program so clever, it senses the level of pain a patient is in and measures the exact amount of pain-relief and sedative drugs they need.” This is crucial, because it not only calls the computer “clever”; it says that pain, something subjective, has become measurable by a computer. Embedded in this sentence is the conflation of subjective experience and bits of information.

Even though this technology is very important, and it’s something I’ve worked on myself for many years, the news report on it is mired in clichéd dogma about artificial intelligence. This just happens to be today. Really, this could be any day. It’s a constant drumbeat. When the language with which we talk about technology intrinsically denies subjective experience, I think it does damage: It does damage to the technology itself. It does damage to how people think of themselves. It destabilizes the world.

Cooper: You lecture to select groups about this issue. Why not a more general audience?

Lanier: I’m trying to reach the individuals who have the power. There’s no use telling someone who’s using Microsoft Word that it will eventually change their idea of themselves and harm their definition of personhood. What can they do about it?

Cooper: And would they believe you?

Lanier: Actually, I think they would, because there’s a widespread distrust and resentment of technology. But I can’t really give them any practical advice. I mean, what can I tell them? To be even more angry at their computer? [Laughter.] What I try to do is reach the young engineers who are designing these computer programs.

Cooper: What about the role of government in this?

Lanier: The role of government is vital, and it has shifted. The computer started off very much within the confines of the Department of Defense. It was like the atomic bomb: something for the best mathematicians to huddle around in secret in a secure facility. And the earliest commercial adaptations of computer technology arose from that culture, with IBM being the emblematic example, where you had very centralized control.

Small, cheap computers were supposed to create an open digital culture with lots of room for entrepreneurs. And it was like that in the nineties for online businesses. But the government has ended up taking the side of monopolies. So now you have vertical integration of computer and software products: in other words, someone can say, “I will sell you a computer, but only with this software in it.” The Windows monopoly was a surprise to me, because in the legal thinking of the late seventies and early eighties, such a monopoly would have been illegal.

Cooper: Last week at the Global Business Network, you gave a talk entitled “An Optimistic Thousand-Year Scenario.” Why should we be optimistic?

Lanier: That talk was a sort of macho exercise. I’ve decided pessimism is for wimps. It’s too easy to give a pessimistic future scenario. I could spin out quite a few credible ones, particularly right now, as we are facing some enormous dangers. But what bothers me is that there haven’t been any credible optimistic long-term scenarios lately. In the 1960s there were a host of optimistic voices, from Martin Luther King Jr., who had a vision of how society and human relationships could progress, to Star Trek, which foresaw a world in which moral improvement was tied to technological improvement. I can’t think of any popular science fiction within the last ten years that has a similar sense of optimism. The Matrix, The Terminator, Minority Report — all these future scenarios are just dismal.

Cooper: Can you give some examples of an optimistic scenario?

Lanier: In general, the optimistic scenario would be that whatever happens will be slow and voluntary, rather than fast and involuntary. That’s a crucial distinction. I’m not against change, either to our belief systems or to our genetic makeup. I think life depends on change, and to insist on keeping things the same would be to choose death over life. The crucial thing, though, is that change ought to happen at a reasonable rate and as part of a moral and ethical process. If change becomes an amoral process that just happens automatically — or is allowed to happen “naturally,” as some suggest it should — then I think we’ll lose ourselves.

Cooper: Isn’t it human nature for us not to change at a slow and thoughtful pace?

Lanier: No, I don’t think so at all. “Human nature” is a tricky phrase. It really cuts to the core of our problem. Are people “natural” or not? The answer is up to us. We have the freedom to choose our future. As soon as you accept free will, then changes become possible that aren’t part of the natural process.

I think people need to have a healthier appreciation for the cruelty of nature. One of the unfortunate aspects of utopian culture and the Left in general has been the vision of nature as this beautiful balance that we can’t be separated from. The reverse is true: Nature is cruel. Every little feature of you, right down to the shape of your nose, is influenced by this engine of death that preceded you for millions of years. It’s the frequently horrible deaths of those who were never able to reproduce that ruled out any other possibilities. That is nature. And I think the world of moral and ethical behavior is an affront to those processes. To some degree we should be able to choose equity instead of imbalance, considered change instead of unconsidered change. In my optimistic scenario, I don’t limit the degree of change; I maximize our ability to choose the type of change.

The computer has influenced the way we think about natural processes. For instance, it’s created a sort of ultra-Darwinism, whose proponents think of evolution as a “perfect algorithm.” An algorithm is a set of computational steps to follow to solve a problem, and a perfect one would, theoretically, arrive at the perfect solution for any given problem. This approach to Darwin — which, like cybernetic totalism, proposes that people and machines might be similar — was pioneered by biologist Richard Dawkins, author of The Selfish Gene.

Cooper: How did computers bring ultra-Darwinism about?

Lanier: Remember Moore’s Law, this exponential rate of “progress” that is inevitable and perfect? Dawkins’s ideas have been used by many to suggest that there’s a Moore’s Law in biology as well; that evolution is marching ever faster and there’s this inevitability and perfection to it. But the traditional view is that evolution is messy and chaotic and that there’s nothing inevitable about it. Biologist Stephen Jay Gould talked about the possibility that if you ran evolution twice, you’d get different organisms, since tiny variations early on could send subsequent events down wildly different paths. Dawkins, though, has influenced a generation of scientists who feel that there’s this smooth upward movement that is inevitable, a sort of Manifest Destiny. Of course, it might turn out that there is an inevitability to evolution. The real test will be when we come upon alien life and see how different it is from us.

Our beliefs about evolution are important, because it’s currently our only scientific model for creativity. Nature is creative, and the means of nature’s creativity is the process identified by Darwin as “variation and selection.” This theory is profoundly amoral from the point of view of an individual, because its center is not the person. Variation and selection is a cruel process, as I mentioned. We’re all the result of violence, essentially, because our ancestors who were able to survive often did so by being more violent than others.

The clan society was the first construct to counter the general cruelty of nature. The clan created a little bubble within which there was mutual kindness, or at least tolerance, even for those at the bottom of the pecking order. It provided a reprieve from the cruel, relentless competition of nature. But cruelty reappeared in conflicts between clans, and that’s the state we’re still stuck in today. Our hope lies in increased civilization, which is different from the natural order, because civilization actually puts people first. In a way, the ultra-Darwinists don’t believe in civilization, because it tries to protect the weak against failure, and for the ultra-Darwinists failure is part of the natural order. They reject civilization in favor of this process that they imagine to be better, but they’re wrong. Civilization is better than evolution in a moral sense. That’s why people decided to have civilization: because the natural state of things was cruel and awful.

I’ve decided pessimism is for wimps. It’s too easy to give a pessimistic future scenario. . . . what bothers me is that there haven’t been any credible optimistic long-term scenarios lately.

Cooper: When you talk about a “scientific model of creativity,” would that explain how we create art?

Lanier: The kind of creativity that happens in human brains is apparently different from nature’s creativity in a way that hasn’t been explained as yet. It’s possible that other theories of creativity might eventually explain it. Treating evolution as the only model for creativity is an intellectual mistake that’s been made over and over since Darwin, although he himself was not guilty of it. Darwin was just amazingly sensible and levelheaded and farsighted. He didn’t theorize an inevitable destiny where it was all leading, and he didn’t believe it was speeding up. He would state theories he felt he could understand based on evidence and reasoning, but he refrained from making predictions. With the appearance of computers, the idea of the perfect algorithm arose, and so did this ultra-Darwinist way of thinking about creativity.

Cooper: Has the perfect-algorithm concept affected other fields as well?

Lanier: It’s had an influence in economics, especially with the neoconservatives, who think we should put the economy ahead of the people. Economists have long proposed that the “invisible hand” of the market is smarter than any person, but the neoconservatives take it one step further. They don’t think of the market as the best decision-maker, but as the only possible decision-maker. They reject any effort to create equity or balance in the system.

The development of neocon ideas happened to coincide with the production of computers in mass quantities. Before that, even the most ardent capitalists, like Ayn Rand, would emphasize the heroics of individuals. But after the appearance of computers, the romance of the individual was dropped. It still shows up in rhetoric at times, but not in policy. All that’s left is the algorithm that answers every question about nature and humans.

The problem with the market as ultimate decision-maker is whether it can be as effective and creative as natural evolution. Natural evolution takes a very, very long time. It’s possible that the economy might be effective, but it might take a billion years to work. [Laughter.]

With the neocons, however, this notion of accelerated progress crosses over to economics: the neocons believe that the economy will get better at an ever-faster rate, and that the more power you give to the market, the faster it will perfect itself. A good example is the Laffer curve, a Reagan-era economics idea that George Bush Sr. described in 1980 as “voodoo economics.” This is the notion that if you lower taxes, you actually increase government revenue, because increasing the freedom of the players in a market system makes everybody richer. I can’t imagine this silly idea would have gained traction without Moore’s Law in the background.

The difference between computer science and the economy is that the boundaries of a microchip are perfectly described, as are the requirements for it, so it’s possible for the human craft of making microchips to improve without being molested by the chaos of actual reality. You can’t apply a theory that works in this little insulated playground of Silicon Valley to the real world.

My sense is that capitalism as we know it is not like evolution, because, like computer algorithms, it tends toward all-or-nothing solutions. You tend to have either total failures or monopolies. The heart of the natural evolutionary mechanism is a sort of gradualism, and the economy as we know it is poor at that.

“Human nature” is a tricky phrase. It really cuts to the core of our problem. Are people “natural” or not? The answer is up to us. We have the freedom to choose our future.

Cooper: You wrote a letter to George W. Bush a couple of years ago.

Lanier: I think it was on New Year’s Day after the 9/11 attack. John Brockman, who founded the nonprofit Edge Foundation, had asked a group of scientists to write a letter of advice to the president.

Cooper: Did Bush ever read it?

Lanier: I have no idea. I feel funny even talking about the letter, because the country is so polarized right now that if a Democrat even says anything respectful and helpful to the Republicans, it makes him or her look bad. But whether we like it or not, Bush is our president, and I want him to do the best job he can. So I will do whatever I can to be of service to him, because I think that’s what one should do. I imagine some readers of The Sun think that’s a dangerous attitude to have toward someone who is on the extreme opposite side of so many issues from them. Yet we all live in this world together, and I hope that if we show some faith in the other side, it might be reflected back to us at some point.

At any rate, in the letter I suggested that there should be new national science projects along the lines of Apollo, with goals such as finding a new energy cycle and working on major problems that the private sector is clearly not suited to solve.

Another issue I addressed in the letter is the debate between the technologists and the spiritualists, between people who think that humans are sort of like machines and those who feel that we have a precious spiritual center. My personal sense is that there’s a connection between exaggerated scientific claims that have to do with the nature of personhood and ever-more-reactionary religious responses. It goes like this: Scientists are often trying to increase their public profile because they have to struggle for funding and compete with their peers for prestigious prizes and such. Sometimes even those at the top of their field feel somewhat beleaguered. So when the reporter from CNN asks, “What are you up to?” the scientist makes a somewhat exaggerated or sensational claim like “I have discovered the gene that controls loyalty” or “I have developed a robot that knows how to be tender and affectionate toward its young.” [Laughter.] I’m just making up these examples, but the real examples in the science news are very similar.

So this story goes out, and some spiritually minded person hears it and thinks, Oh my God, the scientists are not just trying to control physical reality; they’re trying to take over my soul. I call this the “science panic” problem.

I would point out that while every religion has its fanatic groups, I don’t think there’s ever been a time when such groups were as powerful within all of the major religions at once as they are now. You have your Hindu nationalists in India, your Islamists in the Middle East, your Evangelicals in the U.S., and your West Bank Jewish settlers in Israel. We also recently saw the first homicidal Buddhist cult, the sarin-gas cult. To have any one of them at a time would be normal, but to have them all at once — and many in pivotal positions of power — is unheard of.

The character of religious extremism has shifted in modern times. If you go back a century, religious extremists tended to be somewhat forward-looking. They experimented with different family structures and styles of dress. The religious extremists were saying, “We will define the future.” The current ones, however, are almost entirely nostalgic. There’s an extreme focus in all of them on the “good old days” and on nuclear families and traditional biological reproduction, as they perceive it.

Cooper: So where is all this leading us?

Lanier: I think it’s leading to an awful destination by any measure. The computer scientists want to take us to an amoral, bland, nerdy, pointless future, but the religious alternative is also terrifying, because it’s so absolutist. I’m trying to change technical culture, because it’s easier to alter than religious culture, and because computer scientists are a very small elite that I can actually communicate with. If we could kill ideas like artificial intelligence and bring some mathematical sanity to neoconservative economics and ultra-Darwinism, maybe we would see a more moderate response from spiritual people and less religious extremism.

Cooper: You’re on the inside of the technological world, having pioneered virtual reality. What responsibility do you hold in all of this?

Lanier: I think I do hold some responsibility. It’s hard to say precisely how much. It would be nice if there were a clear feedback pattern, so that one could understand what the effects of one’s actions are. Like anyone else, I have a tendency to want to believe I’ve had a large effect, but it’s hard to say.

Cooper: Do you see a conflict between the work you’ve done to further technology and the work you’re doing to bring more soul to it?

Lanier: What I’m trying to do is create humanistic technology. I don’t want to promote the idea that technology’s the problem and we have to retreat from it or use only the bare minimum amount of technology. The alternative to technology is the cruelty of the past. Anyone who’s willing to read history honestly will have to conclude that this project of civilization and technology has resulted in less cruelty. It has enabled new types of cruelty as well, but, on balance, there is less. Look at the technology of printing books: good books are some of the best things that have ever happened, and bad ones are some of the worst, but, on balance, books have certainly been good for humanity.

This doesn’t mean we should put all our support behind technology. That’s the wrong attitude too. What I’m saying is that technology is of such vital importance that scientists have a profound moral duty to get it right and not simply trust that some algorithm will make it all OK.