Last Christmas I traveled to Libya to meet my husband’s large Muslim family for the first time. Stepping off the plane in Tripoli, I was greeted by a massive portrait of Muammar al-Qaddafi, Libya’s dictator since 1969, his head draped in an ornate covering and his eyes obscured by 1970s-era sunglasses. From that moment on, Qaddafi was with us wherever we went in Libya. His face covered buildings, stared down from posts at the marketplace, flashed by on freeway billboards, and loomed over us in museums, shops, and hotels. My husband translated the Arabic writing beneath his picture for me: “Qaddafi, our souls belong to you.”

From the Tripoli airport, we drove along trash-strewn roads where cars careened at seventy miles per hour, their bumpers nearly grazing one another as they dodged potholes and puddles of stagnant water. My husband’s family home lies hidden in a tangled labyrinth of alleys off an unmarked dirt road. We knew we were nearly there when my husband recognized a towering pile of trash. “Unbelievable,” he muttered, shaking his head. “That pile of trash looks exactly the way it did eight years ago, when I was last here.” Now I understood why we never sent mail to his family: mail delivery — along with trash collection, street maintenance, and urban planning — is not among Qaddafi’s national priorities. Yet Libya is an oil-rich country, home to the eighth-largest oil reserve in the world.

Our first day in Tripoli, my husband’s brother — a judge and a prominent official in Qaddafi’s regime — invited us to his beautiful house for a feast. When we arrived, I jumped out of the car and spread my arms wide to hug him. My brother-in-law deftly leapt to one side with an expression of alarm, leaving me grasping at air. His children watched wide-eyed as I recovered my balance. This brother-in-law, a conservative Muslim, would avoid shaking my hand, or even making eye contact with me, throughout our visit.

My female in-laws wore floor-length dresses and head scarves and gathered in animated circles on the floor, apart from the men. Lounging on pillows and sipping sweet, strong tea, I let their Arabic words and laughter wash over me. Sometimes, watching my mother-in-law shuffle around her cold, sparse home in threadbare socks, I felt sorry for her. Other times I envied the intimacy these women clearly shared and the slow pace of their daily lives, devoid of my typical American concerns: balancing career and family; saving for retirement; trying to stay fit and thin.

More than once, Libyans asked me why President George W. Bush had chosen to invade Iraq, and yet decided to repair relations with Libya. Qaddafi is a far worse dictator than Saddam Hussein was, they said. People voiced heated criticisms of the U.S. — and equally passionate desires to move there. The American dream, I learned, was also the Libyan dream. All the people I spoke to longed to be able to express themselves freely, to improve their lives, to secure an education and a promising future for their children. But under Qaddafi’s iron-fisted rule and nearly two decades of economic sanctions, these dreams have become unreachable for most Libyans.

Each morning, awakened at dawn by the call to prayer from the local mosque, I lay in bed and tried to sort out all that I had seen and heard. What, I wondered, was the difference between Saddam Hussein and other dictators in the Middle East? How had the prophet Mohammed viewed women? What did Islam teach about violence? What, if anything, did Muslim terrorists have in common with my humble and generous in-laws? And how did Muslims around the world view Americans? Once back in the U.S., I decided, I would seek out a progressive Muslim voice to address these questions and others.

Ebrahim Moosa is a professor of Islamic studies at Duke University whose services are in great demand these days. He has been called upon by UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan to serve with a group studying governance in the Muslim world, and he was recently named a Carnegie Scholar and awarded one hundred thousand dollars to write a book about madrasas, the traditional Islamic schools he attended as a youth.

Moosa is a rare scholar whose worldview is shaped equally by traditional Islamic schooling and Western academia. The son of a grocer of Indian heritage, Moosa grew up in a traditional Muslim home in Cape Town, South Africa. At the age of seventeen, he abandoned his plans to become an engineer in order to study Islam. Against his parents’ wishes, he enrolled in one of India’s foremost Islamic madrasas — an austere, male-only institution where he pored over theological and legal texts for three years, completely cut off from the outside world. By his third year, Moosa had grown restless with the isolation of the madrasa and its parochial view of Islam. He longed to engage the world more directly, and so, after earning his degree as a Muslim cleric, he traded his robes for a suit and became a journalist in London, England. As the antiapartheid movement gained momentum, he returned to South Africa to pursue a doctorate in Islamic studies from the University of Cape Town.

Moosa soon made a name for himself as an activist who not only rallied against apartheid, but also spoke out against injustice within the Muslim community. One night, after he’d criticized the use of violence by a fundamentalist Muslim group, a pipe bomb exploded in his living room. Luckily he and his family were watching TV in a rear bedroom. Within two months, Moosa had moved his family to Palo Alto, California, where he took a position as visiting professor at Stanford University. While at Stanford, Moosa delivered a commencement address in which he warned of international outrage over the double standards in U.S. foreign policy. “Even those of us who think we are safe and secure from the anger of the disgruntled and teeming millions can no longer be safe in our own homes and lands,” he said. “We sleep uneasy if people are hungry and angry, even if they are continents away.” It was June 2001, just three months before the terrorist attacks of 9/11.

Driving to Moosa’s house in Durham, North Carolina, I was struck by how far he’d come from the South African neighborhoods and Indian seminaries of his youth. His home is tucked away in a typical American suburb of cul-de-sacs and neatly mowed lawns. Moosa answered his door in casual clothes and socks, smiling broadly and gripping my hand in a warm greeting. He served me a cup of Indian chai, and for the next three hours we sat in his living room and talked. Moosa spoke passionately, leaning forward and waving his hands for emphasis, and sometimes surprising me by breaking into contagious laughter.

EBRAHIM MOOSA

Bremer: How would you define Islamic fundamentalism?

Moosa: First of all, I think many Westerners mistakenly believe that all observant Muslims are fundamentalists, because they all fulfill the “pillars of Islam,” which include daily prayer, fasting during Ramadan, and a pilgrimage to Mecca. Most Christians think one day a week is enough to pray, and Muslims pray five times a day. They must be fundamentalists! And when Christians hear that Muslims don’t even drink water during Ramadan, they think that’s terrible — a violation of human rights! And when they hear about the animals killed for feasts during the pilgrimage to Mecca, they think that’s an “orgy of blood.” In short, Americans and Europeans are accustomed to seeing religion practiced a certain way, and when they see something else, they call it “fundamentalism.”

Historically, Muslim societies have understood that in certain arenas, the voice of religion prevails, and in other arenas, the voice of reason prevails. Thus, questions about how you worship God and how you perform your rituals would fall under religious authority. But how do you build roads? How do you organize your banking system? How do you handle agriculture? These questions require the authority of reason. Islam has had very little to say about these issues for most of its history.

Bremer: But my understanding is that the prophet Mohammed laid out very clear instructions about civil society, in addition to his teachings on the inner world.

Moosa: Mohammed gave us a model of how religion and the worldly realm can inform each other, but that doesn’t mean that Muslims are called upon to duplicate those exact same institutions and practices for all eternity, because some of them just won’t work anymore. In the past Muslims understood that the message of Islam is contained in very specific teachings, and that other teachings in the Koran are very Arabian in character. Unfortunately, some present-day Muslims — and they are properly called “fundamentalists” — do not look at the historical context of the Koran’s teachings, and so they want to transplant those Arabian teachings exactly as they are into twenty-first-century society. Such modern Muslim fundamentalists are like engineers who read the Koran as a technical manual, but the Koran was not made for such use. That’s why, for centuries, when Muslims have had a problem, instead of going to the Koran, they have gone to Koranic scholars for an interpretation of the teachings.

Take for example the way the Koran deals with women. Mohammed clearly made an attempt to loosen the grip of the brutal patriarchy that existed during his lifetime. True, the Koran didn’t completely outlaw patriarchy, but this doesn’t mean that patriarchy is desirable, from a Muslim point of view.

Bremer: How did the Koran elevate the status of women at the time?

Moosa: For instance, in Arabia, before Islam, the marriage dowry was given to the bride’s father, so it was more of a bride price. The Koran said that the marriage dowry must be given directly to the bride as a gift to win her affection. A gift encourages certain bonds of caring between two people.

Mohammed was no feminist, and we would be foolish to claim otherwise, but he clearly thought the emancipation of women was a good thing. He set the momentum for change in the direction of freedom for women. Some Muslims have continued in that direction, while others have arrested or reversed that momentum. And each time Islam moved into neighboring cultures, it encountered different kinds of patriarchy, resulting in different interpretations of the teachings.

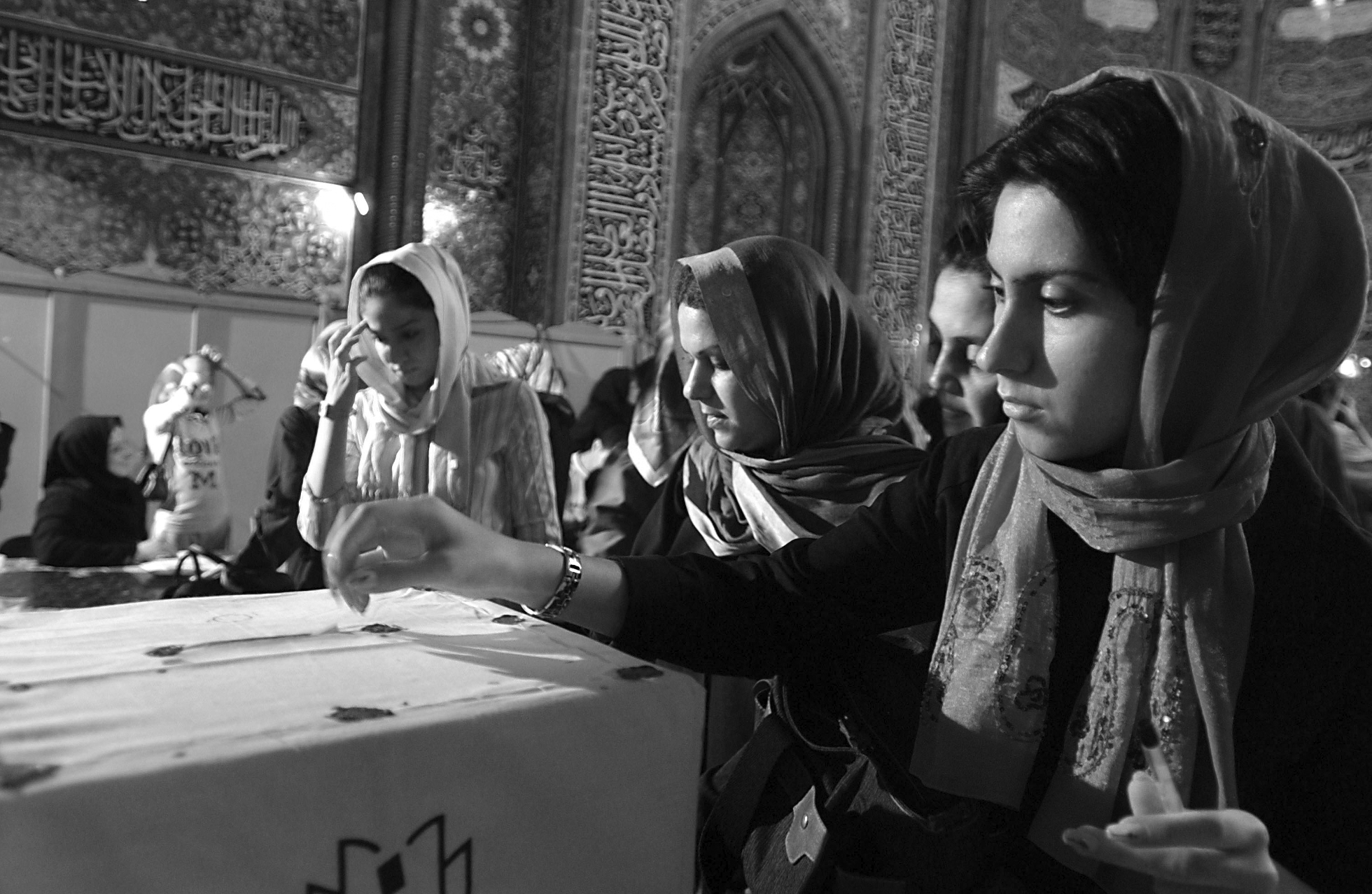

In a society like ours, where we no longer see patriarchy as desirable, the big question is: How do we create a new Islamic system of gender equity, where women are no longer seen as subordinate, are no longer illiterate, and are no longer dependents? In other words, how do we interpret the Koran now that women are a part of the economic engine of society, producers and consumers of wealth? That’s where the challenge lies for Muslims: to reexamine the teachings in light of the current cultural reality.

Bremer: Having lived in both the East and the West, what have you observed about the relative status of women in each place?

Moosa: Westerners feel that Arab, African, and Asian Muslim women are direly oppressed compared with women in North America and Europe, but these judgments are relative to where one stands. I’ve had women in the Middle East tell me they are quite comfortable the way they are. And I’ve also heard women in the Middle East complain that they are under the control of their fathers, brothers, and uncles, and their lives are miserable.

In Middle Eastern societies today, women are exposed to international media, which tell them that to take off as many clothes as possible equals freedom; that to separate oneself from family, to be economically independent, and to be able to terminate a pregnancy equals freedom. These messages create conflict within cultures where to be free might mean to be part of a family, or to be married, or to produce as many children as possible. To women in some cultures, the pinnacle of freedom is to have many children and become a matriarch, and the greatest suffering and shame is to be single and lonely in your old age, and not surrounded by family. Yet in our society, to be childless and economically self-reliant in one’s old age is the ultimate freedom.

These values stem from different economic practices. When you have Social Security, and you have a paycheck coming in from age sixteen to sixty, and you have health insurance, and you’ve accustomed yourself to independent living, then you train your desires accordingly, and you might find having the quiet time to read a novel the highest form of happiness. Meanwhile, in another society with different economic practices, the highest form of happiness might mean to be surrounded by people all the time, to eat lots of food, and to have animated conversation.

Unfortunately, people all over the world are being hit by another form of fundamentalism — namely, capitalism. Capitalism wants people everywhere to consume in the same way, so that it can grow without end.

In December 2004 I returned to my ancestral village in India, where my great-grandfather came from, to visit my extended family. When my relatives talked to me or others who had gone abroad, they perceived that we had a more desirable lifestyle. If only their great-grandfather had left the village, as mine had, their children might have been teaching at Duke today. But before they talked to me, when they had no basis for comparison, they were happy tilling their fields and living their lives. It’s only in comparative situations that things begin to look unequal. You’ve been to Libya; you’ve seen what I’m talking about.

Many Westerners mistakenly believe that all observant Muslims are fundamentalists. . . . Most Christians think one day a week is enough to pray, and Muslims pray five times a day. They must be fundamentalists!

Bremer: I have. My husband and I brought all the members of his large family gifts of clothing, shoes, and the like. When they opened the gifts, however, there was a sense of disappointment. “This is all you brought us?” my brother-in-law said. “But you are so rich; you must make fifty thousand dollars a year in the United States!”

Moosa: They don’t understand that the fifty thousand dollars goes to pay your mortgage, your living expenses, your debt. If they looked at what you’re saving, they might be surprised to find that, in relative terms, they’re saving more than you. Still, their conditions could be improved.

Bremer: How could their conditions be improved? To what extent would our lifestyles have to change to establish more equity around the world?

Moosa: Tremendously. The world cannot support the modern American lifestyle for everyone; there simply are not enough resources. In order for us to wear Nikes, people elsewhere have to work very, very hard producing those shoes at a fraction of a living wage. We might believe that we’re creating employment, but we’re really creating misery.

To make sure there is a minimum living standard elsewhere, we have to limit our own consumption. Consumption patterns and greed, not religion, are the causes of war. Religions become the catalyst, but they are not the root cause. And greed is a problem not only among Western societies; it’s also present in Middle Eastern societies. There are terribly greedy people all over the world.

Bremer: We tend to lump all Muslim opposition to Western culture into the category “Islamic fundamentalism.” Is there a progressive Muslim voice of opposition to the West, and what is it saying?

Moosa: Progressive Muslims are mostly challenging Muslim authorities who are turning Islam into a tool of oppression. They have been less prone to critique U.S. foreign policy and support for totalitarian governments in places like Pakistan, largely because political protest often involves risk. And progressive Muslims are a kind of endangered species, loved by neither the religious authorities nor the political ones.

There is an emerging progressive Muslim voice here in the U.S. that is trying to remind American society of the foundation on which this country was built. The task of all progressives in America — not just Muslim progressives — is to ask: Are we living up to those values? Or are we instead abusing the rhetoric of freedom, insisting merely that other people be more like us? Progressives must refuse to give in to the lack of will and imagination among dominant conservative groups. They have to create solidarity across religious and political divides. In all societies, progressives will always be a minority; their role is to be the culture’s conscience.

Bremer: You’ve expressed disappointment with the failure of academics and journalists to question U.S. foreign policy after September 11. Why do you think this failure took place?

Moosa: On some level, it’s a matter of self-interest. As members of this society, journalists and academics buy into a certain set of values and become dependent on material possessions. And they see that if U.S. foreign policy were to change, their lifestyle would have to change.

You see, to criticize U.S. foreign policy — and, in particular, our policies in the Middle East — means to tell Americans that they must pay the true price of a barrel of oil, in the same way that people in Indonesia and India have to pay the true price of Microsoft software or Ford automobiles. In order to keep the price of oil — and countless other resources around the world — sufficiently low, the U.S. is willing to become a bully. And we’ve all become complicit in this complicated dependency cycle. Even immigrants who come to this country quickly become less critical of the U.S. than they were when they lived abroad.

Muslim immigrants who’ve been here a long time also like to lecture Muslims abroad about how they’re not running their country right, and they don’t know their faith properly, and so on. This is an internalization of the American attitude of paternalism. What these critics don’t realize is that we are citizens of the biggest consumer society in the world, and our desires actually create some of those conditions they criticize. And, in truth, they don’t want those conditions to change, because if they did, our lives would have to change as well. If, for instance, there were a democratic government in Saudi Arabia that acted in the interest of the Saudi people, then that government would require us to pay a reasonable price for a barrel of oil. A democratically elected leader wouldn’t be bought off at the Bush ranch in Texas, making sweetheart deals while posing for the camera holding hands with President Bush.

People in Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, and Egypt are being repressed by regimes that, directly or indirectly, have the blessing of Western powers. Pakistan’s Pervez Musharraf is a military dictator who is stifling democratic possibilities in the region, yet the U.S. calls him a “good dictator” because he’s helping us capture al-Qaeda members. Meanwhile, millions of Pakistanis are suffering under his rule, and there is no hope of democracy in Pakistan. Over the long term, this approach is not good for our society, because these unsavory relationships enable us to fulfill our needs with cheap goods, cheap labor, and cheap gas, creating false expectations that are not sustainable.

Mohammed was no feminist, . . . but he clearly thought the emancipation of women was a good thing. He set the momentum for change in the direction of freedom for women.

Bremer: Have you adapted your own lifestyle to address this reality?

Moosa: To be honest, I’m still trying to understand how to address these issues adequately in my own life. I try to drive less, to recycle whatever I can, to avoid supporting corporations that are engaged in exploitative patterns abroad. There is no easy answer to this question, except to grapple with it and to end one’s complicity in symbolic ways.

Individual acts of protest alone, however, are not a solution; we must achieve critical mass. I believe the challenge at this point is to raise awareness about these issues. Our politicians tell us that our enemy wants to change our way of life. The fact is that either we will be smart enough to change our own lifestyle, or it will be changed for us, because this way of life is not sustainable.

Bremer: Some in the West think that Islamic terrorists are inspired by the Koran’s teachings to commit acts of violence. What does the Koran say about violence?

Moosa: Again, for centuries Muslims did not follow the literal word of the Koran. The Koran was combined with the prophetic traditions and an understanding of the world at large to create an interpretive platform. Today’s Muslim fundamentalists want to reduce Islam to the Koranic text, without any consideration of history — and this is exactly what progressive Muslims are fighting against.

Part of the problem is that, now that more Muslim people have become literate, they can go directly to the Koran, which is a very difficult document to interpret. So they might read one verse that says, “Kill the infidels wherever you find them,” without knowing that this verse was written at a time when Muslims were at war. This is war talk, the product of a particular historical moment, not the rule for all eternity. The rule for all eternity is that if your enemies concede to peace, then you must turn to peace, too. Even if your enemies intend to deceive you through peace, you must yield to peace: you must always give peace a chance. The overriding sentiment of the Koran is peace at any cost, even if it is to your disadvantage.

Bremer: What about jihad and its violent connotation in the media?

Moosa: Jihad means “struggle.” When Muslims were a besieged and repressed minority in Mecca, jihad meant “resistance”; it meant suffering the oppression of the dominant society in Mecca, but not giving in to it.

The use of force and violence is subject to all kinds of restraints in Islamic law and ethics. Only a legitimate state may declare war or decide when force must be used, and even then it must be exercised with great caution. Individuals who take up arms and act independently, as we saw on September 11, are traditionally seen as bandits or rebels.

But during certain historical moments, when Muslims have experienced tyrannical, oppressive governments, some scholars of Islam have claimed that individuals have the right to resist tyranny. Of course, this interpretation is very controversial, but that’s where this notion — that a small group of people, acting as moral correctors of society, could use violence — got its legitimacy. And political repression is so bad in various parts of the Muslim world today that they have become factories for rebellion, which is usually called “terrorism” in the U.S.

For example, in Egypt and Saudi Arabia, where political repression is pervasive, the only way people can articulate their frustration and anger is through religion. And that’s where fundamentalism emerges. It provides a narrative of emancipation. In verses of the Koran, people find the permission to rebel and free themselves from tyranny. And they use violence to do so, believing that they are creating a better society. But fundamentalism is just a different form of totalitarianism; both speak the language of violence.

The regimes we support in Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt invite fundamentalism because they leave no room for rational political discourse, for voicing one’s opinion through elections, for working within the system to remove people from power. Citizens come to see violence as the only option.

The problem with the “war on terror” is that it fails to identify the causes of terror. We don’t need a war; we need a global dialogue to stop the engine of terror. One thing that George W. Bush is right about: he says people need freedom. Unfortunately, he’s either incapable of seeing, or unwilling to see, the oppression caused by the tyrants with whom he has allied himself. Musharraf, Qaddafi, the Saudi royal family, the leader of Uzbekistan, the head of Tunisia, the head of Algeria — Bush is in bed with all of them while claiming to fight terror. Not only do they support the U.S. “war on terror,” they actually use it to their advantage.

Take Egypt. For years, only the ruling party in Egypt could field candidates for the presidency. One could not create an opposition political party without permission from the ruling party, and of course it wouldn’t grant permission to any viable competitor. There is a party in Egypt called the al-Wasat Party — literally, the “Moderate Party” — that has been applying for the last ten years to become a legitimate party. Over and over again, it has been denied. So, lacking other options, this party engages in illegal underground political organization. Now Egypt is claiming that the al-Wasat Party and other underground political parties are terrorists. Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak tells Bush that it’s in America’s interest that he, Mubarak, stay in power, because otherwise the terrorists will come to power. All these totalitarian rulers have to do is say the T-word, and U.S. politicians get shivers up and down their spine.

Bremer: Given your antipathy toward totalitarian regimes, how do you respond to the invasion of Iraq and the overthrow of Saddam Hussein?

Moosa: No one can dispute that Saddam Hussein was a loathsome and offensive man. He was bad news — and so are the leaders of Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Tunisia, Pakistan, Libya, and the rest. I believe all those regimes have to be overthrown, but the only legitimate way for this to happen is for the citizens of those countries to overthrow their rulers. We had several opportunities to help the Iraqi people overthrow Saddam, and each time, we refused to come to their aid. For a long time we didn’t want to overthrow Saddam. He was a “Made in America” product.

Bremer: How so?

Moosa: When Saddam came to power, the U.S. gave him a long list of Iraqi communists to “eliminate.” He got rid of a number of them and slowly ingratiated himself with Western powers, especially the U.S. Later, through go-betweens Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld — who are now, respectively, Bush’s vice-president and secretary of defense — the U.S. supported Saddam in Iraq’s war against Iran. But there is no way to switch off a tyrant like Saddam, and he eventually began to cause trouble where we didn’t want him to.

So for us to claim we had nothing to do with his tyranny is ludicrous. On the contrary, we knew everything he was doing, but as long as it was in what we considered our interest to let him do it, we looked the other way.

The U.S. can no longer expect the world to look the other way and ignore our abuses of power; nor, when the U.S. chooses to look the other way, can we expect the world to excuse our behavior. The terrorists are holding Americans culpable for their country’s international abuses and omissions. And that is what virtually no one is prepared to tell Americans, and what they have a great deal of difficulty accepting. Americans even take offense at hearing this truth spoken, because it seems to legitimize terror. They don’t want to acknowledge that “winning” this new war is going to require us to be world citizens, to act morally on a world stage.

Bremer: When speaking to people from the Middle East, I’ve noticed they have a much greater awareness of the historical relationship between the Middle East and the U.S. than do Americans.

Moosa: That’s because the U.S. is such a consumerist country. The newest brand name wipes out the one we used last week. Similarly, as soon as a new president takes over, we forget what the previous one did. Yet we remember that Iranians took over the U.S. embassy in 1979. This country’s selective memory is a form of pathology. Americans remember the hostages in Iran, but forget that a U.S. Navy cruiser blew up a passenger plane full of Iranians in the 1980s. This country shot a plane full of innocent civilians out of the sky over the Persian Gulf, and, to date, no reparations have been given, no apologies offered, no acknowledgment made. But everyone remembers the TWA flight over Lockerbie, Scotland. That is a pathology of remembrance, a kind of self-serving forgetfulness that is built into the U.S. media and even the educational system. People here are not taught about the ugly side of U.S. history.

Bremer: As a Muslim, how do you respond to the Iraqi insurgency?

Moosa: The insurgency in Iraq is a legitimate attempt to overthrow a foreign occupation. It is brutal, but we started this war, and now we don’t want to suffer the consequences. Not only did we start the war; we got other countries involved and put Iraqis at war against one another.

Resistance to foreign occupation is a legitimate right under both international law and Islamic law. Right now the situation in Iraq is clearly an immoral one, with people dying every day under the Americans’ watch. Perhaps more people died under Saddam’s rule, but do we calculate morality on the basis of simple arithmetic? By helping put Saddam in power, we created the situation that supposedly necessitated this war. We actually aided and abetted his killing of thousands of Kurds: the chemical weapons he used against both Iranians and Iraqi Kurds were made in Virginia.

There are some very good people in Iraq who are part of the interim government — people who have made huge sacrifices for Iraq. Some lost dozens of family members to Saddam; others spent decades in exile. By being associated with U.S. power, however, these good people will lose credibility over time in the eyes of their fellow Iraqis. The best thing would be for the Americans to withdraw as soon as possible, and for the Iraqis to be left alone to fight it out, the way Lebanon did. It would be a blood bath, but it’s a blood bath right now, and our presence is creating no security.

The use of force and violence is subject to all kinds of restraints in Islamic law and ethics. Only a legitimate state may declare war or decide when force must be used, and even then it must be exercised with great caution.

Bremer: Both progressives and conservatives in this country have expressed concern about a democratically elected Shiite majority ruling Iraq. How would you respond to that concern?

Moosa: We should not be surprised that a religious party can come to power through democratic elections. They have the Christian Democrats in Germany; why should an Islamic Shiite party be any more offensive? This is a flaw on the part of the Left and progressives in this country who see all religion as bad, and who take a paternalistic attitude toward those who think otherwise. They don’t understand that attitudes toward religion are different in other parts of the world. If we believe in pluralism and diversity, then we should let people around the world elect the governments they choose.

Bremer: So separation of church and state isn’t a prerequisite for democracy?

Moosa: I don’t think so. It is a prerequisite only if the type of democracy that we have in the United States is the only real form of democracy. But there are different kinds of representative government. It’s authoritarian to force a single model of democracy onto the rest of the world. We have to accept that some people might choose an ayatollah as the head of the government, or a priest. And why not?

Bremer: Can you explain the Muslim concept of umma, and how it amplifies the outrage over our actions in the Middle East?

Moosa: In Islam, umma signifies a community of people who are united by their commitment to faith. Muslims form a global faith community that transcends the nation-state. When one thinks in terms of umma, one doesn’t think of borders. To a Muslim, it doesn’t matter whether it was an Iraqi, an Indonesian, or a Turk who got killed, because these labels are an accident of birth; what matters is that a fellow Muslim got killed. This concept of umma creates a deep sense of solidarity among Muslims.

In this era of globalized media, Muslims are much better informed than they were in the past about the plight of other Muslims around the world, so it’s not surprising that they feel a very strong sense of outrage. In remote villages in Indonesia, people know that Americans are torturing Muslims.

I don’t want to give Muslims a pass, however, because they have been blind to the torture and repression of their own people by their own people for too long. Unfortunately, there’s a certain amount of tolerance when Muslims abuse one another. I think that’s partly how we arrived at the current situation in Iraq: too few Muslims spoke out against Saddam Hussein’s atrocities — especially Iraq’s Arab neighbors and all the Muslim countries that were taking Iraq’s oil: Pakistan, Indonesia, Malaysia. Not one spoke up about the tens of thousands of people Saddam killed. So it’s not only American complicity, but also Muslim complicity that contributed to the crisis in Iraq. The same thing is happening today with this madman Qaddafi. The minimum responsibility Muslims have is to speak up against all the Muslim regimes that are brutalizing and torturing their people.

Bremer: It’s impossible to discuss politics in the Middle East without discussing Israel. From a Muslim perspective, is the Arab-Israeli conflict a religious one?

Moosa: In the early days of Islam, there were problems between Muslims and Jews in the Arabian Peninsula. So one does find passages in the Koran that talk about Mohammed’s conflicts with Jews. But there are also passages in the Koran about Jews who are friends of the Muslims. How can Islam be anti-Jewish when Jesus, Moses, David, and all the prophets are presented as role models for Muslims? So although there has been some competition between Muslims and Jews historically, I think most Jewish scholars would agree that tolerance and coexistence have characterized our shared history.

But with the creation of the State of Israel, a different form of Judaism came into being, one with very strong exclusivist pretensions: the notion of cultural Zionism. And one Muslim response has been the revival of the rhetoric in the Koran that criticizes the Jews for claiming to have the exclusive privilege of God. This is the Koran’s biggest objection to Judaism: that it claims it has God’s privilege and attention above all other faiths. Unfortunately, Zionism just reinforces that belief with its claim of divine rights to a particular piece of hotly contested real estate — regardless of the misery that results for the Palestinians who are living there.

Bremer: But doesn’t Islam make the same claim — that it has God’s exclusive privilege and attention above all other faiths?

Moosa: Islam claims that it is a completion of divine revelation, but it also states that salvation is available for Jews, Christians, and others through their own paths. There are both narrow and broad interpretations of that statement, but I think even the harshest critics of Islam can’t deny that it acknowledges the possibility of salvation through other faiths.

Bremer: How do Muslims think the U.S. benefits from its support of Israel?

Moosa: Most people in the Middle East believe that the U.S. supports Israel in order to keep Arabs fighting and to destabilize the region. This instability justifies a Western military presence there, thus facilitating Western access to the region’s oil resources.

Israel’s heavily armed presence also keeps the price of oil down. If the Saudis try to raise the price, the U.S. can suggest that the Israelis are not very happy about the presence of Saudi fleets in the Red Sea, adding that if Israel chooses to attack Saudi Arabia, the U.S. won’t be able to help, because Israel is our ally. Then Saudi Arabia must rethink its position, for the Saudis would rather drop the price of oil than face an attack from Israel.

There’s also a belief among most progressives in the Middle East that the tyrannical regimes there consolidate their power by playing the Israel card. The tyrants claim they have to maintain a heavily armed police state because Israel is around the corner. That’s how Iraq, Syria, and Jordan all justify their oppressive states. In that sense, the presence of Israel is actually a gift to the Middle East’s tyrannical regimes.

To a Muslim, it doesn’t matter whether it was an Iraqi, an Indonesian, or a Turk who got killed, because these labels are an accident of birth; what matters is that a fellow Muslim got killed.

Bremer: George W. Bush says the terrorists hate our way of life. Is Islamic fundamentalism a reaction against capitalism and modernity?

Moosa: I don’t think so; in fact, I think fundamentalism has a lot in common with modernity. Here’s what I mean: Modernity presents itself as the ultimate solution to the dilemmas of the human condition, while at the same time turning the old stories of religion into myths that are no longer relevant. According to modernity, we no longer need to wait for salvation in the afterlife: salvation is here on earth. Modernity claims that the end of history is here.

In some ways, Islamic fundamentalism makes the same claim. Fundamentalists say they are going to make the ideal world right now, and anyone who dares stand in their way is God’s enemy.

Traditional Islamic discourse, by contrast, teaches that what you cannot get in this world or this life, you’ll get in the next. There’s always room for something to be deferred, to be delayed, to be fulfilled in another place, at another time. When you have those kinds of beliefs, your sense of time is not that urgent.

Bremer: So you’re saying that fundamentalism is not so much a reaction to modernity as an adaptation of it?

Moosa: Exactly. Islamic fundamentalism is a modern discourse, and it is very much at odds with traditional Islamic discourse. Just like capitalism, fundamentalism believes in attaining heaven on earth. And that is a fatal combination. Islamic fundamentalists do not criticize capitalism; they play with it.

Bremer: How do you mean?

Moosa: Capitalism is a godsend to Muslim fundamentalists, because, like many Christian fundamentalists, they want theologically to justify the accumulation of wealth and the idea that the rich must get richer. They might acknowledge some minor responsibility of the rich toward the poor, but, overall, fundamentalists see wealth as a gift God bestows on the faithful, a demonstration of his beneficence and grace. Therefore, the rich can continue doing exactly what they want. This mind-set conforms perfectly to capitalist logic.

Actually, the Middle East wants very badly to be like the West. This is one aspect of the love-hate relationship between the Middle East and the U.S. that Americans don’t understand. The obsession with all things Western is evident everywhere. Go to any Middle Eastern country, and you’ll see that the recent architecture is not Indian, Pakistani, or Malaysian in style; rather, all new buildings are European and American in appearance. And the people love it — much to my disappointment. They want to be like the West, and the West just continues to kick them in the teeth. That is the sad irony of the situation.

In fact, even bin Laden and his cohorts are saying, in effect, “We want societies like yours.” They might not like the moral freedom, the promiscuity, and the sex (although perhaps they would like the sex, only their religion won’t allow it), but they admire our law and order, our technological savvy, and all the rest.

Both Bush and bin Laden claim to have divine mandates, to have access to secret spiritual knowledge that obliges them to do certain things, even if those things run counter to their respective religions’ most basic ethical teachings. Both men claim they’re going to save people through their actions. But when world leaders believe they have a messianic mission to fulfill, they delude both themselves and their followers. It is an abomination and the very antithesis of religion.

Bin Laden’s fundamentalist strategy is the same as the U.S. military strategy of “shock and awe.” From the atomic bombing of Hiroshima to Agent Orange and napalm in Vietnam, the U.S. military has repeatedly used that strategy. And what was the logic? That we would kill a couple of hundred thousand people in order to save countless more. When bin Laden uses that logic, we call it “terrorism.”

The irony is that most Americans think they are moral, yet remain unconcerned about the immoral way their government exercises power. That’s what I find hardest to understand: the level of self-delusion that Americans allow themselves. Then again, I suppose that if Americans really thought about what their government is doing, they might go crazy.