We use cookies to improve our services and remember your choices for future visits. For more information see our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

Chicken. Film. Youth.

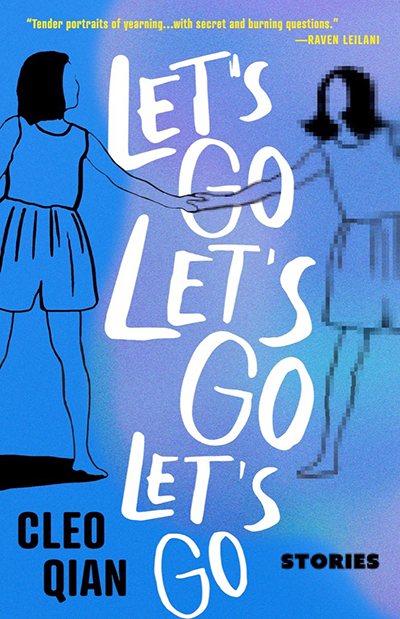

An Excerpt from Let’s Go Let’s Go Let’s Go

We are pleased to share “Chicken. Film. Youth.” an exclusive online excerpt from Cleo Qian’s new short-story collection, Let’s Go Let’s Go Let’s Go, available August 15 from Tin House.

It was hard to articulate the point at which we switched from wanting to get older to feeling like we could stand to be a little bit younger. Perhaps there had never been a point when we really felt like we wanted to be older, only to have the things we thought being older entailed: freedom, money, privacy, love. But it had always been true that if we were a little bit younger, a little bit fresher, then we’d be a little bit better.

It was raining in LA, a slurry of wet in a city never designed for it. Water poured down from rooftops and pooled in inconvenient potholes. Aggressive Porsche 718s and equally aggressive Honda CR-Vs competed on right turns, raising miniature tsunamis over the sidewalks. Sitting by the windows of Mr. Kang’s chicken restaurant, we watched the rain drizzle over the billboards and blinking lights advertising the other stores in the strip mall: the Thai restaurant, the shaved-ice cafe, the boba-and-crepe shop, the Tofu House, and the aspirational artisanal grocery store with the twenty-six-dollar charcuterie plates. The rain made the strip mall look muted, pretty, the neon lights taking on a fairy-tale aura as they blurred through the pane.

“Half-and-half spicy sauce and soy garlic,” Mr. Kang called out.

“Grab some radish, too,” Dake reminded me as I pushed my chair back. When I put the tray on the table, he said, “This chicken looks amazing.”

The fried chicken, unveiled from its styrofoam lid, glistened with a honeyed texture. Underneath its sprinkling of white sesame seeds, the skin of the chicken pieces beckoned with its coy, crisp, perfectly golden color. In an unusual move that had given this restaurant its write-up in the Times, the chicken was layered with a hearty handful of cut fruit: avocado, raspberries, blueberries, and a few slices of jalapeño. When we bit in, the meat was warm, moist, and tender. Eileen mmmed. The glazed fruit added a startlingly light contrast to the meat.

Jessica sucked on her iced water. The rest of us all had beers. Jessica was a killjoy who cared about calories. And something about how alcohol caused skin aging? When she was a kid, she had entered into beauty pageants. She wore little tiaras, had skin so bright and glowing it was like her face was a spotlight. Now she was still pretty, but she wasn’t a pageant winner. She was a dental hygienist. She wore fuzzy cardigans and circle lenses. Every year she spent hundreds, if not thousands, on skincare, makeup, and lash extensions to keep her three thousand Instagram followers and trickle of occasionally fraudulent sponsorship offers, but hey, what else could she do? She was no longer twenty-two. She was twenty-eight.

We were all twenty-eight, or just about to turn twenty-nine. There were four of us: Dake, Jessica, Eileen, and me. Dake and I were high school friends. We met in LA, or more precisely, Long Beach, where we went to the California Institute of Mathematics and Science, which is a magnet school for cutthroat bitches and overachievers. It’s the kind of place where if you aren’t already taking college-level calculus when you’re in eighth grade, you’re behind. When I transferred in, Dake and I bonded over our mutual relative inferiority.

Senior prom, there had been a “let’s go as friends” date, an awkward kiss, emotional fallout, and then we stopped speaking — until the summer he was interning at Snapchat, I was interning at the LA Department of Cultural Affairs, we got lunch, and things were okay again. Sometimes I look at him and wonder a little what we would be like together, but for the most part, I leave it alone.

“Luna, tell me about you and Billy,” Eileen said to me.

“God, I can’t believe you’re dating someone named Billy.” Dake’s sardonic tone made me bristle with a slight frisson of irritation.

“I know, I know,” I said, trying to shrug it off. Billy was new. I’d run into him in a Trader Joe’s. My cart had stiff wheels. He had two towering stacks of canned San Marzano tomatoes and cannellini beans in his arms. An accidental nudge and they all came tumbling down. One can bounced off the naked toenail of my big toe. “I’m so sorry,” I gasped, as my toe throbbed. “I’m so sorry,” he gasped. He ran to find an employee to get a Band-Aid for the toe. There were no other injuries.

“Has it been awkward, you know, dating white?” Eileen probed.

“It’s been okay so far, but there are some moments where I’m like, oh, you don’t come from the same place I do. Like when we got mochi ice cream and he didn’t eat the mochi skin. He took it off and just ate the ice cream.”

I was Billy’s second Asian girlfriend, but he had dated a couple of white girls and one Latinx girl and didn’t watch anime, so I was fairly confident he didn’t have yellow fever. Aside from one ill-begotten crush on a white boy named Andrew in high school, my exes, including Kevin, a chemistry-major-now-turned-Twitch-streamer from college, Aaron, a photographer I’d met in New York, and Minji, the on-again off-again DJ ex-girlfriend I’d been entangled with in LA, had all been of East Asian ancestry.

“That could be you being classist,” Jessica pointed out, annoyingly. “Mochi ice cream is kind of bougie.”

“I guess that’s true.” I tried to concede.

It was fun to be in a relationship again, to have someone around to watch TV and do shrooms with while laughing at the dumb things people on reality shows said. With Billy, I felt safe, even a little bored. There were nights when I forgot to think about him. There were nights when, sitting next to him, I sensed that in one year, two years, even four years, I might wake up and find that all that time had passed and I was still with him, and that would not be the worst thing. This feeling terrified me.

I changed the subject. “To Eileen,” I said, cracking open a new can of Hite and raising it into the air. Ostensibly, we were gathered to celebrate Eileen’s promotion to senior marketing manager at the wellness app she’d worked at for three years.

“Oh my god, thank you,” Eileen groaned. “It’s been five years, three apartments, four terrible roommates, and a broken-down car, but I can finally upgrade to living alone now! Thank the LORD.”

Eileen was from Manhattan, and before she moved to LA, had never touched a steering wheel. Back at Barnard, we were mainly party friends: we’d meet up to pregame with shots at someone’s apartment before going out to dance sloppily with blurry strangers or text misbegotten matches from Tinder. We lost touch until I burned out on New York and moved back to California two years ago. Now she had a Class C license, a Prius, and a new job title; I was working at a nonprofit and had private healthcare for the first time in years; and our friends were being promoted to middle management and getting engaged.

The rain trickled outside. The restaurant felt private. The only other group was sitting all the way at the other end, next to a couple of pulpy movie posters with titles I didn’t know. The beer, the smell of oil, the hot food and lights made me feel woozy, dreamy. Our conversation revolved around the people we knew. Jessica had three wedding invitations for summer. Eileen’s cousin’s start-up had just IPOed. Our college friend Melissa had finished her PhD. Minji, my ex, had scored a sponsorship from The North Face. And my cousin Vicky had just proposed to her girlfriend and scored funding to lead a major new research project, something on a boat, in Puerto Rico.

“Rachel and Danny just bought a house,” Dake said.

“Oh my god, what? In LA? Where?”

“And they got a dog,” he continued.

“How did they afford a house?” Jessica demanded. “What neighborhood is it? Is it, like, a real house, or is it, like, a condo? This does not sound like a good idea. She was just thinking of breaking up with him in November!”

Dake shrugged. He worked at Facebook and probably had enough money of his own to buy a house, but was embarrassed about it. “I mean, everything’s easier with two people.”

“Are they going to get engaged, or what?” Eileen popped a radish cube into her mouth.

“Danny told me he’s planning on asking soon.” Dake’s Adam’s apple bobbed as he finished his Hite. Jessica rolled her eyes.

“One of my coworkers is going to Taiwan to freeze her eggs,” I offered.

“Oh my god! Isn’t that really expensive? How old is she?”

“She’s doing it in Taiwan because it’s way cheaper there. She’s in her midthirties,” I said, but already I felt guilty for spilling someone else’s secret. My coworker was a divorcée. Her ex-husband had always hesitated about kids and now she felt like she had waited too long for him to make up his mind. But in my mind, thirty and twenty-eight were basically the same, and people I knew might have to make similar decisions soon.

What about all our potential? Where had it gone?

“NO MORE ORDERS!” Mr. Kang shouted into the phone, and we all jumped. He slipped his phone into his apron with the energy of someone slamming down a landline.

“Should we get going?” Dake eyed Mr. Kang, whose eyebrows gave him a murderous intensity. The other group got up and bussed their trays to the trash can.

“We should be fine.” Jessica checked her phone. “It closes at nine. Ten minutes.”

“Where are we going after this? Jessica, do you have to go back?”

“No, Henry is out with his other friends tonight.” Henry was Jessica’s long-term college boyfriend. He was such a fixture that no one even thought about him anymore, like the streetlamp you walk under on the way to your friend’s house. I honestly thought he was cute; he had a quiet attention that would switch on to you like a lightbulb when he listened to you, intense and consuming. He didn’t hang out with us often. I wondered who his other friends were.

No one had asked if I was busy. No one was used to me being in a relationship yet. Billy wanted to come over tonight; we would probably watch a movie, go to sleep, and take our bikes to Frogtown in the morning, but it had been a while since the four of us had gotten together and now I didn’t want to leave.

Specifically, it was still a novelty to be hanging out with Jessica again. Not even a full year after Eileen introduced us, our fallout had culminated with me calling her a selfish, only-child bitch and her snorting that I was a codependent Negative Nancy with the impulsivity of a twelve-year-old. Eileen and Dake had shuttled back and forth between us like the children of divorced parents. Only a few months ago, when Jessica and I ran into each other at an acquaintance’s birthday party, had we started talking again. In the group chat, we were a little too eager to laugh at each other’s jokes. We didn’t mention the rupture, but she had to be thinking about it, too.

Dake scrolled Yelp on his phone. Eileen gestured at the movie posters on the opposite wall. “The Times said the owner here used to be a movie director.”

“Really?” Jessica turned to look at the posters. “So did he do those movies up there?”

I pulled up the article on my phone to check. A text message from Billy: Hey, when are you going to be done? I swiped left so the notification disappeared. “That’s wild. How did he start running a fried chicken restaurant?”

“You wanna know?”

We looked up, and Mr. Kang was standing next to our table. No one had heard him come up. His shirtsleeves were rolled, his shoulders straining the seams. His arms were crossed and his forearms looked like what I imagined Popeye’s would after he had eaten his spinach.

“Uhh . . .” We blinked awkwardly at the owner. We were the only customers left in the restaurant. The sound of rain intensified; the view through the window grew blurrier.

“Sorry, what?” Dake said.

“You want to know how I went from directing movies at the beginning of the Korean wave to running a chicken restaurant at the edge of K-town?” Mr. Kang asked again, thunderously.

“Um . . . the chicken is really good,” Eileen said timidly.

He slapped his thighs. “You’re absolutely right! My fried chicken is in-CREDIBLE! The best in LA! You won’t find better! So. You want to know the secret? You wanna know how I got here?”

He abruptly picked up the tray with our styrofoam container on it. The chicken had been picked clean, only the bones were left.

“Let’s go in the back,” he said, and we followed.

The back of the restaurant was a supply room. Next to a monumental steel fridge there was another door. Mr. Kang opened it, and instead of the door leading to a plumbing closet or private bathroom, it led into a movie theater.

Mr. Kang shuffled around while we clumped together at the entryway. The theater had a soft red carpet, a single leather reclining chair, a ghostly white screen that covered an entire wall, a projector mounted across from it. He turned on the projector, which whirred alive and beamed a blue light onto the screen.

“Sit down,” he boomed. “You don’t want to watch the movie standing up. You want beer? I’ll get you more. On the house.”

Dake looked at me; I looked back and shrugged. Jessica raised her eyebrows. “Not for me,” she said delicately.

“That would be great,” I said over her, annoyed. “Thanks.”

Brass music played from a speaker installed in some upper corner. Kang Original Productions flashed on the screen. “I have lived an ordinary life,” Mr. Kang said, but the voice came from the speakers. It was a voice-over, his own. The voice faded. The sound stopped. The screen cut to a student sitting at a window in a classroom full of children in dark uniforms. He was young, a boy with a blunt nose and curly hair. Mr. Kang?

The real Mr. Kang reappeared, shoving a cold can into my hand. I startled. Up close, his face was haunted and bluish under the light of the projector.

“Sit down, kids,” he grunted. He sank into the recliner. The rest of us found our way to the floor.

In front of us, the setting of Mr. Kang’s life — if this was his life — spun out on the reel. The camera panned across a landscape. We saw a soggy town, surrounded by hills, which the boy frequently looked beyond, as though longing to escape. His mother, a hairdresser, a woman of constant sighs, sweeping up black scraps of hair from the floor. His father, behind the flickering sign of a pawnshop, sat at a counter in a room filled with the detritus of once-loved items. Lighting played in advanced, subtle ways: shadows articulated into sheaths of cut hair, soft darkness resolved into unfurnished rooms in the shade of gloomy hills. Had he done this all by himself? A piano, startlingly clear, played four chords in a minor progression. The lens settled again on the student, the young Kang.

The boy Kang passed through school. He was a solitary child, silent around classmates, bored at home. After class, he read movie magazines and browsed the DVD rental store. Then college came. He went to Seoul. He attended parties, smoked cigarettes, learned how to get drunk. Kissed a girl at one party, lost his virginity at another. At the university film club, he met an upperclassman who liked him, treated him to a dinner out. The upperclassman brought his girlfriend, also in the film club, a pretty girl with long, silky black hair. She started hanging out with Kang occasionally, complaining about something her boyfriend had said, and let him put a hand on her shoulder while she teared up.

In the evenings, the boy Kang worked at an Internet cafe where drunk patrons pressed in on him with haunted faces. He wrote movie reviews for a small-time paper, saved up enough to get his own camera. One day, he was working at the Internet cafe, trying to write his script while manning the desk. A client came in, a tall man in a black peacoat, with amazing amounts of gel in his hair. The man looked around. He asked about rates. He sat down at one of the computers, clicked around for a bit, and came back. Asked Kang what he was working on.

“You want to make movies?” the client asked. “What’s your story about?”

He pulled up a folding chair and listened to the script idea. The man offered some pointers, gave some advice on structuring scenes, then the boy Kang realized who he was. “You’re Park Myungjae,” he said, naming the famous director of one of the year’s most popular indie films, which had even been shown at Cannes. It was a big deal for a Korean director’s films to be shown at Cannes, and he had been the pride of the nation.

The famous director began telling Kang his own story. He said that when he was young, his parents had a family friend who came over often, whom he called “uncle.” “Uncle” was a rich man, a singer, with a beautiful bass voice, powerful, rich, full of intimations of grandeur: the grandeur of life, of love, of country and patriotism and religion and God. Nobles, prime ministers, and presidents sought to have him sing for them. The broken-hearted gave him lyrics to sing to their beloveds. It was said that at some funerals, his voice could briefly bring back the souls of the dead.

One night, when it was only Park and this “uncle” sitting together, the “uncle” drunk on wine, he started telling young Park that he had grown up with a great knack for imitation. He was talented at mimicking the sounds, mannerisms, quirks of his peers. Sometimes he made people laugh; sometimes he made people angry.

He was especially good at mimicking voices. If his face wasn’t visible, he could easily fool others into believing that he was someone else: a parent, a teacher, a celebrity. He discovered he could use his talents by playing pranks on the phone, pretending to be other people. “I’m the secretary at your husband’s law firm,” he might whisper, or “I’m the janitor, I saw the vice president come in the other night . . .” Eventually his community turned against him, suspicion spread through all his friends, no one could trust what their lover or father or friends had said or not said.

When he grew up, the “uncle” continued, he left his small hometown and moved to the big city. He did the usual things to get by — waiting tables, construction work, a little thieving, a little lying. Then someone approached him. A rich man, not so far in age from him, but a different class, the son of a wealthy family. He wanted the young man to use his talent of imitation and talk to a woman over the phone. One of his lovers. In fact, the rich man had a multitude of lovers, both men and women, and he hired the young man to stay on the phone with them, murmuring sweet nothings to keep them in check.

The mimic spent hours on the phone, soothing the lovers with honeyed messages to keep them from finding out about each other, to make himself available to them when the rich man wasn’t. It was his full-time job. He would let himself into the rich man’s home and cradle the phone to his ear, twining the wire around his finger as he talked, hours and hours of talking while lounging in those opulent rooms. And the longer he spent with this man’s voice, this man’s identity, the more he loved being him. He loved the deep voice he used, the melodic tones, the lovers sighing on the phone. And sometimes, in another room far away in the house, he would hear the rich man singing in his beautiful bass voice . . .

“And then?” the young Park asked.

“The rich man died not long after that,” the “uncle” stated. “Totally unexpectedly. And I became a singer.”

Later, when Park asked his parents if they knew about the singer’s story and where he came from, they laughed at his wild imagination. The “uncle” never spoke of it again; Park began to doubt he ever had heard this story. He watched carefully, but the singer never slipped up, the voice he had in front of the family seemed so wholly his own, he was so confident and in control of it, the voice occupied his lungs and throat so naturally, as though perfectly molded.

And Park started to wonder if there really ever had been a rich man, a rich man with a beautiful voice who had mysteriously died . . .

His whole career, Park Myungjae told Kang in the Internet cafe, he had been haunted by this family friend’s story, which he wasn’t even sure if he had really heard, or if he had dreamed it up. The uncertainty dogged him. He distanced himself from his family and cut off ties with his past. All his movies were stories of slipping identities; his films were famous for his moody, saturated style, which evoked the surreal logic of dreams.

The director left the Internet cafe. Kang grew older. He went on to work jobs in small offices with red-faced bosses, drink heavily in barbecue restaurants, make short films on the side, and scrape together enough money for his first full-length film, five years later. He cast the girl with shiny hair as the lead. She was still dating the same boyfriend. Kang’s first feature was screened in small local festivals and panned everywhere.

The years passed, Kang was thirty-two, no longer a boy. He pitched another script. He got together a skeleton crew and the same girl. He wanted to film a cerebral, intellectual erotic thriller. Two people in a room, a lot of raw dialogue. The girl, married by now, agreed. The actor he had chosen was an everyman, could be anyone, could be Kang.

Kang recalled Park Myungjae, the famous director he’d met in the Internet cafe, the story of the family friend, the usurped voice, the telephone, the lovers. Kang’s film made extensive use of voices, darkness, husky whispers over phone lines. One night, he called the girl to the set alone. He was waiting in the director’s chair. The set was a cheap apartment they had rented for two weeks. The shiny-haired girl, now not really a girl anymore, knew what he finally wanted to claim. They had sex, the camera off the entire time. “How is your marriage going?” he asked at the end. She snuggled close to him. “It’s going great,” she said sincerely. “My husband and I love each other so much.”

When the erotic thriller came out, Kang scanned newspapers and websites for reactions. There was only one review. The story, the critic said, was banal and predictable. Kang’s sophomore attempt showed no subtlety, vision, eye for framing, or originality, which his first film also did not possess. The review finished off by saying that the actress from both of Kang’s films was wooden and unconvincing.

The girl Kang had loved all those years had stopped speaking to him. The last thing she said was she had finally gotten pregnant.

Meanwhile, Park Myungjae, the famous director from the Internet cafe so many years ago, had gone on to make one more major film, critically lauded, completely different from any of his previous movies, a straightforward historical realist drama. Then he quietly died of a cancer he had told no one he had. Kang found the obituary in the newspaper at work.

He left the office early and went back to his apartment and started calling friends on the phone. College friends, coworkers, acquaintances, people he had met over the years. “How have you been?” he said. “Are you free tonight?” On the other side of the line, murmurs of surprise, soft demurrals, many calls that went unanswered. He went through his address book to call number after number, but there weren’t so many people on that list, and finally, he hung up, no one was around, that was it.

Kang went out to walk along a bridge overlooking the Han River. It was night. He contemplated the dark water. He thought of jumping in. He thought of the hills he’d escaped from. He lit a cigarette. He thought of Park, the famous director, and the family friend, the singer who may or may not have stolen someone else’s identity, may or may not have killed a wealthy man.

Kang finished the cigarette and walked until morning. He went back to his apartment, looked at his notebooks full of ideas, the half-finished scripts, the collection of DVDs he’d accumulated, all classics. He called in sick to work, spent a week in bed rewatching each DVD all the way through. Then he took them all on a bus to a remote countryside, three hours away, and found a field. In the field he covered the DVDs in gasoline and lit them all on fire.

On a piece of paper he wrote:

Youth! It will never come again. Youth! It will never come again. Youth! It will never come again. Youth! It will never come again. Youth! It will never come again.

He threw the paper onto the pile of burning DVDs. When he got back to his apartment, his boss had called to say he was fired. On TV, there was a cooking show teaching how to make fried chicken.

The amount of effort put into the thing was staggering. Almost obscene. The actors looked completely natural. The camerawork was so close-up on their faces it was claustrophobic. Sound came through crystal clear: the drip of water, the huffing exhaust of a bus. Dialogue — what there was of it — was spoken in quiet, almost mumbled tones. The movie spanned sets, scenes, locations over the decades. It must have cost a fortune to produce.

I twisted my neck to look up at Mr. Kang. On the enormous chair next to me, his wide face was like a stone’s.

“Is this . . .” Eileen hesitated. “Did you make this all yourself?”

“It’s really good,” Jessica piped up.

Mr. Kang shrugged. The projector was now showing only a black screen. He stood, turned everything off. Some warmth in the room faded. Without speaking, we knew it was time for us to leave.

Outside, the rain had turned into a light drizzle. The strip mall was quiet, the silence almost harsh. All the other stores had closed. We stood on the sidewalk like children, waiting for direction on what to do.

Mr. Kang flipped off the restaurant lights. The laminate chairs and shiny metal counter fell into shadows. He came out and locked the doors. Without his apron and bandanna, he looked like a much different man. Angrier? Kinder? I couldn’t say. Ignoring us, he started walking away. When he fished car keys out of his pocket, in the parking lot, the lights on an ordinary black Nissan Altima came on.

“Is there a title?” I blurted out to his back.

He stopped and turned. “No,” he said. “I’m waiting for someone to help me think of one.”

I remembered my phone in my pocket. I pulled it out to see a swarm of messages from Billy. Where ARE you? / Did you drop off the face of the earth? / It’s late, are you home yet should I still come over? / Okaaay, it’s late and I’m going to stay here, thanks for this really fucking excellent communication

A car pulled up — smooth and silver, a silken little Audi. Jessica waved. Henry stopped near the sidewalk, got out and stood next to me, and greeted us.

“Luna, it’s been a while,” he said, smiling at me. “I was worried about you all when Jessica texted me.”

“That crazy owner just left,” Jessica stage-whispered, jerking her chin to indicate the departing Nissan. “I seriously thought he was going to axe murder us . . .”

Eileen made a noise of agreement. “That video was so shitty. Do you think he makes his other customers watch it? No one wrote about this on Yelp.”

I looked at Jessica’s smug and scornful mouth and Eileen’s nervous face, lit by her phone as her fingers tapped quickly. I could feel Dake’s eyes on me from behind. He hadn’t said anything since we left the theater. I thought he might feel it too, the shared, gaping emotion the movie had aroused in me. I didn’t want to look at him, so intimate was this feeling.

“Anyone need a ride?” Henry asked affably.

“I’m good,” Eileen said. “I parked in the lot.”

“You should come with us,” Jessica said to me. “We’ll drop you off on the way.”

“Thanks,” I said. The prosaic conversation of the real world rubbed at my skin painfully. Henry smiled at me, a sudden warm pinprick, like the kindling of a lighter. Memories flashed through me, feelings rather than images. The confused high school kiss with Dake, the volatile crying jags over my DJ ex, the lackadaisical warmth of the photographer I’d dated in New York, my long-ago fight with my college best friend, Melissa. So many nights and so many feelings, so many times my heart felt gnawed raw as a bone.

Against the neon sign of Mr. Kang’s chicken restaurant, Jessica’s face looked baby-fresh and soft, not so different from when I first met her. How sad I’d been when we stopped talking, and now she was back. Our lives were turning into what lives they would be. Everyone was looking at me. On an old phone, I thought, a young man was whispering in the voices of other people. Youth, it would never come again. I stepped up, tilted my face, kissed Henry squarely on the mouth.

Excerpted from Let’s Go Let’s Go Let’s Go. Reprinted by permission of Tin House. Copyright © 2023 by Cleo Qian.

© Casper Yen

Cleo Qian is the author of the short-story collection Let’s Go Let’s Go Let’s Go, out in August from Tin House. Qian is a writer originally from Southern California. Her work has been published in or is forthcoming from ZYZZYVA, The Guardian, Shenandoah, Pleiades, and The Massachusetts Review and several other outlets. Let’s Go Let’s Go Let’s Go is her first book.

We’ll mail you a free copy of this month’s issue. Plus you’ll get full online access—including more than 50 years of archives.

Request a Free Issue