We use cookies to improve our services and remember your choices for future visits. For more information see our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

March: This Month in Sun History

A Look Back for Our 50th Year of Publication

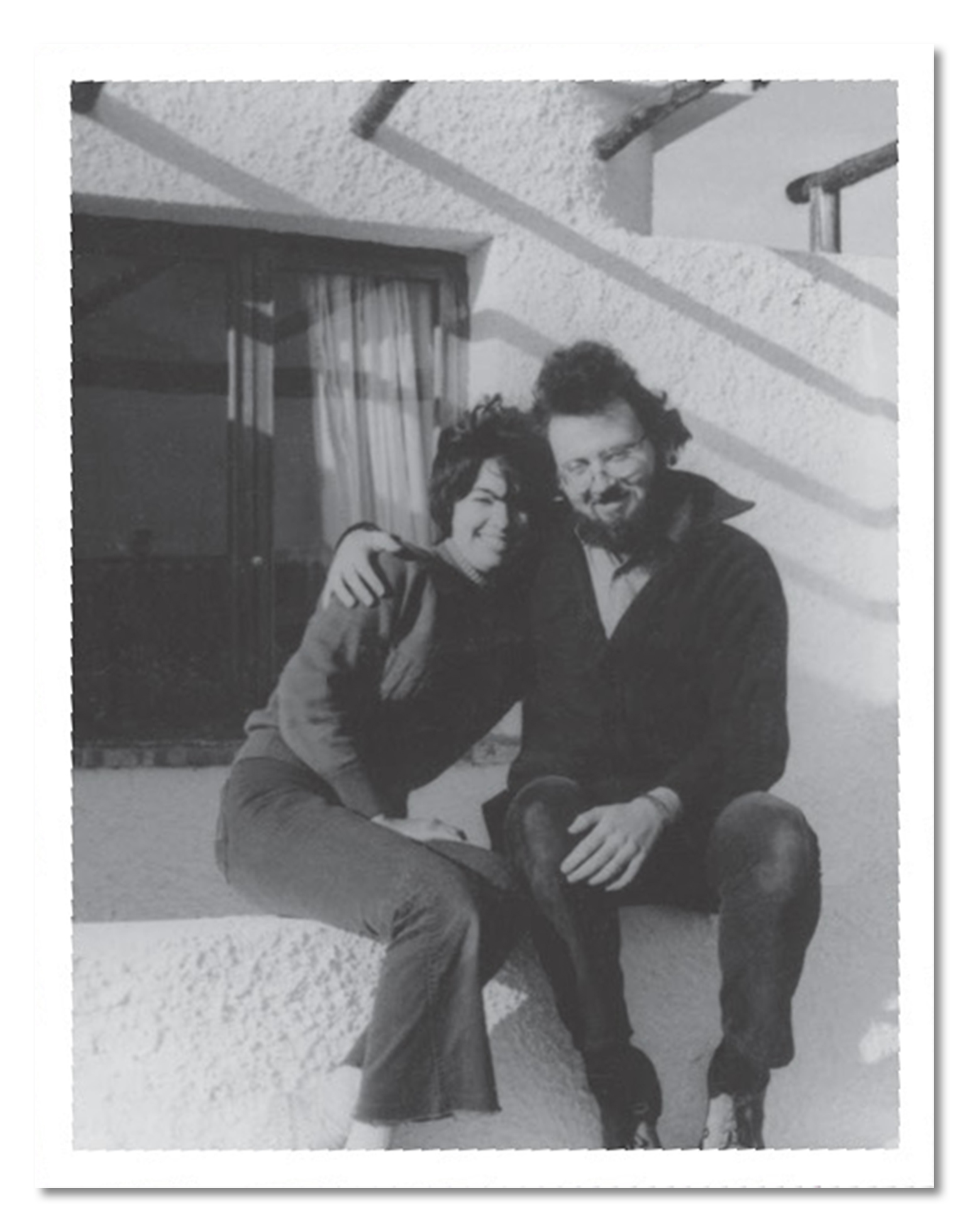

Sy Safransky with his first wife, Judy, in Spain.

Sitting with his first wife, Judy, and a friend on a sunny beach in Algeciras, Spain, Sy Safransky embarked on a spiritual journey that ultimately led him to create the magazine you now hold in your hand. In March 1970, for the first time, he placed a tab of LSD on his tongue. He was twenty-five years old. There were, of course, other steps between taking the powerful psychedelic and starting The Sun — spiritual teacher Ram Dass and the work of ex-Beatle John Lennon also played important roles in guiding Sy’s journey — but the drug changed the way he understood, well, everything.

It was no coincidence the experience took place on a beach. The previous summer he’d taken an ocean liner to Europe from the U.S. because he’d desired “the sense of making a great passage, of crossing an ocean, of journeying not just through time but through space. . . . I wanted a passage through the mind, a beginning, a birth — but of what, I couldn’t say.” He found the answer in that small tab of acid, which he’d been given by a German hippie who’d promised it would “make everything beautiful.” Sy carried it around for months, trying to decide whether he should take it or just throw it away. When he did, he realized “everything was alive and seamlessly joined, animated from within by something so joyous, impossibly, purely, speechlessly loving” that he couldn’t find the words to describe it.

“I never would have started The Sun were it not for LSD,” Sy admitted in 2014. “I don’t usually talk about that, because I think some readers might be dismayed to hear it. But I also believe it’s important to honor our teachers, regardless of the form they take, and for me LSD was an extraordinary teacher.”

We’ll mail you a free copy of this month’s issue. Plus you’ll get full online access—including more than 50 years of archives.

Request a Free Issue