We use cookies to improve our services and remember your choices for future visits. For more information see our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

All Families

Doug Crandell on Writing about Loved Ones

We’ve been publishing Doug Crandell in The Sun for twenty years now. I’ve been his editor that whole time, and I feel like I know him, even though we’ve met face-to-face only once. He writes with such honesty and openness, often about growing up in rural Indiana. His parents were “cash renters”—farmers who didn’t own a farm; they went from rental to rental, raising corn and soybeans and keeping only 20 to 30 percent of the profits. His mom and dad both worked at factories, too, and the family struggled to get by. All five kids helped out with the hard work on the farm. Sometimes there were accidents. I recently talked with Doug about how he navigated his family members’ responses to his essays about them. We also discussed writing as therapy, how Sun readers react to his work, and Halloween costumes in the seventies.

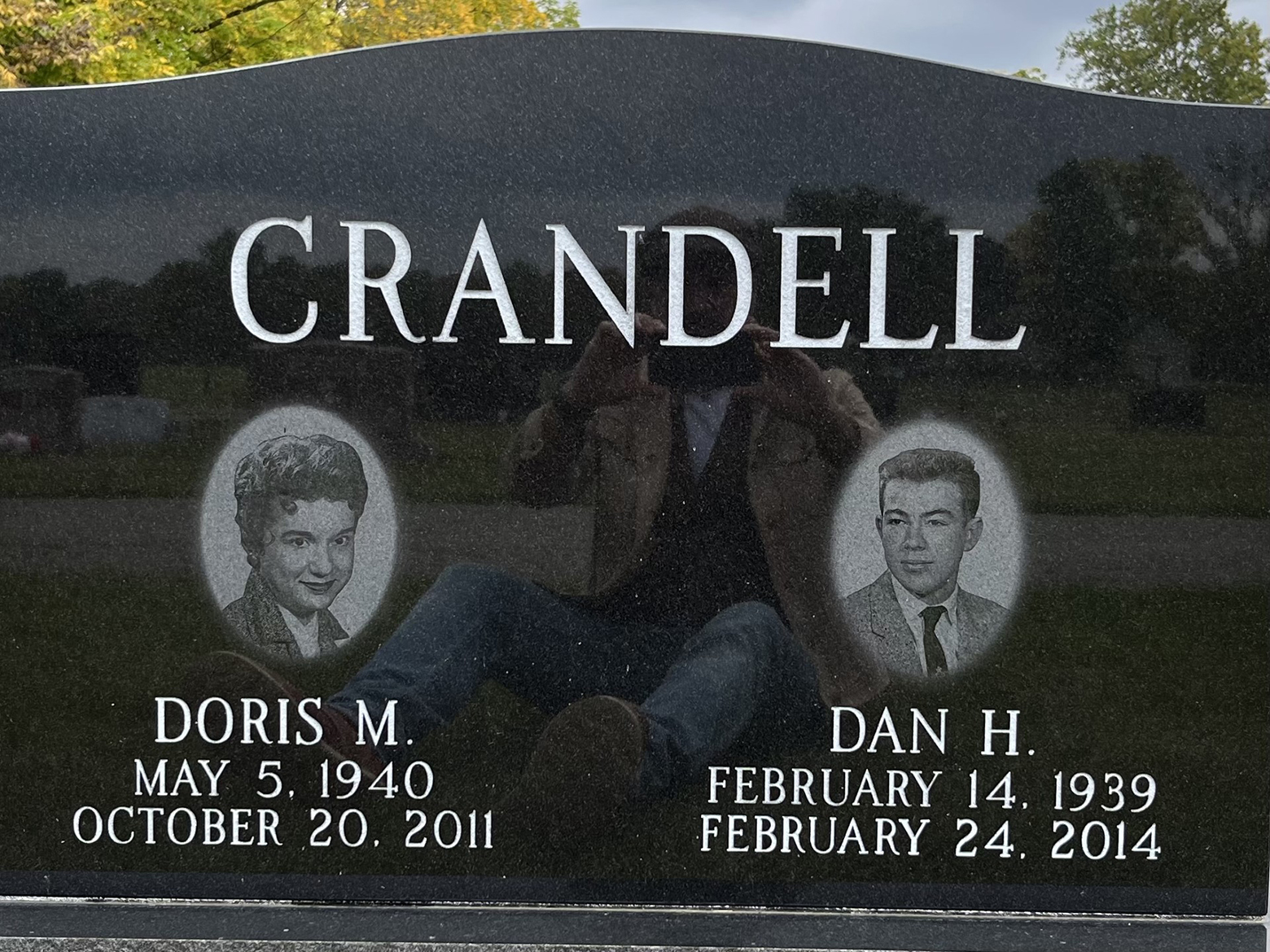

© Doug Crandell

Andrew Snee: The first essay of yours we published was about how you lost a finger in a corn auger as a boy.

Doug Crandell: That’s right. The doctor sewed it back on crooked. [Holds up his middle finger.] That’s what we used to call the “wicked bird.” [Laughs.]

Andrew: I think the next two pieces of yours that we published were both about your dad. And your essay in the December 2023 issue, “His Body of Work,” is a moving remembrance of him.

Doug: My folks have been gone now for ten and twelve years. “His Body of Work” is the first time I’ve written in The Sun about their passing. I wrote something back in 2015 or 2016, but Sy [Safransky, The Sun’s founder and editor] said, “Too soon.” This essay was probably the toughest thing I’ve ever written. By writing so much about my parents’ lives, I’d kind of been keeping them alive on the page, you know? But it just felt fitting, with The Sun’s fifty-year anniversary and my twenty years in the magazine, for me to lay them to rest.

Andrew: There’s a scene in the essay where your father expresses anger over some of the things you’ve written about him. It’s an issue we deal with a lot when authors write about their families, their marriages, their kids. We try to be careful and consider the people who are being written about, their feelings. So I was interested to hear that your dad wasn’t crazy about some of it.

Doug: Yeah, he was upset about my memoir The All-American Industrial Motel, which included three or four pieces that were first published in The Sun. My process for clearing things with my parents had mostly been to mail my mother the chapters of a book or a Sun essay—this is postal mail; my parents never used the computer my siblings and I bought them—and she would send the manuscripts back with large red marks on them. I’d say, “You can’t do that. You know, you can tell me how you feel, but you can’t take things out unless they’re inaccurate.”

My dad sidestepped all that. He was always a big reader, but of Westerns and the like. When I sent him the manuscript for The All-American Industrial Motel, he never responded. Then, after the book came out, he did sort of lightly threaten me and say, “If you weren’t my son, I’d drop you.” That was it.

I also published a true-crime book called Fear Came to Town, about the Santa Claus, Georgia, murders. That was the only book of mine my dad ever liked. Shortly after my mom passed, he called me and said he wanted some copies to give to the guys he worked with at the factory.

Andrew: What about your novels? Were they too close to home for him?

Doug: They’re literary novels. I mean, come on. He’s not going to read Hairdos of the Mildly Depressed. [Laughs.]

Andrew: How about your siblings? What’s their reaction been to your work?

Doug: I have two sisters and two brothers. I spend the most time with my brother Darren, and he would often say, “Why do you have to do this?” The other siblings just don’t pay it as much attention. One of my sisters has requested copies of all my books, but for the most part I think they’re confused that I want to write about such touchy topics: poverty, getting sick, the drug and alcohol abuse, my father’s affairs. And I admit those are difficult subjects. I’ve said to them, “You have every right to be upset with me, and I’m happy to talk anytime.”

My mom would sometimes call me on the phone, after I published something personal about our family, and say, “I hate you. I don’t want to talk to you again.” And that stung. But to her credit, she rose above the hurt feelings, and all four siblings have never disowned me. They still love me.

Andrew: My wife’s family is from southern Indiana, and she describes their attitude as “Let’s not talk about unpleasantness.”

Doug: That’s a great way to put it. In Indiana and in the South, where I’ve lived now for almost thirty years, you just don’t talk about some of those subjects—or, at least, you don’t address them in any significant way. I’m not sure I believe in writing as therapy, but I will say that getting to write about my family in the pages of your magazine has had some therapeutic value. When my parents passed, I was deeply sad, like we all would be, but I wasn’t holding on to any past hurts, because I’d gotten to write about my mom and dad so much.

Andrew: I worry we’re not doing your work justice by just talking about the parts your family didn’t like. I think there’s a tremendous fondness for them that comes through on the page.

Doug: Sometimes my siblings will say they found a part of something I wrote really beautiful. They all loved my essay “The Sister in Our Dreams,” about one of the two children my folks lost as infants. I think when I’ve written about us working together as a family, that can be affirming. They also liked the essay where my mom made a Jaws-themed haunted house for my elementary school’s Halloween carnival.

Andrew: I remember that one: “Not Suitable for Children.” It’s a good example of the humor and lightness in your writing. It reminded me of my mom, who sewed a lot of Halloween costumes in the seventies. They were all initially sewn for my older brother, who was a big kid, and I was not, so I was often wearing those costumes at an older age than he did. I had to wear a big pink pig costume long past the age when it was cute.

Doug: I’d love to see a picture of that. [Laughs.] I don’t know if you’ve read any of Douglas Coupland’s novels, but one is titled All Families Are Psychotic. Everybody’s family, whether they have money or are leaders in their community or not, they struggle. It’s normal. There’s something reassuring about acknowledging that. The December issue of The Sun has only been out five days, and I think I’ve gotten fifteen messages or emails about “His Body of Work.” I’m kind of shocked by it. I don’t know what to attribute it to.

Andrew: I think it’s like you’re saying about everybody’s family having issues. We all know these things happen, and we suspect that they happen to other people, too. When readers encounter somebody writing openly and honestly about it, they respond.

Doug: I’m consistently amazed by The Sun’s readers. They’re just wonderful people.

I work in human services, and maybe fifteen years ago I was employed by a nonprofit outside of Atlanta. The chief financial officer and I didn’t get along. I couldn’t stand her, and she couldn’t stand me. We would avoid each other in the office. One morning we were both in the same space, and I’m just not somebody who can ignore another person, even if I don’t like them. So I said hello to her. She didn’t say anything back at first. Then she asked, “Do you publish in The Sun magazine?” I felt punched in the gut. I never would have thought this CFO was a Sun subscriber. I said yes, and our relationship completely changed. We still email all the time. We’re probably as close as a former CFO and employee can be. It’s pretty disturbing to me that I was able to miss all the good things about her for a long time.

It sounds cliché, but your magazine truly is a community. You create the power of community through what you publish.

We’ll mail you a free copy of this month’s issue. Plus you’ll get full online access—including more than 50 years of archives.

Request a Free Issue