We use cookies to improve our services and remember your choices for future visits. For more information see our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

An American Disease

Anders Carlson-Wee on Dumpster Diving in a Culture of Waste

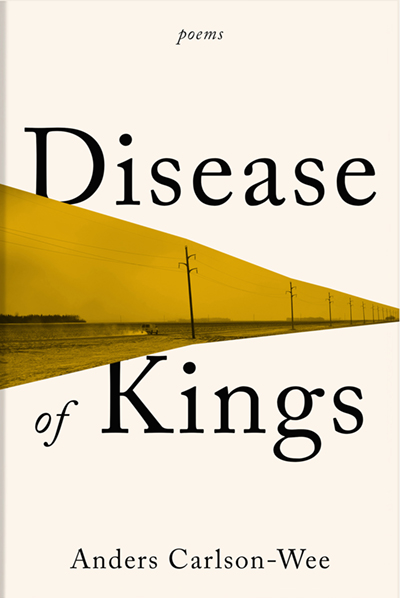

For ten years Anders Carlson-Wee got almost everything he needed from the trash: food, clothes, furniture, lamps. “The second I was done with high school, I knew I wanted to go into the arts,” he told me. “That meant I had to figure out how to be self-reliant and live off almost no money.” Living for free required more work than one might expect — he had to dumpster dive according to a strict schedule, sometimes making multiple runs per day (or night) to intercept certain products, as well as clean and store what he collected — but it also gave him the time to let his mind “wander where it wanted to go creatively.” He wrote about his experiences in his essay “The Salmonella Special,” which appears in our November issue, and in his new poetry collection, Disease of Kings, released this October by W.W. Norton. When we spoke over Zoom, I asked him to tell me more about this lifestyle. We talked about capitalism, loneliness, freedom, and one of the greatest hauls of his dumpster-diving career.

In addition to Disease of Kings, Anders has published two other books of poetry: The Low Passions, a New York Public Library Book Group selection, and Dynamite. Though he now makes a living as a writer, he still dumpster dives around his home in LA.

ANDERS CARLSON-WEE

Nancy Holochwost: You’ve written pretty extensively about the years you lived off items that you reclaimed from the trash. What do you want readers to take from these stories?

Anders Carlson-Wee: I found that period of my life to be a profoundly creative experience. Any material item that I saw, I would think of three or four uses for it and ways it could be reused multiple times. That mindset fueled my writing as well, and it’s something that’s stayed with me: How can language accomplish three or four things at once? How can you reuse language, and how does it become new each time? There’s a lot of overlap between dumpster diving and writing: writers sift through language in the same way you sift through a pile of trash. I don’t want readers to get one particular message from my writing about dumpster diving, but I certainly see Disease of Kings as engaging with the environmental issues of our time and the huge amount of waste in the U.S. Part of what the collection conveys is that, in this country, if you live off trash, you’re not eating pizza crusts; the speaker is dumpster diving for huge quantities of the best-quality food that you could ever buy. I hope the book contributes to the conversation about our ecological footprint, and though I would never presume to tell people how to live, I hope reading the collection will get people to think about how they might alter their lives on their own terms. But the book is not prescriptive; I see the poems as implicitly bringing up those questions.

Nancy: Living off trashed items had several effects on your life: it saved you money; it gave you time to pursue writing; it allowed you to avoid participating in consumer culture. How did those interplay for you?

Anders: Getting outside of consumer culture in our country is a tricky matter. My lifestyle meant that I didn’t go anyplace that had a sticker price — restaurants, cafes, bars, concerts — and that meant I was exempt from a lot of what social life looks like in the U.S. In a capitalist culture, to be a social person often means to pay for things. My social life was extremely limited, down to a very small group of people who wanted to live like I did. But while living that way came with its costs, it also allowed me to commit to reading and writing, which was what I was after. That’s a conflict Disease of Kings grapples with. We follow the speaker chasing this certain sense of freedom: freedom from responsibilities; freedom from the workaday life. In a way he obtains that freedom and feels some benefits from it. Yet he also finds himself in a state of desolation, loneliness, and confusion, and he’s ashamed when he needs handouts from his parents. There are a lot of complications in that longing for freedom.

Nancy: In “The Salmonella Special,” you write about the cultural taboo of trash: a book on someone’s shelf is innocuous; put that same book in a garbage can and “almost no one will touch it.” How embedded do you think that perception is in our society?

Anders: I think it’s deeply embedded. I don’t know if you remember the Seinfeld episode where George Costanza takes a bite of an éclair that he’s taken out of a garbage can in the kitchen. The joke is about the definition of when the éclair becomes trash: Was it below the rim of the can? Was it touching other garbage? Once something has been put in a trash can or dumpster, it gets a label, and people don’t want to be associated with that label. That is tough to change, but I think there are ways to change it, and probably the biggest one is not to let all that food go in the trash in the first place. I’ve talked to a lot of grocery-store employees — as a dumpster diver, you end up encountering them. When I interviewed workers for a documentary film about dumpster diving I made when I was in college, I would ask them to walk me through the waste system at their store: Why do certain things get thrown away? There were many reasons. If packaging gets damaged, even if there’s no puncture or safety concern, the item is thrown out for cosmetic concerns. Sometimes shoppers abandon their carts, and the food from the refrigerated and freezer sections can’t be reshelved. The employees I spoke to told me lots of food could be saved if stores were willing to hire one or two people to determine what could be salvaged and donated to food banks and other places, but stores consider that too much of an expense. To keep their costs low, they basically chuck anything that even approaches the label of trash, and that ends up creating a huge amount of waste.

Nancy: In the essay you mention your grandfather’s “bagel ministry,” in which he delivered two-day-old bagels that would have been discarded to seminary students. Did your family contribute to your choice of lifestyle?

Anders: Absolutely. Disease of Kings is dedicated to my grandpa, Roald Carlson, largely because of how much he guided me toward this way of living. He was the child of missionaries and grew up with very little money during the Depression; he claimed he didn’t own shoes until he was fifteen. He was an extremely frugal person, both for practical and moral reasons. The idea of wasting food was unconscionable to him. You had to clean your plate; if anything was left over, you had to eat it the next day. One of the first gifts I remember getting from him was a fan that he’d found in a dumpster: he knew my childhood bedroom got very hot, so he took the fan home, fixed the wiring, and gave it to me. From him I learned to be self-reliant, to creatively reuse products, and to think of material goods as having great value, even spiritual value. The ideas he passed on to me were probably the biggest influences on my decision to live the way I did — though I would say, compared to my grandpa’s, my motives were less moral and more selfish. I really did just want to buy myself a lot of free time. [Laughs.] But I was always interested in the morality, too.

Nancy: Your friend and roommate North, who appears in the essay and in several poems in Disease of Kings, is a larger-than-life character; you admire him, but you two also sometimes clash over the lengths he’ll go to live for free. What was it like to have him as your dumpster-diving partner?

Anders: North is more alive in the moment than I am. He has more energy, and he’s more excited and more reactive to the situation. If he finds ice cream in the dumpster, he starts eating it right then. My personality is much more calculating, and I have a scarcity mindset that makes me afraid of running out of food. If the two of us took in a big haul while dumpster diving, North would be thinking about how to use it to make a huge dinner that night or breakfast the next morning, and I’d be planning how long it could last if we portioned it out. I emphasize those contrasting impulses both in the essay and in Disease of Kings because I thought it was interesting for us to share this lifestyle, yet have extremely different mindsets about it. To me, my mindset is more troubled and a worse way to think. I admire North’s approach, which is to celebrate what you find and enjoy it right away, because you trust you’re going to find more. And the reality of that lifestyle is you always do find more.

Nancy: The phrase “disease of kings” comes from a description of gout, a condition historically associated with wealth, which North contracted by eating too much scavenged red meat. What comment did you want the title to make?

Anders: There’s certainly irony in the idea that a couple of twenty-something scavengers can eat so well from the trash that they could have a disease that comes from overindulgence. For me the title expands beyond gout and speaks to the idea of the disease of the U.S.: the disease of consumption, capitalism, and overabundance, which my characters are inextricably caught in, even as they try to escape it. I think it also speaks to the loneliness of the dumpster-diving lifestyle. The men in the poems are living “like kings,” but they’re also profoundly isolated, which is something that I imagine a king experiences: the loneliness of being in a role that no one else shares.

Nancy: What made you start paying for food again, and how did that affect your life?

Anders: I’d been living without buying any products for most of a decade, into my late twenties. I had my expenses down to about $3,000 a year, which was basically just rent and a little extra for emergencies. That was working for me, but I was starting to see that it was going to be hard to maintain forever. I also wanted to find a way to push my writing to the next level. So I decided to apply to fully funded MFA programs, which I saw as a chance to move my writing forward while receiving financial support. The school I attended paid me a stipend that was ten times more money than I was used to living on. My reaction was not to spend more, but to save it all. When I finished the two-year program, I had enough money to support my lifestyle for another ten years. Because of that security I slowly started allowing myself some indulgences, like going to a concert or eating at a restaurant once in a while. But that was actually a painful experience, because I’d been living so frugally for so long. Every time I spent money on something that by my standards was an extravagance, I’d be thinking, I know how to do without this. It’s hard to turn off that mindset.

Nancy: Did you ever experience serious consequences from scavenging, such as illness or trouble with the authorities?

Anders: I’ve been asked this question quite a bit, because a lot of people want to know if I’ve gotten sick from eating all that trash. My answer, which feels important to share, is that I’ve never gotten sick from dumpster diving, but I have gotten food poisoning multiple times from restaurants. That may seem strange, but I think you pay more attention to the state of the food in a dumpster than you do at a restaurant or a grocery store. Your senses are on high alert: How does this smell? How does it look? Does it seem safe? As far as getting in trouble with the law, I got in more trouble as a skater when I was growing up. When I have interacted with the authorities while dumpster diving, their attitude has always been “Just leave it how you found it. Leave no trace.” I’ve been pretty lucky in that regard.

Nancy: What’s the craziest thing you ever found while dumpster diving?

Anders: One night a couple of friends and I found five five-gallon buckets full of chocolate bars in the dumpster outside of Theo Chocolate in Seattle, which makes high-end, organic chocolate. (Unfortunately I just heard from a friend that this dumpster is closing down.) There were all kinds of flavors: coconut, cayenne, sea salt and almond, plain dark chocolate. We took home so much that we spent the whole next year making desserts and fondue and giving huge stacks of bars away to friends. I went so far as to take a tour of the Theo Chocolate factory so that I could casually ask why they would throw out their products. They told me their brand relies on precise flavor notes, so if they made a batch of, say, dark chocolate sea salt, and it was a little too salty or not quite salty enough, they’d toss it. There ended up being a ridiculous amount of chocolate waste, which I benefited from greatly.

Anders Carlson-Wee’s new poetry collection, Disease of Kings, was released this October by W.W. Norton.

We’ll mail you a free copy of this month’s issue. Plus you’ll get full online access—including more than 50 years of archives.

Request a Free Issue