We use cookies to improve our services and remember your choices for future visits. For more information see our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

The Challenges—and Joys—of Pregnancy

Selections from the Archive

Lucy Tan’s “ Falling Action in Hoboken,” from our February issue, is the story of a young woman who begins dating a man she meets at a bar, then unexpectedly finds herself pregnant. The unplanned pregnancy bumps up against her imperfect relationship with Matt, her vocation as a theater reviewer, and the unencumbered life she had envisioned for herself. The narrator describes her hesitations about carrying the pregnancy to term: “I think about the word womb a lot, about how it sounds like a cross between wound and tomb. I don’t want to be a mother. I am not qualified to be a mother.”

Below is a selection of pieces from our archive that explore the challenges—and joys—women may face when discovering they’re pregnant.

Take care and read well,

Derek Askey, Associate Editor

Gillian Kendall’s thoroughgoing interview with political columnist and reproductive-rights activist Katha Pollitt appeared in our December 2015 issue. In it Pollitt explores the political, social, and economic aspects of the battle over reproductive rights in the US.

I recommend clicking that MORE LETTERS button at the bottom of the interview—we received a lot of them.

© Kori Teague

It’s Her Choice

Katha Pollitt on the Struggle over Abortion Rights

Abortion became a politically charged issue only after it was connected to women’s independence. As long as abortion was about saving a daughter from shame or helping a woman who was exhausted from having too many children, it was accepted (though probably not talked about much), but when women began marrying later and postponing having children in order to become more politically and socially active, then it was considered a problem.

It’s Her Choice: Correspondence

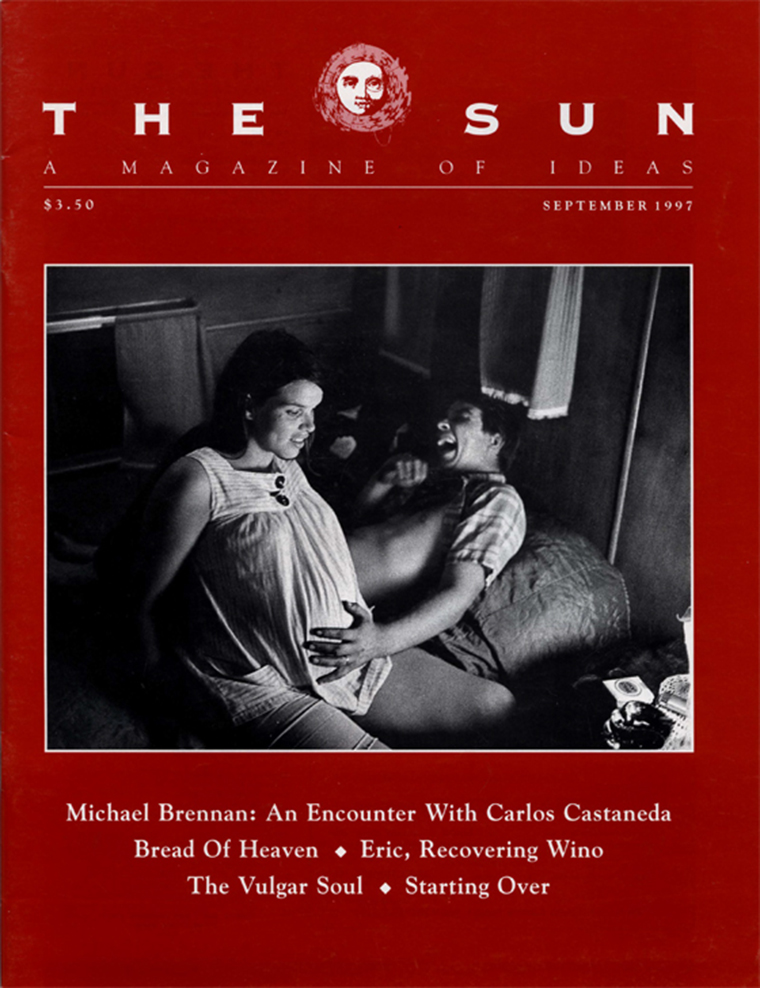

December 2015We’ve published plenty of photos that deal with pregnancy, but the cover of our September 1997 issue, taken by Gordon Baer, stands out. Maybe it’s the expression on the man’s face, which looks either pained or ecstatic. Maybe it’s the pack of Lucky Strikes on the nightstand. Maybe it’s all of it.

The photo is part of a series Baer took of Karen Petty Lewis. We printed other images from it the following December.

Lots of pieces talk about the challenges of going into labor and giving birth, but few do it with such a keen attention to the bodily comedy that it can be as Lisa Taddeo’s essay “Labor Day,” which we published in our November 2015 issue. “The other day she pushed a couple of fingers up inside me,” Taddeo writes of one of her nurses, “and waggled them from side to side as if she were ringing a dinner bell.” But what’s always stuck with me has been the joy Taddeo describes, too: “She is brought to me. Her mouth, her smell, her new skin—everything is perfect. She has dark hair and cobalt eyes that belong to some distant planet.”

This piece is a little unusual for The Sun: with it we included a photo of the author’s actual newborn daughter in the delivery room, taken by Taddeo’s husband, Jackson.

The author’s daughter, moments after birth.

© Jackson Waite

Labor Day

Suddenly, there it is: the cry not of a baby, but of my baby.

I wanted a little girl—to feel closer to my parents, to know how they felt having me—and now I’ve got one, or I’m about to get one. Please, God, just let her live long enough that I can kiss her feet.

You read about the love, how big it will be.

Jesus.

November 2015The personal, as they say, is political. That’s evident in this poem by Cedar Koons, which appeared in our June 1988 issue. Koons describes having an abortion and being driven there by her Catholic father, “just like he took me to confession / other Friday evenings, to tell my sins.”

Leaving Home

Outside the pink bungalow in Pleasure Ridge Park, two men sat in a Thunderbird, engine running. My father said they watched the house the whole time. In the living room, the tv was on. I sat on a sofa against a green afghan until she was ready for me. Her husband drank a beer, told me not to touch the shivering chihuahua. “She’s got a mean bite,” he said. Aunt Wanda’s husband found this woman. His truck drivers recommended her. My father, a good Catholic, drove me there, just like he took me to confession other Friday evenings, to tell my sins. In her bedroom, pictures of grandchildren cluttered the dresser, white stockings hung on a wooden rack above white shoes newly polished. She had me lie on the double bed. Opening my legs for her wasn’t easy. She was hunched and burnt-looking. Her whole face puckered toward her mouth. She spoke with words like “dirty shame” while she gave her absolution— a small, white cloth inserted into my womb. I wanted it to hurt. It didn’t at first, not even the needle she pushed into my thigh while I watched my hand curl and uncurl the pink chenille. The first blood came before dawn. My father went to work. My mother watched tv. I lay upstairs in my room and thought of college as rhythmic pains came. I turned my crucifix to the wall and soaked the sheets. Just after lunch I passed the cloth, some clots, some flesh, then bundled it all in a clean towel and lay on the yellow bathroom rug. I will go away from here, I sang to myself, I will never come back, I will never come back.

Dulcie Leimbach’s engrossing short story about the initial days after the narrator gives birth to her daughter appeared in our November 2000 issue. The narrator describes the challenges of caring for her son, Paddy, both before and after the birth; the distance she feels from her artist husband, Chas; and the uncaring nurses, who are dismissive of her pain. More than anything, though, she makes the reader feel just how tired she is.

© Aaron Serafino

Any Comments or Questions?

Girlie slid out like a hot buttered noodle on that Indian-summer night in October—her father’s birthday, in fact. Chas was in the birthing room, standing next to my hospital bed. A few minutes before, he’d been complaining that his legs hurt and he needed to sit down. The midwife cleaned Girlie off before presenting her, blue-ribbon style, to us, and I thought about how one chapter in my life was ending and a new one was beginning, whether I liked it or not.

November 2000In her poem “June 1954,” published in our October 1997 issue, Mary-Beth O’Shea-Noonan thinks about her own birth and of the two people who brought her into the world. “All salty, fishy human need— / I swam into the dark / and heavy egg of my mother.” Holy smokes!

June 1954

I was conceived in a shack by the sea, its shingles bleached and beaten nickel gray. There were waves that day washing over the foundations of the old saltworks. My father told me this, his eyes the blue of a still inlet after rain, and I can imagine such a thing. My rising like a cry from my father’s throat, breaking free of his longing and swimming, all head and eager tail, all salty, fishy human need— I swim into the dark and heavy egg of my mother. This is me. My mother’s eyes were green as ocean weeds, but I did not, of course, see them open wide, did not see the pupils swell deep and black as tidal pools. A blade of sea grass swirled oblivious to the wind heavy with the rank sulfur scent of low tide.

We’ll mail you a free copy of this month’s issue. Plus you’ll get full online access—including more than 50 years of archives.

Request a Free Issue