We use cookies to improve our services and remember your choices for future visits. For more information see our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

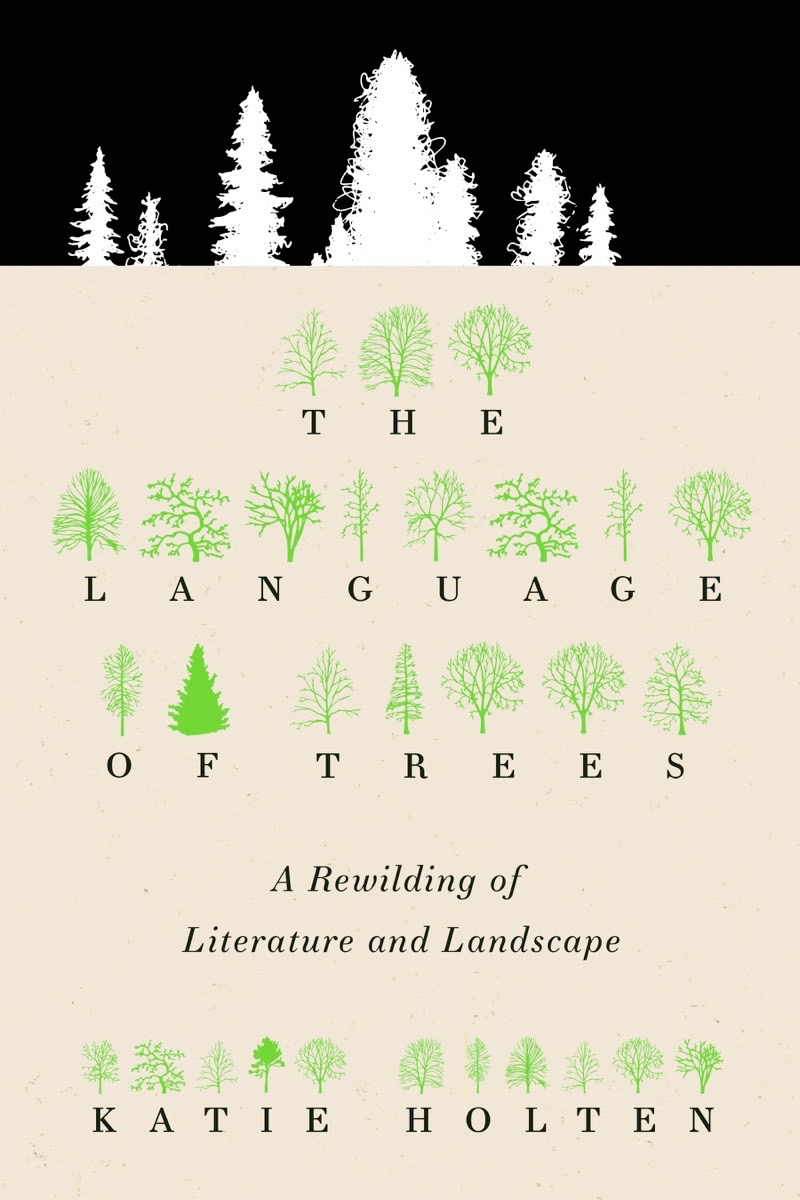

Introduction to The Language of Trees

A Rewilding of Literature and Landscape

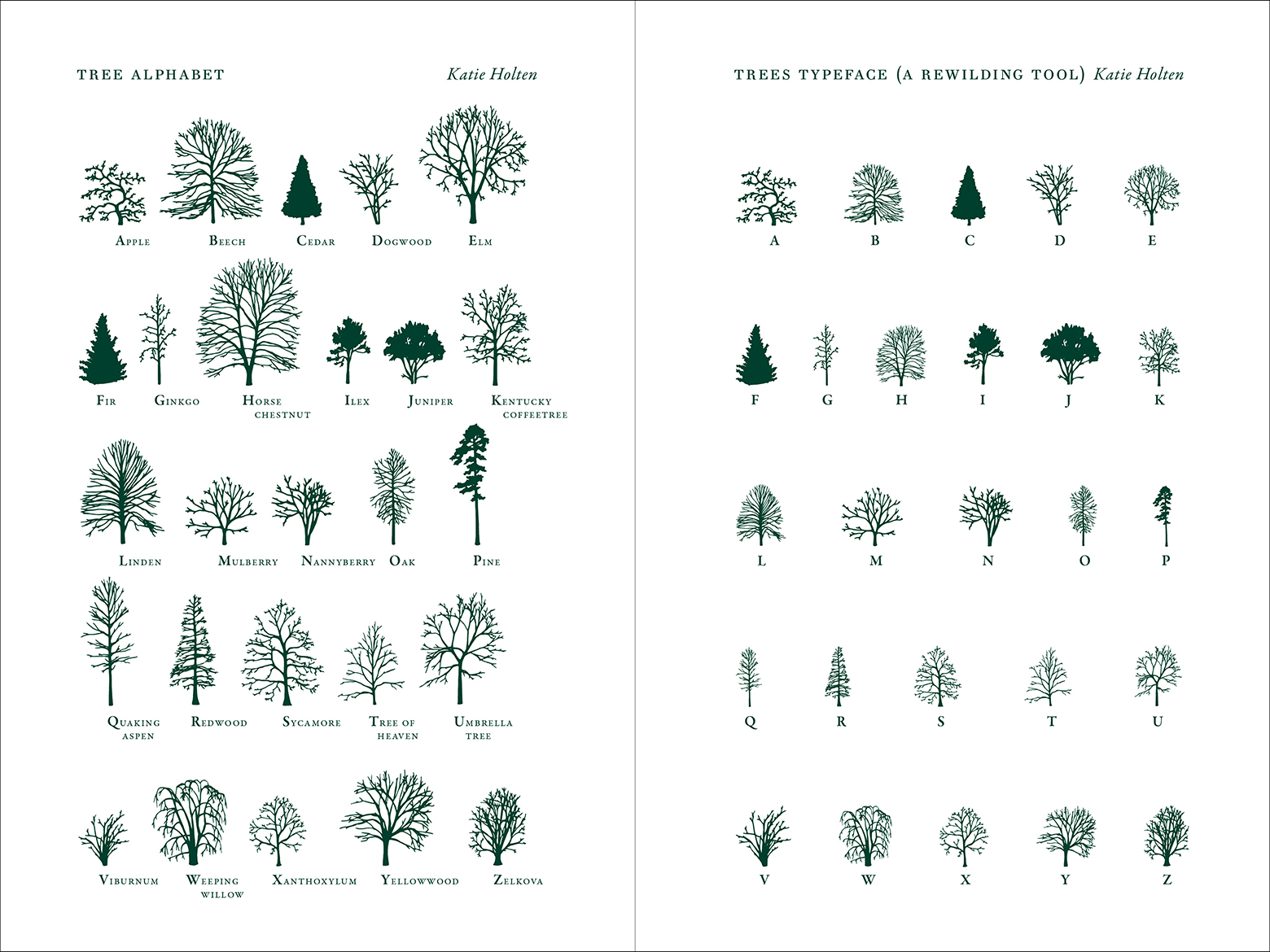

In this new collection from Tin House, Irish artist and editor Katie Holten gathers writing in celebration of the natural world from more than fifty contributors including Ursula K. Le Guin, Ada Limón, Robert Macfarlane, Zadie Smith, Radiohead, Aimee Nezhukumatathil, James Gleick, Elizabeth Kolbert, Plato, and Robin Wall Kimmerer. Holten includes an illustrated version of each selection based on her tree alphabet.

We are pleased to share Ross Gay’s introduction to the book as an exclusive online excerpt. The Language of Trees is out today, April 4, 2023.

— Ed.

I sometimes think of making a book of all the trees I have loved. I would include the mulberry tree in the tiny woods between the school and the apartments where I grew up outside of Philadelphia, into which every June I’d squirrel to harvest berries; the chokecherry tree in Verndale, Minnesota, where my grandpa parked his hospital-green ’68 Chevy pickup, atop which I’d scoot to pull some fruit for the both of us; the redbud tree on Third Street that my partner, Stephanie, showed me, whose leaves, backlit late in the day, became a canopy of luminescent, blood-red hearts; the pear at the end of the block, a sale tree from a box store that produces the sweetest, most reliable fruit in town and is a local oasis for human, deer, possum, yellow jackets, and more; the giant sycamore with the fleshy, oceanic bark towering in the southeast corner of the graveyard, whose shade on hot days is about ten degrees cooler and so is a no-brainer gathering spot. And there’s that beech tree I met in Vermont on a night hike two summers back against whose smooth trunk I leaned my head. The beech’s breathing seemed to sync up with mine, or mine with the beech’s, and though I can’t say exactly what I was hearing or feeling, I know it was a language coursing between us.

The word beech, I was delighted to learn a few years back, is the Proto-Germanic antecedent for the English word book. The words for book in some other languages also derive from or overlap with the names of trees. I suspect part of that common root has to do with trees providing the material for books, but it is also the case that being in a library — I mean, the best libraries — can sometimes feel like being in a forest: a wild variety of plants from the canopy to the ground; all manner of life, some of it visible, most of it not; patches of dense shade; swaths of deckled light; clearings where a huge tree just fell and you can almost hear the turning beneath, toward the light. Just as being in the forest can sometimes feel like being in a library — where what maybe begins as an illegible and almost foreboding place (see every fairy tale) becomes, with time and guidance and patience and wonder, all these voices, all these stories. Oh, with wonder we say the trees have a language. There’s a language of trees.

We watch the light flickering across their leaves, or the wind blowing them into song. We see the squirrel peeking out from the porthole in the oak thirty feet up, or the yellow jackets entering and departing the withering branch that until this moment we would have called dead. And the bloom of fungus underneath. We enter the canopy and soften our eyes and see or hear or feel the thousand pollinators perusing the blooms. We reach down to pick up one from the constellation of persimmons glowing at our feet. The woodpecker and the chipmunk, the beetle and the worm. We notice the branches and all their reaching. We learn the root systems sometimes scribble through the earth far beyond their massive canopies, some of them for miles, entangling with other roots and life, knitting themselves to all this other life. Their own life made possible by being knitted, the trees seem to be trying to tell us, to all this other life. Except the trees never say other.

What the trees say, and how they say it, has never been as interesting to me as it is right now. Not only because, as you now know, I’m putting together a book of beloved trees; not only because I have been lucky enough to work with the community orchard in my town; not only because of that beech tree whispering to me in Vermont. The language of trees is so interesting to me because, whether or not we learn to understand it seems so obviously a matter of life or death. Our capacity and willingness to study the language of trees might incline us to be less brutal, less extractive. It might incline us to share, to collaborate. It might incline us to give shelter and make room. The language of trees might incline us to patience. To love. To gratitude.

Katie Holten’s tree alphabet.

Courtesy Tin House, reprinted from The Language of Trees by Katie Holten.

Which is precisely what I would call The Language of Trees: A Rewilding of Literature and Landscape — a gratitude. An immense, redwood gratitude. Sycamore gratitude. Aspen gratitude. Pawpaw gratitude. Not only for the gathering of wonderers and lovers of the arboreal that this new collection brings together. But gratitude also for the literal language of trees — a script made of different trees — by which this work is conveyed to us. Can I tell you how batshit beautiful I find this? How each piece, translated into this language of trees, each essay or poem or song becoming a forest or orchard, rattles me, flummoxes me, really, with how beautiful it is? Yes, I mean they are graphically beautiful; they are astonishingly beautiful to look at as pictures. But what moves me so deeply — by which I mean into the loam, my own roots reaching out to yours — is the listening and care, the devotion and curiosity by which this script of trees comes into being. The gratitude, I mean to say, by which the language of people becomes the language of trees. The gratitude by which this book turns us into trees.

For which gratitude, I am thankful.

— Ross Gay, 2023

Excerpted from The Language of Trees: A Rewilding of Literature and Landscape by Katie Holten. Published by permission of Tin House. Introduction copyright © 2023 by Ross Gay.

We’ll mail you a free copy of this month’s issue. Plus you’ll get full online access—including more than 50 years of archives.

Request a Free Issue