I’ll be the first to admit: We should have checked the weather. That was our bad.

Tommy was twenty-one, and I was twenty-two, when we decided to drive to Julian, California, for the weekend. We got to our campsite and set everything up well before dark. Then we leaned back in our chairs, drinks in hand, beside the blazing fire.

I felt the first drop hit my cheek just seconds before it began to pour. Tommy and I shrieked like gulls and made a beeline to our tent. Once inside, I zipped the entrance shut, but the rain fell with a fury. In no time water had seeped inside, flooding the floor.

Soaked and shivering, we lay on our backs and stared at the tent roof, which looked to be minutes from collapsing under the weight of the water. I expected Tommy to be angry or, at the very least, worried, but the bastard grabbed my hand, squeezed it, then started to laugh. His laughter—loud and full and contagious—lit something inside of me, and I laughed right along with him.

We got wicked colds and had to miss work on Monday, but I loved that Tommy chose to kiss me instead of complain and that, as we were packing up, he talked about the ways we could improve our next outing. If he could find humor in a hellish camping trip, I thought, we could get through anything together.

A.R.

San Diego, California

After a day of military maneuvers in the blistering desert heat, all I could think of was sleep. I was so tired I dozed off during dinner, only to jolt awake with a piece of cold stew in my mouth.

At evening roll call I stood at attention, eyes drooping. The officer assigning our two-hour nighttime patrol shifts told us that under no circumstance could we use flashlights when patrolling or to look for the tent of the next soldier on duty.

To my delight I got the first shift. Once it was over, I could sleep uninterrupted. I watched carefully where the soldier who would relieve me pitched his tent, then began my rounds.

As the sun set, though, the tents nearly disappeared into the darkness, and I became confused. When my shift ended, I stared at the rows of tents in a panic, with no clue which one belonged to my replacement. Afraid of waking the wrong soldier, I covered all the shifts that night. The next morning, while everyone else had breakfast, I slept, oblivious to whatever consequences the officer would impose.

Aryeh Sherman

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

On a summer vacation in Riva, Italy, in 1970, my parents, my children, and I were drawn out of our hotel by joyous shouting and oompah music. Trapeze artists in glittering outfits strutted down the street, followed by elephants lumbering along. A lion roared in protest from his cage. Clowns with white face paint and bright-red hair somersaulted or walked on their hands. Horseback riders were followed by a crew that scurried behind, cleaning up the droppings.

My kids pulled at my sleeve, begging to go to the circus. I assured them we could.

The next day in the big top, a man and woman entered the ring, both tattooed and dressed in black leather like Hells Angels. The woman set a basket to one side as the two of them pranced around. Then she pulled off her jacket and slacks—revealing a leotard and fishnets—and unhooked the barrettes holding up her hair. She cast a lascivious glance at the audience before reaching into the basket and raising high two thick, writhing snakes, each four or five feet long.

The woman set the snakes down, and while the circus band played Ravel’s Boléro, the serpents curled around the woman’s ankles, slithered around her calves, and angled up her thighs, approaching her you-know-what. I couldn’t help feeling a self-protective tightening of my own you-know-what.

I sat transfixed while the musicians increased the tempo, As the band hit a crescendo, she grabbed each snake, held them aloft again, then unceremoniously plunked them back in their basket and exited the ring.

A clown car tooted into the ring, spewing first one, then two, and then a dozen clowns, who paraded about and handed balloons to the children. I breathed a sigh of relief.

Judith Gussmann

Berkeley, California

When I was twenty-two, I biked across the country with a college friend. Two women eager to see America, we camped wherever we ended up: fallow fields, state parks, the front yards of friendly folks we met.

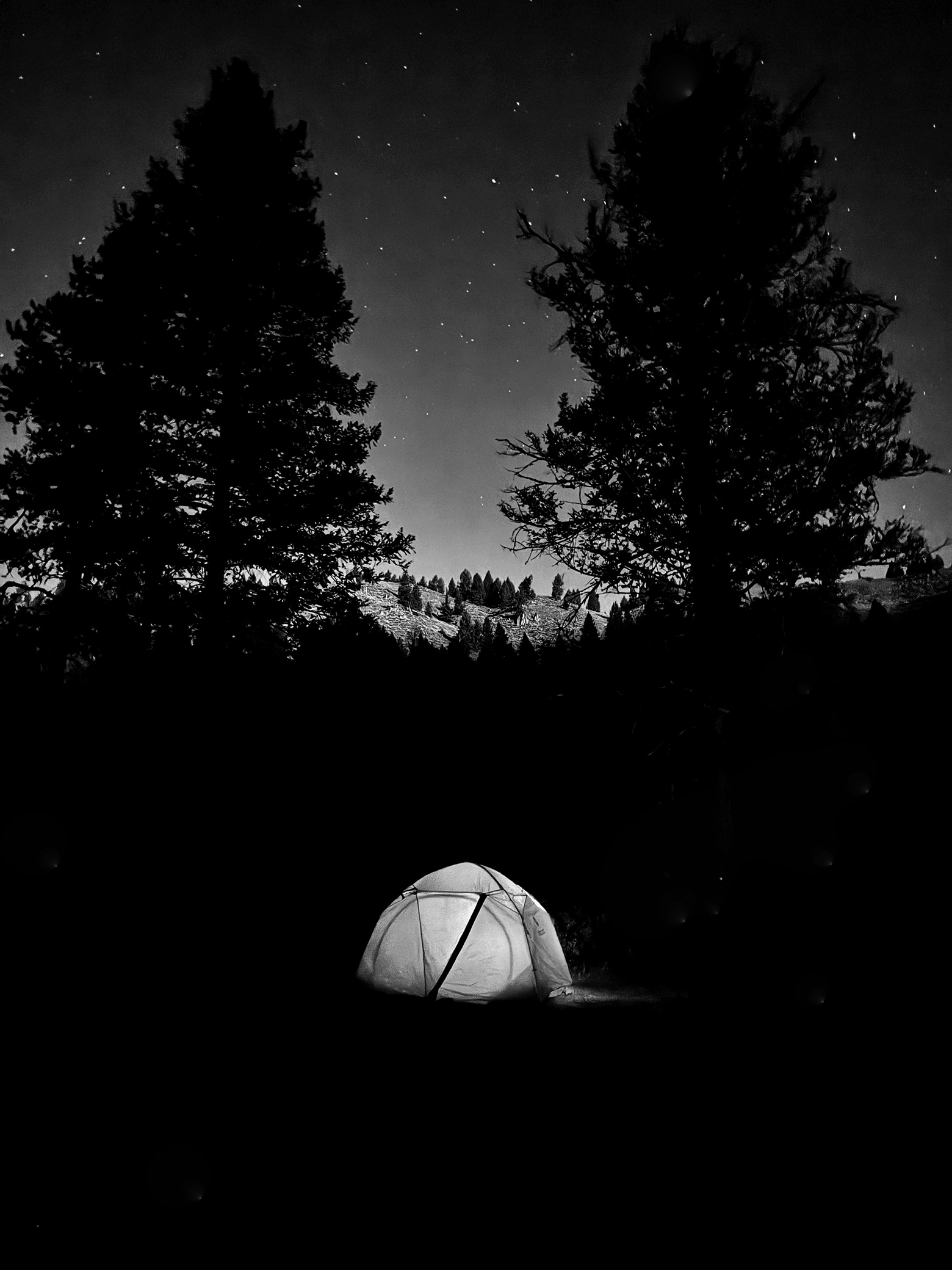

As I’ve grown older, the fearlessness I felt on that trip has waned, but I still go camping alone. I sleep better in my tent than I do at home, having usually spent the day paddling or biking. As the darkness consumes the wilderness, my body and mind can truly rest.

On one trip I was paddling the Frost River in Minnesota. It was late autumn, and only a few others were on the water. One was a man who wouldn’t leave me alone. He tried to chat me up at every portage and beaver dam crossing. When I asked him to go on ahead, he waited for me under the pretense of “helping” me with my gear and said he was worried about me being out there all by myself. I walked a fine line between being firm and trying not to anger him. In the end it was only my growling dog that kept him away.

At one point, when the river curved in such a way that he couldn’t look back and see me, I pulled over to the riverbank and unloaded my canoe. I fluffed the grass to cover my tracks, hid everything in the brush, and waited there for hours, in case he paddled back to look for me. As dusk settled in, I set up my tent and crawled in with my dog. I didn’t sleep well, but I never saw the man again.

After returning home, I relayed this all to my brother, who was furious and encouraged me to buy a pistol and get a concealed carry permit.

I took his advice, but I wear my revolver openly at my hip. Now, when I backpack alone, the men I cross paths with never stop to chat.

M.O.

Minneapolis, Minnesota

I begin setting up around 9:30 every other night: First I face two kitchen chairs away from each other in the middle of the living room, backs a few feet apart. Then I drape the soft blue blanket, which smells like me from years of cuddling on the couch, over the chairs. Finally I add a couple of pillows to block the openings and insert a flashlight.

Stepping back, I remember the blanket forts we made on rainy afternoons during childhood: special, secluded spaces whose flimsy walls provided a feeling of safety. This is the purpose of the ritual now, but it’s not for kids. It’s for our cat, Olive.

While I’ve been setting up, my wife has been preparing the treatment for Olive’s kidney disease, which involves administering subcutaneous fluids and an antiemetic. But the key ingredient is not the medicine; it’s the tent. Through much trial and error, and a few scratched arms, we’ve finally found a way to make Olive feel safe and loved during the momentary discomfort of her medical routine.

Tyler Baird

Lone Tree, Iowa

Through the opening of the tent I could see my boyfriend and our church youth-group friends sitting up in their sleeping bags by the dim light of the moon, talking and laughing. I sighed and climbed into my bag.

Our counselors said menstruation attracted bears, so women and girls having their periods were sequestered in a five-person tent for everyone’s safety. I didn’t question this decision. Some years earlier a nineteen-year-old on her period had been mauled to death by a bear in Glacier National Park. Plenty of bears wandered around our camp in Yosemite, especially if we left food out at night. Terrified, I hoped the nylon fabric would be sufficient to block the smell of blood.

After the counselors fell asleep, some of the nonmenstruating girls snuck over to the boys’ side, and vice versa, to make out for a few joyful hours. During the first week of the trip my boyfriend and I had spent every night snuggled in our bags, kissing only a few yards from the counselors, while the cool Yosemite breeze blew around us. I’d begged God for a late period, just this once. But no such luck. The blood had come in the second week.

For four nights my fear of bears overrode my desire to sneak out. Then, on the fifth night, Kotex-free, I eagerly joined my boyfriend, but the magic was gone. By the end of the summer our relationship was no more. I attributed the breakup in part to our four-night separation.

Recently I read that the idea of menstrual blood attracting bears has been debunked (except for polar bears). I wonder if the counselors knew this, or if sequestering us was an attempt to preserve our chastity, not our lives.

V.R.

Sacramento, California

I was confused by the sign: “No Tents.” Prisons have more rules than can reasonably be followed or enforced, so a critical survival skill is figuring out which ones matter. As a new inmate I was at a disadvantage, having no idea what a “tent” was.

I soon learned it referred to clothing or linens hung from a top bunk to block the view of a bottom bunk—and potentially hide drug use, sexual activity, and other prohibited acts, though in practice it was mostly used to facilitate sleep. “Lights out!” in prison should actually be “Some lights out!” because it’s never truly dark. It’s like being in a hospital: while you sleep, someone is paid to watch you, and they need light to do that.

The rule didn’t matter much to me because I was assigned a top bunk. When I wanted to sleep, I just pulled a blanket over my head. My cellmate, on the other hand, went through a nightly ritual of hanging a towel and a uniform. It seemed like a lot of work to me, but I didn’t question it.

After three years I moved to a bottom bunk and continued covering my head. But one night the light was particularly annoying, and sleep particularly elusive, so I hung up a uniform to block the light. I’ve been doing it ever since.

The light at night is just one more thing about prison over which I have no control. I don’t get to choose what I eat, what I wear, where I go, or when I go there. The message is: I’m no longer fully human. So tonight, like every night, I’ll build my tent and quietly assert that, in spite of the harm I have caused, I am still a person.

Robert Costello

Lisbon, Ohio

My papaw took me to a tent revival when I was six or seven. I’d been to church many times, but never to church outside. We waded through an overgrown field to a large army tent. Inside were crooked rows of mismatched chairs. The motley congregation who occupied them greeted one another with laughter and hard pats on the back. At the front was a crude pulpit.

The loud guitars that signaled the start of the service were nothing like the pallid piano music they played at the Holiness church my family attended. The wild, repetitive music had a hypnotic effect. Women shifted back and forth on their bare feet, raising their arms and looking toward heaven. Some produced tambourines and beat them against their thighs. Men shouted, “Praise the Lord! Glory to God!” as they walked up and down the aisle. Others sat expressionless with crossed arms; I thought they must have been from the Holiness church.

After a few songs the preacher took to the podium and began his sermon, which quickly erupted into a steady shout that he maintained, with great gasps, for what seemed like hours. When he finally settled down and asked the musicians to play again, the music was soft this time. Hushed prayers filled the tent.

“Won’t you come? Won’t you come?” repeated the preacher, now walking the aisle. One of the Holiness people rose, his face filled with anguish and covered in tears. The preacher took his arm, and when he fell to the ground at the altar, the shouting started up again. Papaw took off running, circling the tent in a sprint.

My heart was filled with a sensation that transcended emotion, as if something old had woken up inside me. I wanted to kneel beside the others, but I wasn’t sure why. I anchored myself to the folding chair and stared at the lights hung beneath the tent’s ceiling, pushing down the impulse until I could breathe again.

A few years later I had that same feeling and made my way to a proper altar, in a proper church. When I turned fifteen, I asked for a guitar for Christmas. I’ve been singing and playing at churches and tent revivals ever since.

J.K. Perry

Ashford, West Virginia

I wanted to climb a mountain, so when I met a handsome climber who said he could take me to a thirteen-thousand-foot peak, I thought myself lucky. We began dating while he plan-ned the trip. As a novice outdoorswoman I trusted him to make all the arrangements.

After eight hours of climbing we reached the peak. He suggested we could descend quickly by glissading—a kind of controlled slide—down the snowfields. Another climber cautioned me about the risk, so I hiked down instead.

Later my mountaineer encouraged me to surmount a vertical rock wall. After I’d succeeded, with great difficulty, he mentioned I should probably have been roped with a harness and helmet—it was considered a Class 5, meaning there was a high risk of falling.

On another climb my boyfriend hammered stakes through our tent’s grommets into deep snow. Exhausted, I crawled inside and slept soundly, despite the howling wind. In the morning he said he hadn’t slept a wink. He’d anchored the tent on a narrow ledge, and the winds roaring around us could easily have picked it up and sent us tumbling three thousand feet to our deaths.

Thankfully I survived our adventures. The relationship did not.

Cheri Emahiser

Tucson, Arizona

On a quest to find the perfect prom dress, my mom and I visited shops whose walls were lined with loud and billowy gowns that I had no doubt would prove unflattering to my round shape.

I timidly stepped into the fitting room with some A-lines that promised to narrow at my bust and widen like a tent below. It would’ve been easier to shop at REI. I took off my clothes and looked sadly at my reflection. Then I sucked in my stomach and pulled the first dress over my head. I quickly became lost in waves of pastel. Tangled in the fabric, I sat on the floor and cried.

Later we went to an appointment at one of the premier wedding vendors in Brooklyn, where I immediately saw the dress of my dreams: navy-blue floor-length satin, with a line of simple rhinestones around the waist and a chiffon cape to cover the shoulders. When the saleswoman approached, I shyly pointed it out.

She looked me over and said, “Most of our floor-model dresses are capped at a size 12—but, honey, we can put panels in it.” I wondered how many panels it would take to make a size 24. Would more rhinestones be needed?

In the end it cost a sum my family didn’t have, a sum I didn’t want them putting on a credit card. We left.

At home I looked at my swollen face in my heart-shaped bedroom mirror. (No full-length mirror allowed.) Then I got some books, a soda, and a bologna sandwich, and I crawled under my comforter, where I was safe.

Tina Corrado

Oaxaca, Mexico

I was still recovering from a debilitating bout of anxiety when I took my annual solo backpacking trip: a three-nighter in Yosemite, California, perfectly timed to catch the peak of the Perseid meteor shower. I got a late start at the trailhead, as usual, then was delayed by a stunning rainbow over Half Dome that required my full attention. Finally I had to traverse a large burn area, where setting up camp wasn’t an option.

By the time I passed the creek, it had been dark for an hour. In the dim light from my headlamp I mistook a substantial side trail for the main trail and took it. When it petered out, I forged ahead into a clearing, where my light caught the reflector from another tent. Though I’d planned a solo trip, under the circumstances I was relieved to have neighbors.

I set up camp and headed back to the creek to get water and bathe. It was difficult to spot trail markers in the dark, but I could hear the rushing water, so I found my way. As I headed back, I noted those same markers—or so I thought. When I crossed a trail I hadn’t seen before, I retraced my steps but ended up in a different place. I swallowed my fear, made a best guess, and climbed to a clearing to look around. No sign of my tent. I turned back, tried again, and ended up at a different part of the creek. Now I was starting to panic.

How could I have been so stupid? I knew better! People died this way.

Then a Zen-like calm came over me. Wasting energy on anger, tears, or panic would have been a mistake. I headed back to the trail again and made another loop. And another. I used my sports bra and underwear for markers. I thought of my five-year-old twin boys at home. Then my headlamp started to fade. Luckily I was wearing a watch, so I knew how long it would be before dawn. I looked up and saw incredible shooting stars with blazing tails.

I don’t how many miles I bushwhacked—sweaty, thirsty, and ex-hausted—but it wasn’t until dawn broke that I walked up a bluff, and there it was: my tent. I immediately guzzled two liters of water and made every packet of oatmeal I’d brought with me. Passing out in my sleeping bag had never felt so good.

A couple of days later I saw the couple from the other tent and apologized for pitching mine so close. They were from Europe, and I could only imagine what they thought of this wild American. Turned out they’d been wondering how I’d found the perfect place to pitch my tent in the dark.

Tammie Visintainer

Santa Cruz, California

As a teen I was desperate to leave my domineering, unpredictable father’s household. My mother counseled me to graduate high school a year early and get a scholarship. In a dormitory I’d have heat, hot showers, and three meals a day—all things I didn’t have at home. This sounded like heaven, and I made it happen. In the first two months of college I gained twenty pounds.

When my father showed up for parents’ weekend, he made a big show of taking off his sweaty shirt in the crowded parking lot and putting on a clean one. At the reception he loaded his plate with fancy hors d’oeuvres, then approached the college president to compliment the campus. The president bragged that it was five hundred acres. My father said, “And you have five hundred students, don’t you?” The president said yes. “What would you do,” my father asked, “if every student took their acre?” The president nearly choked on his pipe smoke. I was mortified.

Determined never to live at home again, I spent my first summer house-sitting while doing an internship and farmwork for money. When the house-sitting job ended, I squatted in an empty house.

As my second summer approached, I recalled my father’s conversation with the president and contemplated how I might take my acre. I bought a tent and asked a friend to chop off my waist-length hair. Then I scouted for a campsite in the woods behind the art building, which was always unlocked so I could use its bathroom. Having been a Girl Scout and having read My Side of the Mountain in fifth grade, I believed I could live off the land until I got my first paycheck from my summer job. I bushwhacked fifteen minutes into the trees and came out in a small, sunny clearing—my acre.

My first morning in the woods was a rainy one, and I wished for some shelter where I could sit and have a cup of tea. After the rain stopped, I set out to explore. Watching fish swim upstream at a waterfall, I tried grabbing one, but they were faster and slipperier than expected. I developed a mental map of where edible foods grew: wood sorrel, with its slightly lemony taste; violets; wild strawberries the size of my pinkie nail. I didn’t starve, but I also never felt full.

I found a dump where the maintenance workers and groundskeepers left furniture and other items abandoned by students as they left the dorms. I carried a tarp and chair back to my clearing, then returned for some bricks and boards to make shelves. I set out my gas stove, pot, and dishes to make my “kitchen.”

The next morning I woke at sunrise, washed my hair in the art-building bathroom, and filled my jugs. I had tea and foraged for breakfast before going to work, where I tried my best not to look like a person who lived in a tent.

I made it to payday, then set off on the long walk to town to buy peanut butter, jelly, bread, oranges, oatmeal, rice, and lentils. I knew then I would make it through the summer.

Mary Cowhey

Florence, Massachusetts

My partner and I first met at a scenic overlook while backpacking the Appalachian Trail. Shortly after that, we spent a rainy day inside a tent, from whose walls we regularly wiped away condensation. We laughed, shared stories, and tried not to eat all of our food, as we were days away from our next resupply.

The following year we hiked the Pacific Crest Trail. Every night not spent sleeping under the open sky, we were back in the same tent. We got used to the odors that result from cramped conditions and going without laundry and showers: a mix of gym bag and Desitin. Luckily we both found humor in farting—a fortuitous discovery, since backpacking food made us gassy—and that the extra body heat on freezing nights was worth the lack of personal space.

So much life was lived in that tent. We nearly smothered each other to stave off hypothermia after a snowstorm in Northern California. We took refuge from mosquito swarms in Oregon. Many times we discussed how far we should go the next day, or where we might live after trail, or if the rustling in the bushes was a bear or a deer. (It was always a deer.) On rainy nights we ate with our socks and underwear strung above us like Tibetan prayer flags. We checked each other’s bodies for ticks and applied ointment to chafed skin—and antifungal cream when I contracted ringworm. We got snippy when we were both tired and hungry. We had our first fight, made up, and shared our snacks as a peace offering.

We saw each other at our grossest and watched each other grow and come alive, attaining a level of comfort that some partners never achieve. I feel sorry for couples who don’t pass gas in front of each other. They’re missing out.

Zach Ranger

Raleigh, North Carolina

I don’t like camping. Sure, I enjoy roasting marshmallows and playing cornhole, but once it’s time to sleep in a tent, I want no part of it.

Why? Because as a teenager I lived with my parents in a tent. Trust me, it wasn’t the sort of camping experience anyone wants. One of the worst parts was having to shower with strangers, with no privacy, but even more terrible was that I also had lice, so my head was always itchy.

This wasn’t some hippie experience. We’d been kicked out of our house for not paying rent. Keeping all of this a secret from my friends was tough. Luckily I had decent clothes, so I didn’t look homeless. But the tent was muggy, hot, and cramped, and being in the middle of the woods made me anxious. I thought any noise was a bear or a serial killer out to get me.

Once school came back around, I chopped off most of my hair, and we upgraded to a small camper. I suppose I should consider myself lucky. But I’ll never enjoy sleeping within polyester walls.

Trinity Muterspaugh

Charlottesville, Virginia

I’m imagining I’m an unborn child, and the tent I’m curled up in—just large enough to hold my adult body—is my mother’s womb. Outside the tent someone reads a poem about the beauty of being born. When he finishes, I slowly push myself through the symbolic vagina. The six other workshop participants, fellow seekers of healing and truth who’ve become like family to me over the last two years, say things like “Look at this beautiful baby!” and “She’s so precious.”

I lie face up, eyes closed, and listen. They kneel by my side, and I sense them looking at me with awe. They tell me how excited they are to get to know me, how they will protect and love me.

This goes on for many minutes. Though I know what’s happening is serious and beautiful, I find myself laughing: at how ridiculous this playacting is, yes, but also at how safe and loved I feel.

Teresa Yatsko

Ithaca, New York

My four sisters and I are stuffed in the back of the family station wagon, on our way to the Gulf of Mexico, the luggage rack loaded with camping gear. I’m thirteen and already wearing my checkered two-piece swimsuit. My older sisters are flatter-chested than I am, and I’m proud of my curves.

We set up camp on the beach, using stakes as long as my arm to anchor a musty army tent for my sisters and me and a smaller one for our parents. Dad ties a canvas shade off the back of the station wagon. My sisters and I fight over who gets to eat the sugary cereals, then dash into the lukewarm waves.

By the third day I’m permitted to walk by myself to a gift shop a mile down the beach. The wind billows my hair. Fit from dance lessons and confident in my figure, I smile at a tall, muscular man with a buzz cut, who turns and asks if he may walk with me. Wow. Clearly I don’t look thirteen.

I can smell his sweat on the salt air. He peppers me with questions: Do you have a boyfriend? Where is he? Who are you here with? His eyes behind sunglasses seem nervous, glancing up and down my body. Something’s off.

A ways from the shop, I lie and say my sisters are meeting me. I’d better go. He protests. I make my voice firm and say, “It was nice talking to you. Bye now.” But I smile, having been taught to always be polite. He shrugs and turns to walk away. I continue toward the shop, wishing one of my sisters really were with me.

A couple of minutes later the man catches up with me, panting as though he’s been running. At the same time Dad pulls up alongside us in the station wagon, the canvas shade flapping, still tied to the luggage rack. My father opens the passenger door. I smile again at the man and say, “Here’s my ride. Bye now.”

One of my sisters is in the back. As we return to our campsite, she asks if I’m all right. I’m quaking but say yes. I laugh nervously when she tells me how, through binoculars, they saw the man talking to me then walking away, face furious, muttering to himself. When he started to run back to me, Mom told Dad to go, fast, and he drove off, scattering boxes of food and jerking the shade-tent stakes from the sand. I act nonchalant about it, but the joy I take in my own body has been compromised.

I wish I could say that was the last time I was ever polite to a creep.

Virginia Ewing Hudson

Medanales, New Mexico

My husband and I have owned the same tent for thirty years, ever since I accidentally washed the waterproofing from his old one. Like our bodies, the tent is getting old and brittle. I sometimes catch my toe on a yellowed curl of peeling seam tape. The zipper, twice repaired, sticks unless you hold the flap just so. White duct tape covers rips, like tissue dotting nicks on a shaven cheek.

Our last camping trip was a disappointment. We used to travel the US and Canada for two weeks every year to hike, paddle, swim, and forage for berries, seaweed, and mushrooms to liven up our camp meals. Last year we obsessively checked the weather for the next tornado or hailstorm and ditched camping some nights in favor of hotels. We trudged up mountains with tired hearts and creaky knees, breathing microparticles under ash-tainted skies. To refresh ourselves we swam in warm water of questionable purity. After a week we decided to cut the trip short.

I hung up our wet suits with my mother’s wooden clothespins, more than sixty years old. They, at least, are still intact. The rest is a toss-up. Our tent, our bodies, the Earth as we know it: Who, or what, will be the first to give out?

Ellen Vliet Cohen

Arlington, Massachusetts

My dad took me backpacking in Olympic National Park the summer I turned fourteen. We followed a trail I’d been on the previous summer with the Girl Scouts. I’d felt naive when the other girls had shared stories about sexual awakenings and, in one case, rape. At the time I’d never even had a crush, let alone kissed anyone.

Much had changed since then. A friend had told me she liked me, kicking off a romance that had ended abruptly when she’d decided I was “moving too slow.” Still, something had shifted. I knew I wasn’t straight.

I had already come out to my mother, who’d suggested I wait to tell my father. He had never been particularly touchy-feely and was not my emotional go-to, but I felt he deserved an opportunity to get to know me better. So on the way to the trailhead I conspicuously placed my copy of an alt-weekly with a “Gay Pride” headline between us on the truck’s bench seat. He didn’t comment. I wasn’t sure whether he’d even noticed.

When my dad and I were lying side by side in the tent, I gathered my courage and said, “Dad, I think I’m gay.”

After a pause he said, “No, you’re not.”

I lay there in silence until he went to sleep, leaving me to sort through my emotions.

In the nearly thirty years since, my attempts to come out to my father have all been filtered through my mother or my sister. His Parkinson’s disease limits his ability to hike, and he no longer enjoys camping. I wonder if I’ll ever find the courage to ask him what he was thinking on that trip, and if he was as scared as I was.

J.S.

Salem, Oregon

I was sleeping in a tent at a retreat center on the San Juan Islands of Washington State when I noticed my left hand reaching for the right side of my chest, my fingers grazing a lump. I realized my hand had been going there for several nights, like an animal sniffing something foreign in its environment.

I had just finished a grueling master’s program in counseling, and my energy had been dragging for the past year while I worked full-time and saw patients at my internship at Seattle Mental Health. I figured my schedule was the source of my fatigue.

The husband and wife leading the retreat had come to my school to teach a session on mindfulness. Something in their demeanor had led me to sign up for this retreat. The silent days were a balm. In the evenings we gathered in a gazebo to listen to talks on loving-kindness. Bats fluttered out of the cupola into a star-filled sky. But my right breast continued to concern me.

Back in the city the doctor said the lump I’d felt was probably breast cancer; they’d know for sure after a biopsy. It turned out to be Stage III, and it had spread to my lymph nodes. I received the full gamut of treatments, and also prayers from members of the Dalai Lama’s crew, associates of the couple who led the retreat. I’ve been told it’s somewhat miraculous that I survived.

That was twenty years ago. The name of the retreat center was Indralaya, after Indra’s net, the web that holds each of us in connection with everyone else. I still feel gratitude for the web that held me: the sweet couple, the prayers, the dedicated oncologists, and the ex-boyfriend who loaned me the tent so I could attend the retreat. The ability to slow down, pause, and enter that quiet saved my life.

Heidi Stahl

Teaticket, Massachusetts

Between long work sessions in a dark computer lab, John and I spoke about books, films, and where to find cheap eats. He was a graduate student living on a small stipend, but he had the best camping equipment money could buy, including a high-performance tent that weighed next to nothing. I borrowed a sleeping bag, and we set off for the Cascades and the Sierra Nevada every chance we got. Without another soul in sight, we jumped naked into frigid lakes to wash away the day’s sweat and soreness. Is it any wonder I fell in love?

After marriage and two daughters we bought a tent the size of a small cabin and took the kids camping in the foothills or at the beach. We huddled with other families around designated firepits, then fell asleep to voices, music, and drunken laughter well into the night. As our daughters became adolescents, they preferred the company of their friends, so we spent less time together outdoors. John held on to the old tent, thinking just the two of us would use it again, but it succumbed to mold and decay, and he finally threw it away.

A series of career failures made my husband bitter, and he grew cagey and quick to blame others for his misfortune. The threat of his anger now permeated our home. We hadn’t camped in years when, at the start of the pandemic, he announced he was buying a tent. He said he felt hemmed in, confined. It seemed a natural response, but his erratic mood of late made the purchase unsettling.

Before the tent arrived, I noticed a large transfer of money from our checking account to a credit card I wasn’t familiar with. Though I had never violated my husband’s privacy, something told me to follow this trail. What I discovered led to the end of my marriage. Let’s just say the tent was meant for two—and that didn’t include me.

After everything came to light, I demanded John leave our house.

“I don’t have anywhere to go!” he moaned.

“Oh, but you do,” I said, as FedEx pulled into the driveway with his delivery.

J.L.

Santa Fe, New Mexico

When I arrived at the Idaho State Penitentiary, it was so overcrowded that the only bunk available was in the medical tent, where the scents of urine and feces mixed with the odors of necrosis. This was a place of death and decay, and I had to live in it.

I gagged as I made my way to the pod officer, who directed me to my bunk and told me to enjoy my stay. I know people don’t think inmates deserve comfort, but this was pushing it. As I located my bunk, I saw things so atrocious it made the nursing home where I’d once worked seem like the Waldorf.

That night was probably the worst in all my time in prison. I slept only a couple of hours. There were numerous emergencies: first a heart attack, then a stroke, and finally an inmate who’d sliced off his own penis, claiming it was an alien device that had been attached to him. In the two weeks I spent there, I witnessed several deaths, attempted suicides, and men with rotting flesh. I’ve heard they have since closed down the tent, but the horrible memory remains.

Joseph Colon

Eloy, Arizona

At the start of my daughter’s fifth-grade class camping trip to the Grand Canyon, we unloaded the gear from our beater minivan, including an A-frame pup tent with aluminum supports, mesh vents, and corner stakes. We made camp in no time.

Not so for the other families, many of whom arrived in motor homes or towing RVs, travel trailers, and pop-up campers. The closest thing I saw to tents were eight-foot-high canvas condominiums replete with awnings, patios, screen doors, skylights, and, for all we knew, master bathrooms with Jacuzzis.

As her friends waved from the back seats of SUVs and upscale trucks, my daughter meekly raised her hand in response. We felt like rubes at a glamping convention.

That afternoon one of my daughter’s classmates came over to where we sat with our feet propped on the ice cooler, our outdoor ottoman. Eyeing our tent, she exclaimed, “How cute!”

She scampered off and returned with other classmates.

“Laura,” they said, “it’s adorable! Can we go inside?”

Word spread throughout the South Rim. A steady trek of classmates came to see the world’s most adorable tent. For a few hours my daughter and her classmates learned that enough can be the envy of too much.

David Shirey

Lexington, Kentucky

I once rented sixty-four square feet of real estate in Oregon—along with more than a hundred other vendors at Portland Saturday Market. Two days a week, ten months out of the year, I would erect my eight-by-eight pop-up tent and join a modern tribe of people trying to support their families with their artistic talents.

Receiving money for what I’d made with my imagination was a lifeline for me, as were my personal interactions with customers from almost every state and many nations. At times the only language we shared was the happy swap between us.

Our tents were essential for shade and as rain cover. Our worst foe, though, was the wind. I once witnessed a tiny twister lift a tent filled with framed art thirty feet in the air, then smash everything to the ground. The sound of breaking glass seemed to last for minutes. Then my fellow artists, assorted shoppers, and I ran to help. They’d done the same for me on occasion, when my booth was threatened by a storm. Receiving their help felt even better than a big sales day.

Gail Krenecki

McMinnville, Oregon

One Saturday, during a humid Florida summer, my younger brother and I decided to build a shelter. We were explorers, of course, and needed to settle in the wilderness—which for us meant the fifteen-foot-wide entanglement of trees across the street.

With our five-year age difference, there wasn’t much my brother and I agreed on, but we always knew how to band together when we needed help from a parent. We sketched out “blueprints” and recruited our dad, who said he had just the thing. He went to the shed and brought out a plastic tarp that made that awful, crinkly noise if you so much as breathed near it. To my surprise, my brother was elated. The world was far more alive to him than it was to me, and I let myself feel a little bit of his wonder.

With the tarp and some zip ties we created the most bizarre-looking structure you’ve ever seen. It all came together in an afternoon, complete with decorations and stick “furniture.” Our work done, we relaxed inside with some lemonade, feeling like explorers settling in for the evening.

The tent stayed up for years. My parents would occasionally mention that we should take it down, but it never happened. Thanks to countless storms, zero upkeep, and the overgrown landscape, it began to look dreadful. But every time our dog’s ball was thrown into the woods and I saw the tent, it reminded me of the magic that life can contain, if we welcome it.

Bayley Moore

Fort Collins, Colorado