The man kneels in her garden. All around him it is growing, so green it infuses the air with light. Which calms him. Which soothes him. Which passes the time.

His knees are dirty, the soil so deep in his skin he can’t wash it out. Earth fills his fingernails, darkens his hair. He digs with his hands, parting the soil each time as if he may never do it again. As if this time could be the last.

He plants catmint, spearmint, and peppermint because he likes their smells. He plants columbine, wild iris, bleeding heart, forget-me-nots — hearty plants, plants that will grow in the shade.

He’s been gardening for a week, ever since Katrina’s mother gathered up her daughter’s belongings and flew away into the gray-blue sky.

Katrina had been talking about the garden for years, as long as he’d known her. Some women dream of white weddings, or sandy beaches, or new diamond rings; she dreamed of spinach and lettuce, garlic and tomatoes, and tall native grass in the spring. Each day, the man looks out the window above their bed and sees that there is more to be done, that her garden is green but not green enough.

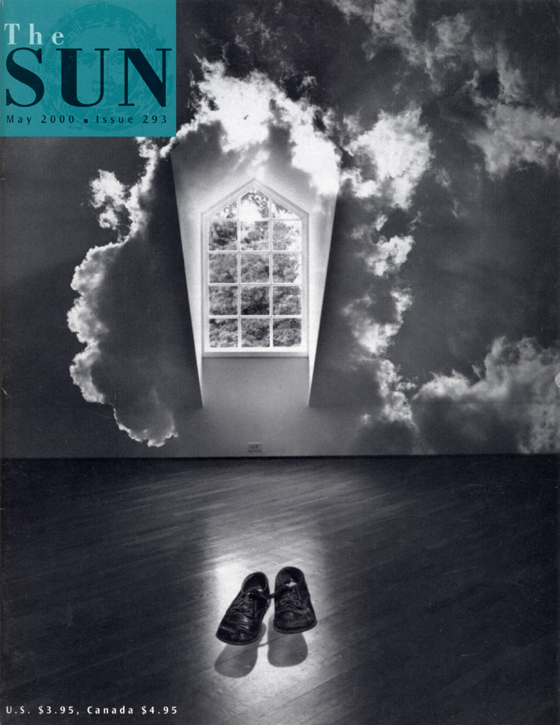

He remembers Katrina’s vision (though she wasn’t religious) of a lighted tunnel leading to God. She woke from her drug-induced hospital sleep and touched his hand and said that the tunnel was a garden, its floor a soft carpet of moss. Ancient maples lined the path, their gnarled branches arching overhead, thick with leaves.

If someone asks, he can’t say how long the work will take. A new beard grows on his face, leaf shards dangling from it like crumbs. He eats little. He wakes in the morning, sees her garden through the window, and rises, still dressed, from their bed. His clothes smell, but he doesn’t notice. He hasn’t changed his socks in days. He isn’t thinking about socks.

He pushes open the creaky screen door to the garden and begins digging and planting, weeding and pruning. Friends say he is losing weight. When they stop by with food, he regards them blankly for a moment, then continues working in her garden, protected on all sides by walls of raspberries and caragana and drooping lilac trees.

They chose the house because of the garden, though it was a wreck when they moved in. That was in September. All winter long, she came home early from the office each day and worked in her garden until dusk, preparing the beds, clearing away dead foliage, rearranging rocks, and sketching a plan for springtime. She was a planner, a scribbler, a list maker. He used to tease that her lists included such items as “brush teeth,” “sleep,” and “eat.”

There were no children, never would be. She didn’t want them, and he didn’t mind. The vasectomy irritated him, but that was more than she’d had to say about the abortion. It had been years ago, and they rarely spoke of it.

In ten years, they’d lived in five different tiny, run-down apartments — all they could afford while he was in graduate school and she shuffled papers at a law firm. Wherever they lived, she planted a garden, no matter how small: in the alley; behind the garbage shed; in a cardboard box by the kitchen window. When they moved, she’d gently dig up her favorite perennials and take them with her, all the while talking to them in a voice so tender he did not recognize it.

He did all the driving because she couldn’t keep her eyes on the road; she was always turning to look at wildflowers. Once, she’d nearly run a man over. He wondered sometimes if she wasn’t a little crazy. She admitted the possibility herself.

Now he obsesses over the dandelions that pop up in her soil whenever he turns his back for a moment. He tries to tolerate them, because she did, but his sense of order is too strong. He hates the yellow heads so soon turned to seed, their random, rampant growth. He dreams of their slippery roots slithering deep beneath the garden until the flowers and vegetables are choked and overgrown. He grinds his teeth in his sleep.

When the university hired him, he and Katrina began looking for a house. They quickly found this place, set far back from the street, the garden overgrown and wild. The columbine was still blooming, and the yard smelled of mint, licorice root, rich compost, rain. While the real estate agent showed him the inside of the house, Katrina wandered outside to pull weeds from the flower beds. Bees swarmed thickly overhead in a tree she could not name. Its small pink flowers were shaped like clogs. She called it the “pink-clog tree.”

The house was old; the stone foundation was cracking. From the bedroom window, he saw her crouched in the garden, playing in the dirt like a child. With her hand she pushed away a strand of hair that had fallen in her face; her finger left a stripe of dirt across her cheek. He knew then that they would buy the place.

The man transplants flowers from pots in the house to the garden, as she taught him. He touches the roots tenderly, the same roots she handled over the years, moving the plants from place to place. Some people move their furniture, but she had no love for furnishings. Their bed was just a plywood platform atop cinder blocks. Except for the plants, the house was nearly barren: no photographs or paintings on the walls, a few rickety stools scattered around an old card table in the dining room, and, in his study, a desk and hundreds of tattered history books stacked on the floor. The kitchen was utilitarian and smelled of garlic. They had a total of three forks, two spoons, and five dull knives. The counter tops were always gritty with dirt from Katrina’s potting, and all around hung evidence of the encroaching natural world. The man joked that Katrina wanted the house to deteriorate such that, one day, garden and house would merge.

The man hums as he works, the same song over and over again. He can’t name it, but he remembers the sound of a wooden flute and a violin. It’s as if the tune is the theme song for a movie he is in. He hums while down on his knees, his hands plowing the soil beneath the pink-clog tree. He sees a single teardrop fall and melt into the dark humus. The bees dance on the clogs as the throaty flute song wafts away on the wind.

She told him the news in the garden while she was weeding the spinach bed. “I have a lump,” she said, her voice quiet and distant, as if she were talking to the wrinkled green leaves.

The wild iris and forget-me-nots are invading the vegetable garden. He was never as big a vegetable fan as she, so he doesn’t mind. He waters the beds and tills in wildflower seeds. A patina of moss envelops the brick stairs at the back of the house, threatening to spread into the garden. He does nothing to stop it. He likes how it feels under his bare feet. He remembers how she wiggled her toes in the damp velvet growth. He remembers her tunnel to heaven.

At dawn, she’d put water on to boil, slip into her plastic sandals, and wander through the garden, never hearing the teakettle shriek. He’d rush to quiet it, pour the water over her black tea, add a dash of cream and honey, and bring it to her in the garden. She’d smile and thank him, her eyelids still puffy from sleep. She slurped as she drank — “very unladylike,” her mother would say, but it never bothered him. She slurped and walked among the rows, imagining her future flowers and carrots and peas. She touched the turning leaves of the maple tree, her skin dappled with yellow-green light.

She denied that she snored at night, though he swore he didn’t mind. Now he finds it difficult to sleep without her sound. He tries to imagine it, but it’s never quite right. He wonders what else he will forget.

Katrina’s left breast was removed three days before their first Christmas in the house. The day he brought her home from the hospital, a thin crust of snow covered the ground. She didn’t speak. She watered her plants and repotted a fern. She showed him the scar across her chest, bruised the color of eggplant, and he kissed it.

“I’m sorry,” she said, and he cried with her.

It’s springtime now in her first real garden. No more cardboard boxes and cramped, tangled roots. Next to the old gray fence, he plants her bleeding heart, which she kept alive all winter in the bathroom’s south-facing window, along with a dozen other favorite perennials. She’d take long baths in scalding water, her small right breast bobbing on the surface like a lone buoy, steam rising and gathering like dew on the leaves of her plants.

Around the bleeding heart, he places a ring of river-smoothed stones.

In February, they took her right breast. Her surgeon looked like Gandhi. He swallowed slowly when he told them, “Six months. . . . I’m sorry.”

For the first time, the man imagined their aborted child, a girl with her same lips and ringlets of dark hair, those faraway eyes. She would be seven years old, he thought. And he wanted her.

“At least I’ll see the garden,” Katrina said. “I’ll plant the bleeding heart and see the pink clogs bloom.”

Now the soil is rich and waiting, full of earthworms and beetles. Digging, the man finds bits and pieces of a child’s life: a plastic toy soldier, a broken wheel from a Tonka truck, spent firecrackers, and, next to the maple tree, a small rusted box filled with nickels and pennies. Yellow columbine and purple asters bloom alongside the house. A hummingbird sips from the feeder that she hung from the old lilac tree.

She died the last week in April, one day before his thirty-sixth birthday. The garden was just beginning to turn green, the morning chill still sharp. On his birthday, he took her spade from the garage and began digging. Rain fell, and the ground softened. He put aside the spade and dug with his hands. He dug all day, until it was time to fetch her mother at the airport. He looked at himself in the mirror: he was covered in mud. He smelled the dirt on his hands. The smell was hers.

He cried in the shower because it washed her away.

When the garden blooms, he is awestruck. Most of the flowers he cannot name. On his knees he smells them, spreads their petals to see the delicate fluted canyons of their insides. The wild irises smell like snow, the poppies like honeycomb. He sneezes and remembers her sneezing in the garden, her face squeezed tight. He likes the tiny flowers best, their transparent pink and blue petals, their leaves like lace. They grow in tight bunches on the shady north side of the house, alongside the ferns. They tremble and sway in the slightest breeze.

When he stops going to work, the chair of the history department visits, ducking under the untamed caragana branches that arch over the entryway. She is pretty, her lips like two halves of a ripe fruit.

“You’ve been granted a leave,” she says, “until the fall. Is there anything I can do?”

“I’m not coming back,” he answers, his voice hollow but certain. “I have too much work to do.”

He doesn’t see her go.

He tastes a poppy seed, a petal, a leaf. A smudge of yellow brightens his nose. He decorates a spinach salad with the poppy’s orange petals, slivers of mint and parsley. He leaves it for the deer.

Katrina’s mother was terse and unforgiving; she blamed him for not having married Katrina, though it was Katrina who had shunned marriage on principle. She picked through Katrina’s things like a raven while he dug up the season’s first dandelions.

She demanded Katrina’s ashes. The night before she left, he stole a handful from the metal urn, grains of bone and teeth between his fingers.

Each day, he lives their life again. He sees their first meeting at a college soccer game. She wore cutoffs and ran barefoot, her white skin against the rain-green hills. They fucked (she called it this, despite his protests) in an old tree fort down by a dirty trickle of a creek. Afterward, they watched the stars, and she told him about growing up on military bases in Texas and California, how dry it was, and about her father’s plastic lawn. She spoke of the garden she would have one day.

Her mother flew into the gray-blue sky with the urn.

With every planting, he adds a flake of her. Under the bleeding heart, a chip of molar; beneath the columbine, a bit of bone. The flowers take. They thrive under the rain of her as he stands, palms up in the afternoon storms. He feeds them like fish, sprinkling the ashes and watching the stems rise to accept her. The flowers bloom, again and again.