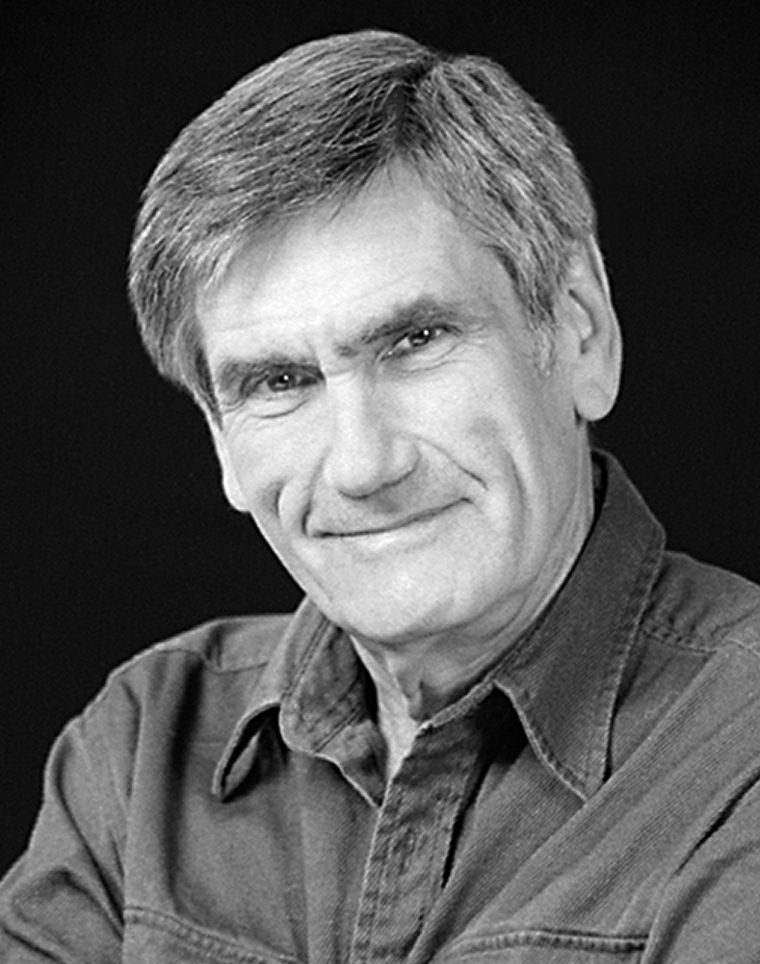

I first met Marshall Rosenberg when I was assigned by a local paper to cover one of his “Nonviolent Communication” training seminars. Disturbed by the inequalities in the world and impatient for change, I couldn’t imagine what use a communication technique could be in solving problems such as global warming or the debt of developing nations. But I was surprised by the visible effect Rosenberg’s work had on individuals and families caught in conflict.

Nonviolent Communication, or NVC, has four steps: observing what is happening in a given situation; identifying what one is feeling; identifying what one is needing; and then making a request for what one would like to see occur. It sounds simple, yet it’s more than a technique for resolving conflict. It’s a different way of understanding human motivation and behavior.

Rosenberg learned about violence at an early age. Growing up in Detroit in the thirties and forties, he was beaten up for being a Jew and witnessed some of the city’s worst race riots, which resulted in more than forty deaths in a matter of days. These experiences drove him to study psychology in an attempt to understand, as he puts it, “what happens to disconnect us from our compassionate nature, and what allows some people to stay connected to their compassionate nature under even the most trying circumstances.”

Rosenberg completed his PhD in clinical psychology at the University of Wisconsin in 1961 and afterward went to work with youths at reform schools. The experience led him to conclude that, rather than help people to be more compassionate, clinical psychology actually contributed to the conditions that cause violence, because it categorized people and thus distanced them from each other; doctors were trained to see the diagnosis, not the person. He decided that violence did not arise from pathology, as psychology taught, but from the ways in which we communicate.

Humanist psychotherapist Carl Rogers, creator of “client-centered therapy,” was an early influence on Rosenberg’s theories, and Rosenberg worked with Rogers for several years before setting out on his own to teach others how to interact in nonaggressive ways. His method became known as Nonviolent Communication.

No longer a practicing psychologist, Rosenberg admits that he has struggled at times with his own method, resorting to familiar behavior or fearing the risks involved in a nonviolent approach. Yet each time he has followed through with Nonviolent Communication, he has been surprised by the results. At times, it has literally saved his life.

On one occasion in the late 1980s, he was asked to teach his method to Palestinian refugees in Bethlehem. He met with about 170 Muslim men at a mosque in the Deheisha Camp. On the way into the camp, he saw several empty tear-gas canisters along the road, each clearly marked “Made in U.S.A.” When the men realized their would-be instructor was from the United States, they became angry. Some jumped to their feet and began shouting, “Assassin! Murderer!” One man confronted Rosenberg, screaming in his face, “Child killer!”

Although tempted to make a quick exit, Rosenberg instead focused his questions on what the man was feeling, and a dialogue ensued. By the end of the day, the man who had called Rosenberg a murderer had invited him home to Ramadan dinner.

Rosenberg is founder and director of the nonprofit Center for Nonviolent Communication (www.cnvc.org). He is the author of Nonviolent Communication: A Language of Compassion (PuddleDancer Press) and has just completed a new book, to be released by PuddleDancer in fall 2003, on the application of NVC in education: When Students Love to Learn and Teachers Love to Teach. He is currently working on a third book addressing the social implications of Nonviolent Communication.

A tall, gaunt man, Rosenberg is soft-spoken but becomes animated when describing how Nonviolent Communication has worked for him and others. He has three children and currently lives in Wasserfallenof, Switzerland. Rosenberg is in great demand as a speaker and educator and maintains a relentless schedule. The day we spoke was his first free day in months. Afterward, he would be traveling to Israel, Brazil, Slovenia, Argentina, Poland, and Africa.

MARSHALL ROSENBERG

Killian: Your method aims to teach compassion, but compassion seems more a way of being than a skill or technique. Can it really be taught?

Rosenberg: I would say it’s a natural human trait. Our survival as a species depends on our ability to recognize that our well-being and the well-being of others are, in fact, one and the same. The problem is that we are taught behaviors that disconnect us from this natural awareness. It’s not that we have to learn how to be compassionate; we have to unlearn what we’ve been taught and get back to compassion.

Killian: If violence is learned, when did it start? It seems to have always been a part of human existence.

Rosenberg: Theologian Walter Wink estimates that violence has been the social norm for about eight thousand years. That’s when a myth evolved that the world was created by a heroic, virtuous male god who defeated an evil female goddess. From that point on, we’ve had the image of the good guys killing the bad guys. And that has evolved into “retributive justice,” which says that there are those who deserve to be punished and those who deserve to be rewarded. That belief has penetrated deep into our societies. Not every culture has been exposed to it, but, unfortunately, most have.

Killian: You’ve said that deserve is the most dangerous word in the language. Why?

Rosenberg: It’s at the basis of retributive justice. For thousands of years, we’ve been operating under this system that says that people who do bad deeds are evil — indeed, that human beings are basically evil. According to this way of thinking, a few good people have evolved, and it’s up to them to be the authorities and control the others. And the way you control people, given that our nature is evil and selfish, is through a system of justice in which people who behave in a good manner get rewarded, while those who are evil are made to suffer. In order to see such a system as fair, one has to believe that both sides deserve what they get.

I used to live in Texas, and when they would execute somebody there, the good Baptist students from the local college would gather outside the prison and have a party. When the word came over the loudspeaker that the convict had been killed, there was loud cheering and so forth — the same kind of cheering that went on in some parts of Palestine when they found out about the September 11 terrorist attacks. When you have a concept of justice based on good and evil, in which people deserve to suffer for what they’ve done, it makes violence enjoyable.

Killian: But you’re not opposed to judgments.

Rosenberg: I’m all for judgments. I don’t think we could survive very long without them. We judge which foods will give us what our bodies need. We judge which actions are going to meet our needs. But I differentiate between life-serving judgments, which are about our needs, and moralistic judgments that imply rightness or wrongness.

Killian: You’ve called instead for “restorative justice.” How is that different?

Rosenberg: Restorative justice is based on the question: how do we restore peace? In other words, how do we restore a state in which people care about one another’s well-being? Research indicates that perpetrators who go through restorative justice are less likely to repeat the behaviors that led to their incarceration. And it’s far more healing for the victim to have peace restored than simply to see the other person punished.

The idea is spreading. I was in England about a year ago to present a keynote speech at the international conference on restorative justice. I expected thirty people might show up. I was delighted to see more than six hundred people at this conference.

Killian: How does restorative justice work?

Rosenberg: I have seen it work, for example, with women who have been raped and the men who raped them. The first step is for the woman to express whatever it is that she wants her attacker to understand. Now, this woman has suffered almost every day for years since the attack, so what comes out is pretty brutal: “You monster! I’d like to kill you!” and so forth.

What I do then is help the prisoner to connect with the pain that is alive in this woman as a result of his actions. Usually what he wants to do is apologize. But I tell him apology is too cheap, too easy. I want him to repeat back what he hears her saying. How has her life been affected? When he can’t repeat it, I play his role. I tell her I hear the pain behind all of the screams and shouting. I get him to see that the rage is on the surface, but beneath that lies the despair about whether her life will ever be the same again. And then I get the man to repeat what I’ve said. It may take three, or four, or five tries, but finally he hears the other person. Already at this point you can see the healing starting to take place — when the victim gets empathy.

Then I ask the man to tell me what’s going on inside of him. How does he feel? Usually, again, he wants to apologize. He wants to say, “I’m a rat. I’m dirt.” And again I get him to dig deeper. And it’s very scary for these men. They’re not used to dealing with feelings, let alone experiencing the horror of what it feels like to have caused another human being such pain.

When we’ve gotten past these first two steps, very often the victim screams, “How could you?” She’s hungry to understand what would cause another person to do such a thing. Unfortunately, most of the victims I’ve worked with have been encouraged from the very beginning by well-meaning people to forgive their attackers. These people explain that the rapist must have been suffering and probably had a bad childhood. And the victim does try to forgive, but this doesn’t help much. Forgiveness reached without first taking these other steps is just superficial. It suppresses the pain.

Once the woman has received some empathy, however, she wants to know what was going on in this man when he committed this act. I help the perpetrator go back to the moment of the act and identify what he was feeling, what needs were contributing to his actions.

The last step is to ask whether there is something more the victim would like the perpetrator to do, to bring things back to a state of peace. For example, she may want medical bills to be paid, or she may want some emotional restitution. But once there’s empathy on both sides, it’s amazing how quickly they start to care about one another’s well-being.

Killian: What kinds of “needs” would cause a person to rape another human being?

Rosenberg: It has nothing to do with sex, of course. It has to do with the tenderness that people don’t know how to get and often confuse with sex. In almost every case, the rapists themselves have been victims of some sort of sexual aggression or physical abuse, and they want someone else to understand how horrible it feels to be in this passive, weak role. They need empathy, and they’ve employed a distorted means of getting it: by inflicting similar pain on someone else. But the need is universal. All human beings have the same needs. Thankfully, most of us meet them in ways that are not destructive to other people and ourselves.

All human beings have the same needs. When our consciousness is focused on what’s alive in us, we never see an alien being in front of us. Other people may have different strategies for meeting their needs, but they are not aliens.

Killian: We’ve long believed in the West that needs must be regulated and denied, but you’re suggesting the opposite: that needs must be recognized and fulfilled.

Rosenberg: I’d say we teach people to misrepresent their needs. Rather than educating people to be conscious of their needs, we teach them to become addicted to ineffective strategies for meeting them. Consumerism makes people think that their needs will be met by owning a certain item. We teach people that revenge is a need, when in fact it’s a flawed strategy. Retributive justice itself is a poor strategy. Mixed in with all that is a belief in competition, that we can get our needs met only at other people’s expense. Not only that, but that it’s heroic and joyful to win, to defeat someone else.

So it’s very important to differentiate needs from strategies and to get people to see that any strategy that meets your needs at someone else’s expense is not meeting all your needs. Because anytime you behave in a way that’s harmful to others, you end up hurting yourself. As philosopher Elbert Hubbard once said, “We’re not punished for our sins, but by them.”

Whether I’m working with drug addicts in Bogotá, Colombia, or with alcoholics in the United States, or with sex offenders in prisons, I always start by making it clear to them that I’m not there to make them stop what they’re doing. “Others have tried,” I say. “You’ve probably tried yourself, and it hasn’t worked.” I tell them I’m there to help them get clear about what needs are being met by this behavior. And once we have gotten clear on what their needs are, I teach them to find more effective and less costly ways of meeting those needs.

Killian: Nonviolent Communication seems to focus a lot on feelings. What about the logical, analytic side of things? Does it have a place here?

Rosenberg: Nonviolent Communication focuses on what’s alive in us and what would make life more wonderful. What’s alive in us are our needs, and I’m talking about the universal needs, the ones all living creatures have. Our feelings are simply a manifestation of what is happening with our needs. If our needs are being fulfilled, we feel pleasure. If our needs are not being fulfilled, we feel pain.

Now, this does not exclude the analytic. We simply differentiate between life-serving analysis and life-alienated analysis. If I say to you, “I’m in a lot of pain over my relationship to my child. I really want him to be healthy, and I see him not eating well and smoking,” then you might ask, “Why do you think he’s doing this?” You’d be encouraging me to analyze the situation and uncover his needs.

Analysis is a problem only when it gets disconnected from serving life. For example, if I said to you, “I think George Bush is a monster,” we could have a long discussion, and we might think it was an interesting discussion, but it wouldn’t be connected to life. We wouldn’t realize this, though, because maybe neither of us has ever had a conversation that was life-connecting. We get so used to speaking at the analytic level that we can go through life with our needs unmet and not even know it. The comedian Buddy Hackett used to say that it wasn’t until he joined the army that he found out you could get up from a meal without having heartburn; he had gotten so used to his mother’s cooking, heartburn had become a way of life. And in middle-class, educated culture in the United States, I think that disconnection is a way of life. When people have needs that they don’t know how to deal with directly, they approach them indirectly through intellectual discussions. As a result, the conversation is lifeless.

If I said to you, “I think George Bush is a monster,” we could have a long discussion, and we might think it was an interesting discussion, but it wouldn’t be connected to life. . . . maybe neither of us has ever had a conversation that was life-connecting.

Killian: If we do agree that Bush is a monster, though, at least we’ll connect on the level of values.

Rosenberg: And that’s going to meet some needs — certainly more than if I disagree with you or if I ignore what you’re saying. But imagine what the conversation could be like if we learned to hear what’s alive behind the words and ideas, and to connect at that level. Central to NVC training is that all moralistic judgments, whether positive or negative, are tragic expressions of needs. Criticism, analysis, and insults are tragic expressions of unmet needs. Compliments and praise, for their part, are tragic expressions of fulfilled needs.

So why do we get caught up in this dead, violence-provoking language? Why not learn how to live at the level where life is really going on? NVC is not looking at the world through rose-colored glasses. We come closer to the truth when we connect with what’s alive in people than when we just listen to what they think.

Killian: How do you discuss world affairs in the language of feelings?

Rosenberg: Somebody reasonably proficient in NVC might say, “I am scared to death when I see what Bush is doing in an attempt to protect us. I don’t feel any safer.” And then somebody who disagrees might say, “Well, I share your desire for safety, but I’m scared of doing nothing.” Already we’re not just talking about George Bush, but about the feelings that are alive in both of us.

Killian: And coming closer to thinking about solutions?

Rosenberg: Yes, because we’ve acknowledged that we both have the same needs. It’s only at the level of strategy that we disagree. Remember, all human beings have the same needs. When our consciousness is focused on what’s alive in us, we never see an alien being in front of us. Other people may have different strategies for meeting their needs, but they are not aliens.

Killian: In the U.S. right now, there are some people who would have a lot of trouble hearing this. During a memorial for September 11, I heard a policeman say all he wanted was “payback.”

Rosenberg: One rule of our training is: empathy before education. I wouldn’t expect someone who’s been injured to hear what I’m saying until they felt that I had fully understood the depth of their pain. Once they felt empathy from me, then I would introduce my fear that our plan to exact retribution isn’t going to make us safer.

Killian: Have you always been a nonviolent revolutionary?

Rosenberg: For many years I wasn’t, and I was scaring more people than I was helping. When I was working against racism in the United States, I must confess, I confronted more than a few people with accusations like “That was a racist thing to say!” I said this with deep anger, because I was dehumanizing the other person in my mind. And I was not seeing any of the changes I wanted.

An Iowa feminist group called HERA helped me with that. They asked, “Doesn’t it bother you that your work is against violence rather than for life?” And I realized that I was trying to get people to see the mess around them by telling them how they were contributing to it. In doing so, I was just creating more resistance and more hostility. HERA helped me to get past just talking about not judging others, and to move on to what can enrich life and make it more wonderful.

Killian: You have criticized clinical psychology for its focus on pathology. Have you trained any psychotherapists or other mental-health practitioners in NVC?

Rosenberg: Lots of them, but most of the people I train are not doctors or therapists. I agree with theologian Martin Buber, who said that you cannot do psychotherapy as a psychotherapist. People heal from their pain when they have an authentic connection with another human being, and I don’t think you can have an authentic connection when one person thinks of him- or herself as the therapist, diagnosing the other. And if patients come in thinking of themselves as sick people who are there to get treatment, then it starts with the assumption that there’s something wrong with them, which gets in the way of the healing. So, yes, I teach this to psychotherapists, but I teach it mostly to regular human beings, because we can all engage in an authentic connection with others, and it’s out of this authentic connection that healing takes place.

Killian: It seems all religious traditions have some basis in empathy and compassion — the bleeding heart of Christ and the life of Saint Francis are two examples from Christianity. Yet horrible acts of violence have been committed in the name of religion.

Rosenberg: Social psychologist Milton Rokeach did some research on religious practitioners in the seven major religions. He looked at people who very seriously followed their religion and compared them to people in the same population who had no religious orientation at all. He wanted to find out which group was more compassionate. The results were the same in all the major religions: the nonreligious were more compassionate.

Rokeach warned readers to be careful how they interpreted his research, however, because within each religious group, there were two radically different populations: a mainstream group and a mystical minority. If you looked at just the mystical group, you found that they were more compassionate than the general population.

In mainline religion, you have to sacrifice and go through many different procedures to demonstrate your holiness, but the mystical minority see compassion and empathy as part of human nature. We are this divine energy, they say. It’s not something we have to attain. We just have to realize it, be present to it. Unfortunately, such believers are in the minority and are often persecuted by fundamentalists within their own religions. Chris Rajendrum, a Jesuit priest in Sri Lanka, and Archbishop Simon in Burundi are two men who risk their lives daily in the service of bringing warring parties together. They see Christ’s message not as an injunction to tame yourself or to be above this world, but as a confirmation that we are this energy of compassion. Nafez Assailez, a Muslim I work with, says it’s painful for him to see anyone killing in the name of Islam. It’s inconceivable to him.

Killian: The idea that we’re evil and must become holy implies moralistic judgment.

Rosenberg: Oh, amazing judgment! Rokeach calls that judgmental group the salvationists. For them, the goal is to be rewarded by going to heaven. So you try to follow your religion’s teachings not because you’ve internalized an awareness of your own divinity and relate to others in a compassionate way, but because these things are “right” and if you do them, you’ll be rewarded, and if you don’t, you’ll be punished.

Killian: And those in the minority, they’ve had a taste of the divine presence and recognize it in themselves and others?

Rosenberg: Exactly. And they’re often the ones who invite me to teach Nonviolent Communication, because they see that our training is helping to bring people back to that consciousness.

Killian: You’ve written about “domination culture.” Is that the same as “salvationism”?

Rosenberg: I started using the term “domination culture” after reading Walter Wink’s works, especially his book Engaging the Powers. His concept is that we are living under structures in which the few dominate the many. Look at how families are structured here in the United States: the parents claim always to know what’s right and set the rules for everybody else’s benefit. Look at our schools. Look at our workplaces. Look at our government, our religions. At all levels, you have authorities who impose their will on other people, claiming that it’s for everybody’s well-being. They use punishment and reward as the basic strategy for getting what they want. That’s what I mean by domination culture.

Killian: It seems movements and institutions often start out as transformative but end up as systems of domination.

Rosenberg: Yes, people come along with beautiful messages about how to return to life, but the people they’re speaking to have been living with domination for so long that they interpret the message in a way that supports the domination structures.

When I was in Israel, one of the men on our team was an Orthodox rabbi. One evening, I read him a couple of passages from the Bible, which I had been perusing in his house after the Sabbath dinner. I read him a passage that said something like “Dear God, give us the power to pluck out the eyes of our enemies,” and I said, “David, really, how do you find beauty in a passage like this?” And he said, “Well, Marshall, if you hear just what’s on the face of it, of course it’s as ugly as can be. What you have to do is try to hear what is behind that message.”

So I sat down with those passages to try to hear what the speaker might have said, had he known how to put it in terms of feelings and needs. It was fascinating, because what was ugly on the surface could be quite different if you sensed the feelings and needs of the speaker. I think the author of that passage was really saying, “Dear God, please protect us from people who might hurt us, and give us a way of making sure that this doesn’t happen.”

Killian: You’ve commented that, among the different forms of violence — physical, psychological, and institutional — physical violence is the least destructive. Why?

Rosenberg: Physical violence is always a secondary result. I’ve talked to people in prison who’ve committed violent crimes, and they say: “He deserved it. The guy was an asshole.” It’s their thinking that frightens me, how they dehumanize their victims, saying that they deserved to suffer. The fact that the man went out and shot another person scares me, too, but I’m more scared by the thinking that led to it, because it’s so deeply ingrained in such a large portion of humanity.

When I worked with the Israeli police, for example, they would ask, “What do you do when someone is shooting at you already?” And I’d say, “Let’s look at the last five times somebody shot at you. In these five situations, when you arrived on the scene, was the other person already shooting?” No. Not in one of the five. In each case, there were at least three verbal exchanges before any shooting started. The police re-created the dialogue for me, and I could have predicted there would be violence after the first couple of exchanges.

I’ve worked with some pretty scary folks, even serial killers. But when I stayed with it and forgot about the psychiatric point of view that some people are too damaged ever to change, I saw improvement.

Killian: You have said, though, that physical force is sometimes necessary. Would you include capital punishment?

Rosenberg: No. When we do restorative justice, I want the perpetrators to stay in prison until we are finished. And I am for using whatever physical force is necessary to get them off the streets. But I don’t see prison as a punitive place. I see it as a place to keep dangerous individuals until we can do the necessary restoration work. I’ve worked with some pretty scary folks, even serial killers. But when I stayed with it and forgot about the psychiatric point of view that some people are too damaged ever to change, I saw improvement.

Once, when I was working with prisoners in Sweden, the administrator told me about a man who’d killed five people, maybe more. “You’ll know him right away,” he said. “He’s a monster.” When I walked into the room, there he was — a big man, tattoos all over his arms. The first day, he just stared at me, didn’t say a word. The second day, he just stared at me. I was growing annoyed at this administrator: Why the hell did he put this psychopath in my group? Already, I’d started falling back on clinical diagnosis.

Then, on the third morning, one of my colleagues said, “Marshall, I notice you haven’t talked to him.” And I realized that I hadn’t approached that frightening inmate, because just the thought of opening up to him scared me to death. So I went in and said to the killer, “I’ve heard some of the things that you did to get into this prison, and when you just sit there and stare at me each day and don’t say anything, I feel scared. I would like to know what’s going on for you.”

And he said, “What do you want to hear?” And he started to talk.

If I just sit back and diagnose people, thinking that they can’t be reached, I won’t reach them. But when I put in the time and energy and take a risk, I always get somewhere.

Depending on the damage that’s been done to somebody, it may take three, four, five years of daily investment of energy to restore peace. And most systems are not set up to do that. If we’re not in a position to give somebody what he or she needs to change, then my second choice would be for that person to be in prison. But I wouldn’t kill anyone.

Killian: For horrendous acts, don’t we need strong consequences? Just making restitution might seem a light sentence for some.

Rosenberg: Well, it depends on what we want. We know from our correctional system that if two people commit the same violent crime, and one goes to prison while the other, for whatever reason, does not, there is a much higher likelihood of continued violence on the part of the person who goes to prison. The last time I was in Twin Rivers Prison in Washington State, there was a young man who had been in three times for sexually molesting children. Clearly, attempts to change his behavior by punishing him hadn’t worked. Our present system does not work. In contrast, research done in Minnesota and Canada shows that if you go through a process of restorative justice, a perpetrator is much less likely to act violently again.

As I’ve said, prisoners just want to apologize — which they know how to do all too well. But when I pull them by the ears and make them really look at the enormity of the suffering this other person has experienced as a result of their actions, and when I require the criminals to go inside themselves and tell me what they were feeling when they did it, it’s a very frightening experience for them. Many say, “Please, beat me, kill me, but don’t make me do this.”

Killian: You speak about a protective use of force. Would you consider strikes or boycotts a protective use of force?

Rosenberg: They could be. The person who has really spent a lot of time on this is Gene Sharp. He’s written books on the subject and has a wonderful article on the Internet called “168 Applications of Nonviolent Force.” He shows how, throughout history, nonviolence has been used to prevent violence and to protect, not to punish.

I was working in San Francisco with a group of minority parents who were very concerned about the principal at their children’s school. They said he was destroying the students’ spirit. So I trained them in how to communicate with the principal. They tried to talk to him, but he said, “Get out of here. Nobody is going to tell me how to run my school.” Next I explained to them the concept of protective use of force, and one of them came up with the idea of a strike: they would keep their kids out of school and picket with signs that let everyone know what kind of man this principal was. I told them they were getting protective use of force mixed up with punitive force: it sounded like they wanted to punish this man. The only way protective use of force could work, I said, was if they communicated clearly that their intent was to protect their children and not to bad-mouth or dehumanize the principal. I suggested signs that stated their needs: “We want to communicate. We want our children in school.” And the strike was very successful, but not in the way we’d imagined. When the school board heard about some of the things this principal was doing, they fired him.

Killian: But demonstrations, strikes, and rallies are often presented as aggressive by the media.

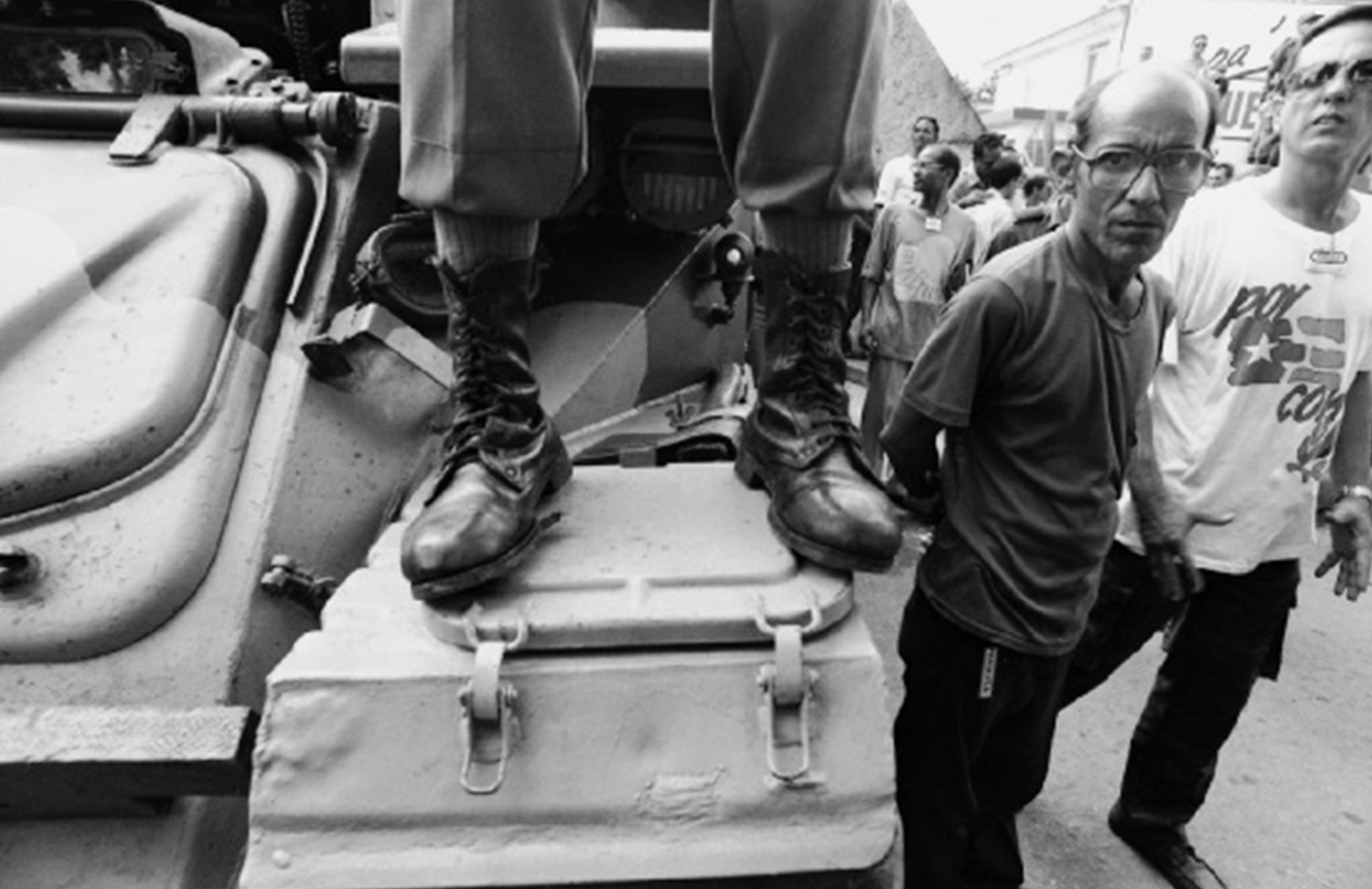

Rosenberg: Yes, we’ve seen protesters cross the line in some of the antiglobalization demonstrations. Some people, while trying to show how terrible corporations are, take some pretty violent actions under the guise of protective use of force.

There are two things that distinguish truly nonviolent actions from violent actions. First, there is no enemy in the nonviolent point of view. You don’t see an enemy. Your thinking is clearly focused on protecting your needs. And second, your intention is not to make the other side suffer.

Killian: It seems the U.S. government has trouble differentiating between the two. It tries to make war sound acceptable by appealing to our need for safety, and then it acts aggressively.

Rosenberg: Well, we do need to protect ourselves. But you’re right, there is so much else mixed up with that. When the population has been educated in retributive justice, there is nothing they want more than to see someone suffer. Most of the time, when we end up using force, it could have been prevented by using different ways of negotiating. I have no doubt this could have been the case if we’d been listening to the messages coming to us from the Arab world for so many years. This was not a new situation. This pain of theirs had been expressed over and over in many ways, and we hadn’t responded with any empathy or understanding. And when we don’t hear people’s pain, it keeps coming out in ways that make empathy even harder.

Now, when I say this, people often think I’m justifying what the terrorists did on September 11. And of course I’m not. I’m saying that the real answer is to look at how we could have prevented it to begin with.

Killian: Some in the U.S. think that bombing Iraq is a protective use of force.

Rosenberg: I would ask them, What is your objective? Is it protection? Certain kinds of negotiations, which have never been attempted, would be more protective than any use of force. Our only option is communication of a radically different sort. We’re getting to the point now where no army is able to prevent terrorists from poisoning our streams or fouling the air. We are getting to a point where our best protection is to communicate with the people we’re most afraid of. Nothing else will work.