One of the most damning things an academic can be called is an “ideologue.” A number of Sharon Hays’s colleagues have labeled her that on occasion. A professor of sociology and women’s studies at the University of Virginia at Charlottesville, Hays has written at length about the tension between capitalist competition and human relationships. After reading her work, one fellow professor angrily sputtered, “You’re just a trade unionist!”

Hays’s first book, The Cultural Contradictions of Motherhood (Yale University Press), examines how working mothers handle the demands for selflessness at home and self-interest in the workplace. Although not a mother herself, Hays says that understanding the family is crucial to understanding American culture. In her latest book, Flat Broke with Children: Women in the Age of Welfare Reform (Oxford University Press), she looks at mothers at the bottom of the income ladder — more than 90 percent of adult welfare recipients are single mothers.

To research Flat Broke, Hays spent three years interviewing welfare recipients and their caseworkers. At first many viewed the federal welfare-reform act of 1996 with optimism. The former welfare system had done little to help single mothers get off welfare, and almost everyone agreed it was in need of overhauling. Proponents of reform claimed the new system would be motivated by such worthy ideals as independence, productivity, and family unity. But, Hays says, before the act was passed into law, those ideals were compromised by politicians, policy-makers, budget-conscious states, and “scholars and pundits who sell books . . . by providing simple, provocative, one-sided portraits of complex issues.” Hays wrote her book to serve as a corrective to those simplistic accounts.

The act that was passed required mothers to work, sometimes in return for no more than the welfare benefits themselves. It brought with it a Byzantine set of rules and subsequent sanctions if the rules were not followed. And it placed a time limit on benefits; after that period was up, single mothers were on their own, whether or not they could support themselves and their children. More than two million families were dropped from the welfare rolls between 1996 and 2001. Today, despite a large number of studies tracking the results of reform, we know little about the fate of those families.

Growing up in northern California, Hays was a math whiz, and her mother encouraged her to become an engineer. In her first semester of college, however, an “Intro to Marxism” class pointed her in a different direction. She received her BA in sociology from the University of California at Santa Cruz and her PhD from UC–San Diego. Asked if she considers herself an activist, Hays replies that she took up college teaching as a form of activism. By publicly participating in rallies, she sets an example for her students, whom she encourages to get involved in community organizations.

I met with Hays at an outdoor cafe in downtown Charlottesville. We were surrounded by the trappings of the educated elite: funky coffee shops, pricey restaurants, and a store selling rare and used books. The poor in Charlottesville, Hays said, refer to the University of Virginia as “the plantation.”

As we discussed the problems that welfare mothers face, Hays’s anger was evident. She tried to contain her anger in her book, she said, because she knew that outright rage would cause many readers to tune her out before they could hear her message.

SHARON HAYS

MacEnulty: Could you briefly explain the welfare-reform act of 1996?

Hays: Its full title is the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act, and it can be understood as a social experiment in legislating so-called family values and the Protestant work ethic. It demands that single mothers participate in the paid labor force. From the moment a poor mother enters the welfare office, she must be looking for a job, training for a job, or in a job. If she can’t find a paying job, she is assigned to work full time for a state-appointed agency in return for her welfare check, an arrangement known as “workfare placement.”

After five years, all welfare recipients are expected to be self-sufficient. Many states have instituted even greater restrictions. For instance, in both of the states I studied, single mothers are barred from receiving welfare for more than two years in a row, with a five-year lifetime limit.

The act also brought with it an influx of dollars for child-care subsidies, transportation, and training. Welfare caseworkers and welfare mothers welcomed this funding, but it came with many complex rules and sanctions attached. Getting welfare became so complicated that a number of women I met simply gave up. They were worn down by all the demands. To make matters worse, some states set up workshops specifically designed to discourage women from applying for welfare.

Generally, a few instances of bad luck in a row will send a poor woman to the welfare office. It could be something as simple as getting a flat tire so she can’t get to work.

MacEnulty: If so many people originally welcomed the reforms, why do you think they turned out to be so problematic?

Hays: For one thing, the act ignores the economic, political, and cultural systems that are ultimately responsible for the large numbers of women and children living in poverty today. Second, welfare reform implicitly treats the problems of raising children, low wages, poor working conditions, and gender and race inequality as private concerns. It is as if it were the fault of individual women that they cannot raise themselves out of poverty. By this logic, there’s no need to fix our economic system; all we need to do is fix these “bad” women.

MacEnulty: Back in 1990, when I was a single mother, I got Medicaid and WIC (Women, Infants, and Children) coupons for a few months. It was relatively easy. Within a year I was back on my feet financially.

Hays: About a third of all welfare recipients are short-term, one-time users, like you were. That top third will do all right, regardless of welfare reform.

The problem with the old system of welfare was that it did not offer a way out of poverty to the two-thirds who needed it: no training, no help with child care or transportation, and insufficient income supplements. So it needed to be overhauled. And for some people, reform has been successful. But for a large group of single mothers and their children, welfare reform will be disastrous over the long run.

Proponents of reform like to point out that 60 percent of former welfare recipients are now working. What they don’t mention is that most of them will not be in that same job a year from now, and half of them aren’t earning even poverty-level wages. And you also have to consider the 40 percent of former welfare recipients who now have no job, no welfare, no source of income at all.

MacEnulty: You mentioned sanctions against welfare clients. How does that work?

Hays: The sanctions are punishments for breaking the rules. One rule, for example, is that if you quit your job, you must show “good cause.” Problems with child care, illness in the family, or just the fact that you hate your job are not considered good cause. And if you get fired, you have to prove it was through no fault of your own. If you can’t prove this, then you’re sanctioned, which means that all or part of your benefits are cut. Nationwide, about one-quarter of welfare clients are under sanction for failure to comply with welfare regulations.

Clients can also be sanctioned for failure to make job contacts, or to attend a scheduled meeting with a caseworker, or to go to all the job-training classes, or to arrive at their workfare placement on time. The rules are so complex and numerous that most caseworkers themselves can’t keep up with them, and the clients who break the rules often do so inadvertently or because of circumstances they can’t control. Half of the women I interviewed who had been sanctioned didn’t know why. The worst part is that while these women are under sanction, they do not receive benefits, but their “clock keeps ticking.” In other words, they are using up their lifetime eligibility for welfare but not getting a check.

MacEnulty: How do most welfare mothers wind up on welfare in the first place?

Hays: The most common pattern is a domino effect. For instance, your child gets sick, so you can’t go to work, so you lose your job, so the phone gets turned off, so prospective employers can’t call you, so you can’t pay the rent, and you wind up homeless. Generally, a few instances of bad luck in a row will send a poor woman to the welfare office. It could be something as simple as getting a flat tire so she can’t get to work. Or she relied on her relatives to provide free child care, and then the relatives left town.

The kinds of transportation nightmares these women go through are inconceivable to most of us. If you’re poor, jobs are usually located a long distance from where you live. So you spend three hours on the bus, shuttling the kids to child care and yourself to work. Then it’s another three hours back home. This is in addition to your eight-to-ten-hour workday.

I’ll never forget how one woman told me she was “holding on good” — until her boss switched her to the night shift. No child-care center would take her kids that late. She lost her job, and, as punishment for losing her job, she was sanctioned and lost the assistance she’d been getting from the welfare office. In short, women wind up at the welfare office because they’re poor and they’ve run out of alternatives.

I think that welfare reform is evidence of the triumph of market logic. We believe that the free market is the solution to all our problems, but the more it takes over, the more trouble we’re all in. What you see in the welfare system today is the exaggerated consequences of the triumph of market logic and the decline of our collective sense of obligation to one another.

MacEnulty: But even the mothers you interviewed seem to view self-sufficiency as a worthy goal.

Hays: Yes, on the surface, welfare reform is based on positive principles. Many people who think that welfare reform is a good idea are not mean-spirited. The trouble is that the more idealistic principles behind reform — independence, citizenship, a commitment to the common good — don’t match the reality of low-wage work, child care, and transportation issues, not to mention the plethora of family problems and, in some cases, mental and physical disabilities these women face. Given the economic realities of our times and the lack of support for raising children, it just isn’t possible for the majority of these mothers to achieve the ideal.

MacEnulty: Historically, what has been our attitude toward the poor?

Hays: A founding principle of our nation is the idea that, although we might have disdain for the poor, we are still obligated to keep them from starving to death. When welfare reform came along in 1996, it implicitly said, “If poor people can’t achieve self-sufficiency, then that’s their problem.” Period. It’s similar to what the federal government is saying to the states right now: “If you can’t make it on your own, then you deserve your fate.” Numerous states across the nation are facing major fiscal crises. Oregon, for example, can’t pay its public defenders and is closing schools early to save money.

MacEnulty: A lot of people wonder why the poor have so many children when they obviously can’t afford to take care of them.

Hays: There is a correlation between single parenthood and poverty. But saying there’s a correlation is not the same thing as saying that single parenting causes poverty. There are many, many hidden factors. Blaming parents is the wrong place to start.

Single parenting is a social phenomenon that cuts across class lines. In 1900, the rate of single parenting was 5 percent. In the 1960s, when all the furor and hand-wringing started, the rate was 12 percent. Today more than half of all American children will end up living with a single parent at some point in their childhood.

The rise of single parenting was actually prophesied by a Russian Marxist feminist named Alexandra Kollantai in 1909. She suggested that the “liberation” of American middle-class women to work for pay and to engage in “free love” would ultimately put working-class and poor women in the position of raising their children alone — with little financial support from fathers, the state, or capitalism.

MacEnulty: Are you saying the predicament of welfare mothers is the fault of feminism?

Hays: No, that would be ridiculous. But the fact is that feminism did have certain unintended consequences. In some ways, the freedoms that benefited middle-class women actually made things harder for working-class and poor women. Combine this with the disappearance of the breadwinning wage and the increasing gap between rich and poor, and the result is a class of women who don’t have the skills to make a living, and a class of men who cannot earn enough to support a family. Unemployed men aren’t considered appropriate marriage partners — although they remain bed partners — and self-sufficient women make men feel less obligated to marry. Women also ask why they should put themselves in the subordinate position of wife. These are, of course, gross generalizations, but they help us understand the issues.

The truth is that if you’re a low-income woman with children, then you’ve got very few options. Most welfare mothers want to be a part of the working world. They are hoping to find a good job and a good man. But millions of jobs have disappeared since 2001. And recent studies show that the rate of unemployment for poor single mothers is increasing at an even faster pace than the national unemployment rate.

MacEnulty: What is the “anti-abortion bonus” that you mention in Flat Broke?

Hays: The welfare-reform act included a prize of $100 million to be shared among the five states that showed a decrease in the rate of unwed births without a corresponding increase in the rate of abortion. Of course, the welfare-reform act didn’t include any proposals for family planning. In fact, it absolutely prohibited the promotion of family planning by any method other than abstinence. In one of the welfare offices I researched, the caseworkers were strictly forbidden even to mention birth control. This is a self-defeating policy. Almost no one thinks promoting abstinence is a solution.

Congress eventually decided to discontinue the anti-abortion bonus, because it found that a state’s welfare policies had no effect on its rates of unwed births and abortion.

MacEnulty: In a footnote to your book, you mention that there are no time limits on welfare benefits to children who live with relatives or other adults who are not themselves receiving welfare. What effect do you think this policy might have?

Hays: My guess is that desperate women will give their kids to the grandparents to raise, so that their kids can still get welfare. The law basically encourages poor women to give up their children.

It’s also interesting to note that many states have chosen to cook the books by removing such “child-only” welfare cases from the welfare statistics they report to the federal government. That way, the decrease in the welfare rolls appears greater than it really is. So welfare-reform proponents are calling it a “success” if you make a mom give up her kids.

MacEnulty: Yet right-wing politicians talk a lot about the importance of “family values.”

Hays: But they restrict the idea of “family” to a narrowly defined morality. They get away with this in part because there seem to be few voices on the Left that express concern about familial obligations. It’s important that the family not get lost. In this culture the family is, in fact, the central training ground for learning about obligation to others. And it teaches you to care about others no matter what their status. I mean, good parents don’t love the son who plays basketball any more than they love the son who is lousy at sports. The family teaches us how to be committed to others regardless of their achievements. Welfare reform is actually a sign that the nation is less willing to care for everyone equally.

MacEnulty: Some would say that welfare reform is a success if it saves taxpayers money. Isn’t welfare cheaper now than it used to be?

Hays: Well, taxpayers are paying somewhat less in direct aid to the disadvantaged, but those savings will be more than offset by expenses associated with social problems that will worsen as a result of reform. Look at it this way: Keeping a child on welfare costs about sixteen hundred dollars a year in cash and services. To keep that same child in foster care costs about six thousand dollars a year. And if that child winds up in prison, the cost is around twenty thousand dollars a year. Most governments figured out a long time ago that welfare is the cheapest way to keep people out of institutions — and also to keep them from taking to the streets to protest their poverty.

MacEnulty: Is there any truth to the “welfare queen” stereotype?

Hays: Ronald Reagan popularized the myth of the welfare queen. He told a story — which proved to be false — about a woman who owned real estate, drove a Cadillac, and collected multiple welfare checks. As with all stereotypes, there’s a tiny grain of truth in this one. But absolutely nobody is getting rich off a system that pays a family of three $350 a month.

It’s estimated that about 2 percent of welfare recipients engage in some kind of serious fraud. A much larger percentage simply find that welfare is inadequate for survival, so they try to somehow supplement that income. They may style hair on the side and not report that income to the welfare office. Or they may have other side jobs, like cleaning houses, or working for their landlord. And a good number of the women I met got help from relatives and didn’t report it. Technically that’s fraud, but it’s certainly understandable. In some cases, I think this behavior represents a kind of protest against the unfairness of the system. In any case, the vast majority of people who supplement their welfare check this way still wind up with an income far below the federal poverty line.

Estimates are that at least half of welfare recipients get intermittent financial help or under-the-table paychecks to feed their kids. The system is so miserly that it forces people to be unethical. But that’s a problem with the system, not with the women. I don’t want to pretend that welfare mothers are all saints, because they’re not, but they are, in general, good, honest people.

MacEnulty: Why don’t more women on welfare try to find a husband?

Hays: There’s a strong emphasis on marriage in welfare reform, but some of these women say, “All the men I know are poor, abusive, and using drugs. I don’t need these men.” If a woman has had nothing but bad experiences with men, there’s no way you’re going to convince her that getting married will solve her problems. From the point of view of poor women, there just aren’t enough suitable men to go around.

The acceptable options for women are limited: They can abstain from any kind of sexual behavior. They can be housewives, if they find someone well-off enough to support them. Or they can be supermoms who effortlessly juggle their work and family lives. But the first two roles aren’t attractive to some women, and the third is impossible for a poor single mother to pull off without help. So these women simply reject those roles.

Welfare reform is evidence of the triumph of market logic. We believe that the free market is the solution to all our problems, but the more it takes over, the more trouble we’re all in.

MacEnulty: Just as the culture has demonized “welfare queens,” haven’t we also demonized the “deadbeat dads”?

Hays: Yes, there are certainly men who have little regard for the fate of their children, but most fathers do have some sense of obligation to them. They’re simply unable to meet that obligation. For instance, there are men who make less than nine thousand dollars a year, and they owe fifty thousand dollars in back child support. If you can’t meet your obligations, the impulse to hide is strong. When poor men do skip payments, they can wind up in jail, where they’re even less able to help.

The bottom fifth of the nation’s population makes about eleven thousand dollars a year. Does that mean they don’t deserve to have children? After all, most middle-class parents aren’t sure how they’ll afford to have a baby. But they believe that they can make it work. Poor and working-class women think that things are going to work out, too. If we follow welfare reform to the letter, we consign some poor women to a life of celibacy. What’s next? Do we cut out their reproductive organs?

MacEnulty: The money spent on welfare is a pittance in comparison to other parts of the federal budget, and having a desperate and hopeless underclass only makes the U.S. a more dangerous place to live. Why doesn’t that worry the middle class?

Hays: There’s a win-lose mentality in the U.S. Americans think it’s not possible for everybody to win. Someone must be the loser. Why not the poor? And many people feel that to help the poor, they would have to give up some of their own prosperity. But the effects of welfare reform are going to be much more damaging to our prosperity in the long run.

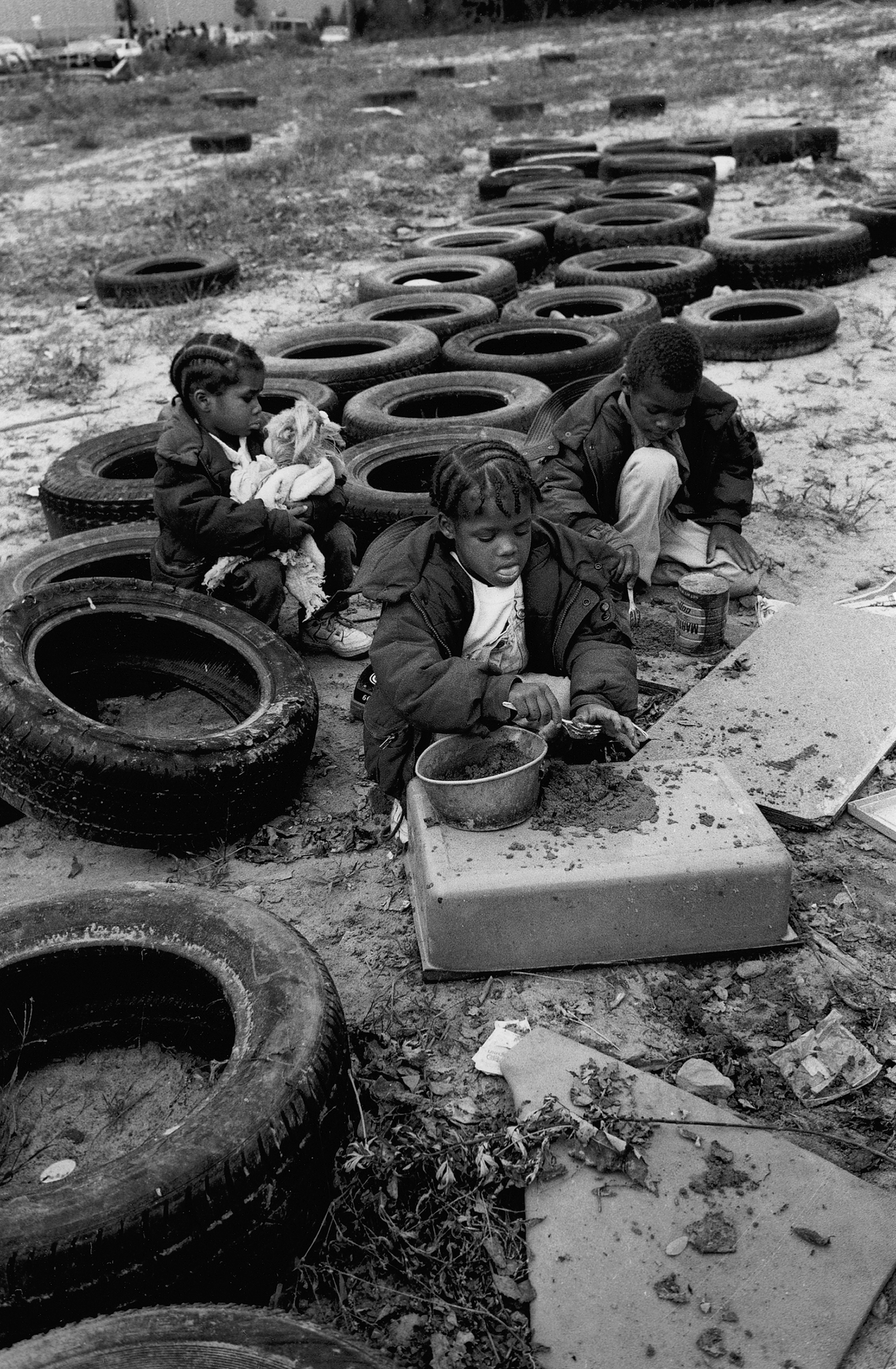

If middle-class people saw what these mothers and their children have to deal with, they would be shocked. The middle class understands what it’s like to deal with bureaucracy and the concerns of work and family, but they generally have support systems that enable them to handle it. If a welfare mother needs to take time off from her job at Burger King because her landlord has decided to sell her apartment, she’ll most likely be out of a job.

MacEnulty: Will the middle class ever see what’s going on?

Hays: The fiscal crisis in the United States is reaching overwhelming proportions. The Bush administration is forcing all the states to balance their budgets, and this means middle-class people will see the crisis in their hometowns in an immediate way. Libraries, parks, schools, even hospitals are experiencing funding cuts. Student loans are already more difficult to get. There is a general lack of maintenance of public spaces. Then, of course, you have a growing number of homeless and hungry people — many of them former welfare recipients. Food banks are already stretched to the limit. Homeless shelters are turning people away. Those people are going to show up on our streets. It is completely insane for the richest nation in the world to look like Calcutta.

MacEnulty: So welfare mothers are the proverbial canaries in the coal mines.

Hays: Exactly. Millions of Americans are experiencing problems managing budgets, jobs, and families, only to a lesser degree. What’s at stake is our hope for the future and our sense of security.

MacEnulty: Does anyone benefit from welfare reform?

Hays: Employers of low-wage workers benefit. The work requirements and the time limits force millions of desperate women into the labor market, where they have to accept the lowest wages, the most menial and demeaning work, and the worst shifts. They rarely get benefits or any kind of flexibility in their schedule. So certain segments of corporate America love this legislation.

MacEnulty: How did you feel, getting to know these women and their children, and seeing their predicament?

Hays: It was painful. In some ways it was all I could do to contain my pity and outrage. I was especially embarrassed about my feelings of pity. I would think about the size of my house and wonder, How many families could I fit in here?

The worst part was that I could see the talent and creativity of the children. I remember a smart, self-sufficient four-year-old boy whose mother had just been diagnosed with cancer. Her doctor told her she needed chemotherapy; her employer told her if she didn’t show up for work, she’d be fired; and the welfare office told her that if she didn’t work, she’d lose all her benefits. The U.S. disability system is so slow and tightfisted that the only way she’s likely to get help from it is if she is diagnosed as terminal, and even then she probably won’t get the financial help until after she dies. So what will become of her little boy then? This level of cruelty astounds me.

MacEnulty: What did she do?

Hays: When I saw her last, she was still trying to imagine a way out. I saw that kind of resilience often. I was amazed by it, and yet it also worried me. When I think about the impact of welfare reform, I am simultaneously angry and heartbroken.

MacEnulty: It’s been about eight years since the welfare-reform act went into effect. Some women must have maxed out their benefits by now. Do you have any idea what has happened to them?

Hays: I’ve managed to find a few of them, but the fact is that the women who have hit the time limit are also the most difficult to track. Many of them are without work, and once they’re off the welfare rolls, there’s almost no way to find them. They don’t have telephones and often aren’t in contact with their extended families. Maybe they’re homeless. They are likely to disappear. We’re not just talking about a mom; we’re talking about a mom with kids.

MacEnulty: Do you think any of the women will turn to criminal activities to support their children?

Hays: There’s no question that some portion of them will engage in prostitution, petty thievery, and various aspects of the drug trade. I want to emphasize that most of the women I met are incredibly reluctant to do this, not just because it’s illegal, but because they don’t want their kids to see this kind of activity. Having children makes being honest and avoiding illegal activities very important to them. But these women have nowhere else to go.

MacEnulty: This welfare-reform act was enacted during the Clinton years, when we were supposedly under a more compassionate administration. Has the Bush administration made any changes to welfare reform, for better or worse?

Hays: Welfare reform was set up to last six years, so the states could experiment with it. The reauthorization period came and went, and Congress keeps putting off dealing with it because its members can’t agree on what should be done. As much as there is continuing disagreement between Democrats and Republicans on just what to do, all the proposals debated in Congress thus far in 2004 would result in a more punitive and demanding welfare system than the one we have now. Welfare caseworkers and state-level policymakers are on the edge of their seats, wondering how much worse it’s going to get.

The Bush administration has already added funding for monetary marriage bonuses and marriage-promotion workshops. But many of the women on welfare are domestic-violence survivors. The notion of promoting marriage to them is laughable.

The proposals also demand that states place a much larger proportion of recipients into “work-related” activities, while at the same time decreasing the states’ flexibility in determining which activities count as work-related. Local welfare offices have spent the last six years frantically trying to meet the federal and state rules. All the proposals would require an increase in the percentage of welfare mothers who must work. And all of these proposals decrease the flexibility of states in trying to manage this. So they’ll be forced to create additional unpaid workfare placements.

The states are punished for their failures, and they can’t afford to lose any more federal funding. No matter how much states or local offices might want to protect some of these families, such as moms with disabled kids, or domestic-violence survivors, it will be impossible for them to do so.

This is what we see on the horizon. Welfare activists have mobilized, but it seems no one is listening. People are understandably distracted by the war in Iraq, and many have also been duped by reports of the so-called success of welfare reform.

MacEnulty: Then what can be done?

Hays: We need to broaden the positive aspects of welfare reform — the supports for child care, training, and transportation — while eliminating time limits, excessive paperwork, and sanctions. We also need to recognize that some women simply have too many responsibilities for them to work outside the home, and we should pay them for their work as caregivers. In many cases, welfare is much cheaper than making a woman go to work for $7.20 an hour while taxpayers pay for her child care.

But in order to really lift people out of poverty, we need a fundamental restructuring of the labor market to take families into account. We have to recognize that most workers are also parents. This means providing a living wage, health benefits, subsidized child care, and flexible hours.

Ronald Reagan popularized the myth of the welfare queen. . . . But absolutely nobody is getting rich off a system that pays a family of three $350 a month.

MacEnulty: You recently went to Norway for an international conference. How do we measure up compared to other countries?

Hays: We have the most miserly welfare system in the Western world. All the Scandinavian and Western European countries have income-equalizing policies and subsidized child care, so everyone can be assured at least a minimum standard of living, and those parents who want to stay home with the children can do so. People in those countries consider anything less to be completely inhumane.

The Scandinavians, in particular, found it inconceivable that this harsh treatment of the poor could take place in the richest nation in the world. They asked me, “But don’t Americans understand that these are innocent children?”

MacEnulty: Why are we so much more miserly than these other countries?

Hays: When you have the immense gap between the rich and poor that we now have in the U.S., the rich basically control politics, and they draw all the benefits to themselves. The Europeans are also much more accepting of the idea that the government can provide aid to the disadvantaged and programs and support for all citizens. Americans, on the other hand, think of government as more of an ominous Big Brother than a benevolent provider.

MacEnulty: You say in Flat Broke, “In the long run, it is quite possible that many welfare mothers . . . will organize and mobilize against the system that, to many, had seemed so right during those early years of reform.” I wonder if that’s remotely possible, given the hegemony that the market logic seems to enjoy in American culture.

Hays: At the moment, you’re right. There’s a sense of shame among many of the welfare mothers I met who were having a hard time getting by. They’d get jobs, then lose them and have to go back to the welfare office even though they didn’t want to. They might be angry, but many of them also felt like failures. How do you convince them to protest against the system? It does seem as if the market has won.

But there is hope. History is full of poor people’s movements. Even though they are poor, even though the system operates to make them voiceless, they can eventually organize against the system. If you drive this many people to absolute desperation, they will speak up. Disorganized protests — race riots, looting, and so forth — will occur, and organized protests will follow. And there’s good reason to believe we’re headed in that direction. The story of welfare reform is not over.