In the West, therapy is often seen as an opportunity to express our feelings about past trauma or current conflicts. Releasing pent-up emotions improves our mental health, or so the theory goes. Gregg Krech has a different theory. He believes that, rather than expressing our anger or hurt, we would be better off focusing on all the care and support we’ve received in our life. When we “develop a sense of appreciation for those around us and cultivate a sense of gratitude for life itself,” he writes, “we are relieved of the burden that comes with seeing ourselves as ‘victims.’ ”

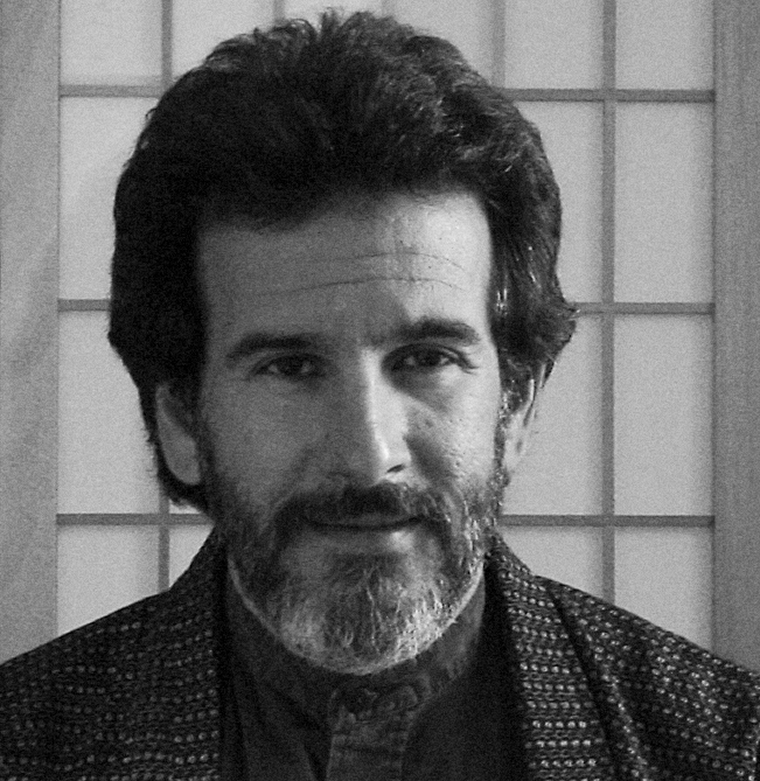

Krech (pronounced “Kreech”) and his wife, Linda Anderson Krech, are the founders and operators of the ToDo Institute, a nonprofit center in Monkton, Vermont, that offers educational programs on Japanese psychology. On a recent visit to the institute, I practiced a form of self-reflection called Naikan (pronounced “Nye-con”), which translates as “inside looking.” Naikan is structured to focus our attention on our own conduct in relationships with parents, siblings, friends, partners, co-workers, and neighbors. It also encourages us to accept life’s events rather than become mired in our feelings about them.

I sat on a cushion, looking at a bare white wall, and considered my relationship with my neighbor, who often hosted live-music sessions on her front porch — sometimes when I was trying to study or sleep. Though she accommodated my requests to limit the gatherings to certain times, the noise still bothered me. (I am a lover of silence.) As I sat there on my cushion, surrounded by shoji screens, I tried to answer three questions: What had I received from my neighbor? What had I given her? And what difficulties had I caused her? I was surprised to realize that I had received more from my neighbor than I had given. I began to see my behavior from her perspective, almost as though I were looking at myself through a window of her house. The experience was both revealing and unsettling.

Krech first learned about Naikan from the book The Quiet Therapies, by cultural anthropologist David K. Reynolds, who first introduced Naikan and Morita (another Japanese therapy) to the U.S. in the 1960s. In Japan, Naikan has been used for decades as a therapeutic technique and conflict-resolution tool in the workplace, marriage counseling, addiction clinics, and prisons.

Though Reynolds de-emphasized the spiritual roots of the “quiet therapies,” it was Naikan’s compatibility with spiritual traditions — Buddhism in particular — that attracted Krech. A native of Chicago, he had encountered Buddhism and Eastern philosophy during his undergraduate years at Northern Illinois University. He went on to study Zen in the U.S. and Japan and has been a practicing Buddhist for more than twenty-five years. He has traveled extensively in Asia and worked with orphans in refugee camps on the borders of Laos and Cambodia, where he saw firsthand the costs and tragedies of war. (Many years later, he and his wife adopted two young girls from China and Vietnam.)

Today Krech is one of the leading authorities on Naikan in the U.S. He is the author of Naikan: Gratitude, Grace, and the Japanese Art of Self-Reflection (Stone Bridge Press) and the editor of the ToDo Institute’s quarterly journal, Thirty Thousand Days: A Journal for Purposeful Living. His wife, Linda, in addition to helping run the institute, is a social worker who has used Naikan in her work with people who have severe mental illness. The ToDo Institute (website: www.todoinstitute.org) is housed in the cozy farmhouse where Gregg and Linda live with their daughters, Chani and Abbie, and a golden retriever named Barley. As Krech and I sat down to talk, he told me that he’d recently begun taking Suzuki-method violin lessons along with his daughters. Both Suzuki and Naikan, he explained, emphasize consistent, methodical practice in order to integrate a skill into one’s daily life.

GREGG KRECH

Winter: When was Naikan developed, and by whom?

Krech: Naikan was developed in Japan in the early 1940s by a man named Yoshimoto Ishin. Yoshimoto was a devout Buddhist who in his later years became a successful businessman. His background was in a somewhat secretive Buddhist practice called mishirabe, which involved going into a cave and meditating on your life for days without food, water, or sleep. It wasn’t the kind of practice that appealed to many people. Yoshimoto decided to create a method of self-reflection that would maintain some of the characteristics of mishirabe, but not be so dangerous or arduous. He wanted to make it accessible.

Yoshimoto developed Naikan over a period of three decades. The name means “inner observation,” or “seeing one’s self through the mind’s eye.” Rather than sit in a cave, people would come to a Buddhist temple and sit facing a wall or behind Japanese shoji screens. It was still intense, but compared to mishirabe, it was luxurious. In the decades that followed, many secular Naikan centers formed. The last I heard, there are around forty such centers in Japan.

As a psychological practice, Naikan has a big advantage over a lot of Western psychology, which is often at odds with the values of spiritual and religious traditions.

Winter: How so?

Krech: While I was studying Buddhism as a young man, I was also interested in psychology. I would look on the self-help and psychology shelves in bookstores and see titles like Looking Out for Number One and How to Get the Love You Want. I couldn’t reconcile this with Buddhist — and also Christian and Judaic — values such as selflessness, gratitude, service, and compassion. It’s often hard for people who are more spiritually oriented to be in therapy, because they run into these same contradictions.

I think a lot of Western psychology takes a somewhat hostile view of religion and spirituality. If you’re a psychologist, you might find that your own spiritual tradition helps you handle the more challenging moments of your life, but you’re not allowed to make reference to it in a clinical setting with a patient or client.

It’s common for someone in counseling to blame other people — parents, spouses, exes — for the way he or she is. Little time is given to developing a sense of appreciation for what other people have done for you, or to looking honestly at what you have done to cause them suffering. I would argue that gratitude and self-examination, which are the focus of Naikan, are more consistent with a spiritual approach to life than expressing anger and blaming others.

Winter: In your book you say that psychology is more of a philosophy than a science. Why do you believe that?

Krech: There’s been a great push to medicalize psychological problems and put psychology on par with medicine as a science, but I don’t think the comparison holds up. If a doctor takes your blood pressure, that’s an objective, scientific measurement. Another doctor, taking the same test at the same time, would get the same result. Compare that to a child who is evaluated for attention-deficit (hyperactivity) disorder: A psychologist observes the child’s behavior in an office setting for an hour, checks off a list of behaviors, and gives a diagnosis. If you take that child to a different psychologist, you may get a completely different diagnosis. This is because psychological diagnoses are founded on issues of politics, money, and power, as well as science. Homosexuality was on the list of psychological disorders until mental-health experts lobbied to remove it. The decision was a good one, but it wasn’t driven by science; it was driven by social and political beliefs.

When it comes to treatment, too, psychology offers far more options, based on far less science, than medicine does. If you’re depressed, one psychologist might decide you have underlying issues with your parents, another might believe your depression is mostly chemical, and a third might suggest that it’s because you don’t find enough meaning in your job. I don’t see anything wrong with this system, as long as we’re honest and admit that it more closely resembles going to a philosopher or religious teacher for advice than it does going to a doctor.

I don’t see Naikan as a science; I see it as a meaningful spiritual practice. It’s important to practice self-reflection, particularly in our busy society, where there’s so much emphasis on action.

Winter: How do Western mental-health practitioners respond to Naikan as a therapeutic tool?

Krech: It depends to a great extent on the person. It’s very hard for someone who has invested in years of training in a particular paradigm to be introduced to something that in many ways shatters that paradigm. Although a large portion of therapists are personally involved with some kind of spiritual practice that works for them, they don’t feel they can offer it to people professionally.

In Japanese psychology, on the other hand, you’re supposed to offer people what works for you. You use your own experience. If you’re a therapist and want to use Naikan with clients, the first thing you must do is practice it. That’s what gives you credibility and makes your relationship with the client genuine. And I think some Western therapists are looking for settings in which to do that. There are not many such opportunities outside of private practice, because most clinical settings do not condone offering prayer, or meditation, or yoga, or anything spiritual to clients.

I think there’s a growing movement to try to integrate therapy and spiritual values, but there are also a great number of people who are invested in the growing use of medication as a solution to all psychological problems, and they’re not at all interested in this.

Winter: Can you describe a typical retreat experience?

Krech: We do several one-week retreats a year. You wake up around 5:30 and have about twenty minutes to do your morning routine. Then you sit on a cushion in a corner, facing the wall. You don’t have to sit in any particular posture, and you’re surrounded by screens, for privacy.

You reflect on your life in a systematic way, focusing on a particular person and period of time. Traditionally you start with your mother, and you look at the period from the time you were born until you were nine years old. The reflection is based on three questions: What did I receive from my mother during that time? What did I give her? And what troubles and difficulties did I cause her? After an hour and a half to two hours of silence, somebody will come to do what we call “mensetsu,” which means “face-to-face interview.” It’s basically an opportunity for you to report what you’ve remembered. You list, in as much detail as you can, the things your mother gave you.

It’s important to be specific. For example: “On my seventh birthday, she made a big chocolate cake and drew a clown face on it, and she hired a clown to come to my party.” Or, “I played Little League baseball, and a game got rescheduled at the last minute. My uniform was all muddy, and my mom got up early to wash and dry it so I would have a clean uniform.”

After you’ve reported what you received from your mother, you then list the things that you gave her. Maybe you made her a Mother’s Day card, or you took the garbage out. Then you move on to the third question: the troubles and difficulties that you caused.

The person who’s listening is there just to listen. This is one of the real departures, I think, from Western therapy, where the therapist is expected to respond in some way. When you’re done with mensetsu, the listener thanks you and says, “Please go on to the next three-year period.” (After the first nine years, you generally work with three-year segments.) There’s no discussion or dialogue. The staff is mostly there to do your laundry, bring you meals, and provide a serene environment in which you can examine your life.

Most people struggle with what we call the “absent fourth question,” which is: What troubles and difficulties did this person cause you? People often have a strong interest in asking that question, but if they’re allowed to do so, they get off track. If somebody has done something to you, one hopes that at some point they’ll reflect on it themselves, but in my opinion, it doesn’t do you much good to dwell on it. Probably you’ve dwelt on it plenty already.

So I try to help people stay within the boundaries of the three questions. For those who are used to criticizing and complaining about other people, it’s a big change, but once they understand the framework, it often becomes helpful or even healing for them.

Winter: What about people who have experienced truly horrible childhood traumas?

Krech: Most people have challenging or emotional events in their lives that are difficult for them to reflect on. When somebody’s had a particularly traumatic experience, there’s often an assumption that the person has to get in touch with the pain of that experience and express that pain in order to heal, which often means expressing anger toward the person who caused that pain.

Winter: The catharsis model.

Krech: Yes, but over the years that I’ve been doing this, I’ve come to believe that the theory behind that model couldn’t be farther from the truth. When someone’s had a traumatic experience and continually talks about and revisits that experience, it becomes the dominant event of his or her life. Naikan says that, even though this experience took place, it’s not the dominant event of your life. It was one part of your life, and so was this, and so was this, and so was this.

When someone’s had a traumatic experience and continually talks about and revisits that experience, it becomes the dominant event of his or her life. Naikan says that . . . it’s not the dominant event of your life. It was one part of your life.

Winter: If, say, an incest survivor were to come for a retreat, would you ask that person to consider the ways in which he or she caused trouble for the perpetrator?

Krech: That’s a difficult subject. At the proper time, yes, I would ask, because it’s part of what needs to be done, but it certainly isn’t something I’d ask someone to do the first time I met them.

Let’s say a woman had an uncle who raped her when she was eight. She might begin by doing Naikan on all the other people in her life. And she’d begin to see the overwhelming flow of support that was necessary to keep her alive and, in most cases, thriving.

It’s possible, of course, that someone received very little support. But most people who do Naikan haven’t grown up in a refugee camp or a war zone; they come from some of the wealthiest societies on the face of the earth. It’s this wealth that allows them the luxury to come and do Naikan. So they did receive practical care and support as they were growing up.

At some point during the week (and I’m always very careful about when to do this) I’d ask this woman if she wanted to do Naikan on her uncle. I’ve dealt with many such cases, and most of the time the person will say yes. If our hypothetical woman is like many other people I’ve worked with, she’ll begin to see that, outside of that abuse, her uncle also took her to baseball games or drove her to piano lessons or took her to the beach. He isn’t just “the rapist.”

This has nothing to do with justifying or excusing or condoning the rape. The goal is to perceive life in its entirety.

Years ago I read an article in the Washington Post about a man who was on death row in Virginia for brutally killing two teenage girls. The journalist had interviewed people who knew the man. A former co-worker remembered that he’d helped change a flat tire. The man’s children said he used to take them to barbecues and picnics on Memorial Day. The point is that it’s easy to condone capital punishment if we think of the condemned just as “the murderer,” but it’s much harder when we realize that this person had a life apart from his horrendous crimes. He was a human being like the rest of us, who had different sides to his person: some selfish and evil, others helpful and kind.

In our hypothetical situation, it’s all too easy to look at this uncle solely as a rapist and pretend he never did anything else in his life but rape this woman when she was eight years old. What’s harder to see, without condoning in any way what he did, is that he also did other things in his life, perhaps including things to help this person.

So when the woman does Naikan on her uncle, she begins to see some of these things that he did for her, and some of the things she did for him, and then the troubles she may have caused, which might even include telling her mother what he’d done or reporting it to the police. (Of course, just because it caused trouble for him doesn’t mean she was wrong to do it.) In the end, she comes away with a more accurate picture of this uncle and her relationship to him.

To me, healing comes from the awareness that our pain and suffering take place in the context of a life that is mostly full of love and support. But suffering remains a part of our life, because what choice do we have when we’ve gone through that kind of experience? When a wound heals, it often leaves a scar. We have to accept that.

It’s humbling to look at each year of your marriage and recall all the suffering, trouble, inconvenience, and difficulty that you caused your spouse. . . . It creates an atmosphere in which people can come together to solve practical problems, because it counterbalances all the tension and resentment and anger.

Winter: Getting back to the problems faced by the average person who does Naikan: What if someone can’t remember specifics? I don’t think I can remember very many small details from when I was four or five.

Krech: We think that we won’t be able to remember much because few of us have actually tried to remember in a concentrated way. I mean, how many of us have taken an hour to face a blank wall and think of nothing but our early relationship with our mother?

What I find is that, by the end of the week, most people remember much more than they ever thought they would. I’ve done five retreats in Japan, looking at the same periods of my life, and I remember something new almost every time.

During the last retreat, I remembered my seventh-grade class doing the play The Legend of Sleepy Hollow. A boy named Marty and I were responsible for creating sound effects with a reel-to-reel tape recorder. The amazing thing was that I actually remembered the brand of tape recorder: a Wollensak. I could even remember the font used to write “Wollensak” on the side of the tape recorder. I could almost draw it for you. It’s a meaningless detail, but it illustrates the point that our memories are much more accessible than we think. The flip side of this is that people almost always have at least some period of their life of which they remember little or nothing. If you can’t remember, you just go on to the next period.

Winter: I’ve heard that a common assignment given to participants in a Japanese Naikan retreat is to calculate the number of diapers their parents changed for them when they were a baby. This seems a little silly. Isn’t it enough just to acknowledge that your parents changed a lot of diapers?

Krech: I can’t say my mother changed “a lot” of dirty diapers for the same reason my bank statement doesn’t say I wrote “a lot” of checks, and the deed to my property doesn’t say I have “a lot” of acreage. Truth is in the details. That’s all there is. Generalizations get us farther from the truth. In Naikan we are trying, as much as possible, to reflect on facts. Our estimates may not be as precise as a bank statement, but they do give us a more accurate understanding than generalizations would.

Winter: But isn’t it a parent’s responsibility to change diapers? Surely they realized it was part of the bargain when they chose to have children.

Krech: I’m happy to acknowledge that parents have a responsibility to care for children, particularly young children. I’ll even concede that people’s reasons for having children are often selfish. But why should that absolve us of our responsibility to acknowledge the care that kept us alive and healthy when we were children and unable to take care of ourselves? Naikan simply asks that we look at the facts of the situation: I received twelve swimming lessons and five years of piano lessons. I received dental care and eyeglasses when I needed them. I received more than two hundred rides to baseball games and a new bicycle on my ninth birthday. I didn’t pay anything for these goods and services. The few times I bought anything, the money came out of the allowance that my parents gave me.

Too often the facts get mixed up with feelings or speculation about the other person’s intentions or obligations. There is great power in just looking at the facts of our life without embellishment.

Winter: When Naikan is used in a therapeutic setting, is it different from the type of self-reflection you’re describing here?

Krech: A lot depends on the person’s reason for coming to us. Some people aren’t interested in learning about Naikan as a spiritual practice; they’re interested in keeping their marriage from falling apart. I know a couple who had been married for nine years and were on the verge of divorce. They had been to a number of different counselors, but nothing seemed to help. I recommended that they both come here for a day and do Naikan on each other. They were interested in trying to save the relationship, so they came. I don’t want to make it sound like a magic cure that works for everybody, because it isn’t, but I got an invitation three weeks later to a renewal of their vows. What will happen next, I don’t know.

It’s humbling to look at each year of your marriage and recall all the suffering, trouble, inconvenience, and difficulty that you caused your spouse. It’s hard to be judgmental of the other person when you see all your own faults and limitations in the relationship. It creates an atmosphere in which people can come together to solve practical problems, because it counterbalances all the tension and resentment and anger.

Winter: Are there situations in which Naikan isn’t appropriate?

Krech: A question that comes up a lot in workshops is “What about a woman who’s being beaten by her husband? What if she does Naikan on him and decides to stay with him? Do we really want that?” I think this concern is based on the idea that Naikan will turn people into passive wimps. And I don’t think that’s true. One can cultivate the qualities of empathy, appreciation, and compassion without becoming passive. In some cases self-reflection stimulates action, as we realize that our own inaction has been a source of trouble or contributed to the suffering of others.

There are some people who do Naikan and come away depressed, because they’ve just realized that they’ve done all these terrible things in life, and it doesn’t feel good. Here’s another departure from Western therapy, where the purpose is to help people feel better about themselves. If a therapy doesn’t help you feel better, we think, it’s not working. In Naikan, the purpose isn’t to help you feel better. It’s to help you see the truth of your life. Seeing the truth of your life may initially make you feel terrible, but if you’re committed to truth, then the question of how you feel is not the main issue.

I tell people when they come in for a retreat that there are times when Naikan does not make you feel good. It’s rare for that to be the outcome of the retreat, but it could happen. And it doesn’t mean that there’s anything wrong with the process or with the person.

Winter: So what happens then? What do they do with that terrible feeling?

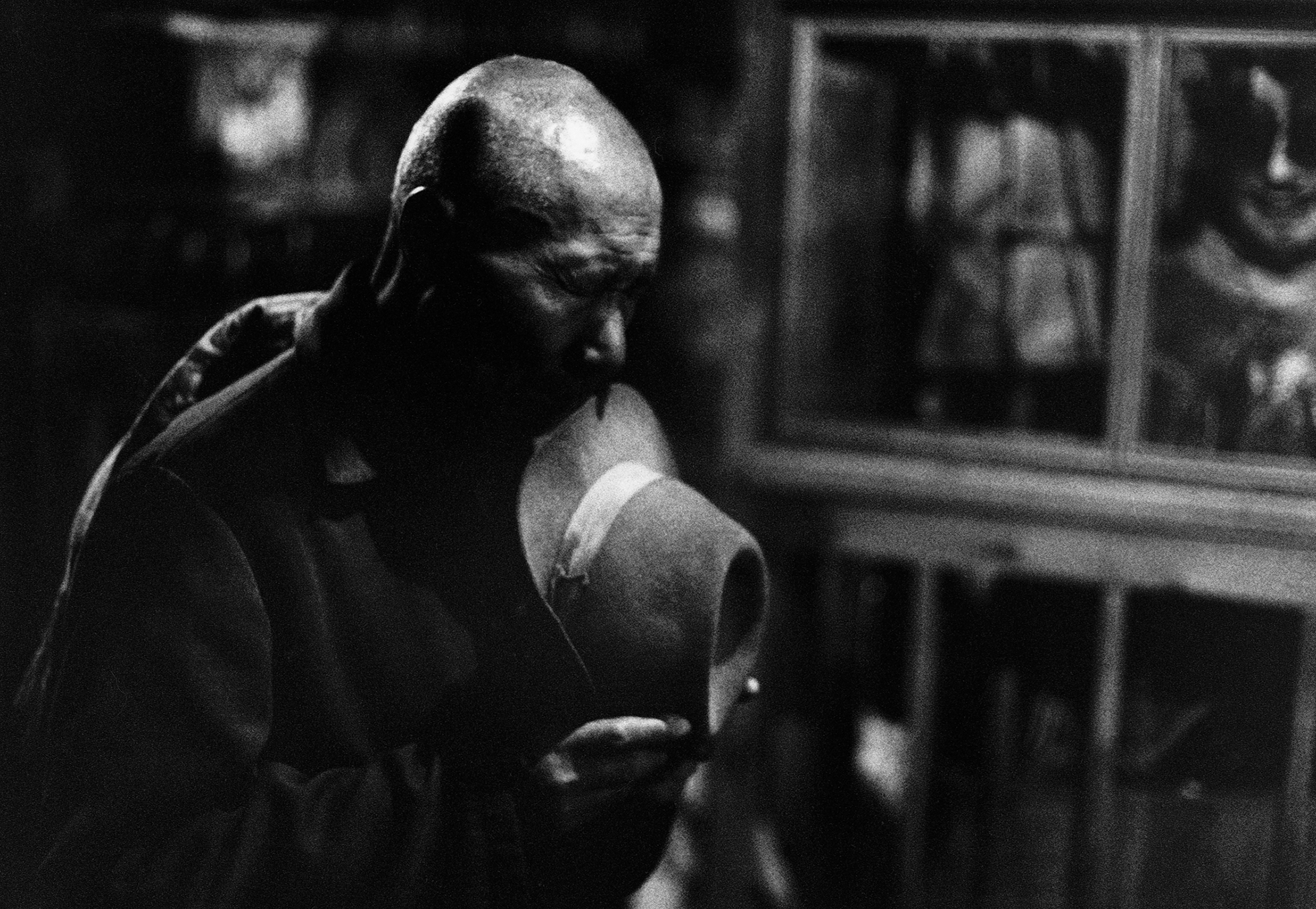

Krech: Now I can tell you one of my favorite stories, about one of the most moving moments in all my studies: It was at a Naikan conference in Tokyo probably twelve years ago. An old man got up and made a presentation. He was a former member of the yakuza, the Japanese Mafia. He had been in the yakuza for pretty much his whole life, until he was arrested and sent to prison.

At the time he was incarcerated, in the sixties and seventies, more than a hundred thousand Japanese prisoners did one-week Naikan retreats, including this man. He had ordered people murdered in the yakuza. He had to look at this during his Naikan reflection, and it was apparently a very powerful experience for him. When he was released from prison, he gave up crime and became a gardener. One day two men in suits showed up. They were from the yakuza, and they told the man that the boss wanted him to come back. The man said, “I’m not coming back. I’m not doing that anymore. I’m a gardener.” They offered him money to encourage him to come back, but still he refused. So they left.

A couple of days later, they returned and said, “We’re here to bring you back.” The man said, “I told you, I’m not doing that anymore.” So they pulled out a gun and put it to his head. He was on his knees, weeding his garden. They said if he didn’t come back, they’d kill him. And he said, “Well, you’ll have to kill me, then.” And for whatever reason, they put the gun away and left. He never saw them again.

I don’t want to give the impression that everyone will make such a transformation. But there is something about looking very honestly at the ways in which you’ve caused suffering, the ways in which you’ve hurt people, that often gets people to change how they live their lives. They come away with a sense of debt.

I mentioned earlier that Yoshimoto was a businessman. He says that those first two questions — “What did I receive from this person?” and “What did I give?” — came from his business background. Every month his company would send out statements saying, “You owe us money,” or, “We owe you money.” In the financial world, we have to know where we stand to the penny. He thought, Wouldn’t it be interesting to reconcile the balance in relationships? Where do you stand in relationship to your wife? To your colleagues at work?

Winter: Do you see the world that way, as a tally of credits and debits?

Krech: It’s not the only way that I see the world, but I think it’s a valuable image to keep in mind, because it colors our attitudes toward people.

If I think of all the things my assistant John has done for me today — going down to the college to put up flyers, picking up the mail at the post office, dropping off a DVD at the video store — it stimulates a sense of appreciation. To be honest, I can’t think of much I did for him today besides give him some money for gas. It’s even more humbling to look at our relationships with our parents or spouse and see how much they have done for us.

Doing Naikan is like doing research on your life. You start by collecting data. Then you analyze your data, and finally you draw your conclusions. I’ve done this for the past sixteen years, and my conclusions are clear: I’ve received much more than I’ve given, both to individual people and to the world in general. Now, I’m not saying this out of humility. This is very data-driven. [Laughs.] I can look at just today and say that I’ve certainly not given as much as I’ve received. If I were to go to bed right now, I would be in greater debt than when I woke up this morning. I think it’s great to be conscious of that. In my selfish, angry, or judgmental moments, I forget it, and that’s why it’s important to keep up the practice, as a regular reminder.

Winter: Could people do Naikan and conclude that the world owes them?

Krech: We have to allow for that possibility, because it’s important that this be open-ended research. You can’t be sure of your conclusion until you’ve collected your data. But most people discover that they are in debt. And once they recognize their debt, suddenly compassion and God’s mercy, which for many are just interesting ideas, become real to them.

I know of a woman who fell onto the track of the Long Island Railroad and was hit by a train, and she did the most extraordinary Naikan on her accident. She listed the people from whom she’d received help: the ambulance driver, the people who’d made the ambulance, the people at the hospital who’d tried to put her back together, her family, people she didn’t know. She followed this with a short list of what she’d given them, and a wonderful examination of the trouble and difficulty that she’d caused. It’s hard to imagine too many things more traumatic than getting hit by a train. Most people would wonder for the rest of their life, Why did this have to happen to me? But she saw her experience in a completely different light. She realized that the world had come to her rescue and given her support in so many ways. [He cries.] As you can tell, these stories are very emotional for me.

Winter: Is this what you mean when you refer in your book to “grace”?

Krech: To me, grace comes from an examination of one’s life in which you realize that you don’t deserve what you’re getting, yet you’re getting it anyway. That is the experience of grace, both practically and spiritually. If you want to put it in secular terms, it’s the difference between seeing life as an entitlement and seeing it as a gift.

Winter: But aren’t we entitled to what we pay for? Didn’t the woman who was hit by a train, in fact, pay for the ambulance service and her hospital visit? How can it be grace when a monetary transaction has taken place?

Krech: If we look at a single transaction, apart from all else, then we can say yes, if you pay for a pair of shoes, you should get a pair of shoes. But this viewpoint ignores the interconnected web of support that makes earning money possible. We are not born with money in our pockets. Just to be able to work is a blessing. Consider how many people can’t work. What if you had a serious disability? Most of us are fortunate enough to have been given an education. How many of us taught ourselves to read and write without any assistance? How many of us paid for all our own schooling?

United for a Fair Economy issued a report called I Didn’t Do It Alone: Society’s Contribution to Individual Wealth and Success. In this report, Warren Buffett, one of the wealthiest men alive, says, “I personally think that society is responsible for a very significant percentage of what I’ve earned.” In our society, many people work hard, but it’s a fallacy to say that someone who has worked hard to get where he or she is in life is a “self-made” man or woman.

Realistically, we must acknowledge that a large portion of our earnings is not earned. It is the result of good fortune and the support of others. So when I buy a pair of shoes, I’m receiving a gift from all the people — my family, my employer, my society — who made it possible for me to have the money to purchase those shoes.

Winter: Do you know of anyone who has experienced problematic results from Naikan?

Krech: [Long pause.] I’m thinking that I should be able to come up with at least one example, just so I’ll seem reasonable. [Laughs.] I keep stumbling over the idea of “problematic results.” If someone comes out of Naikan feeling depressed, to me, that’s not a problematic result. I don’t know offhand of anybody who has been harmed by Naikan. I can think of people for whom there hasn’t been much long-term benefit. The effects dissipate over time if you don’t keep up with the practice. It’s a bit like yoga. You go to a week of yoga classes and leave in great shape, but then you don’t do yoga for two years, and you lose a lot of the benefit of that week. Some people tend to see Naikan as just a philosophy, a way of thinking about life, but really it’s a practice that has to be kept up, just like yoga or meditation.

I think most people who’ve tried it would say that this practice has developed their sense of gratitude and appreciation. With some, myself included, it’s had a dramatic effect on their relationship with their parents or spouse. But there are probably people who would say it was very interesting and they learned a lot from it, but it didn’t take hold of them.

Winter: You’ve written that fallen trees were some of your first Naikan teachers. Could you explain that?

Krech: I was hiking with my dog Rocky up a mountainside in the Shenandoah Valley. There had been some storms in the previous year, and we couldn’t go very far without coming across a huge maple or beech tree that had fallen across the trail. We’d have to climb over it or go around it. After the first four or five trees, it started getting on my nerves. Clearly the trail hadn’t been maintained very well. Is this what my taxpayer dollars are going toward? I thought. Every now and then I’d see the cut end of a tree on the side of the trail, but I had the impression that they were older trees, not recent storm damage. When I got to the top, I couldn’t fully enjoy the beautiful view because I had this little song of resentment playing in my head.

As I went back down, I decided to count how many trees were in my way, and how many trees had been cleared. I saw many cut trees that I hadn’t noticed on the way up. When I finished, I was amazed to find that more trees had been cleared than were in my way.

One of my teachers in Japan — a law professor named Professor Ishii — says that in Naikan what we try to do is temporarily set aside the feelings that tend to color our experience and look at just the facts. Having some clarity about the facts can change our understanding of the experience.

Grace comes from an examination of one’s life in which you realize that you don’t deserve what you’re getting, yet you’re getting it anyway. . . . it’s the difference between seeing life as an entitlement and seeing it as a gift.

Winter: Attention seems to be a theme that runs through your work.

Krech: Absolutely. I begin every workshop by saying, “Your experience of life is not based on your life. It’s based on what you pay attention to.” Imagine you get up in the morning, and there’s no hot water. Then you jump in your car to go to work, and there’s a traffic jam, which makes you late for a meeting. At the office the copier doesn’t work. When you get home, and your spouse asks, “How was your day?” of course you respond, “Let me tell you how my day was. I had no hot water; there was a traffic jam; the copy machine was broken . . .”

And yet you could say, “You know, I had a great day. The coffee maker worked; the car started; there was air conditioning at my office . . .”

Winter: But your spouse would look at you as if you were crazy.

Krech: You’re right. We’ve gotten into the habit of seeing only the problems, because they are more dramatic. That’s what gives a story value. But the cost is that we begin to focus our attention only on problems or traumas or tragedies. All you have to do is watch the news or read the newspaper to see this phenomenon in its most extreme form. As human beings, we mirror that. We complain about the news, and yet we bring that same focus into our own lives.

Winter: So if I’m not my huge, traumatic story from childhood, who am I?

Krech: Good question. If you discard that story, you find yourself without an identity, or rather with an identity that you don’t recognize: someone who got piano and swimming lessons, who went on nice vacations, who always had new clothes, who went to a good school. Can this be my identity? you think. But you know what? It’s a wonderful identity. Adopting an identity that reflects the truth of your life is, to me, one of the most valuable things you can do from a mental-health and a spiritual perspective.

Of course, for some, like that man who was in the yakuza, the truth is that they’ve done a lot of harm in their lives and have been ignoring it. Recognizing and owning up to the truth allows them to speak freely — not with pride, but with a sense of self-acceptance. They no longer have to keep it a secret. Imagine a person who is known for being an immaculate housekeeper, because every time somebody is coming over, he puts all of the dirt and junk into one bedroom. People walk in and see a beautiful living room, a clean kitchen, everything in its place. But he’s always afraid that someone is going to open that bedroom door, and his image will crumble. I think it’s hard to go through life maintaining an image that isn’t really accurate.

This is the problem with the self-esteem movement: it promotes feeling good about yourself, even when it’s not justified. I don’t think people can feel artificially good about themselves without some suffering in the background. It’s much better just to be open and honest.

The people I admire most are those who are honest and self-effacing and don’t try to make themselves look good. For you to sit down today and say, as you did, “You know, this is my first interview,” is so much better than pretending that you’ve done forty-three interviews and you’re an expert. It’s much easier, too, isn’t it?

Winter: Yes, absolutely. [Laughs.] I’m curious: what role do you think attention plays in compassion?

Krech: It’s hard to imagine compassion in the absence of attention. The people I think of as being the most compassionate also tend to be the most attentive to others. It’s a great shock to realize how much of our attention is constantly on ourselves and how rare it is for us to focus our attention on someone else.

If we were trying to develop a course on compassion, the most important element would be to teach people how to shift their attention away from themselves. The third question in Naikan — “What troubles and difficulties have I caused?” — is an invitation to do this. One of my teachers in Japan would say that’s really the essence of Naikan: to be able to put yourself in other people’s shoes, particularly people who get on your nerves, or are messing up, or are mean or evil.

Winter: I’m reminded of the story you relate in your book about Mahatma Gandhi and a thwarted assassin. Could you tell it?

Krech: There were a number of failed attempts to assassinate Gandhi. Supposedly, in one case, the assassin heard Gandhi’s speech and was moved to abort his mission. He fell to his knees before Gandhi and confessed his involvement in a plot to kill the Indian leader. Gandhi’s response was to ask the assassin what would happen to him for failing to carry out his mission. Gandhi was more concerned with what would happen to the assassin than with what had almost happened to him.

If you look at the conflicts in the world today from a Naikan perspective — specifically the conflicts where the United States is involved — you begin to understand why people in other countries would have the attitude they do toward the U.S. When we begin to ask, “What troubles and difficulties have we caused others?” there’s an opening for compassion toward people who hate us, who are fighting against us. The answers for our global situation are the same as the answers for our personal situations. We have to be able to get beyond this intense self-absorption and self-focus.

This issue of outward-focused attention is a central element of Japanese psychology, and yet it’s ignored in Western therapy. Too often we lead people to become even more self-focused. People come in suffering, and their therapy encourages them to become more self-absorbed, which just exacerbates the problem. The psychiatrist Morita’s definition of neurosis is “misdirected attention.” Research shows almost every psychological disorder is associated with self-focused attention. That doesn’t mean that self-focused attention causes the disorder, but it’s an important element of the problem.

I’m more interested in getting people to do what they’re not good at, which is move their attention elsewhere — beyond what’s going on in their feelings, their thoughts, or their bodies. Naikan shifts our attention toward what the world is doing to support us. I can’t answer that first question — “What have I received from my wife?” for example — unless I’m paying attention to what she’s giving me. Just the knowledge that I’m going to be asked that question in a session next week helps me shift my attention. I start looking for those things I’ve received.

As your attention starts to shift, you get outside yourself and become absorbed in the world around you. Anything that pulls us out of ourselves is rejuvenating and healthy. When I’m absorbed in the world around me in some way, I’m not depressed. I’m not lonely or sad.

In the West, we tend to see depression from a medical standpoint, as a disease that’s organically based. We say, “You’re depressive, even if you’re not feeling depressed right now.” But I see depression from a meditative standpoint, as a moment on the screen of consciousness. If you’re not aware that you’re depressed, I would argue, then you’re not experiencing depression. “Depression” is not a personal identity, and there is no permanent cure. Being depressed, neurotic, anxious, lonely, or worried is part of the human condition. The best we can do is create more moments in our life when we’re feeling grateful. You’re not likely to be depressed and grateful in the same moment. We find relief from our suffering in the present moment of our life.

To me, being cured isn’t about being happy. It’s about finding a way to live a meaningful, fulfilling life according to standards that are important to you. Happiness is a wonderful byproduct, but people who go around trying to figure out how to be happy are asking the wrong question — one that ironically creates unhappiness. What kind of society do you end up with if all of us are trying to figure out how to make ourselves happy?

The self-esteem movement . . . promotes feeling good about yourself, even when it’s not justified. I don’t think people can feel artificially good about themselves without some suffering in the background. It’s much better just to be open and honest.

Winter: “The pursuit of happiness.”

Krech: Yes. Do we really want 290 million self-absorbed people preoccupied with personal happiness? Can we really build a healthy society based on everybody being self-focused?

At a community level — from families to nations — these values that seem to be missing from Western psychotherapy are vitally important. We’ve got to start teaching people not just how to be happy, but how to contribute to society, how to have a meaningful life.

Of course not everyone is ready to give up on the pursuit of happiness. It takes courage for people to go through this process. There’s something both attractive and scary about taking a week off to reflect on your life. Many people who come here are in transition. They’ve just gotten divorced, or broken up, or lost their job. They’re in some state of suffering or confusion.

Winter: You don’t go into therapy because you’re happy.

Krech: That’s right. You’re struggling in some way. You’re searching. You haven’t quite figured out the answer. And that suffering enables us to take a step forward in life. The author C.S. Lewis, when asked why God did terrible things to people, said, “To wake us up.”