During our weekly meetings in the Sun office, editor Sy Safransky and I occasionally stray into philosophical territory. One day, knowing that I’d once studied meditation at a Buddhist monastery in Thailand, Sy handed me a couple of videos of talks by the spiritual teacher Adyashanti. At the time, my ardor for the spiritual life was at a low point. My reading of spiritual texts was infrequent, eclectic, and disorganized, and I’d stopped meditating regularly. But late one night, unable to sleep, I watched the videos and was drawn to the simplicity and clarity of this man’s teachings and his playful yet no-nonsense manner.

Adyashanti was born in 1962 in Cupertino, California, a small city in the San Francisco Bay Area, and his given name is Stephen Gray. As a teenager he had a passion for racing bicycles and worked in a bike-repair shop. At the age of nineteen, he came across the idea of enlightenment in a book, and it ignited a desire to experience that ineffable state. He built a hut in his parents’ backyard and practiced meditation there with all the vigor of a competitive athlete, training under the guidance of Zen teacher Arvis Joen Justi. When he was twenty-five, he experienced an awakening, which he describes as “a realization of the underlying connectedness and oneness of all beings.”

For the next eight years he continued to meditate — though he says that all sense of effort and anxiety vanished — and work in his father’s machine shop. In 1996 Justi encouraged Gray to start teaching on his own. He gave his first talks in his aunt’s spare room above a garage to just a handful of students. Sometimes no one would show up. Over a few years the small gatherings grew, until there were hundreds of students in attendance each week. During this time Gray took the name “Adyashanti,” Sanskrit for “primordial peace.”

These days Adyashanti gives talks and weekend “intensives.” He also leads five-night silent retreats, which have become so popular that registration now takes place by random lottery. His teachings seem rooted in the loose, folksy style of the early Chinese Zen masters, as well as in the “nondualistic” tradition, whose basic tenet is that a separate self, distinct from the rest of the world, is an illusion. The nonprofit organization Open Gate Sangha supports his work and sells his books and recordings of his talks (www.adyashanti.org). When he’s not traveling around the country teaching, Adyashanti lives with his wife in the Bay Area, not far from his childhood home.

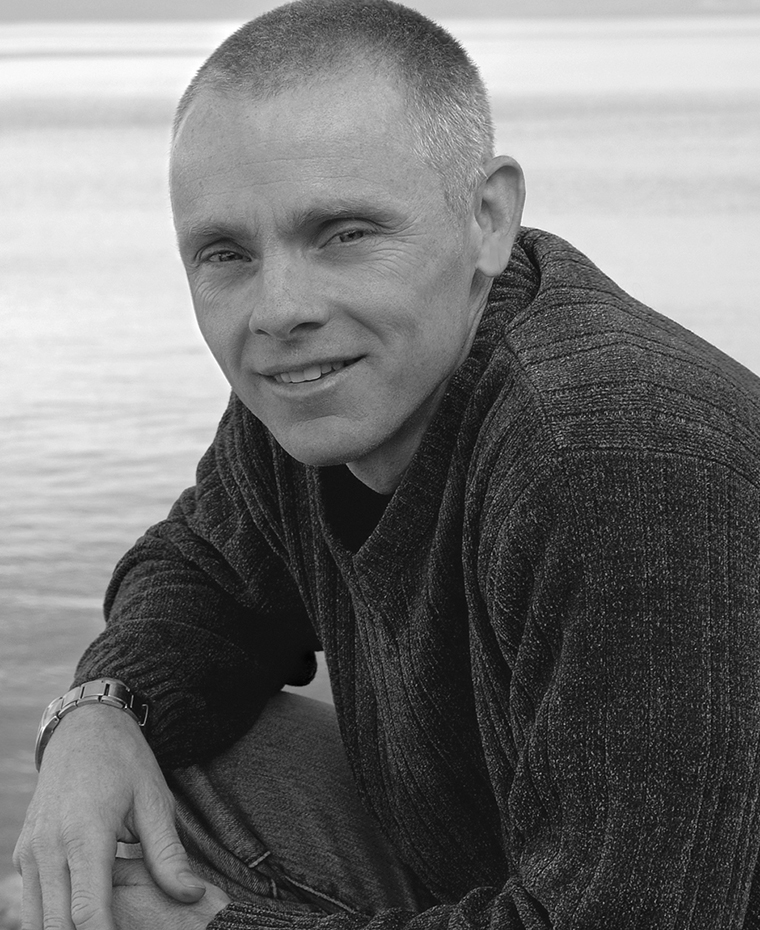

When Sy and I heard that Adyashanti was coming to Asheville, North Carolina, we arranged to meet with him for an interview. On the drive there, as the terrain changed from the rolling hills of North Carolina’s Piedmont region to the steeper slopes of the Appalachian Mountains, Sy and I wondered aloud if Adyashanti would say anything we hadn’t heard before. As we neared the house where Adyashanti was staying, the trip began to resemble a spiritual pilgrimage: we climbed a narrow road that snaked up the side of a mountain, then descended a treacherous, unpaved path, muddy after a recent rain. When we finally arrived, Adyashanti greeted us in a casual shirt, jeans, and sandals, asking us to call him “Adya.” At the outset of the interview, he frequently shifted in his seat and laughed a little uncomfortably. Eventually he relaxed and reclined on the couch, a glimmer in his piercing, crystal blue eyes.

During a pause to change tapes in the recorder, Sy asked Adyashanti about his years as a competitive touring cyclist. “I have a blue-collar body,” Adyashanti said. “It likes to be worked. When I’m at home, I’ll ride my bike two, three, four times a week. I’ll lift weights.” He certainly appeared fit, with veins bulging from his forearms. His demeanor seemed blue-collar as well, with his no-frills attitude and his down-to-earth language, nearly free of spiritual jargon. He said of himself, “I’m a truth guy, not a comfort guy.”

After the interview, Sy and I went to a talk Adyashanti gave at a nearby church. Adyashanti’s talks are unscripted and draw largely from examples in his own life. But on that evening, what struck me most, beyond his words, was his presence between the words. Sometimes he’d pause for a few seconds and close his eyes. His face would become tranquil, and the room would swell with silence.

Following the talk, Adyashanti answered questions from the audience. A woman sitting near us, whose hands had fidgeted in her lap through most of the evening, took the microphone and said she was feeling a tremendous sadness because she feared that she’d never have an awakening experience. Adyashanti asked what her deepest spiritual yearning was. The woman answered, “I want to know God.”

Adyashanti asked the woman, whose name was Nancy, momentarily to stop her search for God and go in search of Nancy instead. “Where is Nancy?” he asked. “What is Nancy? If I ask you where is your hand, where is your foot, you can answer. But if I ask where is Nancy, where is she? She pretends to be the center of this whole life, but where is she? Is this Nancy anything more than a thought?”

“No,” she said.

Adyashanti described the tendency of the human mind to believe in a limited notion of “me,” a separate self at the core of our being. But when we go in search of that “me,” we discover something deeper and more vast. “What is looking through your eyes right now?” he asked the woman.

After a pause she answered, “It feels like life.”

“OK,” he said. “Let’s go with that. It’s life peering through your eyes. So what is life? Is life male or female? When is life’s birthday? Does it have an age?”

“No,” she responded.

“So, at the very center of this thing called ‘you’ is nothing but life,” he said. “It’s not Nancy; it’s life that’s peering through. Now, just for fun, let’s remove the word life. I like the word life. It’s very unspiritual. But since you’re in search of God, what if we replace the word life with God? Isn’t God life, the essence of all existence?”

“Yes,” the woman answered.

“God is peering through right now,” said Adyashanti. “In this moment.”

The woman seemed profoundly moved. “Whoa,” she said, her eyes widening.

“Hang with that for a while,” Adyashanti told her as she quietly took her seat and the next questioner approached the microphone. I noticed that Nancy’s hands had stopped fidgeting and were folded together peacefully in her lap.

— Luc Saunders

ADYASHANTI

Safransky: Let’s pretend that I’m thoroughly unfamiliar with contemporary spiritual vocabularies. How would you describe your teaching to me?

Adyashanti: My background is primarily Zen Buddhism, and yet I would not describe what I teach as Zen. I don’t really see myself as transmitting any particular tradition. My teaching has to do with enlightenment, with awakening to what you really are. It does not matter to me anymore whether I use Buddhist vocabulary, or Christian vocabulary, or Hindu vocabulary. Any vocabulary will do.

The heart of my teaching is to help people question their argument with reality, with what is, and also to help them question their whole notion of themselves.

Saunders: Do you use the terms “awakening” and “enlightenment” interchangeably, or are you talking about two different experiences?

Adyashanti: Awakening is when you realize that what you thought you were was nothing more than a dream, and you perceive the reality outside the dream, what’s dreaming the dream of you. It’s not just a mystical experience. It is actually realizing the underlying unity of all things.

Simply because you’ve had an awakening, however, does not mean you stay awake. Enlightenment, in simple terms, is when you stay awake. If the awakening is abiding, that’s enlightenment. And most awakenings are not abiding — at least, not initially.

Saunders: Awakening and enlightenment sound like head-bound or heart-bound concepts.

Adyashanti: Enlightenment has nothing to do with the head or the heart. Certainly, the head and the heart tend to open up, but that’s a byproduct. Enlightenment is actually waking up from the head and from the heart. It’s waking up from the dream of “me” and seeing the oneness of all things. That’s what I mean by “reality”: that oneness. The truth is that you are that unity. You are not simply a particular person in a particular body with a particular personality; you are that one reality, which manifests itself as all these seemingly separate things.

Saunders: Are the body and physical sensations illusory?

Adyashanti: Yes and no. Ultimately, everything’s a dream, and yet you still have to deal with the body. It’s still there. You can call it “a dream,” but it’s still going to hurt if you bump your head.

Safransky: Most traditions suggest that years of spiritual practice are necessary before one becomes enlightened, but you say that it’s a mistake to look to the future, to see spiritual awakening as some kind of goal.

Adyashanti: One of the best ways to avoid awakening is to let the idea of awakening be co-opted by the mind and then projected onto a future event: something that’s going to happen outside of this moment. Of course, something may happen in the next moment — something’s always happening in the next moment — but the truth lies right here and right now; it is right here and right now. This looking to the future isn’t really the fault of the spiritual practices themselves; it’s the attitude with which the mind engages in the practices — an attitude that is seeking a future end and seeing that end as somehow inherently different from what already exists here and now.

The role of the spiritual practice is basically to exhaust the seeker. If the practice does what it’s supposed to do, it exhausts our energy for seeking, and then reality has a chance to present itself. In that sense, spiritual practices can help lead to awakening. But that’s different from saying that the practice produces the awakening.

The spiritual practitioner is like someone who’s running and is really tired and wants to rest. You could say, “Well, just stop, then.” But they have this idea that they have to cross a finish line before they can stop. If you can convince them that they can just stop, they’ll be amazed. They’ll say, “I didn’t know I could stop and rest.” Or maybe they won’t hear what you’re telling them, and they’ll have to go all the way to their finish line. And after they cross it, then they’ll stop and say, “Wow! It feels really good to rest.” So awakening can come after you cross the finish line in the future, but it’s also possible to find it at any point along the way if you stop for just a moment.

As I see it, reality is always looking for that moment of vulnerability, when we let our guard down. It’s not looking for good people or bad people. Clearly some real scoundrels have had amazing experiences of reality, right? Some are transformed by them, and some aren’t. Reality is not operating on any moral principle. It’s looking for a moment when the seeker is exhausted. It can be prompted by some tragic event: an illness, or the death of a loved one, or a divorce. Reality rushes into the crack and presents itself.

Safransky: Many people say they feel most alive right after having experienced some great loss. Their world stops.

Adyashanti: Exactly. Everything is stopped. Now, whether they stay stopped is another matter. Just because somebody has a difficult experience and feels much more alive as a result, it doesn’t mean they won’t go back to their neurotic ways later. After that initial awakening, there is almost always the work of cleaning up, of the “me” surrendering itself. I usually say that’s the beginning of the second phase of spirituality: what I think of as “life after awakening.” There’s this myth of “That’s it. I have that experience; I hoist my enlightenment flag, and it’s over.” Sooner or later most everybody realizes it’s not that simple. There’s a whole other phase of the spiritual life that happens after awakening, and in some ways it’s more subtle and complex and difficult to navigate. There’s not much written about it, and most of what is written is so old and trapped in tradition that modern people can’t make sense of it.

After that initial awakening, there is almost always the work of cleaning up, of the “me” surrendering itself. I usually say that’s the beginning of the second phase of spirituality: what I think of as “life after awakening.”

Safransky: What method do you teach people for sustaining awakening?

Adyashanti: The first thing I say is: you don’t sustain it. The conscious effort to sustain it is the ego creeping back in. It’s really a complex process of surrender. One of the first things to let go of is the ego’s attempts to hold on to that initial experience. Trying to hold on to it — or to sustain it or stabilize it — is the best way to lose it. For many people that’s a real monkey to wrestle with: how to let go of all the layers of the psyche that are trying to grasp and reproduce and re-create the awakening.

After you understand that, I think there are many methods you could use. I don’t favor any particular one. I try to be sensitive to the person and to feel what they’re predisposed to. One method, of course, is inquiry: asking oneself, “What am I, really?” The point is not to give a pithy, spiritual answer. You’re meant to live with the question, to disassemble all your identities. The question “What am I, really?” allows you to see what you’re not: the false identities and false personas.

That’s one method. With other people, I’ll suggest that they just stop. Just be still. The most important thing is to know the person I’m talking to. What’s their concern? If you don’t know that, you can’t prescribe the right medicine. Some people come to me and say they’re not interested in discovering who they really are. And I’ll say, “Well, what are you interested in? Tell me what your passion is. What’s the most important thing in your life? Connect with that, because that is where your spiritual power is. Once you connect with that, then we can talk about how to work with it.”

The student has to find what’s really important to him or her. Then I can work with it. I think if it goes the other way — if the teacher tells the student what is supposed to be important — it doesn’t work, except by chance, when what’s important to the teacher just happens to be what is important to the student.

Saunders: I recently read an exchange with the Dalai Lama in which a woman asked him, “What is the single most important thing I can pay attention to?” He responded without hesitation, “Routine.” What do you think is the significance of routine in spiritual practice?

Adyashanti: I’ve never thought about it. To tell you the truth, I’m always trying to disrupt routine. [Laughs.] I’m always trying to unsettle the seeker in people, instead of give it something it can feel comfortable engaging in. I’m not saying that my way is right, and the other way is wrong. But what I have found is that spiritual seekers will fall into the routine of the practice, and if it happens to resonate with their deepest yearning, their deepest passion, then that’s great. But often it doesn’t. That’s why I like to connect first with a student’s passion. People will ask me, “How often should I meditate?” I’ll say, “You know what, I have no idea. What are you here for? What do you want? Can you connect with the part of you that will let you know? And then will you follow it?” Most people are so disconnected from their deepest intentions that it takes them a while to find out what they are. They’re afraid to let go of routine and find out what’s really important to them. They’re not sure they’re allowed.

Spiritual awakening doesn’t happen because you master some spiritual technique. There are lots of skillful meditators who are not awake. Awakening happens when you stop bullshitting yourself into continual nonawakening. It’s very easy to use disciplines to avoid reality rather than to encounter it. A true spirituality will have you continually facing your illusions and all the ways you avoid reality. Spiritual practice may be an important means of confronting yourself, or it may be a means of avoiding yourself; it all depends on your attitude and intention.

Death is a myth. Bodies drop, and personalities drop, and your brain no longer functions, but you don’t drop. Death is just an experience that reality has, just as birth is an experience reality has.

Saunders: Do you, personally, have a practice that you follow?

Adyashanti: No. Once awakening has really happened, and once it’s abiding, then there’s no reason to do anything to stay awake. That doesn’t mean that I don’t meditate. I meditate when I feel called to sit in stillness. But there’s no goal behind it, and it’s not a practice.

Safransky: Did you have any spiritual or religious experiences or inclinations when you were young?

Adyashanti: Sure, I had lots of religious inclinations. My favorite movies were always those big biblical epics, like The Ten Commandments with Charlton Heston. I was just mesmerized by religion from a young age. My parents didn’t go to church, but some of my relatives were very religious, and there was a lot of religious talk and debate in the family.

From the time I was a little kid, I had what I guess you could call “spiritual experiences.” They were common for me, and I didn’t think anything of them. I’d “merge” with my dresser drawer, or I’d see a white light at the end of my bed and think, Oh, OK. That was there last night and a week ago. It made me feel good and was comforting, but I didn’t put it into a spiritual context. It was all just normal.

Throughout my teens, I would have days when I’d wake up, and it was as if something totally different were looking through my eyes. I could sense, and feel in a visceral way, that everything was one, that everything I was looking at was somehow myself. I learned pretty quickly that I had to be careful when I was having one of those days, because I would tend to look at people really closely and kind of freak them out.

Then, when I was nineteen, I read a book — I think it might have been by Alan Watts — and I came across the word enlightenment. I had no idea what it was, but something clicked inside me. I absolutely had to know more about it. At that instant, I felt this sense that my life was no longer mine. I didn’t know exactly what had happened, but I knew that some force had woken up inside me, and I just knew the life I’d thought I would have wasn’t going to be my life at all. The knowledge was thrilling, but also frightening.

The funny thing is, as soon as I thought, I have to know what enlightenment is, I stopped having any of those spiritual experiences. They just totally disappeared for about five years. I sought enlightenment the way most people do: I went out and found a Zen teacher and started meditating. It never even occurred to me that I might already have experienced something close to it. Only later did I realize I was having “foretastes” all along the way.

It took about five years of practice to wear down the seeker in me. I strove so hard that I was completely at the end of my rope. For five years I pushed myself until I literally thought I was going to have a major psychological breakdown. I would wake up thinking, Is this the day I end up in a mental ward? One day I went into my little meditation hut in the backyard, and I said to myself, I’m going to break through. Right here. Right now. I put all of my will into it, and within ten seconds it just imploded on me. I said, “I can’t do this.” The knowledge was from my gut. “I can’t do this.” It was like when someone punches you in the stomach and all the air goes out. I was totally deflated. That’s why I often tell people my practice was the practice of failure. I failed. I didn’t progress to a higher state. I beat my head against the wall until I failed. And even then I didn’t give up. I couldn’t be that noble.

Right after I said to myself, “I can’t do this,” everything opened up. I had an awakening of a sort, complete with a lot of the usual spiritual accoutrements. A powerful kundalini energy besieged my body. My heart was beating so fast I thought it was going to explode. I thought I was going to die. In fact, I was sure I was going to die. I thought, Well, if this is what it takes to find out, then I’m willing. I’m ready to go. There was nothing courageous or macho about the thought. In fact, I was surprised that I would actually sacrifice my life in this totally irrational pursuit of something that I didn’t even know much about. As soon as I thought, OK, I’ll die, everything stopped. The energy stopped. I stopped. There was just space. That’s all there was at that moment. I guess you could say I’d disappeared. And then I had this sensation like information was being downloaded into me. You know how you’ll get an insight like Aha! I was having a hundred ahas a second, so many I had no idea what I was aha-ing about. So I sat there until it was done downloading. I couldn’t even tell you to this day what was being downloaded. Then I got up. There just seemed to be no reason to sit there anymore. I got up and bowed to my little Buddha figure, and I burst out laughing. I thought, You son of a bitch. I’ve been chasing you for five years, and you are the exact same thing that I am. It was hilarious to me.

That was the beginning. I was a twenty-five-year-old kid with absolutely no fear. That led to a rather interesting next five years.

Safransky: I’ve heard you say that you were quite reckless after that.

Adyashanti: I was. I didn’t go around thinking, I’m going to do this because I can’t be harmed. It was just a twenty-five-year-old personality with no fear, finding out about life. It’s hard to explain what that feels like. I got myself into situations and relationships that, looking back, I see were a product of my remaining attachments to various identities, combined with an absolute lack of fear, because I knew that death is a myth. Bodies drop, and personalities drop, and your brain no longer functions, but you don’t drop. Death is just an experience that reality has, just as birth is an experience reality has. We’ve assigned death a certain finality, because everything we’ve identified with and everyone we’ve become attached to does die. We become attached to experience, and experience passes. As the Buddha said, it’s impermanent. But I had come upon something that does not pass. It doesn’t die, and it’s not born. It’s not really living. It’s of a whole other domain.

So life became my practice, and mistakes became my teacher. And once again I experienced failure after failure. It was humbling, even humiliating. I put myself in situations where my self-image would get crushed. Looking back I could easily say, “Boy, I made a lot of dumb mistakes.” But I needed to do it that way. I wasn’t going to let go of those identities on the meditation cushion. It would have been nice if it could have been contained in this safe environment — bowing and meditating and meeting with the teacher — but it often doesn’t work that way. Spirituality is much more of a bloody mess than we like to admit.

So I bumbled around and made a lot of mistakes, and my many identities got stripped away unceremoniously and sometimes in public, which was even more valuable. The most glaring example was when I got into an unhealthy relationship. It was just one of those relationships where I thought I could help this person, who appeared to need a lot of help. It was very dysfunctional, and it drew on every helper identity I had, every I-can’t-help identity, every fear I had of what somebody might do to themselves because I couldn’t help them. After a year and a half, I started to see that it was going down a dark hole, and I didn’t see any light at the end of the tunnel, only more darkness.

To end a relationship, most people just get angry and say hurtful things to each other. We often use negative emotions in order to separate from people. But I couldn’t do that. I think I had seen too much spiritually. Anger just wouldn’t work for me. I couldn’t get a sense of blame going. I realized the only way I could extract myself was to start to pay attention to what I knew was true and to act on it, no matter what. Bit by bit, I started to do that. Of course, to do that, I had to get outside my personas, my personalities, my self-images. I had to get outside all of that and just act on truth alone, no matter what it looked like, no matter the reactions I got. That’s what I started to do. When the relationship ended, I felt completely stripped of any self-image, as if it had all been torn away and cast on the ground. I didn’t know who I was anymore, because I could no longer pretend to be anybody; I knew any persona I tried on wouldn’t be true. I saw the phoniness of it, not in a spiritual way, but in a human, visceral way. It was an amazing relief.

That whole situation was an intense, quick purification. Maybe I could have done it on the cushion, but I’ll bet it would have taken twenty or thirty years. I got on the spiritual fast track, and the fast track isn’t always pretty. Fortunately my mistakes didn’t do any permanent damage to me or anybody else. That was really lucky.

Safransky: Then what happened?

Adyashanti: One day, when I was thirty-three, something happened without any emotion, which, for me, was absolutely necessary: I heard the call of a bird outside, and a thought came up from my gut, not from my head: Who hears this sound? The next thing I knew, I was the bird, and I was the sound, and I was the person listening; I was everything. I thought, I’ll be damned. I had tasted this at twenty-five, but there had been so much energy and spiritual byproduct. This time I didn’t get elated. It was just factual. I got up and went into the kitchen to see if I was the stove, too. Yeah, I was the stove. Looking for something more mundane, I went into the bathroom. What do you know: I was the toilet, too. Paradoxically I also realized that I am nothing, less than nothing. I am what is before nothingness. And in the next moment even that disappeared. The “I” disappeared completely. All of this — the oneness, the nothingness, and beyond both oneness and nothingness — was realized in quick succession. It all exists simultaneously.

This was a sort of pure, unemotional, clear perception of reality that got more and more ordinary over time. After a while, you realize that everything is one, and you stop jumping up and down about it. It becomes a part of everyday life. At this point, there’s nothing spiritual about it to me. In fact, it sort of took away my “spiritual” life, which is sometimes necessary to have, but is sort of an imposition, an addition onto life. I think if spirituality, that imposed structure, works well, it eventually disappears.

Safransky: Somehow it’s easier to imagine someone who’s awake or enlightened experiencing states of joy or bliss, rather than states of depression, anger, and confusion. What is the ordinary range of emotion for you, and how does it differ from what you experienced before these awakenings?

Adyashanti: No emotion or experience is necessarily excluded from my life. Do I ever get angry? Sure, I get angry. Awakening shows us that emotions are illusions — but that doesn’t mean they will cease to arise. That doesn’t mean we’ll never have another conflicting thought. I find that the awakened consciousness has an innate tendency to look into anything that feels discordant: the more awake I became, the more sensitive I became to any discord in the psyche or in the body. Spirit actually seems to be interested in discord. Since there’s nothing to be lost, there’s no fear you’ll be seen or found out.

Enlightenment has nothing to do with the elimination of certain human experiences. The difference for me is that there is this deep, underlying sense of well-being and freedom, a lack of self-consciousness. The mind that’s always measuring, How am I doing? Do they like me? — that receded. For a while, its absence was baffling. Even after the event that started with hearing the bird, much more conditioning had to be cleared out, a tremendous amount. There were years of uncovering anything that remained.

Saunders: So there is still transformational work to be done after awakening, in order to become fully enlightened.

Adyashanti: I wouldn’t call it “transformational work.” It’s just paying attention to what is. There’s no time when you’re so awake that you get to stop paying attention and go back to sleep again. I’m still capable of having a thought that’s untrue move through my mind and emotionally grab me for a second. Seeing that these thoughts aren’t true is a continual process. You can’t just understand it with your mind, though. You’ve got to see it from your whole being. And it seems that, the more you see through these thoughts, the less often they visit, and the more you can actually express reality through your actions, through your relationships, and through who you are as a human being. I guess one could call that “transformational work,” but when there’s real awakening, it doesn’t feel like work.

Once you see reality, once you know it, you know the whole of it. In that sense, there’s no deepening. But, at the same time, reality is like a bud that keeps opening. The petals keep revealing themselves. It’s not as if that bud becomes something that it wasn’t before. It just keeps showing its potential. Reality reveals itself more and more over time. I can’t see a limit to that, since we’re talking about something that’s inherently without limit. Who knows, though. I’m always open to being surprised. [Laughs.]

Safransky: There are so many spiritual paths available today, so many old, esoteric secrets that are no longer secrets.

Adyashanti: Yeah, every secret is available for $10.95 at the local bookstore.

Safransky: There’s a tendency for people to take a little from here and a little from there. Do you see that as problematic?

Adyashanti: It can be. With an endless amount of spiritual window-shopping, there’s a danger we may never settle down and really get to the deeper spiritual process. I see that when I teach. There are some people who rush to see every new teacher in town, which can have its drawbacks, because sometimes those people are not getting down to the serious task of personal inquiry.

Other people, however, seem to be able to find what they need here and there and actually use that information for a deep spiritual process. Like everything else, it depends on the person. But too much window-shopping is a danger of a spiritual climate where everything is available, where you don’t have to beg at the temple doors, or sit at the feet of the master for three or four years, or sacrifice anything.

I heard the call of a bird outside, and a thought came up from my gut, not from my head: Who hears this sound? The next thing I knew, I was the bird, and I was the sound, and I was the person listening; I was everything. . . . Paradoxically I also realized that I am nothing.

Safransky: Many masters turn out to be abusing their power: conducting inappropriate financial dealings or having sex with their disciples while advocating celibacy. Why do you think that happens?

Adyashanti: I can take a guess. There’s a lot of power inherent in enlightenment — or the perception of it — and spiritual power is no less corrupting than any other power. In fact, it may be even more corrupting.

I remember the first time I became conscious of this: I started teaching at thirty-three; most everybody was older than me, and more educated, and smarter. They had better jobs and all that. As I was driving home from teaching one night, it suddenly hit me: I could go in there and say almost anything and make them believe it. I saw, all at once, the incredible frailty of human beings. And I understood how intelligent, well-educated people can get involved in cults and the most ridiculous ideas: when we are in the grasp of ego, we’re extraordinarily vulnerable. As soon as I realized this, something else arose, which was this extraordinary distaste for it. That sort of power isn’t a pleasant thing to have. Now I look back at my teacher, Arvis Joen Justi, and see that her most important transmission to me was her integrity, because it gave me that distaste for power and influence. I can only guess that some people, even people with the best intentions, start to find that power enticing.

When you’re a spiritual teacher, you’re living in the projections of people around you. They have a tendency to see you as godlike, and that is not a healthy environment for anybody. But a spiritual teacher, by nature, has to exist in it. I’ve found that the more you try to correct this perception, the stronger it becomes. People just think you’re even better, because you’re not like all the teachers who are encouraging their students to see them as demigods. There’s no way around the projection game, and the potential is always there for it to corrode my integrity. I’m not immune to that. In fact, as soon as I conclude that I could never take advantage of people, it’s already started. It’s a subtle thing that can easily grow as time goes on, because there’s usually not someone around to say to the teacher, “Hey, this isn’t right.” Spiritual students are almost encouraged to think that because the teacher is an enlightened being, he or she knows everything. So people check their good sense at the door. What I tell people is that if you’re seeking enlightenment, your good sense is vital. In fact, you’re going to have to learn to trust it more and more. I think people actually know early on when something’s off about a teacher, but they think they must be wrong, because an enlightened person can’t do any wrong. And that’s not true. Enlightened people can do wrong. They can do harmful things. I think sometimes they don’t know it themselves.

My teacher told me, “There are lots of temptations out there. If you ever think you can’t handle those temptations, stop before you do something stupid.” That was a promise I made to her. We shouldn’t make the assumption that lust or greed or corruption could never emerge in us. It clearly can. Humility is always the best protection against being corrupted by power.

Safransky: Didn’t taking the name “Adyashanti” reinforce a certain sense that you are an enlightened holy man?

Adyashanti: Oh, absolutely it did. It’s sort of a ridiculous-sounding Eastern name.

Safransky: The spiritual teacher Ram Dass once told me he wanted to go back to the name Richard Alpert, but his publishers wouldn’t let him, because then he wouldn’t sell any books.

Adyashanti: [Laughs.] I always tell people to call me “Adya,” and leave the “shanti” part off.

Safransky: Do you ever regret having taken the name on?

Adyashanti: No, because it’s a vital and mysterious part of the teaching process that I don’t really understand. I resisted it for a long time, and when I finally decided to take the name, I literally didn’t tell anybody. The next time I taught, a whole new group of people showed up. The average age almost doubled, and their spiritual maturity probably tripled. I knew somehow that it was linked to my taking this name, even though nobody knew about it yet. That’s why I say I wouldn’t go back and change it, although admittedly it’s a bit embarrassing. [Laughs.]

Once you see reality, once you know it, you know the whole of it. . . . But, at the same time, reality is like a bud that keeps opening. The petals keep revealing themselves. It’s not as if that bud becomes something that it wasn’t before. It just keeps showing its potential.

Safransky: You don’t look very embarrassed.

Adyashanti: Over the years, I’ve learned to play with it. It’s just about as funny as any other name. When people get to know me, they see I have a certain casualness, and they kind of join in that. They know they can play with me and joke with me, and we don’t have to take each other too seriously. I guess it all works out, even with the big, fancy name.

Saunders: Is that use of humor and play an intentional part of your teachings?

Adyashanti: It’s not intentional. I just see some things as profoundly funny.

Saunders: So it emerges more from your personality.

Adyashanti: Yeah, that’s more it, although I think it’s part and parcel of being awake that you don’t take things too seriously. The thing you probably take the least seriously is yourself. I’ve heard enlightenment described as the “restoration of cosmic humor.” I think that’s a wonderful description. If you think you’re awake, but you don’t have a sense of humor, you’re probably not as awake as you imagine yourself to be. Humor comes with the knowledge that all is well.

Safransky: One of your talks on your website is titled “Gift for a Dying Friend.” You make a distinction between expressing our love for someone who’s dying and showing our attachment to them. Is there anything else you would say to someone facing the loss of a loved one?

Adyashanti: Usually, when I meet someone who’s in that situation, they’re trying not to grieve. Maybe they’re trying to transcend grief, or maybe they’re afraid of the enormity of it. So I often encourage them to open to the grief, and I let them know that grief is not unenlightened. It’s a natural way for our systems to cleanse themselves of painful emotions. It’s true we can get stuck in grief. We can become fixated in grief. But more often I find that people don’t open fully to it. When they finally do, what comes up is a tremendous sense of well-being. I don’t mean the grief goes away, but there’s grief and a smile at the same time. It’s just like true love. True love is not all bliss. As my teacher said, true love is bittersweet, like dark chocolate. It almost hurts a little bit. Ultimately all emotions contain their opposite.

When people are in the midst of grief, sometimes, if I think they’re ready for it, I’ll encourage them to think about what’s happened to their loved one: They’re gone. Everything you know about them is gone. Their appearance is gone. Their body is gone. Their mind is gone. Their persona is gone. There is nothing to relate to anymore. It’s all gone. Now, is there anything left? That’s the actual truth of them: what’s still there after a person is gone.

Years ago a woman wrote to me and said her mother was dying of Alzheimer’s, and it was tearing her up. The mother she knew wasn’t there anymore. I wrote her back and said, “Why don’t you sit down next to the bed where your mother is and just reflect on the fact that the person you knew is gone. Her mothering function is gone. The way she used to interact with you is gone. Her personality is gone. It’s all gone. Just sit there for a moment and allow all that to be gone, and see if there’s not anything else. Maybe that wasn’t all there was to your mother.” The woman wrote me back about a week later and said she’d sat next to her mother and let her disappear and thought, Is there anything left? All of a sudden, she knew there was an amazing presence that only took the form of her mother. And she knew that’s what her mother was; that’s what she’d always been. It brought this woman great relief. Then she took it to the next level and thought, If that’s what my mom is, I wonder about me. And she found she wasn’t the person she’d been pretending to be. She was the same presence.

Death is like that: it takes away appearances. It’s OK to grieve the loss of appearances, but it helps to recognize the presence that’s beyond those appearances.

Saunders: What do you think happens to individual consciousness after the death of a body?

Adyashanti: The question presumes that there is such a thing as individual consciousness. Awakening shows you that there isn’t. The mind creates the illusion of individual consciousness to convince us that this awareness is ours, that it belongs to us. I imagine that, after the death of the body, it’s very difficult to maintain the illusion of individual consciousness. But who knows? We’ll see. I’ll give you a phone call if I can. [Laughs.]

Safransky: You said earlier that the awakened state is not a reprieve from grief or anger or any human experience. So how are negative emotions to be handled?

Adyashanti: In my case, grief and anger and other negative emotions don’t happen anywhere nearly as often as they used to. But I’ve found that the truth of who we are can and does use all the emotions. Anger is an energy that can be used in a wise way. Mostly we experience anger out of divisiveness, a battle between two opposing forces. But one can experience anger that comes from wholeness rather than division. Once you’ve experienced it, you know the difference. We don’t need that energy very often, but when it’s needed, it will come.

Safransky: How about violence?

Adyashanti: I haven’t experienced violence as a spontaneous manifestation. To me, violence is inherently self-centered. The first Buddhist precept is “Do not kill.” But then there’s the ethical conundrum: What would you do if you had the opportunity to kill Hitler before the Holocaust? If you kill him, you’re karmically responsible for murder. If you don’t kill him, you’re karmically responsible for the deaths of 6 million people. So even to say, “I will not kill,” could be seen as violent, if 6 million people are going to die because you couldn’t pull the trigger. This is an extreme example, but I think that in small, less dramatic ways, these kinds of situations do arise in life. So I can’t say that there is absolutely never a moment when violence is called for.

The more awake we get, the less we see life in absolutes. Enlightened action doesn’t arise from absolutes. It comes from wholeness moving through you. You can’t say what wholeness is going to do. It might do one thing through one person, and another thing through another person. It might move through the Dalai Lama and cause him to say, “We will not fight the Chinese,” but it could move through another enlightened being who says, “We’re not going to let the Chinese in here, because they’re going to massacre people.” It could have gone either way with an enlightened being — at least, in my view. Of course, that’s more ambiguity than most people are comfortable with.

Safransky: Could killing animals to eat them come from wholeness?

Adyashanti: Sure. Life is killing. If we eat a vegetable, we’ve killed it. If we eat an animal, we’ve killed it. To be a living organism is to kill. There is no life without death. When we die, we’re going to be nutrients for something else.

I don’t see life as “anything goes,” but I have seen wholeness move through different people in different ways. That’s why I’m always talking about action that comes from wholeness, not from division, nor rejection, nor grasping, nor pushing away. What motivates us when we’re not pushing or grasping, not relying on conditioned concepts of right and wrong, good and bad? Is there something else that can move us? And what is that? Action that is an expression of a clear and undivided state of consciousness is what the Buddha meant by “right action.” To exercise right action we must be functioning from a place outside of all egoic self-interest. We must be awake within the dream and be able to express that perspective.

Safransky: What feelings do you experience when you watch the news or read about what’s happening in the world?

Adyashanti: Usually a whole conglomeration of feelings at once. Sometimes there will be a bombing, and I’ll feel the pain of it. That’s part of being enlightened, I think: you’re open to the suffering around you. You can experience it. Those kinds of emotions will run through me, and also an underlying sense — an almost irrational sense — that all is unimaginably well. It couldn’t possibly be more well. And, in the midst of its being totally well, there can be pain. It’s not that one erases the pain. I think if the sense of well-being is immature, it does erase the other. Sometimes you hear people say they’ve had the perception that all is well, and you can feel the ego hiding behind it. It’s comfortable there. It feels good. It’s nice. In my experience, the truth is that all is well, and, at the same time, all isn’t well. I can’t explain it, but it doesn’t feel like a paradox to me. It doesn’t feel contradictory. It just feels like that’s the way things are.

To me the sign that someone is really starting to feel the truth is when they have a sense of well-being and fearlessness, and yet they still feel the suffering of others, and they still respond. They don’t just hide out in heaven. As one Buddhist teacher said, “Everybody knows not to get stuck in hell, but not everybody knows not to get stuck in heaven.” That’s one of the temptations of a spiritual life. We do enter the heaven realms, the untouched realms, the deathless realms, the fearless realms, the all-is-well realms, and they have a truth to them. But the truth is beyond heaven and hell. It’s beyond “all is good” and “all isn’t good.” It’s the third thing that holds both of these without any contradiction.

Safransky: One of the ways into that heaven realm for some people is consciousness-altering drugs. Have you had any experience with those?

Adyashanti: In my younger days I tried them a couple of times. It was interesting, but I had the sense, even then, that I was sneaking into the temple without permission. I’m not saying it’s wrong to take drugs. Some people have transformative experiences; for many it starts them down the spiritual path. But I instinctively knew that this wasn’t the real thing, but rather just an interesting vacation. My subsequent experiences showed me that you can enter similar realms through various disciplines and practices, but those realms, too, are impermanent. They come and go. They have the sense of ultimate reality, but they’re not. There is something deeper that is manifesting them. Both drugs and spiritual experiences are easy to get caught up in. There are probably as many spiritual-experience junkies as there are other kinds of junkies. They will spend all their money and follow any goofball anywhere if that goofball promises them the experience they crave. So spiritual experiences are fine. They’re part of the path, and they’re very pleasant, but don’t mistake them for reality.

Safransky: So that sense of well-being that underlies everything — that’s not a spiritual experience?

Adyashanti: I call that a “byproduct” of the realization of truth. There are other byproducts: a sense of happiness or freedom; being prone to fall into silly reveries at the drop of a hat. Yet, as soon as we think those byproducts are the awakening itself, we become attached or even addicted to them, and we miss their source. So I’m not grounded in those experiences. I’m not grounded in the experience of well-being. In fact, I couldn’t care less about how I feel. It just became irrelevant at some point. To be rooted in something deeper was . . . I can’t say it felt better, because it didn’t. It just has an effect on you. It makes it easier not to be attached to things, because you see them as irrelevant.

Safransky: Psychotherapy is one way people try to understand themselves better. What are its advantages and limitations?

Adyashanti: I would guess that the vast majority of people who come to see me, or any other teacher, would probably do well with a little help from a good psychologist. I think psychologists can offer tremendous aid to people who are trying to transcend their conditioning. Going to a psychologist is not the only route, however. There are other ways to deal with conditioning, too. Somehow or other, the conditioning will need to be addressed, either before awakening or after awakening. You can have direct experiences of deep reality, but if you have too much psychological conflict, or your ego is still too fractured and not functioning coherently, it will keep holding you back. Ego, by its very nature, is never completely coherent, but well-functioning egos are nicer to be around.

Saunders: How do you define “ego,” and what happens to it upon awakening?

Adyashanti: To me, ego isn’t this thing that we need to get rid of. It’s like a verb: a phenomenon, a movement of thought that alters and distorts perception. It causes us to see ourselves as occupants of a world that is quite distinct and different from us, and to see everybody and everything in that world as separate from us. So that movement of mind and belief is what I would call “ego.”

After you awaken, you no longer identify with ego. You don’t see it as real. All the ways that it divides us no longer seem real or even rational, but rather like forms of insanity. Statements about the ego “disappearing” miss the mark. The ego is still there; you just see it to be an illusion.

Saunders: How can we avoid deluding ourselves about our spiritual progress and underestimating the power of our conditioned human impulses?

Adyashanti: You’re on your own there. You’re better off if you have your integrity intact, but if you’re determined to fool yourself, you will, and no one will be able to save you from doing it. So take responsibility for yourself and don’t put it on others. If you do that simple thing, you will find it harder to delude yourself and underestimate your impulses. It all comes down to your intention. If you have the inner integrity, it will protect you.

Safransky: How has being married helped you on your path?

Adyashanti: I’m not exactly sure. I can tell you I’m happy to be married. I enjoy spending time with my wife. As a teacher, I find it’s nice to have someone who doesn’t relate to you as “the teacher.” I can stay in this teaching environment only for so long before I need to take a break: a walk in the woods or an encounter with someone who doesn’t like me. I don’t know how someone could possibly be “the teacher” all the time. I’ve told my wife, and also my mother, “Look, I am counting on you to keep an eye on me as a teacher. If you ever see me going down some avenue that you think is wrong, you tell me.”

Safransky: Has either of them ever waved the red flag?

Adyashanti: Not so far. But I think they would. They’re not so enamored of me that they wouldn’t speak up.

To answer your question about how marriage has helped, I have to say that the second awakening I told you about happened shortly after I’d gotten married. Funnily enough, it happened on St. Patrick’s Day, and my wife comes from an Irish family. Looking back, I see there was a sense of stability in my life because of our marriage. Something in me was more able to relax and really let go. But marriage isn’t the answer to everything. When we got married, I thought, This is better than I ever hoped it would be. Then I thought, It’s not enough. It was enough in terms of the relationship. It was more than enough. But, in that deepest place within me, I realized that it wasn’t enough, and it never will be, not until whatever is inside me, spiritually, is completely, absolutely addressed. That realization was useful, too. In the back of our mind we often hold out this hope, If I could just meet the right person . . . But then, even if it’s great, it’s not going to be enough.

Safransky: Your retreats are so popular you’ve started holding a lottery to decide who can get in. How have you dealt with that success? You don’t look burdened by it.

Adyashanti: Fortunately I have good people to support me. This organization, Open Gate Sangha, has grown up around what I do, and I actually do less organizing now than I did five years ago. My support staff takes care of it a whole lot better than I ever could. I am, of course, making sure that this truth that we talk about in the abstract is reflected in how we’re running the whole operation. It’s a challenge to translate spiritual truth into a policy that you can put on paper or talk to people about.

The success has been pretty surreal. I just never dreamed of it. My teacher taught in her living room in Los Gatos, California. Almost nobody knew about her. I don’t think she ever had more than fifteen students. She didn’t wear robes. So I thought I would teach in my living room on the weekends. I still walk in the door of a retreat center and think, Why are there more than twenty-five people here? Why are all these people coming to see me? I’m really just a voice for this. This isn’t about me. And the bigger it gets, the more obvious it becomes that it has nothing to do with me. I just happened to fall into the position of being the voice for something.

Saunders: Some spiritual teachers talk about a new state of consciousness for humanity on the horizon, an evolutionary leap, a New Age. Do you see any evidence of this?

Adyashanti: Not much. [Laughs.] In fact, I see a lot of evidence to the contrary. Of course, I really hope I’m wrong.

To equate enlightenment with the evolution of consciousness for humanity is to absolutely misunderstand what enlightenment is all about. And it’s nothing new. People have been saying for thousands of years that we’re on the cusp of “a new state of consciousness,” and they will for thousands more. By and large, it is a mechanism for putting ourselves to sleep rather than waking up. Most people who think they’re part of the greater awakening of humanity are actually just aggrandizing their own egos. The truth is we don’t know the future. We can’t know the future. One of the best ways to stay asleep is to wait for a future when we’ll all be awake. But, like I said, I hope I’m wrong. If the whole world wakes up tomorrow, I’ll be glad that I was wrong.

I’ve heard enlightenment described as the “restoration of cosmic humor.”. . . If you think you’re awake, but you don’t have a sense of humor, you’re probably not as awake as you imagine yourself to be. Humor comes with the knowledge that all is well.

Safransky: What’s the single most important piece of advice you would give to someone who wants to awaken?

Adyashanti: Get in touch with what you really want. What does awakening mean for you? Do you want it because it sounds good? Then you’ve borrowed someone else’s idea of it. What is it that’s intrinsic to you? What’s been important to you your whole life? If you touch upon that, you are in touch with a force that no teacher or teaching could ever give you. You are quite on your own in finding it. No one can tell you what that is. Once you feel it, once you’re clear on it, everything else will unfold from there. If you need a teacher, you’ll find one. If you need a teaching, you’ll bump into it, probably in the most unexpected way.