He was bringing coffee in five minutes, at 6:30. She’d been awake for an hour and now sat on the hardwood floor, blowing smoke into the fireplace so her kids wouldn’t smell it. She’d picked up her cigarette habit again since his last episode, the one that had led to his moving out.

The coffee was their current routine. He would get up early at his new apartment, go to the coffee stand, drive to the house, and tap on the door before opening it, carrying the two cups of coffee in a brown drink holder. He’d hand her hers, then follow her into the family room. They’d sit, he on the end of the leather couch and she in the chair adjacent, and sip coffee and talk until the kids woke up. This is really good, she’d say, and he’d nod, sipping. But the arrangement was only a month old now, so it didn’t feel entirely real. It didn’t feel like something she could count on.

The old routine still played in her mind, the one she’d performed so well for nearly twenty years: tiptoe and placate, fix breakfast, lay out his watch and wallet on the kitchen table, start his car when he went up to brush his teeth, then give him a kiss at the door. After he’d left for work, she’d have peace for a few hours, she and the kids, until they went to school. The evening performance would consist of cold beer and TV and more cold beer and the kids’ homework and dinner and wine. Then a blow job. Or intercourse. Or both.

When she’d kept it up just right and juggled the bills and the chores and his moods with a smile, it hadn’t been too bad. But sometimes the performance had changed in ways she couldn’t anticipate. He would shout unexpectedly or try to foul her up, throwing a shoe or a dinner plate.

She tossed her cigarette butt into the fire. The fire used to be his responsibility. He used to get up and tend to it in the middle of the night instead of running the furnace till morning. It was something they had enjoyed, being the only people on their city block who had firewood delivered, their kids the only ones among their friends to know how to stack a cord of wood so that the pile was stable.

Now that he was sleeping at an apartment, the fire was hers. She let it burn out at night, then built it in the morning. She liked doing it her way.

She lit another cigarette, wishing she had her coffee to go with it. But just the coffee, not the coffee bringer, not him.

She knew she’d given her last performance when the older two heard the show. They’d come downstairs after they’d heard the garage door open and were standing on the other side of the kitchen door — not that she knew that at the time. She was in the garage, defending herself against the latest accusations that she was hiding money, that she was staying with him for insurance coverage, that she would soon leave him for her “career.” (This last barb referred to a part-time job she’d taken, answering phones for a property-management firm, to help with family expenses.) Her performance was weak and stilted that night. There wasn’t enough slack in the rope to keep him tethered to her without its snapping in two. He finished by declaring, This is it. My lawyer will be calling. She nodded and went inside, locking the door behind her, fully expecting him to break it down.

The older two were standing in the kitchen when she came in, their faces expressionless, their arms limp at their sides. What’s the matter with Dad? her son asked.

She wiped her face, not knowing when she’d started to cry. He’s not doing too well, she said.

Again? asked her daughter.

She looked at them then — the boy, seventeen, so tall and thin; the girl, petite, her rounded shoulders in relief against her older brother’s angular build — and thought of all the times she’d performed flawlessly, making certain they hadn’t seen or heard any of it. It isn’t good, she said.

Divorce? her daughter asked.

It looks like that might be a possibility, she said.

Her son stood silently, then turned and walked to his room. Her daughter followed, around the corner to hers. After she’d heard both their doors shut, she stepped into the family room and sat in front of the fireplace. Only cinders from the last log remained, glowing red amid the charred black.

She threw the butt of her second cigarette into the flames and leaned back to look at the clock. He was half an hour late. She stared into the fire. He was never late, not after that last show; these were the days of convincing and pleading and perfect behavior. He was seeing his psychiatrist again. He would never have another drink, not a single beer. He would stay in an apartment around the corner until she trusted him again. He was taking his medicine.

She knew that last part was true because she often picked up the prescriptions for him, yellow and blue and white pills. The doctor was testing different combinations, trying to get the balance back. She thought about the pills: the quantities; the combinations; the effects, known and unknown.

They’d met during the summer twenty years earlier and had dated long-distance during his last year of college. After six months of two-hundred-dollar phone bills, they’d gotten engaged at Christmas and married six months after that. She became pregnant with their son on the second day of their marriage. She’d just begun to show when he did it the first time: the fight about nothing, in the middle of the night, after he’d been drinking. She lay beside him, nerve endings tingling, listening to the rambling accusations and threats. She stayed awake throughout the night, listening to his snoring and restless mumbling. I can’t ever do that again, she said to him in the morning.

Do what? he asked.

That business last night, she said. I don’t know what it was, but I don’t do that. I can’t do that.

He looked at her, his eyes serious. I’m sorry, he said. I don’t know what gets into me.

Their son was born, and, thirteen months later, their first daughter. She gave up her job, she ironed his shirts, and she learned to make a perfect sirloin-tip roast. When the kids were three and two, it started again, fiercer than before, the beer on his way home and another right after he walked through the door, then the fists through walls and tools hurled across the garage. She looked at the kids’ room — two cribs — and the back seat of her old Toyota — two car seats — and the corner of the kitchen — two high chairs — and she knew what her only option was.

The third cigarette wasn’t as satisfying as the first two; she needed her coffee. He was now forty-five minutes late. Where was he? Perhaps he’d simply overslept and was still at his apartment. She’d been there a couple of times, helping him set up and going to the dollar store for sponges, a toilet brush, and a silverware holder. But she wouldn’t go there now. She couldn’t have gotten inside even if she’d wanted to; she didn’t have a key. I’ll get you a key, he’d said. You should have one.

OK, she’d said, still performing, because you didn’t tell someone you didn’t want a key when they offered it to you. You didn’t tell them you wanted your own key back.

It wasn’t as though she hadn’t tried. There’d been plenty of trying over the years, psychologists and psychiatrists and well-meaning friends. She liked to talk to her mother best, because her mother understood. She’d had her own difficult marriage and had left her husband after twenty-three years. Left him for what remained of her own life, she said; for a little happiness, a chance at real love. While her mother had moved into her new world, her father had moved in with his own mother, sleeping on the fold-out in the sewing room. And when she’d called her father to see how he was doing, he’d cried. Her husband had wept, too, as she was leaving his apartment after getting his kitchen squared away. The men cried; the kids went to their rooms; the women carried on. Would the professionals say that was for the best? Would they say that the most loving thing you can do for another person is to let him experience the consequences of his actions?

At 7:30 she got up and made a pot of coffee. She thought about her husband’s large body, his thick legs and broad shoulders. When he’d lain on top of her, she’d felt as if she were stuck in quicksand: no part of her could move; struggle made it worse. It wasn’t an altogether unpleasant feeling. Something about it was a relief. Sometimes she had initiated it, pressing against him in the kitchen or hallway and leading him to their bed, just to feel that weight, to be pressed into the mattress under him. To be obliterated.

Even though he was a big man, there must have been medicine, or enough medicines in combination, strong enough to bring him down. She thought of him as like a racehorse or a wild animal, a moose who had wandered by mistake into a neighborhood, where wildlife officers came and tried to guide it out, following it as long as they could without risking people’s safety. But the moose wouldn’t leave, and it wouldn’t surrender. It couldn’t find its way back to the wild without destroying something, someone’s fence or shed or garden. Finally they had no choice but to shoot it with a tranquilizing gun. Everything would slow then, onlookers watching the effects of medicine powerful enough to bring down the beast in long, exaggerated movements: first its knees buckling, then its haunches falling, until it lay on someone’s front lawn, helpless. She imagined him in his apartment, on the bed they’d bought for him, his haunches still, his head down.

The coffee was good, maybe better than the expensive stuff he’d been bringing her. She carried it to the front window, where she stood and watched the empty street. One of the therapists had told her to acknowledge the emptiness within herself and to learn how to live in that emptiness. She’d nodded as if she bought it, thinking that the guy had no idea about her. Emptiness wouldn’t be a problem. It would be a luxury.

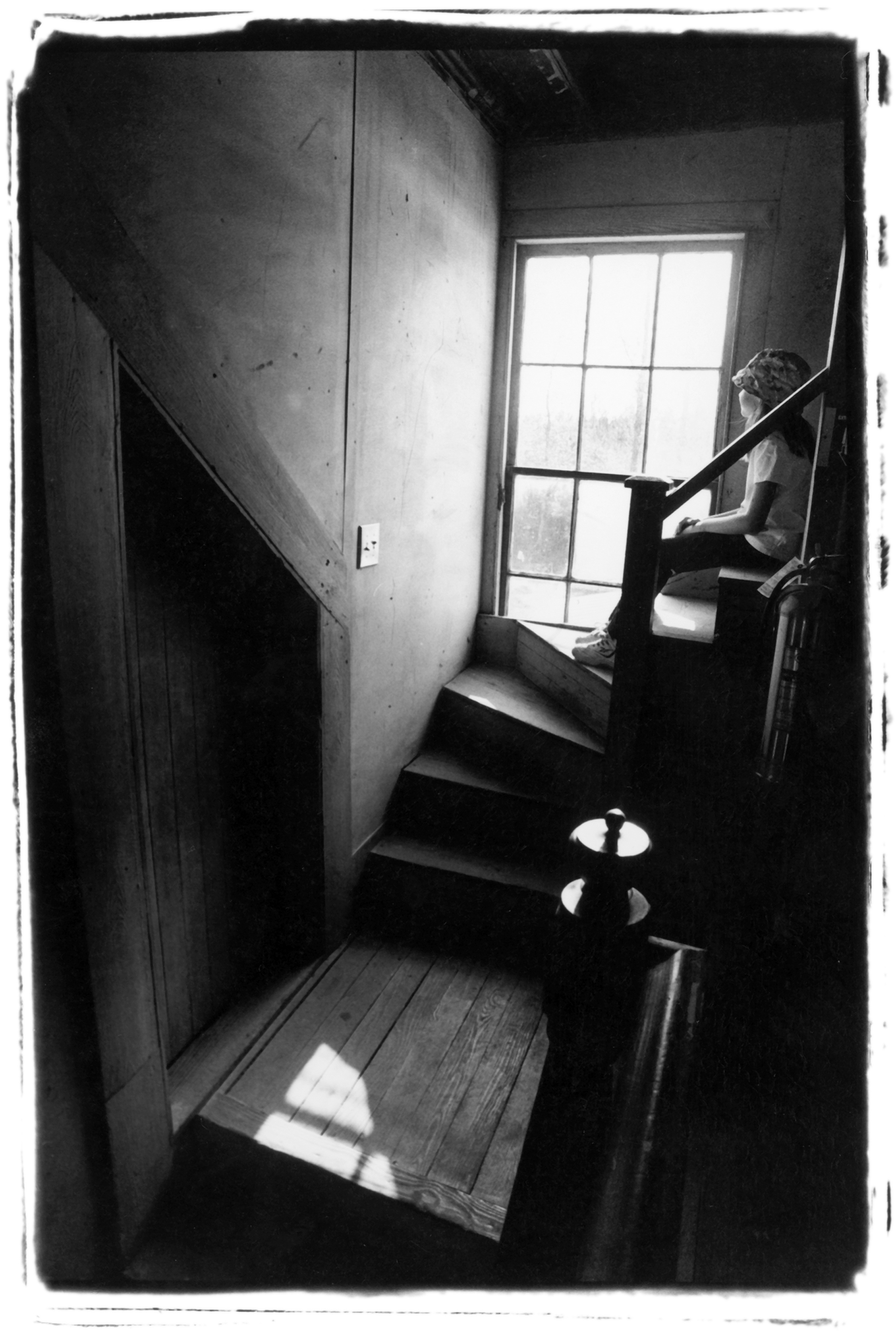

A few minutes passed; then she heard the floor creak above her and turned to see her youngest standing on the stairs, rubbing her eyes. She was seven, small for her age. When she woke in the morning, she looked especially small, underwear gaping open at the leg holes, as though she’d been somehow diminished overnight and needed her mother to hold her, feed her, plump her back up before sending her out into the world of chalkboards and recess and girls with pink ponytail holders. Where’s Daddy? her daughter asked.

I don’t know. He’s late today. Do you want a bagel?

Is he coming?

I can make some scrambled eggs if you want. Come sit with me, she said. She sat down on the sofa.

I’m not hungry, her daughter said, climbing onto her lap. Is Daddy coming? she asked again. Will I see him before school?

She wondered how much medicine it took to kill a wandering moose. She wondered how long it took. What about some cereal? she said.

I want to wait for Daddy, her daughter said.

Her youngest child was the only one who hadn’t been an accident. They’d had a long stretch of something — not good, exactly, but not bad, either — and she’d started thinking about how she missed holding a little body, missed bringing the straining mouth to her breast, missed giving that depth of comfort to another human. She’d pondered it at night, feeling certain that there was one more person who wanted her for a mother. She’d convinced him with that.

When the baby was born, her mother-in-law took the two older children for an entire week, and she and her husband were alone with the baby for hours, the shades drawn against the hottest July in two decades. In the long, quiet moments while their newborn slept, they talked softly and watched one another, remembering something they’d each forgotten.

They indulged the youngest in ways they hadn’t the other two, and the child wrote them notes about what a good mommy and daddy they were and hid them under their pillows before bed. What do we tell her? he asked, after they’d agreed he needed the apartment for both their sakes.

We have to tell each of them the truth, she said. They deserve to know that nothing is their fault.

Of course it isn’t their fault, he said. Why would they think that?

She looked at him for a moment. I don’t want to give them false hope, she said.

What do you mean? he asked. This is just a rough patch.

Is that what it is? she asked, too softly for him to hear.

It was nearly eight o’clock. She thought about how she’d felt after her parents had split up: her father so surprised, her mother so downtrodden. She was nineteen when her mother made the drive to the city to break the news. Her mother was nearly unrecognizable then, the lines around her mouth etched deep, the weight gone from her hips.

Dad and I don’t want this to be a big thing in your life, her mother said. We don’t want you to come home or anything.

OK, she said, trying to give her mother whatever it was she wasn’t asking for. She couldn’t think of anything else to say, wondering how it was that her parents had gotten so far with a relationship that she’d never seen much evidence of, good or bad.

She made it through the rest of her mother’s visit without reacting. But after she’d finally waved goodbye to the back of her mother’s Subaru and the blue hatchback had rounded the corner onto 37th Avenue, she let go of the screen door, went to her room, and slid under her bed, ragged cries emerging from her throat as she tucked her fingers under the wooden slats supporting the box spring.

The child on her lap relaxed against her so the weight felt like her own. Where is Daddy? the child asked.

Daddy isn’t coming today, she said.

Why not? the child asked.

Life would be different without him. She knew it wouldn’t be better, the problems of his presence replaced with the problems of his absence, but some small part of her began sounding a distant drum, issuing forth a call, and for once not of warning. She thought of time — hours of time, twenty-four hours in a row, even — without an e-mail or a phone call or a tap at the door. She thought of sleeping without listening for the creak of the middle stair.

She wondered what would happen to her kids in the years to come, with a father who died from an overdose after a long battle with mental illness. She knew they’d miss him. She’d miss him too. She’d miss his humor, like the time he’d come down the stairs on Christmas morning in her one-piece swimsuit. Look at Daddy! her youngest had shouted, and they’d all turned and laughed, uncertain but amused. And she’d miss the way he knew at first introduction what a person was made of, his bullshit radar unforgivingly precise. That Johnson’s a piece of work, he’d said after they’d met the people who’d moved in next door. Big hat, no cattle.

Maybe she would take her kids on a trip to California. She’d always wanted to take them on a drive down the coast, but car trips had been too fraught with possible triggers that could set him off: car trouble, overbooked hotels, bad weather. In a few months she would take her oldest around the state to look at colleges. They would rent movies on Friday nights and watch them start to finish, nothing to interrupt them.

She would never marry again, never date. Her bed would be her own for the rest of her life. Her sheets would be perfect. She would iron her pillowcase when it came out of the dryer.

I guess I’ll have Luckys, her daughter said, hopping off her lap and heading for the kitchen. Unless all the marshmallows are picked out.

She got up and followed her daughter into the kitchen, pulling the box of Lucky Charms from the top shelf of the pantry. She opened the refrigerator, but there wasn’t any milk there. I’ll have to go to the downstairs fridge, she told her daughter. We’re out of milk up here.

Don’t need milk, her daughter said, shaking the box to unearth marshmallows.

But you do, she said, heading downstairs to the storage room. When she pulled the cord for the light bulb, she tried not to look at the life-size Mr. and Mrs. Claus in the corner and the box of icicle lights they’d bought the previous Christmas, the matching luggage and the old picture frames, the air mattresses and his grandmother’s dishes. She tried not to look, and she tried not to think. Milk. She was simply fetching milk for her daughter’s cereal. She’d deal with the twenty years’ worth of detritus later. After things were more settled.

Coming up the stairs, she heard voices, her daughter saying something about breakfast. She paused on the last stair and listened. She heard the spring in the couch groan, and a familiar smell reached her where she stood, weight on one foot, cold milk carton in her hand.

She thought of her mother, of the apartment she lived in now, of its flowered curtains and narrow hall. She thought of the letters her mother sent, two each month, with news of the fun she’d had in Palm Springs over the weekend, or of the new car she was saving for.

And she thought of her father and the woman he was seeing, whose husband had died of a heart attack while playing racquetball. She thought about how they had joined the country club and ate dinner there on Fridays.

She thought of her husband, how he persisted in the face of his illness. She remembered precisely the day she’d met him. He’d been a boy with a quick smile and turned-in front teeth. She remembered how badly she had wanted him. She thought of how horrible it all was. And how precious.

She thought of the milk in her hand, how she insisted her daughter have milk with the junky cereal, as if the wholesomeness might offset the lack of nutrition in the tall red box of sugar. She looked at the milk carton, at the place where the cardboard lay against her hand, and she saw her wedding ring and thought about how cold it felt, how the band absorbed the coldness. She wondered how she’d incorporate a carton of milk into the juggling act, with its long shape and sloshing insides. She sat on the stair, the chill of the carton nestled between her lap and her stomach.

I told her we should wait, her daughter was saying. I knew you’d want to have your cereal with me.

Where is she? he asked. Where’s Mom?

She’s getting milk, silly, said her daughter.

Well, she’d better get up here, he said. I brought coffee.