Anyone who has spent a few hours on the Internet understands how reading a single paragraph can lead to a multimedia journey so far-reaching you forget what you originally went online to look up. Nicholas Carr — author of last July’s Atlantic cover story, “Is Google Making Us Stupid?” — believes the distracted nature of Web surfing is reducing our capacity for deep contemplation and reflection. He began developing his theory when he realized that, after years of online information gathering, he had trouble reading a book or a magazine. As he puts it, “I’ve had an uncomfortable sense that someone, or something, has been tinkering with my brain, remapping the neural circuitry, reprogramming the memory. . . . I’m not thinking the way I used to think.”

Growing up in a small town in central Connecticut in the seventies, Carr couldn’t have imagined he’d someday make a career of critiquing computer technology. He read a great deal as a boy and entered Dartmouth College with hopes of becoming a writer. He graduated in 1981 with a degree in English literature and spent a year working as an editor and playing in a punk-rock band before he entered a graduate program in English literature at Harvard University. The theoretical focus of his courses failed to captivate him, however, and Carr soon realized that he didn’t want to become a professor. He got his master’s degree and left.

Carr and his new wife had a baby on the way, so he took an editorial position at a management-consulting firm. He ended up staying twelve years and getting an education in business, economics, and the blossoming field of information technology, or it. In 1997 he became senior editor of the Harvard Business Review. It was the height of the dot-com boom, and Carr spent nearly six years editing articles about business strategy and it. Then in 2003 he wrote an article for the Review titled “IT Doesn’t Matter,” arguing that as computers have become almost universal, they no longer provide a competitive advantage to companies. The piece aroused much interest — and contempt; Microsoft ceo Steve Ballmer called it “hogwash.” Harvard Business School Press offered Carr a book contract, and Does IT Matter? was published in 2004. That success led to a second book, The Big Switch (W.W. Norton & Co.), about “cloud computing” — providing computing software over the Internet, like electric power sent out over a grid. While writing The Big Switch, Carr became interested in the social and cultural implications of the Internet, which led to his Atlantic cover story and the book he’s currently working on, tentatively titled The Shallows: Mind, Memory, and Media in an Age of Instant Information.

As for all those years studying literature, forty-nine-year-old Carr has no regrets. In fact, he believes learning to deconstruct poems and stories trained him to think analytically and led him to where he is today. Carr’s methodical mind — the “Google effect” notwithstanding — has given him an impressive ability to dissect the ever-expanding cyberworld. He blogs at www.roughtype.com and recently moved from New England to the Colorado Rockies to spend more time outdoors, hiking, fly-fishing, and skiing — and deepening his ability to be contemplative.

NICHOLAS CARR

Cooper: You’ve quoted Richard Foreman, author of the play The Gods Are Pounding My Head, who says we are turning into “pancake people.”

Carr: We used to have an intellectual ideal that we could contain within ourselves the whole of civilization. It was very much an ideal — none of us actually fulfilled it — but there was this sense that, through wide reading and study, you could have a depth of knowledge and could make unique intellectual connections among the pieces of information stored within your memory. Foreman suggests that we might be replacing that model — for both intelligence and culture — with a much more superficial relationship to information in which the connections are made outside of our own minds through search engines and hyperlinks. We’ll become “pancake people,” with wide access to information but no intellectual depth, because there’s little need to contain information within our heads when it’s so easy to find with a mouse click or two.

Cooper: In your Atlantic article “Is Google Making Us Stupid?” you suggest that using the Internet has actually lessened your ability to concentrate while reading. What led you to this conclusion?

Carr: I was having trouble sitting down and immersing myself in a book, something that used to be totally natural to me. When I read, my mind wanted to behave the way it behaves when I’m online: jumping from one piece of information to another, clicking on links, checking e-mail, and generally being distracted. I had a growing feeling that the Internet was programming me to do these things and pushing on me a certain mode of thinking: on the one hand, distracted; on the other hand, efficient and able to move quickly from one piece of information to another. In the article, I focused on Google because it’s the dominant presence on the Net — at least, when it comes to gathering information. It provides a window into how the Internet is imposing its own intellectual ethic on its users at both a technological and an economic level.

Because Google makes money based on how many ads we see and how often we click on them and jump to another page, it has a strong interest in getting us to move around the Web as quickly as possible. In some ways the nightmare scenario for a company like Google is that we slow down and spend a lot of time with one source of information.

Even aside from Internet business strategies, this tendency toward distraction is built into the Net through the use of hyperlinks and search engines, and I believe it’s beginning to influence not simply how we gather information but also how we think.

Cooper: In the September 2008 issue of Wired David Wolman answers your question “Is Google making us stupid?” with “No, but it makes a handy scapegoat for an inability to cope with information overload.” He goes on to say, “The explosion of knowledge represented by the Internet and abetted by all sorts of digital technologies makes us more productive and gives us the opportunity to become smarter, not dumber.” What’s your response?

Carr: There have been two general criticisms of my article. One is that the phenomenon that I write about — the loss of the ability to concentrate and be contemplative — simply isn’t happening. The other is that it’s happening, but what we gain is much greater than what we lose. I think the Wired piece is more in the latter camp: this wealth of information is so beneficial, the argument goes, that it doesn’t matter if our brains change.

I guess it comes down to what you value about human intelligence and, by extension, human culture. Do you believe that intelligence is a matter of tapping into huge amounts of information as fast as possible — being “more productive,” as the Wired writer says — or do you think intelligence means stepping back from that information, thinking about it, and drawing your own conclusions in a calm, thoughtful way? My own feeling is that I’d rather have less information and more thoughtfulness. I certainly want information, but information isn’t an end unto itself. Human intelligence is the ability to make sense of that information.

Cooper: Is there any real evidence that the Internet is “rewiring” our brains?

Carr: There’s certainly a lot of evidence that the brain readily adapts to experience — that our neural circuits are “plastic,” as scientists say. And we’re starting to see direct evidence that Internet use alters brain function. There was a fascinating study done in 2008 by Gary Small, who heads the UCLA Memory and Aging Research Center and recently published a book called iBrain. He and two of his colleagues scanned the brains of two dozen people as they searched the Internet: half the subjects lacked online experience, and the other half were experienced Web users. The researchers found very different patterns of brain activity between the two groups. The subjects with little experience on the Internet showed activity in the language, memory, and visual centers of the brain, which is typical of people who are reading. The experienced Web surfers, on the other hand, had more activity in the decision-making areas at the front of the brain. Interestingly, after five consecutive days of Web surfing, the brain activity of the “inexperienced” group began to match the activity of the experienced Web users. That indicates that the brain adapts very quickly to Net use, just as it does to other repeated stimuli.

Now, there’s good news and bad news here. The good news is that, if you’re older, using the Net may help keep you mentally sharp. It “exercises” the brain in the way that, as Dr. Small observed, solving crossword puzzles does. On the other hand, neurology experiments demonstrate that decision-making consumes a lot of your mental resources, leaving less available for other modes of thinking. That may be why it’s so hard to read deeply when we’re online — our brains literally become overloaded. Imagine trying to read a book while simultaneously working on a crossword puzzle. That’s the intellectual environment of the Web.

Cooper: Do the different areas of activity that show up on the scan necessarily mean the brain is being “rewired”?

Carr: If everybody in the study had shown the same pattern of brain activity from the start, that would have told us that this is just the way your brain works when you surf the Web. But because the patterns differed between experienced and inexperienced users, and because they changed for the inexperienced group as they used the Web more, it means the brain is adapting. People used to think that after childhood your brain was basically hard-wired, but we know today that even the adult brain is very plastic. Throughout our lives our brains adapt to the way we gather and process information. Performing an action over and over changes the brain’s circuitry. The new firing patterns of neurons become more stable and push aside older patterns. If you give up performing an action, then neural circuits formerly dedicated to it get weaker and are eventually used for other activities.

Cooper: So this rewiring isn’t something unique to Google or the Internet.

Carr: That’s right. Anything we do on a regular basis rewires the brain. There’s a saying among neuroscientists that “neurons that fire together, wire together.” When you practice a certain skill, the circuits get stronger, and the area of your brain dedicated to performing the skill gets larger.

What that means is that, as the Internet becomes our universal medium for gathering information, we’re training our brains to take in information in the way the Internet supplies it — that is, with an emphasis on speed and with continual distractions. We’ve seen this with previous intellectual technologies like the alphabet, the clock, and the printing press: new modes of intelligence come into being that stress different aspects of our brain’s functioning. Some people would argue that, with the current change, we’re gaining a great deal, because we have access to all this information. And for most of us the obvious benefits of being online overwhelm any fears and concerns. This has been particularly true with young people who’ve grown up with this new technology. Because it’s become so natural, they don’t pay attention to what they might be losing. They might not even be aware of it. You don’t worry about losing something you never knew you had in the first place.

Cooper: What do you personally do to address the negative effects of the Internet on your brain?

Carr: I’m trying to put some limits on my Internet and e-mail use, but that’s not always possible. There are broad social and economic changes underway that reward Internet use. If you cherish the ability to concentrate deeply and be reflective, you need to set aside time to read and think every day, so that those circuits in your brain don’t get erased.

Cooper: You’ve been called “the technology world’s public enemy No. 1.” How accurate is this characterization?

Carr: [Laughter.] That’s a phrase that was used in Newsweek. Back in 2003, while I was working for the Harvard Business Review, I wrote an article called “IT Doesn’t Matter,” which basically argued that computers aren’t providing businesses a competitive advantage anymore, because they’re so commonplace. That ruffled a lot of feathers in the computer industry. Since then I’ve broadened my critique and examined my own personal relationship to computers, which has been one of mixed feelings. On the one hand, I’ve always been more of a technophile than a technophobe. I got my first personal computer, a Mac Plus, in the eighties and have been an enthusiastic adopter of new computer technologies since then. I certainly appreciate the way computers and the Internet have made my work easier. Yet over time I also feel more and more resistant to their charms and more suspicious of the negative effects they might be having on all of us.

Cooper: Do you think computers have harmed our relationship with nature?

Carr: I certainly think they’ve gotten in the way of our relationship to nature. As we increasingly connect with the world through computer screens, we’re removing ourselves from direct sensory contact with nature. In other words, we’re learning to substitute symbols of reality for reality itself. I think that’s particularly true for children who’ve grown up surrounded by screens from a young age. You could argue that this isn’t necessarily something new, that it’s just a continuation of what we saw with other electronic media like radio or TV. But I do think it’s an amplification of those trends.

Cooper: What about the interactivity of the Internet? Isn’t it a step above the passivity that television engenders?

Carr: The interactivity of the Net brings a lot of benefits, which is one of the main reasons we spend so much time online. It lets us communicate with one another more efficiently, and it gives us a powerful new means of sharing our opinions, pursuing our interests and hobbies with others, and disseminating our creative works through, for instance, blogs, social networks, YouTube, and photo-publishing sites. Those benefits are real and shouldn’t be denigrated. But I’m wary of drawing sharp distinctions between “active” and “passive” media. Are we really “passive” when we’re immersed in a great novel or a great movie or listening to a great piece of music? I don’t think so. I think we’re deeply engaged, and our intellect is extremely active. When we view or read or listen to something meaningful, when we devote our full attention to it, we broaden and deepen our minds. The danger with interactive media is that they draw us away from quieter and lonelier pursuits. Interactivity is compelling because its rewards are so easy and immediate, but they’re often also superficial.

As we increasingly connect with the world through computer screens, we’re removing ourselves from direct sensory contact with nature. In other words, we’re learning to substitute symbols of reality for reality itself.

Cooper: How has public perception of computers changed over the years?

Carr: The public has always been of two minds when it comes to computers. Back when companies and governments were installing the first mainframes, there was a fear that we might lose our humanity and be turned into strings of numbers processed by machines. So in the sixties, students not only burned their draft cards; they also folded, spindled, and mutilated ibm computer cards to protest the “institutional” machines that they feared might enslave them in some way.

At the same time, some in the counterculture became enthusiastic about computers as personal tools that would not control us but liberate us by giving us more power to create and communicate with others. In other words, computers could be a weapon against corporate and governmental control. That idea was central to the early personal-computing movement, and it lay behind the formation of, say, Apple Computer.

Since the sixties, the fear that the computer might threaten our humanity has become submerged, and the view of computers as useful tools has grown more dominant. I don’t think, though, that people view their pcs as countercultural tools anymore. They’re mainstream tools, and they’re used as much to connect with corporations and institutions as for any other purpose. They’ve become an integral part of consumer society rather than an alternative to it. I worry that, as we’ve become entranced by the bounties that the pc and the Net deliver, we’ve blinded ourselves to their role as controlling technologies.

Cooper: What do you mean by a “controlling technology”?

Carr: Computers were originally developed for military applications — for figuring out the trajectories of bombs and missiles — and then they were adapted for business use. Their fundamental purpose was to automate and control processes that had once been done by hand. Soon the steps a worker took in his or her job were largely determined by the software of the computer system. Computer networks also provide a great way for companies to monitor employees and customers. Because computers become more useful as you put more information into them, the idea of privacy is antithetical to the ongoing expansion of their use.

Cooper: Speaking of privacy, can you talk about Tom Owad’s experiment?

Carr: Tom Owad writes a blog about Apple computers, and a while back he decided to do an experiment using just his home computer and information that’s available through Amazon.com. Amazon allows buyers to set up “wish lists” of items in which they’re interested. Owad realized that these lists provide a window into an individual’s views, because what you read or buy says a lot about you. He also realized that you can download the data in the lists fairly easily and analyze it to discover patterns.

So he downloaded many thousands of these personal wish lists, which are often attached to demographic information like addresses, birthdays, and anniversaries — enough for him to do an online people search and attach specific wish lists to individuals. He was able, for example, to create a Google map of people interested in George Orwell’s novel 1984. The experiment revealed that we expose ourselves online in many ways without being conscious of it. And it’s quite easy, not only for an individual like Owad but for a government or corporation, to mine this information and get insight into who we are and what we think.

Cooper: Let’s say people were more conscious of this. Do you think they’d resist?

Carr: If you ask people whether they’re concerned about the ability of the government or corporations to gather information about them online, they’ll say yes. But if you look at how they behave online, they don’t display much fear of exposing themselves. What that says about people — and it’s true for most of us — is that we will readily forgo our privacy in exchange for convenient and useful services, particularly if they’re free. That’s a trade-off you make all the time on the Internet. Even if people were more conscious of how this information might be exploited, I doubt most would change their behavior.

Cooper: If you do shop online, what’s so bad about being targeted by advertisers who know a lot about you?

Carr: One of the benefits of disclosing a lot of information about yourself to corporations is that they can do a better job of tailoring products and advertisements to your particular needs. The question is, when does customized service cross the line into manipulation? The Internet is a system of computers, and from the start computers have been used to direct people toward a specific goal established by the designer of the computer software. With the information available online, businesses can decipher triggers of our behavior.

Cooper: But isn’t the Internet freeing us by helping to connect people from different parts of the world?

Carr: Yes and no. In many cases it’s allowing information to flow more freely across borders, and that can help build understanding and empathy. But we’ve also heard a lot of rhetoric about how the Internet is going to erase old geopolitical boundaries and undermine the power of governments and so forth, and that’s largely a fantasy. As the Web has evolved, we’ve seen that our online activities are in fact subject to real-world laws and boundaries. Yahoo! was charged in France with allowing the sale of Nazi memorabilia, which is illegal in that country. Yahoo!’s initial reaction was to argue that French laws don’t apply to the Net, but it soon retreated with its corporate tail between its legs because, as is true of any Internet company, it has to obey the laws of nations in which it operates.

Cooper: Is it bad that Yahoo! had to stop the sale of Nazi memorabilia?

Carr: No, I don’t think it’s bad. I’m in favor of maintaining local differences not only in laws but also in cultures. If the Internet were above the reach of local laws, there’d be a danger of even greater cultural homogeneity than we already have. But the point of the story is that the Net is not going to successfully challenge governmental sovereignty, as some of the more utopian thinkers suggest.

Cooper: Doesn’t the Internet provide a means of communication to people whose freedom of expression is limited by oppressive regimes? Iranians are some of the most active bloggers in the world.

Carr: The Internet, paradoxically, empowers both the individual and the state. On the one hand, it allows people who had no way to express themselves before, whether for political or economic reasons, an outlet to do so. The Net also makes it much easier to find out what people in other countries are thinking. On the other hand, it gives governments a better view into their citizens’ activities. There’s a danger that some people might mistake the apparent anonymity of the Net for true anonymity. It’s pretty easy for a government to get into the records of Internet providers and track who’s saying what. An anonymous person in China sent an e-mail containing what the Chinese government considered sensitive information, and the government demanded that Yahoo! disclose the identity of that person. Yahoo! agreed, and the man was put in jail. This is another indication that governmental control does not go away when people begin using the Internet. In fact, the Web gives governments a new tool for monitoring speech.

In most places the Net is still, on balance, more of a liberating force than a controlling one, but there’s no guarantee that this will continue. A utopian view of the Net needs to be tempered by the realization that it provides a remarkable infrastructure for totalitarianism. We can only hope it never gets used that way.

Cooper: But you don’t dispute that the Net is helping to democratize media?

Carr: The Internet has given many people the opportunity to express their views or distribute their creative work. It brings down the economic and technological barriers that once surrounded the media. Here too, though, the rhetoric often exceeds the reality. Though in theory you can reach a global audience through the Internet, the reality is that the vast majority of blogs, for example, are read by very small audiences. Writing one is not all that different from publishing your own photocopied zine in the eighties or being a ham-radio operator in the fifties.

There’s also an exploitative side to the Internet’s democratization of the media. When people post videos on YouTube or photos on Flickr, they’re essentially providing free content to a profit-making corporation. I’ve compared this to a sharecropping model, where a company like Yahoo! or Google gives you your own plot of virtual turf and some tools to work it, but they’re the only ones who make any money from your work.

As more and more companies are able to harvest the fruits of free labor, it hurts the professionals who are trying to make a living and who are often very good at what they do. That’s not to take anything away from the amateurs, but if you look at how the rise of blogs has coincided with layoffs of reporters at newspapers, for example, it should give some cause for concern.

The human mind has been shaped in profound ways by the invention of the alphabet, the map, the book, and many other media technologies — and we did not get to control the shaping process. We control some aspects of our technologies, but our technologies control some aspects of us.

Cooper: You’ve said that the “unbundling of content” online is killing investigative journalism. What is “unbundling”?

Carr: The Internet allows media that used to be bundled together — such as articles in a newspaper or songs on a cd — to be unbundled, so that people can access the pieces individually. I no longer have to go out and buy a newspaper; I can launch my browser and find individual stories. I don’t have to buy a whole album; I can download individual songs from iTunes. An economist would say that’s good, because it means consumers have to purchase only those particular items that interest them, and they can ignore everything else. That’s true, but we may lose something along the way. The bundling of different content allowed newspapers, for instance, to take the money from classified ads and subscribers who read only the sports page and to invest it in stories that wouldn’t have been profitable on their own — and this includes most investigative journalism. On the Internet the classified advertising is unbundled: some of it goes to Craigslist, some to Autotrader.com, and so on. When people can get sports scores on their cellphones, they buy fewer papers. As the parts become separated, there’s no longer enough revenue to subsidize the less-profitable parts of the news business, and they are the first to be trimmed. They may also be some of the most valuable parts for society.

Cooper: With the declining ad revenues and readership at most major newspapers, do you think journalism will continue to be a paid profession?

Carr: There will always be opportunities for people to make a living as journalists, but the ranks of journalists will decrease. One of the great ironies of the Internet is that even though it provides us with easy access to an incredible amount of information, we get fewer professional voices and fewer reliable sources of information.

Cooper: What about the political blogs? We get lots of information there.

Carr: That’s true. In many ways the blogosphere is like the Op-Ed page on steroids. It gives people access to many different views, not all of which were easily accessible before. But we haven’t seen blogs, or any other type of amateur or unpaid journalism, replicate the news media’s more costly elements, like overseas reporting. The reason we see so many political and opinion blogs is that there’s no overhead on giving your opinions.

Cooper: Blogs tend to be either very liberal or very conservative. Do you think that’s because of human nature, or is it a polarizing effect of the Net itself?

Carr: I think it’s both. Obviously if you’re going to devote your time to writing a political blog, you probably have strong views on one side or the other of the political spectrum. And the more-ideological blogs tend to get more attention. Studies also demonstrate there’s little interaction between the two sides. Liberal blogs tend to link to other liberal blogs; conservative blogs link to other conservative blogs. As this effect continues, people may end up becoming more polarized rather than thinking more broadly.

And this is not only true on the Net; we’ve seen this polarization in talk radio and the cable news networks too. We seem to be moving toward an ever more Balkanized political landscape, which makes it harder for government to operate. You have to wonder how well our form of government, which is built on compromise, will adapt to this.

Cooper: You’ve also said that computing is concentrating income at the top of the ladder.

Carr: Businesses buy computers to replace workers, because machines tend to be less expensive. Jobs that used to be done by hand, such as typesetting, accounting, and filing, are now done by computer. Replacing workers with technology is nothing new. It’s been going on since the Industrial Revolution. Ideally, when you replace labor with machines, productivity goes up, and other jobs are created that replace the ones made obsolete by machines. Early industrial technologies put craftsmen out of business, but they created lots of factory jobs. And as companies became bigger and more complex, there was an explosion in white-collar jobs, which boosted living standards.

What seems to be different this time is that although computer systems allow the automation of many additional jobs, including white-collar work, we haven’t seen broad new classes of good-paying jobs coming out of the computer revolution. As you replace labor with capital, the owners of capital — along with the top executives who manage the business — are able to skim more profits from corporate earnings for themselves, and more and more money goes to a smaller set of people. That’s a trend we’ve seen here in the U.S. for the last couple of decades. Most economists believe information technology is one of the forces behind this concentration of wealth.

Cooper: If computers are cheap and the Internet is becoming the world’s computer, doesn’t that level the playing field in business?

Carr: It should help level the it playing field, giving smaller companies access to powerful computing resources that in the past have been reserved for larger companies. As computing power and software programs turn into utilities, delivered for a monthly fee over the Net from huge data centers, it frees businesses from having to devote capital to the machinery. That’s good for small businesses, which tend not to have a lot of capital to invest.

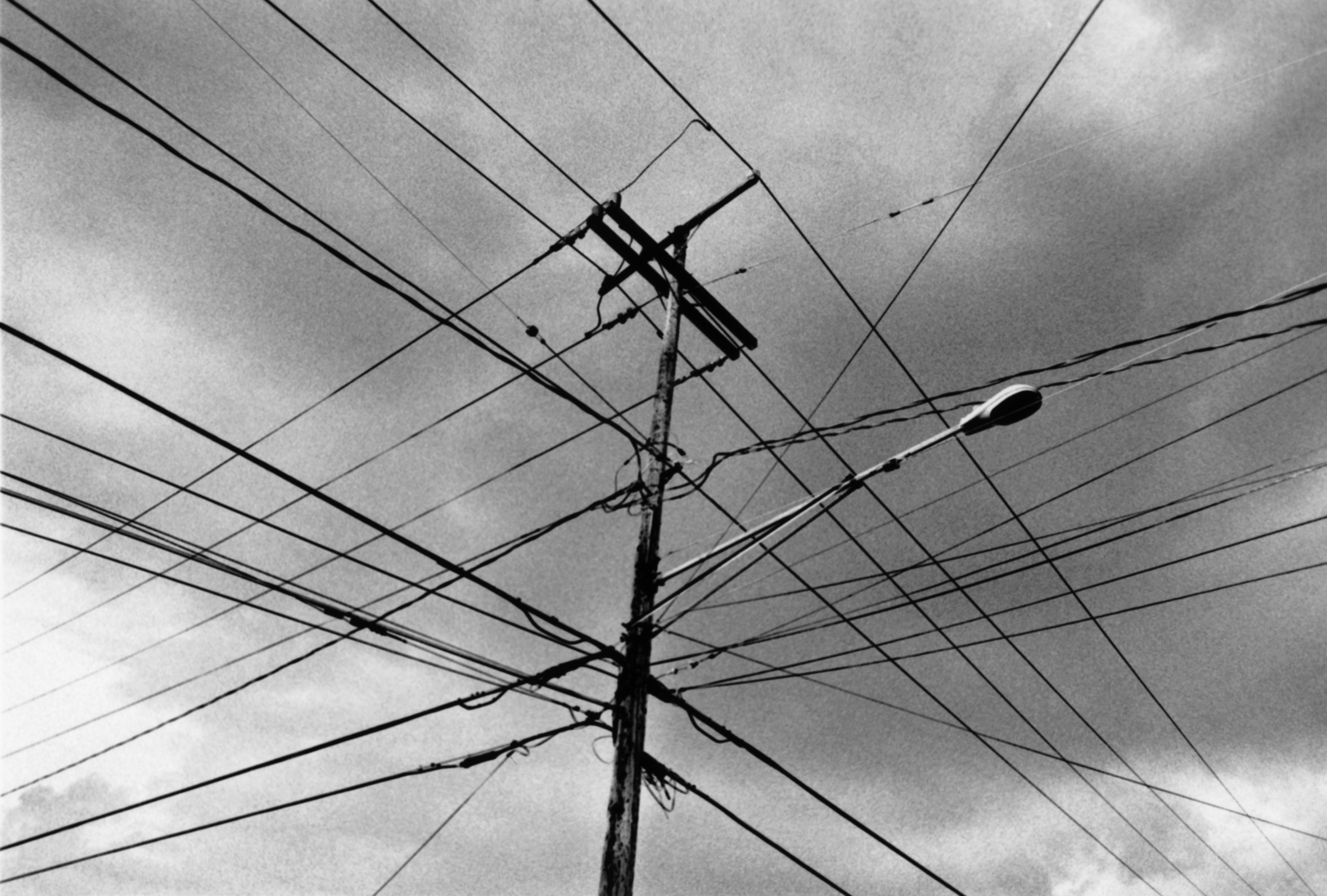

The Internet is becoming, in essence, a shared computer that all of us use. Ten years ago your computer was a self-contained device, and all of its functions were running off your hard drive. Today you can launch your Web browser and access all sorts of software and data online. It’s called “cloud computing”: obtaining computing capabilities over the Internet rather than from your own personal computer or corporate server. Computer technology, like electrical power a hundred years ago, is increasingly being supplied by central “power plants.” I think we can expect the same result we saw when electrical current went from being supplied locally by private generators to being a utility served up over the electric grid: efficiency will increase, and the cost of computing will probably continue to go down dramatically.

Cooper: Yet there’s a trend in some places to move back to home supply, where people have solar panels on their house and aren’t threatened by the instability of the big grid.

Carr: Yes, there’s a trade-off. When you rely on the big grid, you tend to get the power cheaper, but you become more dependent on that central system and the companies that run it. The trade-off with cloud computing is that, on the one hand, you get sophisticated computer programs and huge pools of data for cheap or for free; but, on the other hand, more and more of your personal information is going into central databases operated by profit-making companies. These companies are getting very good at mining that data. We don’t know what the endpoint of that will be. Will companies have so much of our information that they’ll be able to manipulate us in ways we’ll unable to perceive? We leave so many traces of our behavior and our desires through what we do online, whether it’s searches or purchases or looking at different media. If a company can aggregate and analyze all that data, there’s no telling what it might be able to do with it.

Cooper: It sounds like an advertiser’s dream come true.

Carr: In many ways it is. There’s a famous quote from retail tycoon John Wanamaker at the start of the twentieth century: “I know that half my advertising doesn’t work. The problem is I don’t know which half.” The Internet solves that problem for companies.

Cooper: Richard McManus, founder and editor of ReadWriteWeb.com, conducted a study and found that more Internet traffic is going to a smaller number of sites. What are the implications of this?

Carr: This is another of the Internet’s many paradoxes: although the number of sites continues to grow, a small number of sites dominate an ever-greater share of the traffic. It was once believed that the Web was essentially centrifugal: that it pushed people away from big, central sources of information to millions of small, independent sources scattered throughout the network. But it turns out that centripetal forces — forces that draw us back to the big power centers — are also strong on the Web. Big sites have big advantages, and they seem to get stronger over time. The Net’s Wild West days are coming to an end. The trend now is more toward the consolidation of traffic and power than toward their diffusion.

Cooper: Some have described the online, user-generated encyclopedia Wikipedia as an example of a “collective mind.” What’s your take on Wikipedia?

Carr: I’m not sure what a collective mind is, but I’m pretty sure Wikipedia isn’t one. I think Wikipedia is the product of a large group of individuals engaged in a collaborative exercise in paraphrasing and editing. It couldn’t have happened without the Internet, and, judging by its popularity, it’s been incredibly successful. It’s also a useful service if you’re looking to get a quick gloss on a subject. I see no evidence that it’s made humankind smarter or more thoughtful, though. And Wikipedia provides a great example of the ongoing concentration of traffic on the Web. Wikipedia has become a giant black hole that sucks traffic away from other, smaller sites — sites that often have richer, more-nuanced information than Wikipedia supplies.

Cooper: Wikipedia cofounder Larry Sanger says you’re blaming the Internet and programmers for your own unwillingness to think long and hard. What’s your response to that?

Carr: That’s a variation on the old “guns don’t kill people; people kill people” theme. It implies that technologies influence us only when we allow them to influence us, and that we control the nature of that influence. It’s a comforting idea, because it puts us in the driver’s seat, but it’s nonsense, as a quick glance at history will tell you. The human mind has been shaped in profound ways by the invention of the alphabet, the map, the book, and many other media technologies — and we did not get to control the shaping process. We control some aspects of our technologies, but our technologies control some aspects of us. There’s a memorable sentence in Marshall McLuhan’s book Understanding Media: “Our conventional response to all media, namely that it is how they are used that counts, is the numb stance of the technological idiot.”

A definition of intelligence that discredits the individual mind in favor of some automated collective mind will feed powerful systems: governments, corporations, and other large institutions. And it will emphasize efficiency of thought over depth of thought.

Cooper: In the “iGod” chapter of your book The Big Switch you describe Google’s desire to “have the entire world’s knowledge connected directly to your mind.” Google cofounder Sergey Brin even hypothesizes about “a little version of Google that you just plug into your brain.”

Carr: The Googlers are nothing if not ambitious. All information technologies, I believe, have an intellectual ethic — in other words, a set of assumptions about how we should use our brains. And Google’s ethic reflects its origins in computer science. It wants to make us fast, efficient collectors of information, in many ways mimicking computers. If you look at the pronouncements of Google’s founders or its ceo, you see that their goal is for the Google search engine to become a form of artificial intelligence. They want it to be something that extends the capacity of your mind, or even provides you with a better mind than your old-fashioned flesh-and-blood one. They seem to believe that ultimately the Internet will provide the basis for the next generation of human intelligence — you could say posthuman intelligence.

Cooper: What’s wrong with that?

Carr: Well, for one thing, computers have yet to replicate any aspect of human intelligence in a meaningful way. So the glorification of artificial intelligence, or machine intelligence, reflects a narrow view of human intellect and human potential — one that is essentially mathematical and industrial and doesn’t give much credit to the great triumphs of culture: works of art, literature, music, architecture. My fear is that a definition of intelligence that discredits the individual mind in favor of some automated collective mind will feed powerful systems: governments, corporations, and other large institutions. And it will emphasize efficiency of thought over depth of thought. I fear we’re going to lose, as I’ve said, the kind of contemplative, reflective intelligence that is most valuable, most human.

Cooper: So what are you going to do when Google-chip implants become as necessary as credit cards?

Carr: Probably get one. [Laughter.] My guess is I won’t be around by the time that happens, but I think it’s probably what people will end up doing, if it becomes possible, because we will likely be rewarded handsomely for it. Having the chip will become necessary for success in your professional and social life, and hence hard to resist. If you’ll walk around with a Bluetooth headset hanging from your ear, you’ll probably walk around with a Google chip in your brain.

Cooper: I guess it’s no surprise that this is not even on the political radar.

Carr: Politicians are afraid of being seen as elitists or intellectuals. And let’s face it: how we define intelligence is a pretty intellectual concept. So I don’t have any expectation that it will enter into the political discussion. Even during the presidential campaign, we could see that our bias as a society is toward an ever-greater dependence on computers. John McCain was ridiculed for his lack of facility with the Internet. So our tendency is to venerate technology and progress without ever really questioning it.

Cooper: Some have suggested creating a department of technology in the government.

Carr: I think if we set up such a department, its purpose would only be to promote technology from an economic standpoint. If you look at education, for instance, technology has become a huge component of the school budgets, even down to the elementary grades. The assumption is that access to computers and the Internet provides a big educational benefit for young children, even though there is no solid evidence for this.

As we are inundated with information, there’s certainly a need to train children how to make sense of it all — to make them savvy about the Internet and teach them to identify what can be trusted and what should arouse suspicion. But making people smarter about navigating the Net is a separate issue from whether computers help us learn or think.

Cooper: There’s been a lot of discussion recently about how much the new president needs to understand the inner workings of the Internet.

Carr: The Internet is becoming the world’s major economic infrastructure, and I don’t think politicians have really grasped the challenges of having computer servers that are outside our country running important parts of our economy. Over the next few years, probably during Barack Obama’s first term, it’s certainly going to become a political issue, because a country’s competitiveness and wealth are going to be tied up in this network, and there’s going to be geopolitical tension over who controls it and how it works. Not only the president but also lawmakers, regulators, and even judges will need to become educated about the Internet and its implications, whether they like it or not.