I arrived in Paris early in the morning, checked into a family-run hotel in Montmartre, and immediately wanted to fall in love.

It began with the scarves. On the Métro that first morning I found myself staring across the car at a woman’s scarf: blue silk with a white pattern, tied in a loop of almost mystical elegance. It suddenly seemed as if all the women of Paris were wearing scarves: tied in a crisscross, thrown loosely around the neck, draped across the chest with a knot at one shoulder, all with an unmistakable style and knowingness. This same knowingness was apparent in their bracelets, too, if you can imagine such a thing. And their legs — their legs above all: some bare, the rest barely stockinged; brazen, elegant, smooth. In India, where I’d just come from, the women had been all breasts and hips, pulled tight within the thin folds of their saris. Paris was all legs. Legs and scarves. Or maybe it wasn’t; maybe I was just a bit hard up. After all, I’d been traveling a long time and hadn’t had sex in months.

We hear so much about the romance of travel, but nothing beats romance while traveling. I’d found it on a number of occassions, sometimes in the strangest of circumstances: while monitoring election results in El Salvador or staying in a dismal youth hostel during a rain-besotted Irish winter. If I could find love there, why not in Paris in the spring?

I thought of Fiona, the lovely brunette I’d met two months earlier at the Doi Suthep monastery. In spite of the monastery’s precepts — which forbade killing any kind of living creature, drinking any kind of alcoholic beverage, and engaging in any kind of sexual activity — a handful of karmically laden pheromones had passed between us. I’d sent her an e-mail after I’d left, asking if she would like to meet me in Bangkok to break some precepts together. Whether she thought I meant have a beer, get a room, or kill a few mosquitoes, her reply was an enthusiastic yes. Our itineraries never crossed, however, and by the time she’d arrived in Bangkok, I was already in Malaysia.

Sitting in an Internet cafe in Paris, I figured that Fiona should be back home in England by now. I e-mailed her: “It’s spring. It’s Paris. It’s glorious. Care to pop down from London?”

The next day I checked for a reply: nothing. Nor the day after that, nor the day after that. “The bitch,” I whispered under my breath. This being Paris, I tried to say it the way Jean-Paul Belmondo had said it to Jean Seberg as he lay dying, shot down in the street at the end of Breathless.

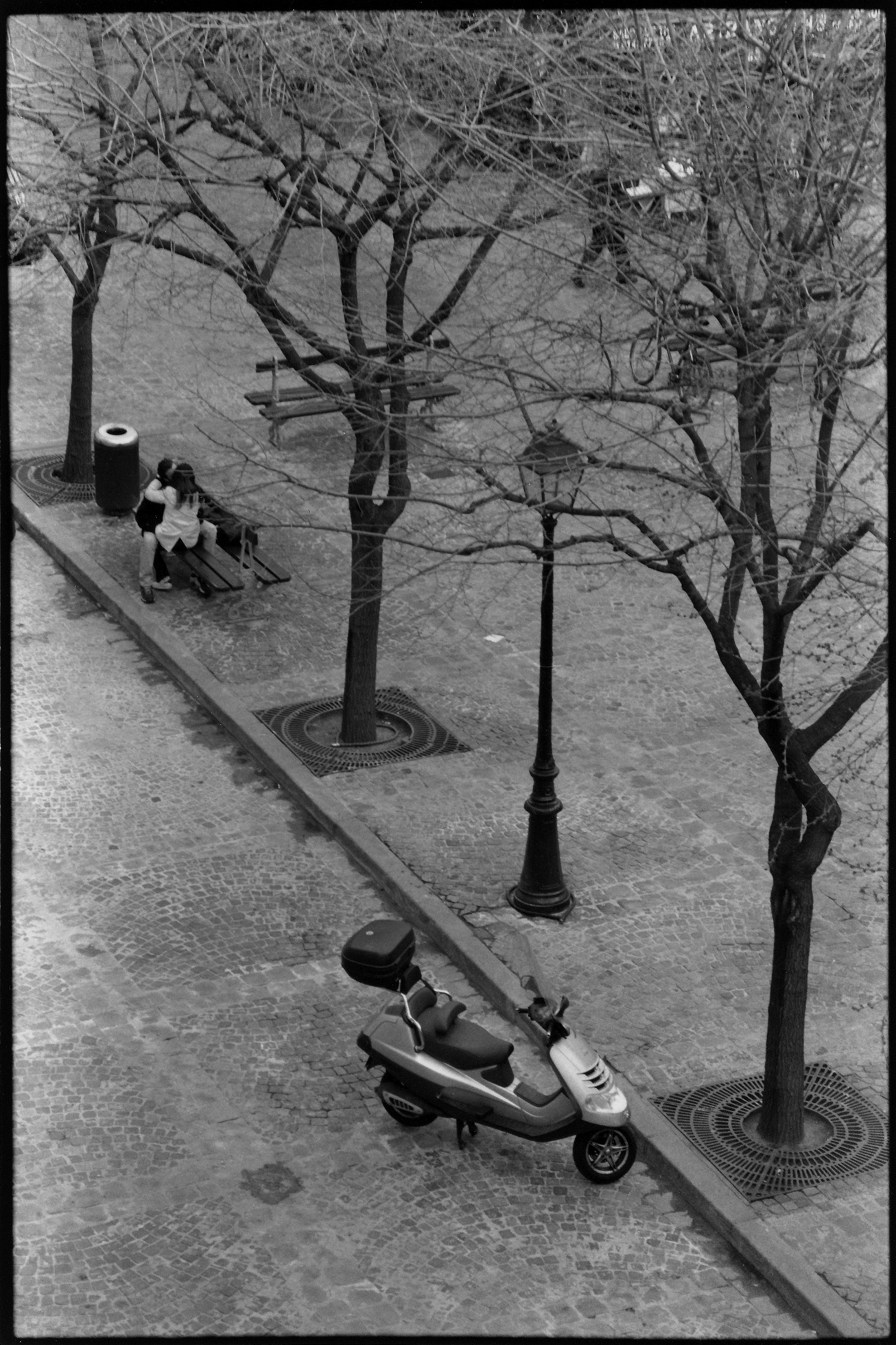

I walked all over Paris for the next few days, and everywhere I walked, there was love. In the Jardin des Tuileries young couples strolled hand in hand, like a postcard come to life. On the bridge over the Seine I pictured Audrey Hepburn and Cary Grant doing their uncertain dance in Charade. Among the gargoyles and asymmetrical towers of Notre Dame lurked the ghost of Victor Hugo’s hunchback with his Esmeralda. In the Louvre the busty nudes of Ingres and Samana turned my eye, and even the armless torso of the Venus de Milo held out the promise of love.

Earlier that day I’d tried to pick up a mime outside the Musée d’Orsay. She was dressed the part of a punked-out ballerina — crinoline tutu, leather bustier, pink hair — yet somehow still looked innocent. Without a note of music to accompany her, she danced first to classical ballet, then punk, then hip-hop, and then ballroom. I could almost hear the violins and the three-chord thrash she was moving to. I was so taken with her that I composed a message on the back of a ticket stub in my very broken French: “You are other than beautiful. Possible you want with me a coffee? It is not about words, because I am an idiotic American.” I gave her the note between acts. She read it but said nothing. She was a mime, after all.

Such was the character of my first few days in Paris: conjuring up Audrey Hepburn and passing notes to pink-haired street performers. My dreary hotel room wasn’t helping matters. I thought things would improve when my friend Jacques offered to let me stay in his apartment while he was out of town. Jacques was the leader of the Yes Men and the most feared anticorporate prankster in Western Europe. His apartment was in the working-class section of Belleville, in the shadow of the massive Hôpital Saint-Louis.

I went to meet him there on the morning of his departure. Following his explicit directions, I ducked behind the bistro on the right, passed through the narrow alleyway, climbed two rickety staircases (avoiding the Vietnamese caretaker at all costs), and there I was, standing in front of my very own free Parisian apartment. I knocked. Jacques opened the door — or half opened it; there were several cartons of books and a broken lamp blocking the way. (Jacques is gay but clearly lacks the propensity for cleanliness and nice furnishings.) I could just manage to squeeze myself and my pack inside as he gave me a big hug. “Voilà,” he said, waving an arm in a vague arc around what had to be one of the five most disheveled apartments in the history of bohemian squalor. Parts of several cannibalized computers littered the kitchen table. A pot of stale spaghetti languished in the sink. Books in three languages were stacked everywhere. There was barely room to turn around. Jacques himself was in a slight panic as he prepared to leave town: distractedly downloading files to his laptop and filling his own pack with what looked to be not particularly clean clothes. On his way out the door he handed me the keys, kissed me on both cheeks, and knocked over the already broken lamp, breaking it further. He smiled, his eyes gleaming, as if to say, The bourgeoisie don’t know what they’re missing. And he was off.

I looked in the fridge: six kinds of mustard and nothing to put them on. I hauled my backpack up the ladder to the cramped loft bedroom, its bed filled with DVDs, books, and the smell of sweat. It was probably good that Fiona hadn’t gotten back to me and the mime outside the Musée d’Orsay had ignored my note. Alas I was destined to be loveless in Paris. And, as sometimes happens when we’re alone and desperately want to be otherwise, my thoughts turned inward and grew morbid.

I’d survived twelve airplane flights since leaving New York. My next flight would be my thirteenth. I’m not a calm flyer to begin with. I like the view and the roasted peanuts, but the rest is existential torture. I enter into a personal battle of wills with anything worse than minor turbulence and am always amazed that the flight attendants have survived as long as they have. Given how many times I had flown of late, I was amazed I was still alive. Maybe this next flight would be my last. And why not? What was the point of living, anyway, without love?

Mulling over these thoughts in Jacques’ DVD-strewn, sweat-smelling bed, I had a dream: I am sitting in a car with my family — my mother and my mysteriously back-from-the-dead father and brother. We’re in our old ’72 VW van, one in a long line of cars strung out along a hill, all readying for takeoff. We are going to lift up into the air and fly to heaven. I am giddy at the thought. We are going to die. All of us. We’re gathering speed down the slope. Faster. Faster. Just as we hit the flatland, there’s a hairpin turn. The three cement trucks in front of us skid out of control. They will not make it. Our van slides, then rights itself, hits the straightaway, and rises into the sky. We are in heaven. We are dead. It is over. We can never return. It is not scary; it is simply serious: a fearsome, irrevocable passage, heartbreaking and final.

My thirteenth flight was just days away, and here I was, dreaming of taking off into heaven with two ghosts at my side. I don’t believe in signs, but this struck me as uncanny. As the day of my flight drew closer, I became increasingly convinced my plane would crash. It wasn’t just a “funny feeling”; it was a palpable sense of doom: I had only a few short days to live.

With this on my mind, I now saw death everywhere in Paris. The pope had died a few days before, and flags across the city were at half-mast. Every monument I visited aroused the ghosts of history’s nameless dead, casualties of the Revolution, the Bastille, the guillotine. I sought out death as only a tourist can, from Napoleon’s Tomb — ostentatious and overdone in red marble, imperial to the end — to the vast necropolis of Père Lachaise Cemetery, which houses the remains of Balzac, Chopin, and countless others. Death was also underfoot in the Catacombs, underground mines annexed in the 1780s to hold the overflow from Paris’s cemeteries. I wanted to take the tour, but it was closed for renovation. (How do you renovate the dead?) As I walked the streets of Paris, I imagined the twisting passageways beneath my feet, stacked with the bones of centuries.

Drunk on this mental cocktail of death, I found myself in the Sainte-Chapelle. Built in the mid-thirteenth century as the royal chapel and reliquary for the crown of thorns (yes, that crown of thorns), the Sainte-Chapelle is an eight-hundred-year-old masterpiece of late-Gothic architecture. Trashed during the Revolution, restored during the Restoration, it is also a microcosm of the history of Paris, beloved of tourists and locals alike. Gazing upward to an azure ceiling dappled with gold stars, I thought back to the heaven of my dream and pondered the idea of martyrdom, that strange urge to sacrifice oneself in service to the Divine. To my left were the Apostles, so worn with time as to be indistinct from one another. Before me was Christ on his throne, surrounded, oddly, by angels holding torture instruments. It made a certain poetic sense that Love would have led me to its dark twin, Death; and that Death, that great taproot of religion, would then have led me to this strange God and his sadistic angels, all of us gazing heavenward, struck dumb by the beauty around us.

I was there with many other sightseers, all of us poking about, chatting with companions, taking photos, and trying to follow along with a guidebook telling us how “on the right-hand-side archivolts there is a nice representation of hell, with imps.” Did this atmosphere make the Sainte-Chapelle any less beautiful? Not that afternoon. The air was charged with light, and I was filled with longing: a spiritual lust, if you will; a desire for release and union. I wanted to disappear into the light and air and colors and geometry of this place.

“If I find in myself a desire which no experience in this world can satisfy,” British author C.S. Lewis once wrote, “the most probable explanation is that I was made for another world.” For Lewis, a well-known Christian, this longing was proof positive of a divine Creator. I shared Lewis’s soulful desire but, for better or worse, could not take that next step with him. Lewis also believed that the Christian God had intervened directly in human history, which to me was pure crazy talk. To my mind it was the hard-eyed materialists — Karl Marx, Bertrand Russell, Mark Twain, George Orwell — who’d gotten it right. Napoleon, that greatest of French emperors, once observed that “religion is what keeps the poor from murdering the rich.” Sigmund Freud understood the Christian God as an infantile fantasy, an elaborate wish for a father figure who would punish us and set everything right. To his credit, Freud did acknowledge the human capacity for an “oceanic feeling” in which the boundaries of the ego temporarily dissolve and one experiences merging with a great vastness. Tellingly Freud had only heard of this from others; he’d never experienced it himself.

How strange, I thought, that the intelligence of a writer like Lewis and the skill of the unknown master craftsmen who’d given shape to the Sainte-Chapelle should be placed at the service of an infantile fantasy. Had they not asked themselves Epicurus’s ancient questions: “Is God willing to prevent evil, but not able? Then He is not omnipotent. Is He able, but not willing? Then He is malevolent. Is He both able and willing? Whence then cometh evil? Is He neither able nor willing? Then why call him God?” This, to me, was a slam-dunk for atheism. And yet, was I not a walking contradiction? Bereft of love and facing imminent death, I’d come to the Sainte-Chapelle a desperate pilgrim. And now here I was, so filled with “oceanic” longing that I stood on some sort of ontological cusp, vibrating at the edge of belief and nonbelief.

Just then the chapel’s PA system kicked in, silencing all of us tourists, who had been chattering away in a half dozen languages. “Ssshhhhhh,” said the voice on the PA, a long wordless breath that rolled through the chapel and seemed to come from everywhere and nowhere at once — as if some cosmic librarian, or Jesus in heaven himself, had placed his finger to his lips and kindly, with forgiveness for each of his imperfect children, asked us to be quiet. The muddled din of murmurs and careless side conversations (sins that, until that moment, we weren’t even aware we were committing) came to an abrupt halt. We were all brought up short, shocked into self-awareness and reawakened to the beauty around us. We felt chastised, but lovingly so, delivered from our transgressions and returned to an original state of grace: the glory of the Sainte-Chapelle in virginal silence, unsullied by our wanton chatter.

It took only a few minutes for the conversations to start again: softer, of course, then bit by bit a little louder. This cycle must have repeated itself all day long. But in that golden moment of silence I had felt something extraordinary, an uplifting in my heart. It brought me back to an afternoon then twenty years gone, an afternoon when Jesus himself had come calling.

It was the middle of a Michigan winter, and my girlfriend and I were living together in the side room of a friend’s weatherized garage. For whatever reason, I’d become depressed and emotionally shut off. That afternoon, while my girlfriend was at work, I got stoned and — as often happens — horribly paranoid. It was the kind of paranoia that feels as if the malevolent eye of the Universe is boring straight into you. An icy hollowness took hold of me and wouldn’t let go. My heart was clanging in terror. I wanted to run away, but you can’t run from the Universe. With nowhere to go, I took up a defensive kung fu stance. I didn’t know kung fu, but my body was making its own decisions. After a time my body deemed this stance silly and sat itself down: back upright, legs crossed, hands holding the knees. I breathed deep, stilling my nerves, seeking courage, and opening myself to the darkness and emptiness. I turned over my hands, which had been gripping my knees, and rested them with palms upward in a gesture of welcome and surrender. I thought: Love. I must choose love. And faith — in God or godlessness; it didn’t matter. Faith in faith itself! This would calm the fear.

I didn’t know to what or to whom I was offering myself up, but I could feel a heat move through my body: down my center, from my crown to the base of my spine. And I could feel a similar heat in my hands, as if I was breathing my fear, my pride, my whole shuddering self out of some aperture in my palms. I thought, I am having stigmata. And that’s when Jesus came to me.

In retrospect it must have been very good pot.

My eyes were closed — they had been this whole time — so I couldn’t see Christ, but I could feel him hovering over me, maybe fifteen feet up (which would have placed him on the other side of the garage roof). He was on the cross in a blaze of light, looking kindly down upon me, his arms spread against the beam as if it were the wings of some biblical jet pack and he might zoom away on it at any time. Rays of light were coming from his hands to my hands, from his feet to my feet. I was feeling his love, and I was comforted by it. At the same time I was incredulous. Didn’t he know I was a committed atheist? What strange tricks my mind was playing on me. Look what my desperation had conjured up.

Then I noticed something: the nails holding Jesus to the cross had been driven not through his palms but through his wrists. Such a detail would likely be of little concern to the average Christian caught in the throes of stigmata, but like an anthropologist still scribbling field notes as he’s being boiled alive by cannibals, I felt it mattered. Contrary to most depictions in medieval and Renaissance paintings, the Romans would have had to drive the nails through Jesus’s wrists to support his weight for three days. Was science trying to tell me my hallucination was real? Maybe I was having more than a vision. If I open my eyes now, I wondered, will there be wounds on my hands and feet? Yes, somehow I thought there would be. Even if this was all a psychosomatic event — an elaborate sympathetic reaction — still there would be wounds.

I opened my eyes: no wounds. My hands, though, were hot. And Jesus was still there, but also not there. No actual visible entity was shining down, changing the quality of the light in the room, but he was there in some other way, hovering exactly as I’d seen him with my eyes closed, radiating love, exchanging heat with my hands. It was a little while before the vision slowly dissipated.

I don’t know whether the Church fathers would have deemed this a miracle, but it did its work upon my soul. I was no longer depressed. I made up with my girlfriend. I was a changed man — if not for the rest of my life, then at least for the rest of that week.

In my moment of need that afternoon in Michigan twenty years earlier, I had called out for love and courage, and my call had been answered by a historically accurate vision of Jesus. But, stubborn rationalist that I was, I hadn’t come to believe in God or hell or angels or the Second Coming or Judgment Day or any of it. Instead I’d wondered why I had conjured Christ. If I was to have visions, why not a fiery Tibetan Buddha, or a Native American spirit animal, or some sort of secular-humanist infinity loop? Why had my personal slice of the collective unconscious turned out so Christian?

I thought of this at the Sainte-Chapelle, after that extraordinary moment when the voice on the PA caused us all to fall suddenly silent. My heart was reeling from the beauty of the place, and I was lifted in an impossible desire for union and self-destruction. I wanted to be undone. I wanted to impale myself on the window lancets. I wanted to have sex with the building. I wanted to die. And why not? I was doomed, wasn’t I? I wasn’t meant to return home. I’d come nearly full circle around the world. It had been a good run, but my next plane was going down, and it would soon be all over.

And that’s when I conjured Jesus once again. It wasn’t a vision this time but a voice: You have turned away from rare chances to be joined with God, the Voice said. Why? What are you afraid of? Don’t toy with God. Wake to him. This might be your last chance.

Whether this voice was indeed Jesus or just my imaginary-friend equivalent of Jesus — or simply a heart-rending appreciation for late-Gothic architecture — the questions were good, probably as good as those posed by Epicurus. “When a man knows he is to be hanged in a fortnight,” Samuel Johnson once said, “it concentrates his mind wonderfully.” The Voice had said: This might be your last chance. Was I actually slated to die? And if so, should I dutifully board my thirteenth flight or try somehow to evade my fate?

I had no answers, but over the next few days in Paris my mind was indeed concentrated wonderfully, and I made the most of it: a return visit to the Musée d’Orsay; the view from the Eiffel Tower; a bowl of bouillabaisse in a little bistro in the Marais. On my last afternoon I walked once more the lanes of Père Lachaise Cemetery, wandering among its stone monuments to the dead, some of them famous. Molière and Proust kept company here in the afterlife, along with American rock star Jim Morrison, who’d had the good (or bad) luck to die in Paris. Here was a monolithic bust of Balzac, towering over his tomb. Here was opera singer Maria Callas, whose ashes, the guidebook said, had been stolen, then recovered, then scattered into the Aegean Sea. (An empty urn was all that remained at Père Lachaise.) In the cemetery’s columbarium I found the cremated remains of Ukrainian anarchist Nestor Makhno, a man not mentioned on the tourist maps but who was at least semifamous for having led a decade-long guerrilla war against both the czars and the Bolsheviks. A group of Communard revolutionaries, those heroic socialists of the nineteenth century — before Stalin gave socialism a bad name — had made their last stand here. Falling back from headstone to headstone, the soon-to-be dead taking cover behind the already dead, they’d run out of ammunition and surrendered. They were lined up against a wall of the cemetery, shot, and buried in a mass grave where they fell.

Alongside all this Death was Love. Abélard and Héloïse, the first modern lovers, were here, a stone canopy over their heads, letters from the lovelorn tucked into their crypt. Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas were buried side by side, still inseparable. The tomb and statue of nineteenth-century journalist Victor Noir had become a fertility symbol, with visitors leaving flowers in his hat and rubbing — in fact, nearly rubbing off — the overlarge bulge in his trousers. Finally, as the cemetery was closing and the guards were shooing stragglers to the gates, I snuck over to Oscar Wilde’s grave: an ugly, art deco affair whimsically covered in the lipstick-laden kisses of his many admirers.

Before Sunset was in theaters that week, and I went to see it on my last night in town. Ethan Hawke and Julie Delpy play lovers reunited after almost a decade apart, with only a few hours together before Hawke’s plane leaves. If I were to fall for any actress, it would be Julie Delpy. As they wandered the streets of Paris and gingerly rekindled their lost connection, I was rooting for Ethan, but really I was rooting for me: Smile at me, Julie; sing Nina Simone to me; almost touch my hand.

And all those days I’d heard not a word from Fiona. Not even the courtesy of regrets. “The bitch,” I said again in my best Belmondo whisper, even though by then I’d recalled that what he’d actually said was “Life is a bitch,” and it was the policeman who had misheard him and conveyed the wrong message to Jean Seberg. In any case I plodded over to the Internet cafe one last time. And there it was finally: her reply. Her work e-mail had been down. She would love to come to Paris to see me. But here I was, leaving — nay, dying — the next day. Belmondo had it right.

A gray haze hung low in the sky that final morning. No deathly dreams had come the previous night, but I could not shake the sense of foreboding. I packed, slipped Jacques’ key under the door, and went to a nearby cafe. Jesus had the Last Supper; I had a Last Croissant. I headed to the airport in a kind of trance, as if carrying out the final rites before a scheduled execution.

On the check-in line I looked around at my flightmates as if we were all in an early scene from an airline-disaster movie: the audience knows the plane is going down as the director, with telling touches, introduces his doomed characters. The middle-aged couple heading home to New York: do they know they’ll never arrive? The family speaking German: will the mother cradle her child as the plane goes into its final spiral? The dramatic irony may be heavy-handed, but it works. Screaming horror awaits these people who are calmly setting their passports on the counter and innocently lifting their suitcases onto the scales.

My character wanted to go off script. Walk away, he was telling himself. Walk away now. Let the plane go without you. Yet I shuffled forward another few feet toward oblivion. Shouldn’t I warn the authorities? “Monsieur, this plane is going to crash!” I would exclaim to airport security. “But how do you know?” “Well, you see . . .” And they’d lock me up in the psych ward — or, worse, the terrorist ward. And then, if the plane actually did go down, in the psycho-terrorist ward.

At that moment the clouds of paranoia parted just long enough for the rational part of my brain to grab hold of Occam’s razor and make one last lunge at reason. What, really, was the simplest explanation here? Was it (1) a flying Volkswagen had come to me in a dream to warn me of my impending death? Or (2) the number thirteen — just a number, after all, with no calculable mass or documented history of intentionality — was about to exercise its agency in the physical world? Or (3) Jesus Christ, a dead man, had come to me in the Sainte-Chapelle and told me to change my life, and since I hadn’t, he was now going to reach out from beyond the grave and bring me to him? Or (4) my fear of flying, stoked by several unusual coincidences and an overactive imagination, had blossomed into a mild form of insanity. Occam, I had to concede, would have thrown his lot in with answer number 4. And somehow the conclusion that I was partly insane calmed me. My character played his role. I boarded the plane.

The number thirteen and mystical visions aside, flying for me has always been a rehearsal for death, a reminder that someday it will happen. I am doomed, I thought as we readied for takeoff — if not at that moment, then later. I would one day be as dead as all the souls buried in Père Lachaise. As dead as Oscar Wilde in his tomb studded with lipstick kisses. Kneeling at his graveside the day before, I had thought it a fitting monument to Love’s defiance in the face of Death. Lips in purple, blue, pink, and all shades of red kissing off Death. Yes, Mr. Death, said those lipstick kisses, you will have me in the end, but for now I lust, I sing, I burn.

Not knowing to bring lipstick, I’d slathered on my lip balm, knelt down, and placed my kiss among the others. The colorless impression I’d left had no doubt already evaporated, but I could still feel the rough, cold limestone on my lips. I could still feel the strange love that had reached down to me from the rafters of the Sainte-Chapelle. I could still feel the love of love that Paris had summoned in me. And all those loves made me ready for death, or more life, whichever was to come.

My flight, of course, did not crash. Instead it carried me safely to Reykjavík, Iceland. Some days later, after I’d hiked a few glaciers and soaked in several geothermal pools, another plane brought me safely home to New York — which meant I was still alive when Greenpeace called a few months after that and offered to fly me back across the Atlantic to do a training in London. “I’ll be staying with friends,” I said in my e-mail to Fiona this time. “Care to join us for dinner and what have you?”

Yes, came her reply by now-functioning e-mail.

I only half remembered what she looked like by this point. (I’d never seen her in anything but nun’s robes.) When she showed up at the Indian restaurant in northeast London in a loose white shirt, her hair falling to her shoulders, I saw and heard what the robes and precepts of silence had hidden. She was effervescent and wicked smart.

After dinner my friends dropped us off at a nearby pub with just twenty minutes left for a pint before closing. Our easy chemistry and sped-up conversation about infinity and language made me want to kiss her hard on the mouth. After the pub closed, we found the tube stop where I would catch a train back to my friends’ apartment. Fiona, however, could get home only via a long string of buses.

“You can come and stay with us,” I offered. “I promise I won’t put the moves on you.” Pregnant pause. “Unless you, ah, want me to put the moves on you.”

Laughter.

“Can I kiss you?” I asked.

“Well . . . I’m kind of seeing someone.”

Kind of, she said. But which kind of was it: “I’m kind of not interested in you”? Or “I kind of have a boyfriend — but only kind of — so I could sleep with you, but I kind of haven’t made up my mind yet”? Or did she mean “I have a very real boyfriend, but I’d happily cheat on him because you’re kind of a sex god — but you have to kiss me right now, so I can kind of pretend it wasn’t my fault”?

“You see,” I went on, “it’s just that most of the night I’ve been imagining kissing you.”

“It crossed my mind a few times too.”

“Ergo . . .”

She laughed but made no move. Nor did I.

“Are you sure you’ll be OK taking all those buses?”

“I’ll be fine.”

I kissed her on the cheek, and we went our separate ways.

My friends and Fiona and I got together again the next day, this time for beers and pub food on Fleet Street. Afterward Fiona and I headed off to the Soho clubs, and it was pretty clear by then that she’d kind of made up her mind that she was only kind of seeing someone else, and I kissed her, and she kissed me back, and we danced to God knows what Euro-trash club music and we drank too much vodka and we drank too much beer and in the morning I almost missed my plane.