Aunt

My nephew is named Jesus. No accent mark over the u. Just plain Jesus. I’ve never met him. He was whisked from my sister, still wet from the gentle wash of her womb, into the loving arms of the state before anyone could say, “Holy mother of God.”

Before

When I was six, Sophia lay with me on our parents’ bed and taught me how to color in a coloring book. Lying there on the puffy navy blue comforter, beneath the curved birch headboard, I felt as if we were on a raft at sea, going to where the Wild Things were. Sophia took the book from me. “Look.” She held up a crayon. “You draw your own line inside of their line. Like this.” She demonstrated with the aqua crayon, tracing the black line of the cartoon boy’s sweater. I concentrated. “Then you just color inside your line. That way you’ll never go outside.”

Cords

Sophia called from Berkeley, ostensibly to wish me a happy eleventh birthday. If I was eleven, she must have been twenty.

We had a cream-colored wall-mounted phone, its cord gray with dirt. I waited for my mother to finish her conversation with Sophia and hand the receiver to me, but she never did. “We were just going to leave to take Anne to her birthday dinner,” Mama said into the phone. “Oh, Sophie, what do you mean?” Long pause. “I don’t know what you’re talking about.” The long, curly phone cord stretched out straight as my mother walked from the kitchen into the laundry room, where the concrete floor had stains from all the times the washer had overflowed, rings overlapping each other like the foam marks of waves on sand.

My father sat at the table with me, rapping his keys on the surface. “Do you want to talk to Daddy?” Mama asked. She came back to the kitchen and handed the phone to my father. “We might not be able to go to dinner,” she said to me in a low voice.

“Are you out of your goddamned mind?” my father yelled into the phone. “Jesus H. Christ, we’re coming to get you!” Pause. “I don’t care if it’s Anne’s birthday. There are no goddamned aliens.” He handed the phone back to my mother, and the curly cord swung like a pendulum after she hung it up. I went into the living room, where I would spend the rest of my eleventh birthday alone, eating Apple Jacks cereal for dinner, waiting for my parents to return home with my big sister.

Drugs

Before, she took LSD, mushrooms, pot.

Now she takes Haldol, Seroquel, Cogentin, Thorazine.

Extrapyramidal Symptoms

A technical term for a patient’s inability to remain motionless. Sometimes the result of long-term antipsychotic-drug consumption.

Sophia has “pill-rolling” tremors, her index finger and thumb bumping and smoothing each other, her hands and feet and fingers always swatting, kicking, jerking.

Finances

Until my sister was twenty-three, my parents were her conservators, paying all her hospital bills and managing her meager Social Security income. She lived in her own apartment, with our parents paying the rent. It was only blocks from our house and, like all Sophia’s apartments, always smelled sour and exotic, as if milk and curry had done something bad together in a corner. Sophia thought our parents were stealing money from her, and eventually they let the county become her conservator, giving up the right to direct her medical care.

It seemed unfair: she went crazy, and people took care of her; I stayed sane, and I had to work.

Guilt (A Partial List)

My mother favored me, and everyone knew it.

I am only neurotic, not paranoid schizophrenic.

I took drugs, and nothing bad happened to me.

I don’t visit her often enough.

I don’t remember which year she gave birth. I also don’t know who fathered her baby. (She said it was God, or another patient, or perhaps both.) I wonder whether she tongued her forced birth-control pills or if they simply failed. I should know all of this.

I used to hope for a cure, but now I hope only that she’ll die painlessly.

Sometimes I use her illness as an amusing conversation starter.

Sometimes I use her illness as a way to be a victim.

Hospitals

As a nurse I’ve spent much of my life inside hospital walls. I feel at home there. I know the smell of an acute-care hospital — disinfectant and death and deodorizing air freshener — in comparison to the smell of a long-term-care hospital: sweat and urine, the scents of the senselessly alive.

Sophia lives forty miles from my home in a long-term-care facility. She has curly gray hair, on both her head and her chin. Sometimes someone shaves her, but most days it looks as if she had two tarnished nickels on her jowls.

When I visit her, I become a child again. I’ll always be nine years younger. Her almost toothless mouth yaps continually that I am bad, stupid, wrong because I don’t believe her hallucinations. She senses my unspoken disbelief and continues her attacks: “No one ever cared about you, Anne. You were an accident.” I know she is saying this because our parents treated me with care — or, at least, more care than Sophia wanted them to. Sometimes she calls me “Nurse Ratched,” after the sadistic head nurse in One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

But the last time I visited her, Sophia asked me suddenly, “Do you want a job?”

“You mean here?”

She nodded vigorously, eyes wide. I’m unsure why she wanted me to work there. It’s possible that she craved connection. It’s also possible that she thought I would grant her favors. Or maybe a little of both.

“No, no,” I said. “I have a good job at another hospital.” I actually work at the same hospital where Sophia was first hospitalized when I was eleven. When I started working there, I didn’t even recall the building from the outside, and I felt only a hint of recognition as I strolled the halls. Anticipating a familiar sight just around a corner, I would be confronted with nothing I remembered. I began to believe that the hospital had torn down the psychiatric unit during the intervening decades. Then a co-worker told me that the psychiatric unit had been turned into the pediatric unit; the day room had become a playroom.

I began to remember: Here was the hall where the doors used to lock loudly behind me. Here was the day room where Sophia would meet us, now occupied by bald children in brightly colored hospital-issue pajamas, wandering around with their IV-pole dance partners, like genderless gnomes.

I’m the night-shift nursing supervisor, overseeing the entire hospital, placating both the staff and the people who rely on us for care. Recently I was called to the emergency room to help with a patient who was on an involuntary psychiatric hold — a legal order to confine a person whose mental state makes him or her a danger. This patient had taken the cord to her heart monitor and tried to hang herself with it. The sea of green scrubs parted as I came in.

“Hi, my name is Anne, and I’m the nursing supervisor.”

The patient, who was seventeen and had the beginning of a bruise on her neck, spit in my direction. “I don’t give a shit who you are. You. Have. Fucked. Me. Up.” She pointed her middle fingers to her temples, in rhythm to each word. “You. Have. Fucked. Me. Up.” A nurse behind me made a move with a set of restraints.

“She’s a minor,” I said as quietly as possible over my shoulder to the nurse, who gave me an angry look. Spit from the patients, disdain from the staff.

“They’re telling me to die, ugly bitch. And. You. Have. Fucked. Me. Up.”

“Who’s telling you to die?”

“They are! They are!” Her arms began to shake on the shiny bars of the gurney. “Let me die.” Her irises were indistinguishable from her pupils. For a moment she looked like some memory of Sophia that I had forgotten, some sliver of anger and loss that lives in hospital walls and accompanies me invisibly on my midnight rounds.

Involuntary Holds

There are three types of involuntary hold in California: three-day holds, fourteen-day holds, and more permanent conservatorships, which are renewed annually via court proceedings. And, of course, there are other forces that hold us involuntarily, invisible and inviolable at once.

Jealousy

Sophia thinks that I slept with her boyfriend when I was thirteen.

Sophia also thinks I seduced and had sex with our father, and wishes that she had.

Key

Sophia’s facility is similar to a convalescent home, except that all the doors are locked. I tell the woman behind the reception window who I’m visiting. She looks up Sophia’s name, then slides a brass key beneath the glass. I use it to open a heavy metal door, and I walk into a wall of urine scent. The smell is so strong that I expect the air to undulate in front of me, like gasoline fumes. This first ward is a unit for the elderly and insane. An old woman with white hair down to her shoulders stares at me, her toothless mouth open, as I walk past. In a few years Sophia will probably be moved to this ward.

I use the key on another door and walk into a ward with people who are just crazy, not old and crazy. I try to blend in, to make myself — and the key in my hand — invisible. A man in a maroon sweat shirt is squatting in the tiled hallway, saying, “Box it up for me, box it up,” over and over. A woman in her fifties drags her right leg behind her as she faces the wall, crab-walking. I can’t put the key in my pocket because I don’t want to make it obvious by the action that I have a key and they do not. In a mock move to pull up my pants, I slip the key into the front of my jeans. The squatting man and the crab-walking woman continue to ignore me.

Legs

Sophia has been in a wheelchair for at least ten years. No one seems to know why. The last time I visited her, she heaved herself out of the chair and walked about ten feet to the bathroom. Her gait seemed steady and even. When she returned, she wiggled into her wheelchair again.

“So, what’s wrong with your legs?” I asked her. “Why do you need a wheelchair?”

“What’s wrong? Let me tell you! In the middle of the night, every night, they come in here and hack off my legs. Oh, it’s awful.” Her face contorted. “Just awful. Hack, hack, hack. My roommate never even wakes up while they do this. And then they open up my stomach.” She held up her round belly with both hands. “And they take everything out. All my insides. Stomach, liver, intestines. Oh, they butcher me like a cow.” She shook her head. “And then in the morning they come back. Every morning, just when the sun is rising. They put everything back into my stomach. You have no idea how much that hurts. They stuff it in. And then they screw my legs back on. I don’t even know if they’re my legs. I don’t think they are. But they just screw them on, the way you put a leg on a table. That’s what’s wrong with my legs.”

Molestation

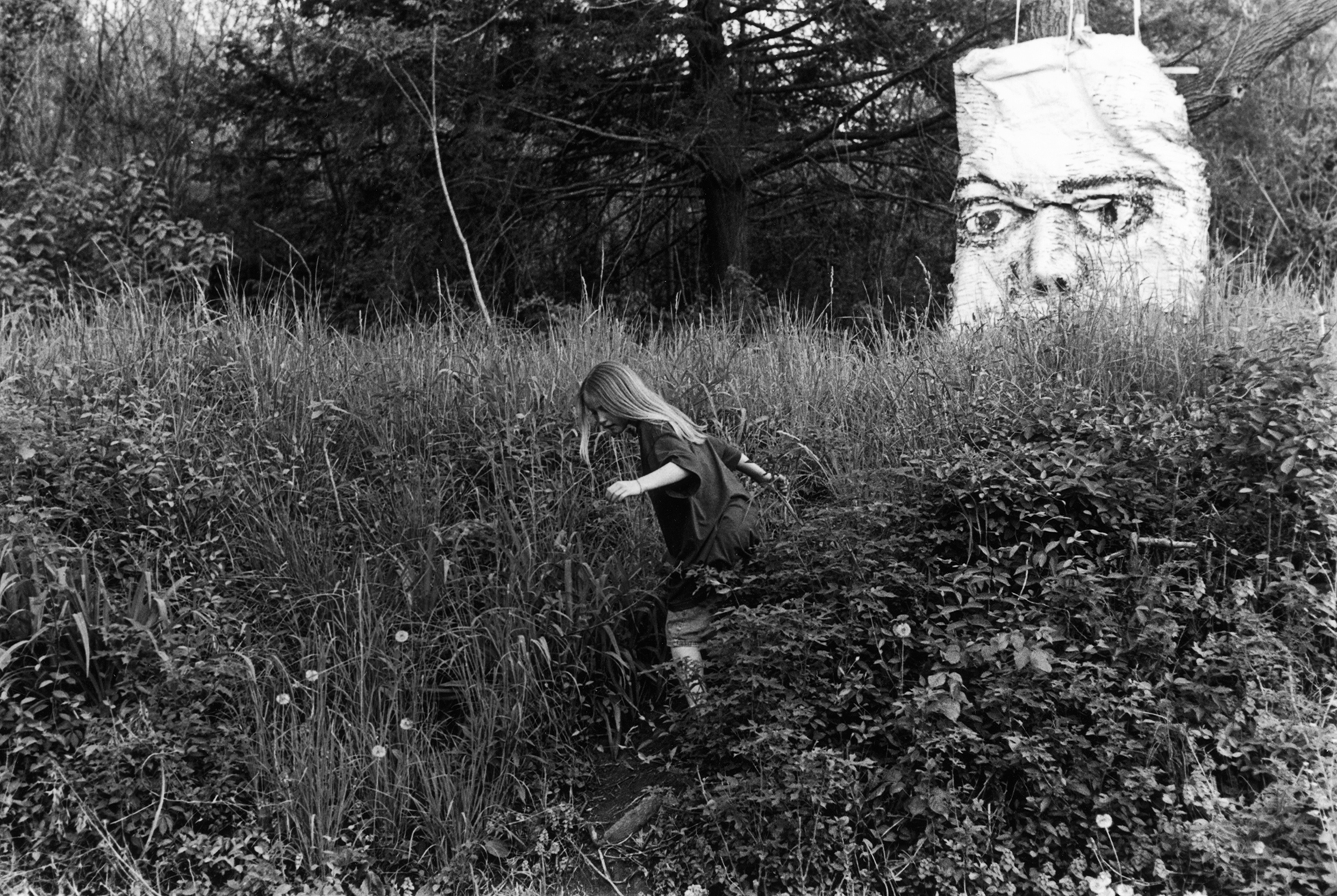

My mother had transformed Sophia’s bedroom into an office after my sister had left home. So when Sophia returned, before she went into the hospital for the first time, she shared my bed. I was eleven, and Sophia ran her hands down my side every night, inching closer and closer to my genitals until she found them. My mother, the sexologist, had taught me about sex by tossing a pamphlet from the doctor’s office on my bed when I was seven. Since I was an early reader and had already found my mother’s copies of The Happy Hooker and A Study of Prostitution in Mid-Century America, I ignored the booklet, with its simple drawings of fallopian tubes and vas deferens. I knew the word for what Sophia was doing to me, and I knew what I was supposed to do, but the difference between real life and theoretical life was that, in real life, I was afraid to tell my mother.

About a month after the molestation started, when it had become obvious that it wasn’t going to stop, my discomfort outweighed my fear, and I resolved to tell. Mama was in her office, where the only window looked out onto a dead garden. A huge metal bookcase divided the room in half, shielding Mama’s desk, stacked with papers, from the door. I couldn’t see her, only her outline between the shelves. There was no place for me to sit.

“I need to tell you something,” I said. “About Sophia. She’s, uh . . . she’s touching me.”

Mama was silent for a long while. I wasn’t sure she’d understood.

“You know,” I said. “In a bad way.”

Silence again. Then: “Yes, I think she told me something about that.”

I stood, looking at the black metal bookcase, waiting for her to say more. When there was no other response, and her fingers began to pound once again on the keys of her Underwood typewriter, I turned and left. My mother typed one hundred words per minute, as she was proud to tell anyone. She’d been the fastest typist at the Maritime Commission during the war, the fastest typist she’d ever met. The staccato sound of the keys carried all the way up the stairs to my bedroom — clickety-clack, clickety-clack, her fingers rushing to type words about sexuality for someone else to read.

Napa

When I was twelve, I learned that state-run locked wards look almost exactly the way they do in movies, with the doors banging shut loudly and permanently, like prison doors. Whenever we visited one, I worried that I would somehow get separated from my parents, and the nurses would think I was a patient.

Psychiatric hospitals smell like a locker room where the janitor is on strike. Only the most basic needs of the residents are met. Teeth with cavities are removed rather than repaired; clothes are handed out from some bag that even Goodwill has cast off, filled with stained red sweat shirts and tiger-striped pants, everything too small or too big. Patients do the “Thorazine shuffle,” a kind of depressed dragging of the feet that barely propels them forward. Sometimes, inexplicably, a patient will scream, and the nurses will look up briefly. It takes more than a scream to set their feet in motion, though, and when they do move to patients’ sides, it is usually to admonish them to be quiet, not to comfort them.

I remember visiting Sophia at Napa State Hospital, where she was held in the maximum-security ward. I was sixteen. During the ninety-minute car ride, my father chatted with other ham-radio operators on his mobile radio. When we arrived at Napa, my mother got out of our Volvo station wagon first, telling Daddy to hurry.

The hospital looked like an asylum from a horror movie. There was a steeple, and every window had bars across it. We went into the lobby, where a receptionist asked if we were carrying any pencils or pens or pocketknives — to a patient hell-bent on hurting someone, especially herself, a pen is as good as a razor blade. The woman pushed a button and told us to follow the white-tiled hallway to another door. Then, finally seeing me, she asked, “How old are you, hon?”

“Sixteen.”

“Oh. Sorry. You have to be eighteen to visit.” The woman shrugged. “It’s the rules.” And so, just as on the night Sophia went crazy, I waited. No Apple Jacks this time, just three-year-old Reader’s Digests and a blue plastic seat digging into my thighs.

After a few weekends the receptionist began to allow me into the wards. There were no cells with padded walls and high windows, but there was a glass-enclosed area for the nursing staff, as if they were zookeepers and everyone else — patients and visitors alike — were the zoo’s residents.

I spent almost every weekend of my adolescence visiting Sophia in some mental hospital or another, most of them hundreds of miles from our home: Napa and Patton and Coalinga. She was moved repeatedly for no apparent reason. Sophia mostly refused to speak to us, sitting mute through our half-hour visits in the cafeteria, taking small sips of water from a plastic cup and only nodding her head yes or shaking it no to direct questions. She didn’t speak to us — or to staff, or her psychiatrist — for almost two years.

Obligation

My mother died when I was forty-five. When I called Sophia to tell her of our mother’s death, she said, “Ding-dong, the witch is dead,” and I felt so angry that I didn’t even ask if she wanted to attend the funeral. Let her grieve on her own, I thought, with all the other crazies. I have that power in our relationship. I hold the keys now.

Our parents were both only children. We have no aunts, uncles, or cousins. All but one of my grandparents died before I was born, and my father’s mother died when I was young, before Sophia went crazy. My father died of a heart attack when I was twenty-two.

Now I’m the only one left to visit Sophia. I drive forty miles to her locked facility about once every three or four months. There’s not a lot to talk about with a paranoid schizophrenic who hasn’t lived in society for decades. She doesn’t read books or watch films, has never owned a CD player or a cellphone. So we end up talking about her legs.

Parents

Shortly after my eleventh birthday my father disappeared into the garage, where he surrounded himself with ham radios, reemerging only to yell at me, it seemed. He’d accuse me of deliberately setting the table with the butter knife he hated, or of making the cat shit in his shoes. I was a disappointment, the reason he stumbled on the steps or overslept. The whole house was awash in blame, and although I wasn’t always the one at the end of his accusing finger, I was his target often enough.

I thought that if I were a better, kinder, smarter daughter, he would become like everyone else’s father. “He hates me,” I would cry to Mama, and she would say, “No, no, he loves you. He just can’t help his moods.” She tried to explain him to me, to help me forgive his volatility: “Imagine being raised by a crazy mother. It couldn’t have been easy for him.”

Some people remember their parents arguing about infidelity or money; I remember my parents arguing about who was to blame for Sophia’s insanity. My father’s mother was crazy, my mother said, and Sophia’s illness was his genetic legacy. My father said Sophia’s insanity was due to a lack of maternal affection. It was a nature-versus-nurture debate, right there in my own living room. I didn’t care who was right. I was too busy worrying that one day, with no warning sign, I’d find myself on a phone, begging my parents to save me from the aliens that lived in my closet.

Mama wasn’t as compassionate toward Daddy after they’d fought. Instead she would ask me to kill him for her. It was a game we played, a dance we danced. Mama would cry, and I would comfort her, repeating to her how mean he was.

“He’s sick, a sick man,” she’d begin. “So angry.” The tears would drip off her nose. “I just can’t live like this anymore,” she would say.

That was my cue to say, “You should divorce him. Please. I hate him.”

Her response was always that she couldn’t afford a divorce. “We’d be poverty-stricken, just like I was growing up.” She’d look at me, the tears starting to ease up. “You don’t want to be poor. You’d hate it.” I’d imagine myself as a beggar girl reduced to rags.

Then she would propose her solution: “You could just smother him with a pillow, and I’d tell people he died in his sleep. And if you got caught, you wouldn’t go to jail, because you’re a minor.”

I would play along, sketching the scene with her: me sneaking into their bedroom in the middle of the night, laying a fluffy pillow over his snoring head, and pressing down, down, down, until his struggling ceased.

Her tears would end, and we’d talk about something else, spent and sated by the secret story we’d spun.

I remember the last time she asked me, one awful August day, out in the summer-yellow yard. “I’d never ask Sophia to do this,” she said. “She’d tell Daddy. I know that I can trust you. You hate him as much as I do. He can’t help who he is, but he’s never going to change.”

The grass was dead, the sparse trees brown with the valley heat. The two of us sat on aluminum lawn chairs with green-and-white polyester webbing. I remember my mother’s desperate tone of voice. I was sixteen; she’d been cajoling since I was eight. But even though my hatred of my father had grown with age, so had my uneasiness with the idea of murdering him. Even talking about it was beginning to feel wrong. But I based my opposition that day on a practical matter: I protested that I didn’t think I was physically capable of holding him down while he suffocated.

I don’t believe she was a bad mother. She took me to see plays in San Francisco, whereas many of my classmates never left the county. She told me that my father’s abuse wasn’t acceptable. She taught me to read the New Yorker and the Nation, gave me a legacy of intellect. She wasn’t trying to do me harm. She was trapped in an unhappy marriage to a raging, inconsistent man, and she turned for help to the one person who loved her unquestionably: me.

I explain her actions, and I forgive them. That is who my parents shaped me to be: an explainer and a forgiver. It could be worse.

Queer

Sophia met my ex-husband, Lester, when I was still married to him. She’s also met my new spouse, Catherine. She came on to both of them.

Remembering

My sister remembers my childhood better than I do. She can tell me the name of the restaurant we used to frequent. I barely remember the restaurant at all, let alone its name. I seem to lose an old memory for each new one I add, as if my mind can retain only a finite amount, forcing me to sift and choose. Sophia, on the other hand, can render scenes from our past that I could never recall on my own, because she has so few new experiences to add to her meager supply of old ones.

Remembering can also mean to re-member. Our past is dismembered by time, but my sister’s recollection re-members it. She re-places us into the parts we once played: Mama in the Studebaker, driving to Mexico with the rest of us as hostages to her frantic freeway chauffeuring; Daddy rolling, laughing so hard he cried, on the newly seeded grass with our neighbor’s basset hound; herself on her friend’s sailboat, her fine curly hair whipped to cover her eyes like a blindfold; me as a toddler, munching dog biscuits in the spacious cabinet under the sink.

Sophia’s memories are so sharp, so detailed — in contrast to her delusions, which are cloudy and vague — that I have made them my own: the Studebaker was gold; Daddy wore his white leisure suit; I yelled at the dog to stay away from the dog biscuits I was eating. I am relying on an insane sister’s recollections for a portrait of my past.

Saint Sophia D'Illuminati Gnosis

This is how my sister signs her name.

Transference

I tell people that I fell into my profession by accident, choosing to go to nursing school after I’d dropped out of college. That story discounts the opportunities that nursing has afforded me: to worry about others’ well-being while overlooking my own; to keep my distance from my emotions while focusing on the horror that surrounds me. I am comfortable with other people’s tragedies. I cry for parents who lost their toddler to a tumor. Please, let me pour my compassion onto you, so that I don’t have to think about myself, so that I can pay no mind to those people behind the curtain — Mama, Daddy, Sophia, me.

Uncertainty

No one gives me my sister’s medical information, but nurses have insinuated to me that Sophia is diabetic. Nevertheless I have more than once brought her a half pound of See’s chocolates and watched as she ate all of them. It is not that I want to kill her, only that I believe her life has no meaning.

Vesepheron

Sophia was in a board-and-care home for five years, a place that offers more freedom than an institution. Able to leave on a day pass, Sophia would traverse the city on a bus before returning to that nondescript house. One evening, though, I received a phone call from a social worker, asking if I was related to Sophia. My sister had spent the previous night rolling on a neighbor’s lawn, naked, and the police had brought her to the county psychiatric-crisis center.

Catherine and I went to visit her. It had been several years since I’d been in a mental institution. The plush carpeting, the beautiful shaded green windows, and the palatial dining room that doubled as a visiting area were a stark contrast to the aging, yellow-tiled buildings of the past.

“This place is nice,” I said.

Sophia shrugged. She was wearing a salmon-pink sweat shirt — not a good color on her — and a pair of white sweat pants with brown bloodstains on the back. She eyed Catherine, then coyly smiled and lowered her lashes.

At the table next to us, a young patient stared at some invisible spot on the wall while his mother jabbered incessantly and tried to spoon food into his closed mouth, and his father gazed sadly at him.

I noticed that no one was smoking. I’d never been in a mental institution without a haze of cigarette smoke. I expressed my amazement at the smoke-free room, and Sophia gave me a look of complete pity. “They don’t grow tobacco on the planet Vesepheron, Anne. Vesepheron outlawed it on my behalf.” She said this with such condescension that I laughed, and then she added, “It’s hard to be a saint.”

Weird

My mother, when I would badger her, would tell me that Sophia had shown no signs of mental illness until that day in 1970. “She was just weird,” she’d explain. In our family weird was normal.

X = A+B∆+4a

I usually bring my sister art supplies: paintbrushes, pastels, watercolor paper. She has a bedside table and a small closet in which to store any personal items. All of her worldly possessions would fit in a grocery bag.

The last time I visited her, there was a stack of papers on the bed, about a hundred pages. I picked one up, thinking it would be artwork. Instead I saw letters and numbers and symbols written in neat lines on both sides of each page.

“Put that down,” Sophia hissed.

“What is it?” I asked, placing the sheet back on her bed.

“The CIA has asked me to work on chemical equations for them. I can’t say more.”

I offered to bring her a book on chemistry the next time I visited. I wanted her to know that someone supported her interests. She tilted her head while she considered the offer. Then she did something she’d never done in my presence before: she had a conversation with an imaginary person.

“She wants to bring me a book on chemistry. In case there’s something you can’t — or, more likely, won’t — teach me.” Pause for reply. “Well, I know. She means well.” Another pause for another reply. “Oh, she can’t help it. She’s bright but not that bright.”

In the end her invisible conversation partner decided that Sophia didn’t need a chemistry book.

Yin Chung's Chinese Express

On one visit I brought Sophia some sweet-and-sour chicken and a brandy-fried chicken drumstick. I made the mistake of arriving at lunchtime, when all the other patients could see that I’d brought food, and they began to gather around our table in the day room.

A woman wearing an orange shirt and bright-yellow sweat pants sat down to Sophia’s left. Sophia lifted the chicken leg to her mouth and, with manners born of forty years of institutionalization, let large pieces of meat drop from her lips while she ate. The second she lowered the drumstick to her plate, the woman on her left blurted, “Are you done with your chicken, Sophia? Are you done?”

Sophia, lips still dripping, didn’t even turn her head. “Go to your room, Lorraine!” she said, as if she were an angry mother. Lorraine looked at the chicken. Sophia lifted the leg to her mouth again, took another large bite, and returned the drumstick to the plate.

“Are you done with your chicken, Sophia? Are you done?”

“Go to your room, Lorraine!” Sophia repeated.

I secretly rejoiced that someone besides me knew Sophia’s name.

Zoo Visitors

My parents shuffled me off to a psychiatrist when I was eighteen, hoping to ward off any mental illness that might have been poised to strike. I’ve seen a therapist at least a few times a year — and sometimes daily — ever since. When I was twenty, I served my own time in a mental hospital for severe, debilitating depression, a condition that in some form has hounded me ever since. I have spent most of my life recovering from my life.

My parents came to visit me when I was in the hospital. Sophia did not. She was in Coalinga State Hospital, or Napa, or Patton.

The hospital where I stayed was clean and light-filled, a temporary habitat for the temporarily insane. But the day room still had a glass-enclosed area where the staff huddled, watching the patients, just as in every other mental hospital I’ve ever seen. And there were still rules: we were not allowed to eat in our rooms; we had to make our beds every morning; group therapy was mandatory, even for the patients who, like me, could only stare at the walls, too depressed to cry. In comparison to the many state-run facilities in which Sophia had resided, however, the small unit was sumptuous, the San Diego Zoo compared to a low-rent traveling circus.

Daddy sat straight-backed, angry to be in one more sanitarium. Mama was a hump of sadness in the chair next to him. The only thing I remember saying to them then is, “I’m not in the locked unit.” I could leave the hospital whenever I chose, reenter my life where I’d left it. I wasn’t yoked to the world of the insane. We sat like three stumps in the tasteful beige visiting area, Daddy with his silver mutton-chop sideburns, Mama with her big pink plastic glasses, and me slumped with depression, all of us remembering the fourth member of our quartet, tethered to her even in her overpowering absence.