This interview originally appeared in Medical Self-Care magazine, one of the best publications on health in this country. Tom Ferguson. a graduate of Yale Medical School started the magazine in 1976 as an “access to medical tools.” It’s a bridge between the medical establishment and the more unorthodox approaches of the wholistic health movement. In-depth articles and interviews, along with concise and readable book reviews make this a magazine well worth reading. (Ten dollars a year for four issues, Medical Self-Care, Box 717, Inverness, Ca. 94937.)

Tom writes: “Ken Pelletier holds a Ph.D. in clinical psychology from the University of California at Berkeley. He is a clinical instructor at the Langley Porter Institute of the University of California School of Medicine, San Francisco, and Director of the Psychosomatic Medicine Clinic. He is co-author (with Charles Garfield) of Consciousness East and West (Harper & Row, 1976) and author of Mind as Healer, Mind as Slayer.

Ken has spent most of the past ten years teaching people to prevent stress disorders. As he answers the front door of his redwood shingle house in the Oakland Hills on a bright June morning, he looks as if he’s been following his own advice.

He waves aside my apologies for being late and leads me into a spacious spotless office overlooking a lower level of the house. There is a wide, deep desk with an answering machine and a long bookcase full of perfectly straightened books arranged by subject. When I compliment him on his impeccable workspace, he smiles and leads me down a short hallway to his ‘working’ office a cramped, messy little room strewn with books and papers.”

TF: How did you first get interested in the ways the mind and body interact?

KP: I guess it was when I took a meditation course on the Berkeley campus in 1967. We read the Bhagavad Gita, the Autobiography of a Yogi, and did a lot of meditation. It got me interested in what optimum health was, and how it could be achieved.

TF: Most of your writings since then have centered around stress. How did you get from meditation to stress?

KP: The meditation interest led to some research on meditation at the University of California School of Medicine in San Francisco. This was still back in the days when we weren’t sure if people really could regulate their autonomic nervous system.

We decided to look at people who seemed to have an unusual degree of control of autonomic functions — yoga adepts and experienced meditators. We hooked them up to our machines and found that they really could control their brain waves, their heart rate, their blood pressure. At that point it struck me that many of the disorders I was seeing clinically might be problems in which a person’s autonomic nervous system is just completely out of control.

TF: You thought the same kind of training might help your patients?

KP: Yes. We asked the yogis and meditators how they’d learned to control their pulse and so on. They said it was just a matter of practice — like learning a new sport or a musical instrument.

TF: What other things could they control?

KP: Brain waves, blood pressure, heart rate, skin conductance, muscle tension, peripheral circulation, and respiration pattern and rate. Besides just looking at these individually, we fed all these simultaneous readings into a computer and looked at the relationships between them.

We were struck at the degree to which our subjects’ patterns were very coherent — when one went up, they all went up. When one went down, they all went down. The systems that controlled all these very different functions were very highly integrated.

TF: How does that compare to a normal person’s response?

KP: Non-adept individuals were much more fragmented. Their heart rate would increase, yet their muscle tension would be very low; or their skin conductance would show a big change, but their brain waves would remain the same.

TF: As though their different regulatory systems were out of touch with each other.

KP: Exactly.

TF: If the adepts were more coherent than normals, how did normals compare to people who already had illness problems?

KP: I think it’s mostly just a matter of degree. People who’ve become ill have gotten even more disrupted in their level of functioning. In this context, the adepts could be seen as people who were physiologically super-healthy. So recently I’ve gotten interested in how one can move from a state of average good health — and all that really means is that you’re going to get sick, grow old, and die along with everyone else of your age, sex, and weight — to a state of more than average health.

When you go through an annual physical and your doctor pronounces you healthy, that only means you’re average. The really exciting question, and one that a lot of people are beginning to ask, is how can you become more highly integrated than average, in the way that the adepts and meditators certainly were.

TF: Could you give an example of how someone might develop an illness as a result of the kind of imbalance you’re talking about?

KP: Whew! It took me a whole book to try to do that! What I tried to do in Mind as Healer, Mind as Slayer (see review on page 12) was to show how we move from a state of relative health to a manifest disorder. That’s where stress comes in.

What we found in our research is that there are two kinds of stress, short-term and long-term. Short term we can take. That’s the kind we share with every other biological organism. We react in a certain way when we’re in a threatening situation.

TF: Like when I came to the branch in the freeway on the way over here — and didn’t know which way to go.

KP: Exactly! So what was your experience at that point?

TF: Well, I realized I didn’t know which turn to take, so I decided just to stay in the lane I was in. After I was past the junction, I let out a long breath.

KP: You had a feeling of relief, of release?

TF: Yes. The point was passed. Even though, as it turned out, I’d chosen the wrong turn.

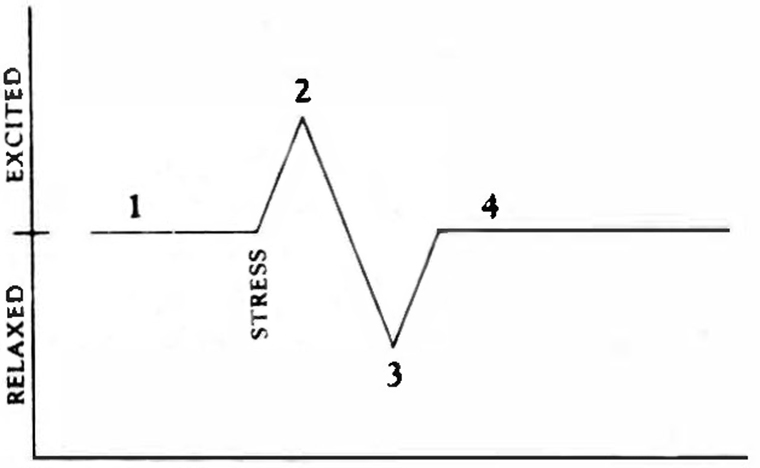

KP: That’s what happens with short-term stress. You encounter a stressor, you deal with it, and then there’s a period of relaxation. If we’d had you hooked up to a monitor when you came to the branch in the freeway and looked at your blood pressure or muscle tension, we would have gotten a curve that looked something like this:

Point 1 is your baseline level before the stress. Point 2 is the stress reaction that’s been so well described by Selye (see review of The Stress of Life, page 13). It corresponds to the firing of the sympathetic nervous system. Point 3 is the period of compensatory relaxation after the stress has passed. This corresponds to the firing of the parasympathetic nervous system. Point 4 is the return to baseline.

TF: So that’s the normal, healthy way of reacting to stress.

KP: Yes. The long-term kind is what gives us trouble. This is a kind of stress that doesn’t go away as easily as a turn on the freeway. Job stress, family stress, emotional conflicts. Money difficulties. All the vague but ever-present problems and worries.

TF: What George Sheehan calls “the full-court press of life.”

KP: That’s good, that’s it exactly. There’s no end point, no clear resolution to that kind of stress.

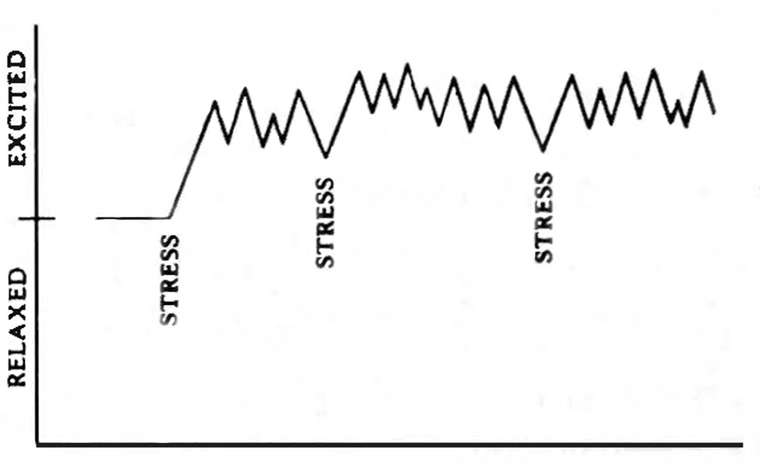

What happens physiologically is that all the bodily functions accelerate as though your life were in danger, and they stay elevated, without release. We experience it as anxiety, frustration, tension, and worry. If we were to hook someone in this kind of worry pattern up to a monitor, we’d see something like this:

They continue at a level of high excitation without the compensatory relaxation phase. This is the kind of biological stress pattern that leads to disease.

TF: So what would the yogi or meditator do in the same situation?

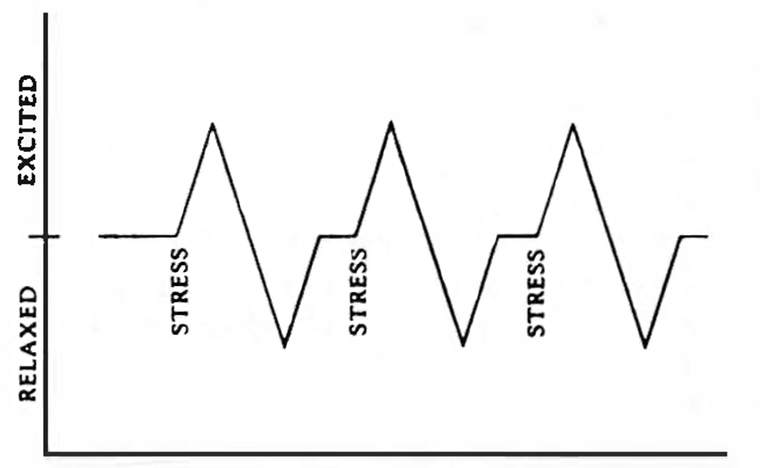

KP: What they’ve learned is to more clearly identify when the reaction is no longer necessary. They would experience the same stimuli as a series of discrete short-term stresses:

The striking thing about this pattern is that it looks almost exactly like the EKG tracing of a series of heartbeats. What’s missing in the chronic worry pattern is the parasympathetic rebound, the relaxation phase. What the yogis have learned to do is to induce this phase. To let go of those excess levels of self-stressing neurophysiological activity and simply quiet themselves down.

TF: They can intentionally produce the ‘Whew!’ phase of the short-term stress reaction.

KP: Yes. Then it is possible to come back to the baseline level and continue on. When we get into the chronic stress pattern it feels like there’s not going to be any end-point.

You can think of our bodies as being naive. They can’t tell if your life is really in danger or if you’re just thinking as if your life were in danger. The fear of losing your job might feel just as threatening as if a speeding truck were coming at you. You might react this way to a nagging creditor or to your income tax coming due. Whatever the cause, you go up above the line, and before you can come back down, the next stressor hits. A job deadline. A family problem. And you go right back up again.

TF: How long can that pattern go on?

KP: A long time! In someone with a real chronic stress pattern, the only thing that’s going to break the cycle is some kind of illness experience. You then see a very sharp drop:

This represents a state of complete nervous exhaustion, a nervous breakdown, a heart attack, a debilitating headache, an alcoholic binge — it can be any number of things.

TF: Everybody has their own favorite way to break the pattern.

KP: Exactly — and it’s very often illness, because when you’re sick there is a very different set of demands placed upon you. It’s now OK to stay in bed and just take it easy.

TF: So do you think that the way the Homes-Rahe Life Stress Scale (see page 13) works is that the items listed produce more frequent stress situations, making it more difficult to resolve each thing as it comes?

KP: Yes. As the quantity of change per unit of time increases, it demands more adaptability. Once you pass the limits of your adaptability, you go into the chronic stress pattern, that ‘just one thing after another’ feeling. It’s interesting to note that there are almost as many supposedly positive events on their scale as there are negative ones.

TF: How possible is it to predict who will get what diseases?

KP: I think it’s possible to some degree. The Friedman and Rosenman book (see page 13) and the Simontons’ book (see Resources) look at the relation between personality and heart disease and cancer, respectively. I’ve reviewed the relationships between these two diseases as well as migraine and arthritis in Mind as Healer.

TF: So people do have their own favorite illnesses.

KP: Oh, yes. The same stress level that might produce a headache in one person might produce a heart attack in another or gastrointestinal trouble in a third. Certain families, both genetically and behaviorally, will predispose to certain illnesses. Your environment will predispose you one way or another. So will your lifestyle.

TF: One thing that’s struck me about your work, Ken, is that a good many people with very similar interests have gotten interested in ways of working that have taken them a long way from the research lab or the traditional medical clinic. You’ve chosen to stay very close to the approaches and techniques of traditional research and clinical practice. Could you comment on that?

KP: One of the things I’ve been trying to do, almost insidiously, is to stay very conservative in my approach. The data is there, in the psychological research literature. You don’t have to go look at far-out things. You don’t have to guess, you don’t have to speculate. You don’t need to have far-out theories. This area is easily approached with the traditional tools.

So I’ve limited myself to citing from the Journal of the American Medical Association, Annals of Internal Medicine, Archives of General Psychiatry, or Science — which, by the way, has devoted an entire issue [May 26, 1978] to health maintenance and contains some of the best articles and most radical statements you will ever see on the need for a new way of looking at medical care.

I’ve tried to stay within the scientific medical tradition to see whether medicine really is incapable of dealing with these kinds of issues or whether there’s simply a huge body of literature that has been ignored.

By and large, it comes down to the fact that the information is there in the journals, and it’s been largely ignored and overlooked. This stuff is as compatible with medical practice as anything you can imagine — that’s what makes me so optimistic that this is a valid direction for medicine. We’re not trying to set up some wild alternative. In fact, it’s probably more consistent with the roots of medicine than the bio-medical fixation of the last thirty or forty years.

The most exciting thing about this work is that once you get people moving in the direction of health, they don’t want to stop at just being ‘normal.’ They keep going toward becoming much healthier than average.

TF: What are some of the ways to break the chronic stress pattern?

KP: I think the main ways are stress management, diet, and exercise. There seems to be a real synergistic effect among these three. If you start exercising, it breaks up both physical and mental tension. There’s a slide I use that shows all the supposed effects of drugs that lower blood pressure on one side and the effects of light exercise on the other. The physiological changes produced by exercise are comparable if not greater than those brought about by the drug.

TF: As any runner could tell you.

KP: Right! That’s the kind of thing that we, living in the Bay Area, have somehow picked up; but do you know that it’s never mentioned in the literature? It’s not taught in medical schools — and that’s really the status of most of this information. It’s there, but it’s not known. There are damn few doctors that will put a newly diagnosed hypertensive on a running program.

TF: Does exercise increase the ability of the body to deal with stress using the short-term pattern?

KP: Definitely. The better the shape you’re in, the better you can handle stress, and the less likely you are to get stuck in the chronic stress pattern.

TF: How does exercise have that effect?

KP: I think it works in two ways. First, it produces distinct biochemical changes — as a result of being more physically fit. That helps you cope with stress. Second, if you’re taking the time out of your life to go exercise, you’re taking a psychological stance that’s already going to have you reacting differently to your job, your office, your sense of achievement, your career.

The error comes in when you start interpreting relatively non-threatening situations . . . as though they were life-threatening.

Then you are creating the crisis in that life-event.

TF: Meyer Friedman and Barbara Brown both talk about a kind of conceptual shift that a person can undergo, so that afterward, things that were considered highly stressful are no longer perceived as so potentially perilous. Friedman mentions that a good proportion of post-heart-attack patients spontaneously go through such a shift after their heart attack. When he has asked them what kind of a process it was, they say something like, “I just looked at all the things that used to bug me, and I said to hell with it.”

KP: I hear that from patients all the time. That’s the kind of change we’re trying to learn to produce — how to help people learn to decide whether a given event is life-threatening or not. If it is a life-threatening event, you’d better be glad you’ve got all these psycho-biological mechanisms. If a car is coming at you, they give you the energy to jump out of the way.

TF: It’s a mistake then, to think that all stress is bad.

KP: Right. When a stimulus comes in, you perceive it at the cortical level. There are connections from the cortex to the hypothalamus to the pituitary. You’ve got relays going through the central nervous system as well as through the adrenocortical system. Both of these react. The error comes in when you start interpreting relatively non-threatening situations — like balancing your checkbook or dealing with a certain person — as though they were life-threatening. Then you are creating the crisis in that life-event. All the same responses take place as if a car was coming at you at eighty miles an hour.

TF: In my first clinical years of medical school, it was a real crisis for me when the chief of medicine came on the ward — because he loved to grill medical students. Then just last year, when I did my last student clerkship at San Francisco General, I noticed that when the chief of the service came on the ward, I was able to relate to him as just another person. In the interim I had gone through a conceptual shift; I’d come to see my role as a doctor as more than just being able to remember a lot of technical information. So I reacted to a very similar situation in a very different way. In the earlier situation, when the chief came on the ward, I could just feel my body going crazy.

KP: Yes, I think you can achieve that conceptual shift in any number of ways, one of which is the painful, involuntary way through severe illness that forces you to look at your values. That’s why I think illness can be a very creative experience — a potential source of regeneration and renewal instead of just a breakdown.

TF: Learning from illness — that was going to be one of the original sections of the magazine, but I never came across much of anything on the topic, other than John Perry’s work with psychosis as a healing process.

KP: Another person is George Engel, who is a professor of preventive medicine at the University of Rochester and really a very, very bright guy. He has written a series on people who experience severe life crises and then change their lives as a result. He just had a piece in Science, “The Need for a New Medical Model,” that references some of his earlier papers.

Severe illness, then, is one way to get that conceptual shift, or you can take a more preventive approach — become aware of the problem and make conscious changes.

TF: How about paying attention to early symptoms, before an illness gets to a serious stage?

KP: Definitely. There are usually many symptoms before the heart attack. The one thing you can count on is that if you ignore the symptoms, the body will up the ante. The next symptom will be more serious if the first is ignored, until finally, the body has nothing to do but give out.

Most people think the symptom is the illness. It’s not. The symptom is often very useful, telling you that you’ve pushed yourself beyond a level of healthy functioning. Too many people miss the early signals and get the opportunity to examine their lives — perhaps for the first time — at the cost of a serious illness.

TF: So people who get serious illnesses are the ones who are the least aware of the messages from their bodies?

KP: It’s not that they’re insensitive, it’s that they’re sensitive in the wrong way. The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory uses a comparison called a neurotic triad with three scales — hyponcondriasis, hysteria, and depression. When these three scales are simultaneously elevated, it indicates persons who are usually psychologically very intact, but have a lot of physical symptoms — those who attend to their bodies in a neurotic way. When they see a symptom, instead of saying, “That’s a symptom I need to change,” they say, “That’s a symptom I need to worry about.” This adds further anxiety, and gets them further into the chronic stress cycle. A healthier approach would be to say, “Aha. I see that symptom as a sign that I’ve been pushing myself past the limits of adaptability.” There is unfortunately a huge amount of fear associated with the discovery of a potential symptom, because people don’t feel they have any clear alternative of what to do. One of the things we did in a hospital in San Francisco was to teach biofeedback to patients in an intensive care cardiac unit. If a patient had an irregular heartbeat and didn’t know what to do about it, his anxiety over the symptom would make the arrhythmia even worse, until often digitalis would have to be prescribed. If the person had learned self-regulatory techniques to use when the arrhythmia began, he could have actually monitored his own heart rate and had a milder crisis experience as a result. It’s just like the situation you mentioned with the snarling dog. You can freak out and run and the dog will probably attack you, or you can stand your ground, stay relaxed, and, uh . . . relate to the dog.

TF: To get back to what people can do . . . what can people do?

KP: Aha. The big question! What can you do other than becoming ill? Well, I guess some kind of centering or meditation — in a very wide meaning of the term.

Any activity that you have in your life can be used as a meditation. It can be looking at a mandala, doing a mantra, sex, prayer, walking, running — it can be anything.

TF: Listening to Bach?

KP: Exactly. Any activity that you invest with prolonged and focused attention can be a form of meditation. Biofeedback is simply machine-assisted meditation.

TF: Would you say that meditation is a way of intentionally inducing this post-stress period of relaxation that brings you back to normal tension levels?

KP: Yes. The upswing is the sympathetic component. The dip, which corresponds to the S component of an EKG recording of a heartbeat, is the parasympathetic rebound. It’s a compensatory period of relaxation or deactivation that’s characteristic of every single nerve cell, every single muscle cell in the body. That cycle of up, down, and return to baseline almost exactly describes the electrical activity of the heart during one heartbeat. To me, this pattern is a source of real wisdom, because it gives us, with every beat of the heart, with the firing of every nerve cell in the body, a demonstration of the optimum response to the environment.

It’s all very consistent with the zen philosophy in which you perceive an event, react to it, and then let it go. The neurological pattern is a perfect correlate to this philosophical view, which I think is really fascinating.

TF: Really.

(Laughter.)

KP: It’s nice when so many things start coming together. Everything in this kind of work keeps coming back to some idea of individual . . . I don’t know quite what to call it — ‘responsibility’ is laden with so many unfortunate connotations.

TF: Self-care.

KP: Self-care! That’s it. It’s just paying attention to a beneficial way of living your life so that your exchanges and interactions with other people are loving and caring, and your attitudes to your self are that way, too. The kind of meditation we’ve been talking about is a fine way to come at it — although people come to it by very different roads. For some people, paying attention to nutrition leads to paying attention to other areas of their life. Others come at it through exercise. They realize that they can’t even run around the block if they’re feeling tense, and they get interested in meditation. Another person might start meditating and then realize, “Wow, I really don’t like that gut hanging over my belt.” Suddenly this person is into considerations of diet and weight. It’s really a very organic, unified process of discovery.

TF: Paying attention.

KP: Paying attention. Investing your life with attention. Was it Socrates who said, “The unexamined life is the unlived life,” or something like that?

TF: Yes — or Henry James, who said, “Try to be someone on whom nothing is lost.”

KP: Perfect. That’s it. Meditation, biofeedback, Jacobson’s relaxation methods, autogenic training — they all allow you to take a break from a cumulative, destructive cycle, and to induce the parasympathetic rebound with all its attendant slowing down and relaxing effects. On a psychological level, it’s taking that break, taking time to see why you’re involved in a particular phase of the rat race and whether you want to stay involved.

TF: How about the effects of eating on stress?

KP: All of the things we do to ourselves by eating a non-optimal diet make us more susceptible to specific disorders. When you sort through all the opinions about diet, you find there are a few widely agreed-upon guidelines — ones that almost everyone knows and few practice — that really can help a person be much more healthy. Decreasing intake of refined sugars, which are uniformly destructive. Decreasing fat consumption. Diversifying your protein base away from meat into non-meat sources of whole proteins, the kinds of combinations that are talked about in Diet for a Small Planet. Eating more fresh, less processed grains, fruits, and vegetables.

TF: What kinds of things about eating would be most useful for our readers to know?

KP: I’m working on a chapter on eating for my new book right now. It covers four phases. The first is to define, clearly, the basic vocabulary you need to approach anything from a research article to Adele Davis — what’s a vitamin, what’s a carbohydrate, what’s a protein.

The second phase is to identify the clearly agreed-upon destructive and constructive aspects of eating.

The third is to assess your present diet, using some computer assessment forms, to keep track of what you eat for a certain period. The computer calculates your weekly nutritional intake and makes some specific suggestions as to how you might alter your diet in a positive direction — increasing the consumption of folic acid, for example.

The fourth phase is to examine those biases and myths we all carry around that keep us from choosing an optimal diet.

TF: What about eating for emotional reasons? Paying attention not only to what you eat, but where and when and why you eat.

KP: Absolutely right. In fact, the most common problem I find in working with people who have a slight to extreme weight problem is they eat as a form of tranquilization. That sated, relaxed feeling you get after eating a large meal is something they seek again and again.

TF: If you’re getting that pleasant relaxed feeling from meditating or running several miles a day, it changes your perspective on food.

KP: It makes a total difference. Another thing, too — all these things should be fun. Too many people are so dour. They’re going to become healthy if it kills them. The person who drives himself to jog and hates it. The person who eats so austerely and with such a restricted diet that it’s really masochistic. The person who insists on meditating half an hour twice a day whether it really fits into their life or not.

TF: They’re equally not paying attention.

KP: Yes, because when you’re doing it right, there’s a spark, an element of vitality, of discovery, that makes it really exciting. You’ve got to follow the little messages from inside that tell you what’s right for you, no matter what any expert says. If that spark’s not there, you’re sunk, no matter what you do.

References

Engel, George L. “The Need for a New Model: A Challenge for Biomedicine.” Science 196 (8 April 1978): 129-136.

Lappé, Frances Moore. Diet for a Small Planet (Revised Edition), 1975, 411 pages, $1.95 from Ballantine Books, 201 East 50th Street, New York, New York 10022.

Perry, John W. “Reconstitutive Process in the Psychopathology of the Self.” Annals of the New York Academy of Science 96 (1962): 853-76.

Simonton, Carl O., Stephanie Matthews-Simonton, and James Creighton. Getting Well Again: A Step-by-Step Guide to Overcoming Cancer for Patients and Their Families, 1978, 268 pages. $8.95 from J.P. Tarcher, Inc., 9110 Sunset Blvd., Los Angeles, California 90069.