Four months into their seven-month tour, the mostly nineteen- and twenty-year-old marines at Patrol Base Fires in Sangin, Afghanistan, had seen enough violence to permanently line their boyish faces. Two of their platoon’s men had been killed by improvised explosive devices [IEDs], one of them blown literally in two. A half dozen had gone home without their legs, and others had suffered severe concussions or taken fragments of flying metal on their exposed faces and through the gaps in their Kevlar armor. By the time I arrived to photograph and interview them in July 2011, First Platoon’s casualty rate was more than 50 percent.

Lance Corporal John Bohlinger describes Sangin, a district of fourteen thousand in Helmand Province, as “a lot like Vietnam mixed with Kansas” — a firefight in a minefield, set against a backdrop of beanstalks and head-high corn, with low-slung khaki-colored mountains on the horizon. Sangin is a key way station along the narcotics- and weapons-smuggling routes on which the Taliban depend. The district is so remote, so cut off from the Afghan government, that none of the farmers with whom I spoke knew the name of their country’s president. They could not name Helmand’s provincial governor either, or even their district-council leader. They did not know what country the marines in their fields had come from, let alone why they were there. They did know that they were tired of living in a war zone. They were afraid of everyone, and that fear had driven hundreds of Sangin families to Kabul, where they were waiting out the war in filthy encampments on the city’s western outskirts.

The official stated mission of the U.S. troops in Afghanistan is to strengthen the Afghan security forces and local governance structures and to ensure a “secure environment for sustainable stability.” And yet here was a platoon of marines shedding an extraordinary amount of blood in a place where there was virtually no local governance, barely any Afghan police or army troops, and a population that wanted nothing more than to be left alone. The parallels between the marines’ mission in the backwater of Sangin and their forebears’ mission in the jungles and rice paddies of Vietnam were so obvious that First Platoon had dubbed the place “Vietstan.”

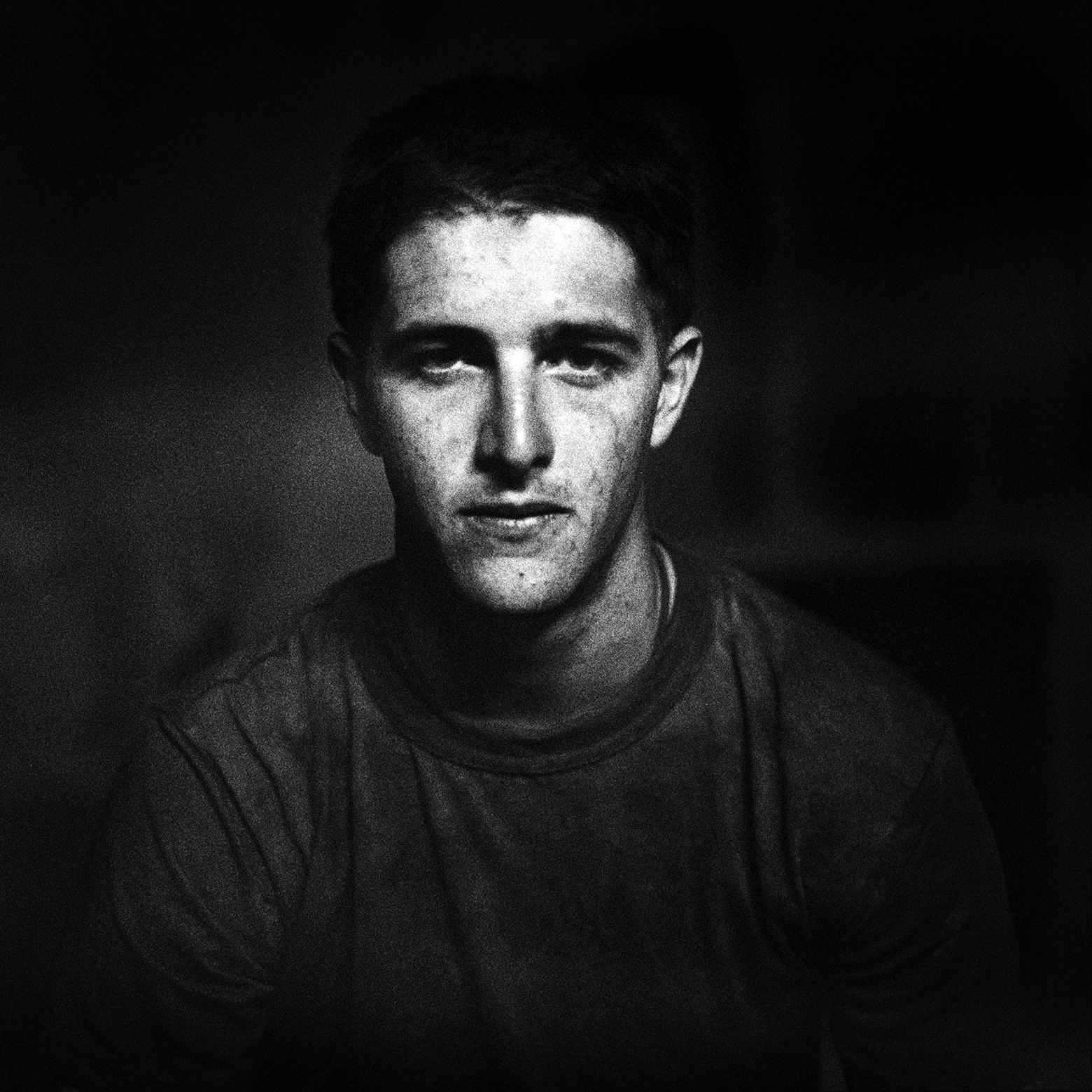

On June 12, 2011, the same day that the platoon’s minesweeper, Lance Corporal Joshua McDaniels, was blown in half, and IEDs claimed three marines’ legs and the company commander’s foot, nineteen-year-old Lance Corporal David Richvalsky took a dime-sized chunk of metal to his temple and so much shrapnel on the right side of his body that he looked, in his words, as if he “fell off a skateboard and slid for about ten feet.” His face, he said, was like “a nasty burger.” The IED blast shattered his eardrums and compressed his skull, leaving him severely concussed and nearly deaf. These injuries could have won him a trip home for good, but Richvalsky said he pushed to come back — not because he wanted revenge but because he couldn’t stand the idea of leaving his squad mates behind.

The portraits that follow — of the eleven marines in Third Squad, First Platoon, Bravo Company, First Battalion, Fifth Marines, and their navy field medic — reveal a side of the modern infantry that we don’t often see. We’re inundated with photographs of troops in full combat gear, as in half the portraits. Those images say something about the enemy threat level and the terrible firepower we bestow upon young soldiers, but they’re the stuff of recruitment posters, and they tell us little about the boys underneath all that armor. They tell us little about the brothers, sons, and husbands who were shooting spitballs in high-school classrooms a year and a half before; the young men who are deferring dreams of college and girls and fast cars to serve in a war that has largely been forgotten; the human beings who go to sleep in bedrolls infested with sand fleas, closing their eyes each night to visions of chewed-up limbs and buddies screaming in agony as their blood pours onto the Afghan dirt.

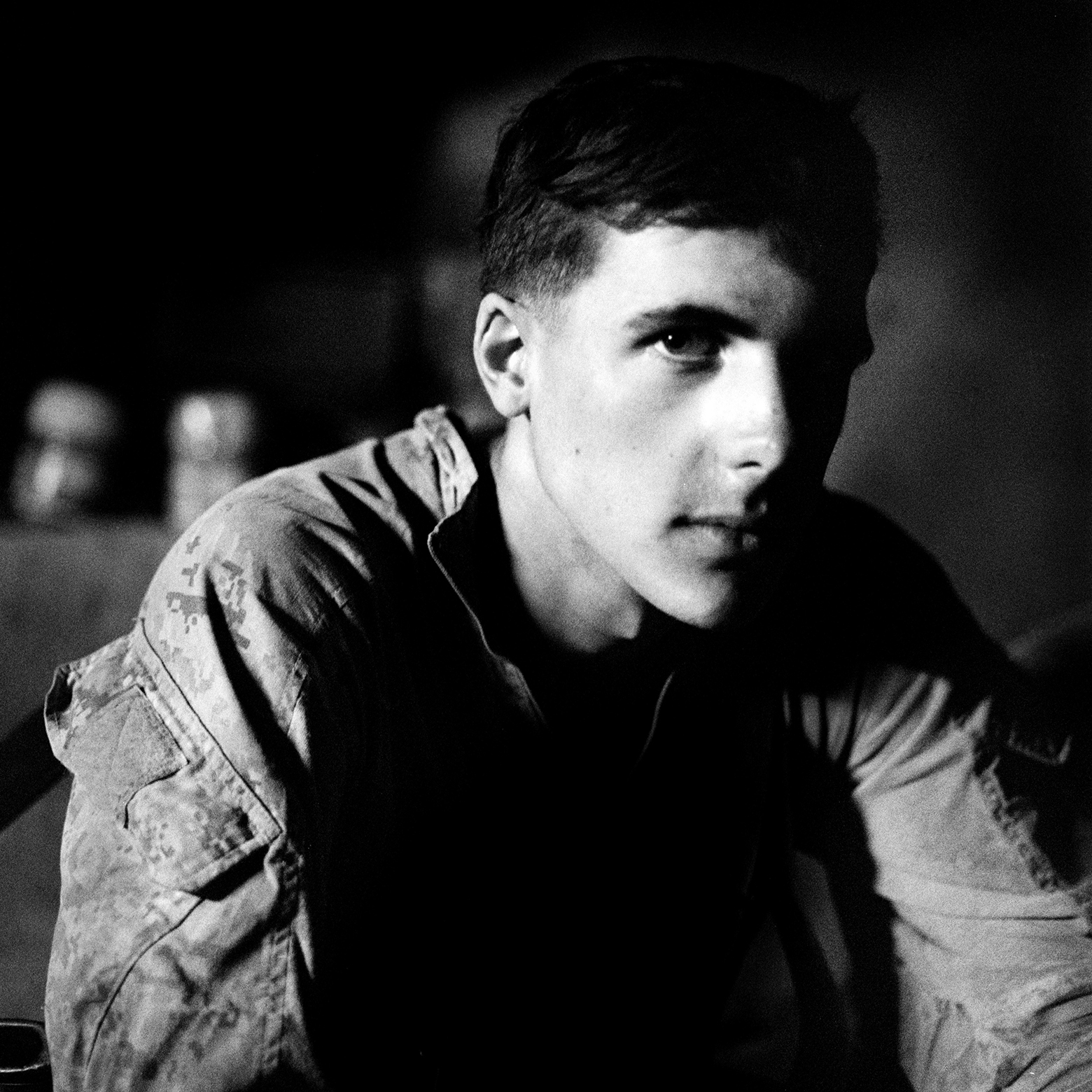

Corporal Michael Dutcher, pictured here, died on September 15, 2011, the victim of yet another IED blast. Dutcher, a soft-spoken twenty-two-year-old from Asheville, North Carolina, proudly sported his goofy standard-issue glasses and was engaged to be married when he returned from Sangin. He was unfailingly generous with his cigarettes and with the Frank’s RedHot sunflower seeds that he carried on patrol, stuffed between his sweat-soaked ribs and his body armor. “Dutch,” as his friends called him, had learned a few words of Pashto and seemed to enjoy making small talk with the farmers. He planned to get out of the Corps in 2012 and go to school, maybe become a special-education teacher like his mom.

“The thing I miss most about civilian life in general is definitely weekends,” he’d said to me. “I can’t wait to go back, sleep in, and not have to worry about anything.”

Dutch died with less than a month left of his tour. Now his squad mates are back at Camp Pendleton in California, where they’ll begin to file away the memories of fellow marines like him, of the laughter and sorrow they shared in a place beyond most Americans’ comprehension.

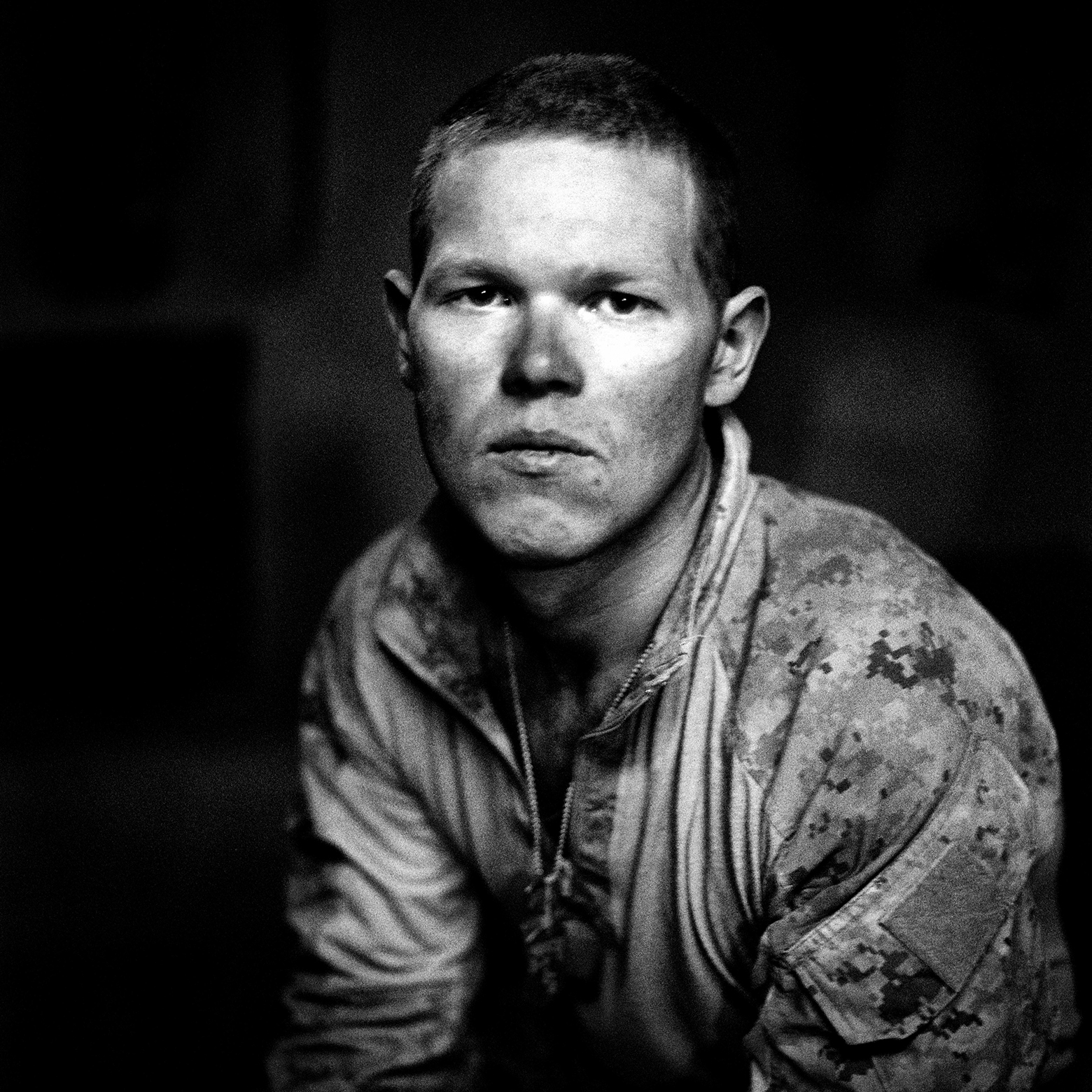

Lance Corporal John Richard “Bo” Bohlinger

Age twenty

Cheyenne, Wyoming

“In just over a month we lost over a third of our platoon. . . . At first it just fucking hurts. But then over time you get over it, and you start to get numb to everything. Someone gets hit, and it’s just someone getting hit. If they survive, they’re going back to the States. If they’re dead, at least they’re not here.”

Hospitalman Matthew Thomas “Doc” Foreit

Age twenty-five

Stone Park, Illinois

“My first casualty, when I got to him, his legs were gone . . . at least, the flesh around his legs was pretty much gone all the way up to his waist. . . . Most of my time was spent just trying to get the bleeding stopped. . . . He still had a pulse when we got him on the bird. . . . I don’t know if it was in midflight or right when they landed that he died. But he was alive when we got him on the bird.”

Sergeant Jarick Fry

Age twenty-four

Irwin, Pennsylvania

“The billet of squad leader carries a lot of weight. Even when you get tired or lazy and the patrols keep dragging on, you have to keep your head in the game, and if you don’t, if one of them loses their life, it falls on your shoulders. I may be twenty-four in age, but the Marine Corps makes you age probably four times as fast mentally.”

Lance Corporal Jeffrey Lopez

Age twenty-two

Ventnor City, New Jersey

“I probably won’t tell my friends back home anything . . . ’cause they didn’t live through it, so I don’t feel they should know. They’re not gonna understand if I say, ‘Oh, our boy got blown up. He was missing both his legs. He died right in front of us.’ It’s just adding pictures in their heads that they shouldn’t even have. It sucks that we have them in our heads already. McDaniels, he was our engineer. I remember just sitting there, watching him look at us, just barely gasping for air. His head in my hands as I’m sitting there trying to talk to him, and he couldn’t even talk back.”

Private First Class Scott McEtchin

Age twenty

Pleasanton, California

“It’s important for civilians to hear stories from veterans of war zones — especially the sick, disturbing stories — because a lot of veterans don’t want to share that, and so the civilian world never understands. . . . It’s not like the fucking movies.”

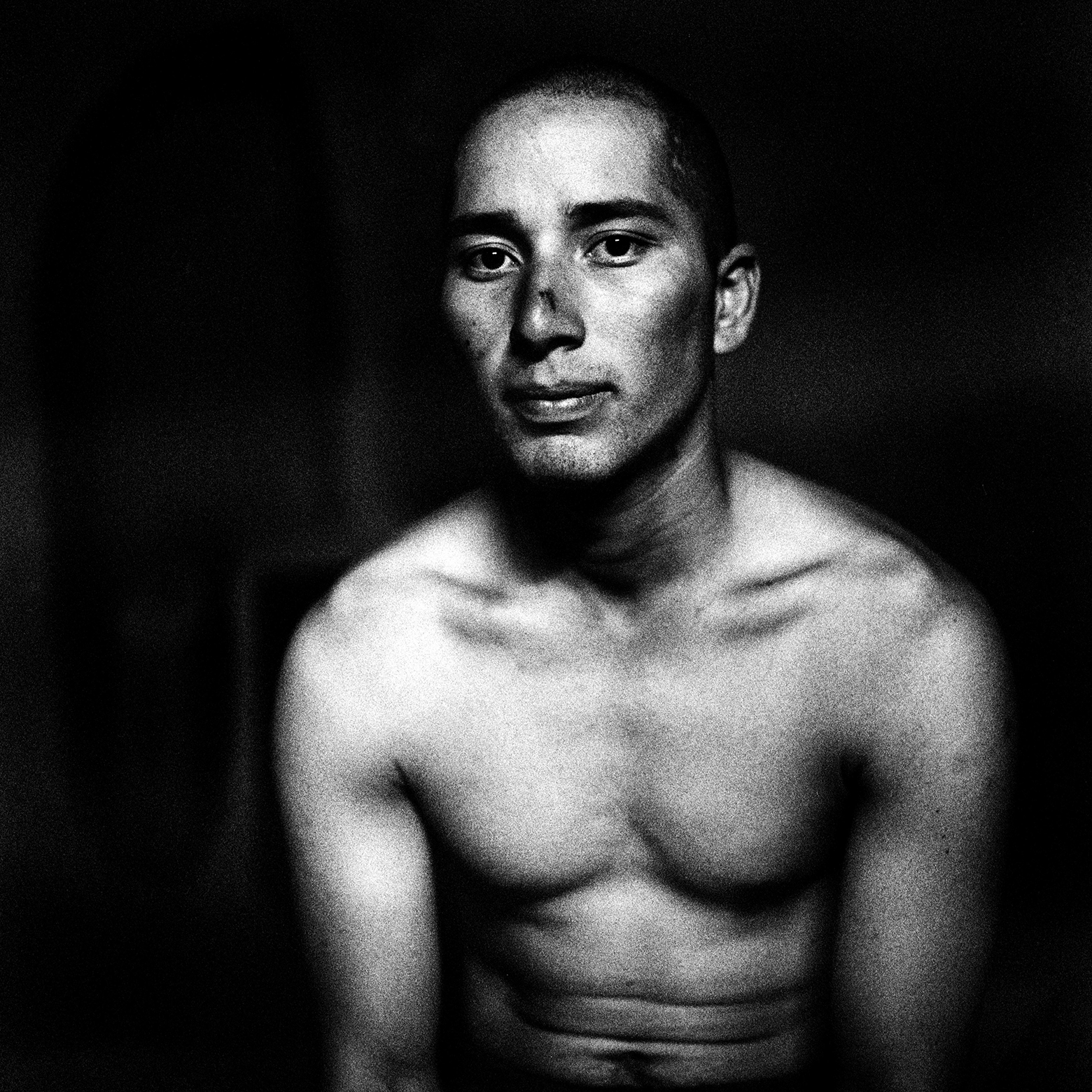

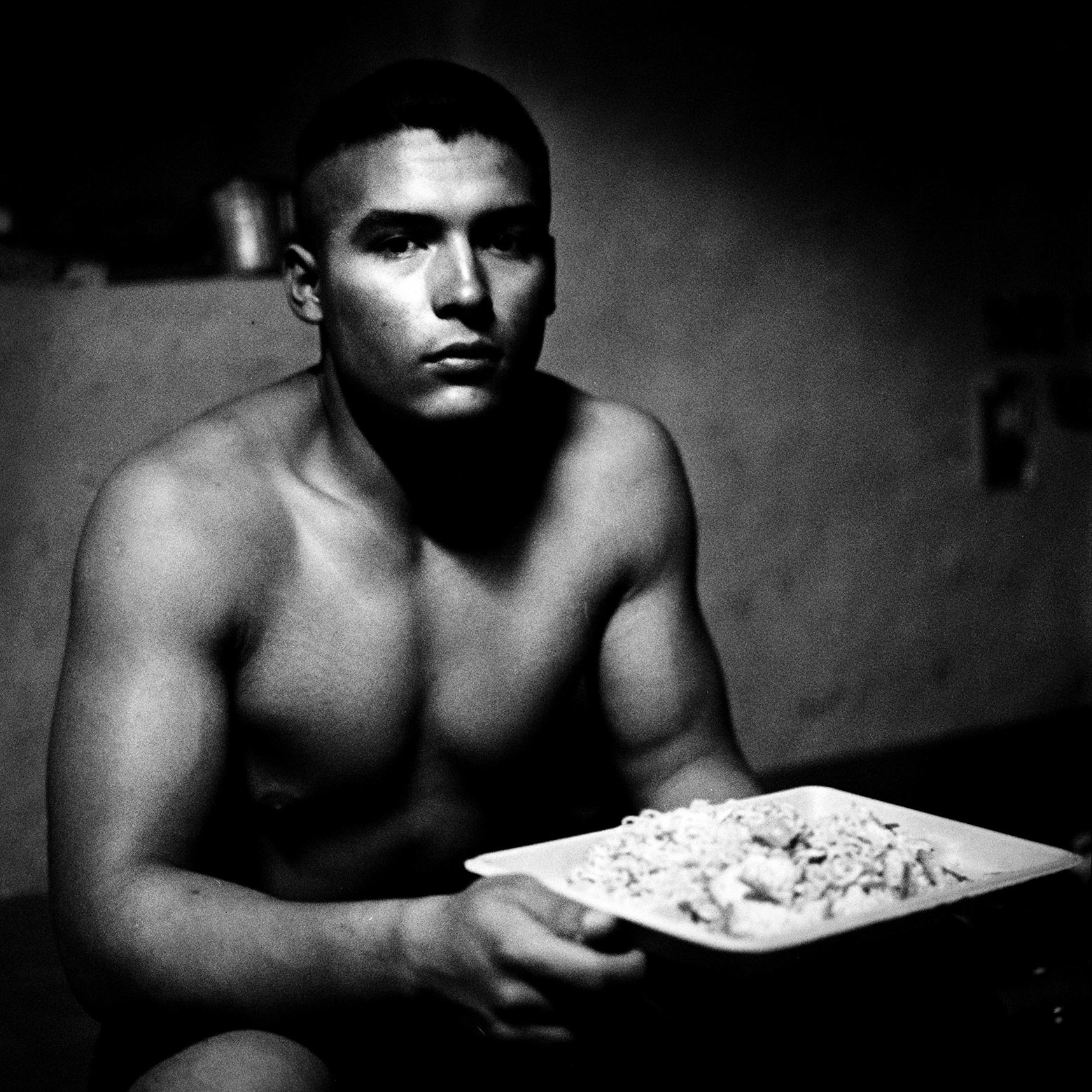

Corporal Manuel “Dozer” Mendoza

Age twenty

Weslaco, Texas

“I like to be up front on patrol. Honestly it’s kind of reckless, but I like to be up front because most likely I’ll be the one to step on a pressure plate, and nobody else behind me will step on one. . . . June 12 was when we struck the IEDs. Multiple IEDs. Worst day of my life. I knew from then on that I had to be careful. I had to think about my marines. . . . That was the first day my whole team was in front of me, and the one day that I let them walk in front of me is the one day that we run into an IED.”

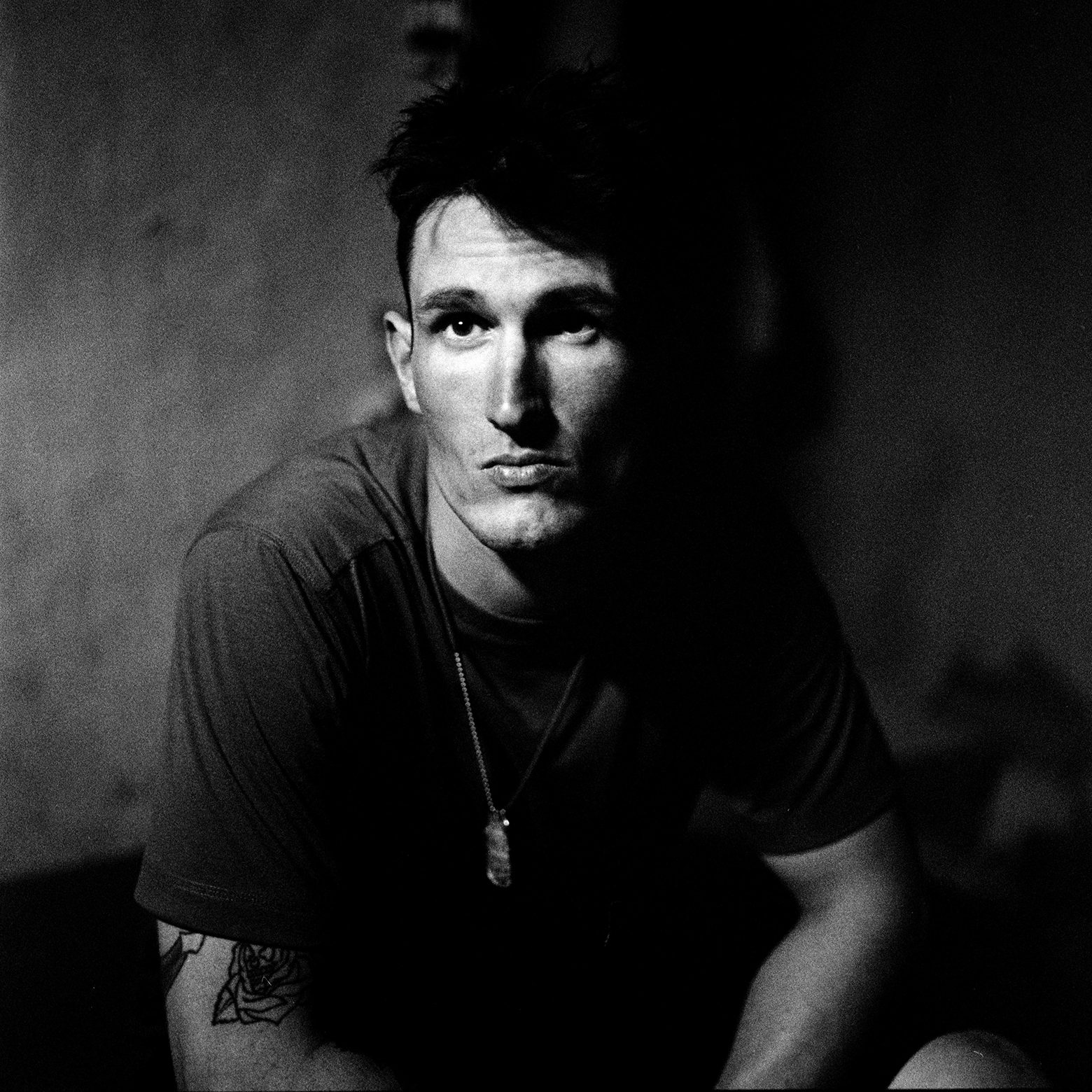

Corporal Michael Minor

Age twenty-five

Seagrove, North Carolina

“I was in Iraq three times and here one time. So I came to this already knowing what to expect. These guys had no fucking idea. When we took our mass casualties, I had to control everybody and try to calm them down, be like, ‘Look, it’s all right. Don’t worry. I’ve seen this before. You don’t see me overreacting.’ . . . Some of my old seniors used to tell me, ‘Get close but not too close.’ That way you have no emotional attachments to anybody around. ’Cause you never know when their time is. So I’m gonna have to come off as a coldhearted motherfucker. . . . It’ll definitely hit me at some point, but right now my job is worrying about them.”

Lance Corporal Taylor “Gecko” Moody

Age twenty

Watertown, New York

“I imagine losing my legs or an arm all the time. I could just imagine going back to Germany and getting surgery, and then I’m all healed up, and I get my little ‘tink-tink legs‚’ is what we call them — our little metal legs. We make jokes like ‘I think swimming would be so much easier. We just attach paddles to our little metal legs.’ It’s all about making jokes out here. If you don’t make jokes, it’s just too grim.”

Lance Corporal David Ortega

Age twenty

Beaumont, California

“I knew what I was doing when I went to go talk to the recruiter, because it was a time of war, and I knew I was gonna get sent out here. But just being in this situation, it’s kind of shocking. . . . The Taliban fighters, they’re not stupid. A lot of people say they’re stupid, but they’re good at what they do. They observe us. They watch our routes, and they watch everything that we do for a while, and then they hit us with IEDs on routes that we take or tree lines that we take constantly, and they have complex ambushes.”

Lance Corporal Brian Shearer

Age twenty

Rapid City, South Dakota

“None of us guys have seen our families in almost a year now. I’m really looking forward to getting back home, being able to just relax with the family, and just not having to worry on a day-to-day basis, ‘Am I going to lose my legs today or die today?’ That’s probably one of the biggest things I miss about being a civilian, is just the sense of security you have.”

Corporal Michael Joseph “Dutch” Dutcher

Age twenty-two, deceased

Asheville, North Carolina

“Since I’ve joined the Marine Corps, I’ve decided I want to follow in my mom’s footsteps and become a teacher. Right now I’m just trying to figure out what subject I want to teach. I might be an autism specialist like my mom or teach science or history.”

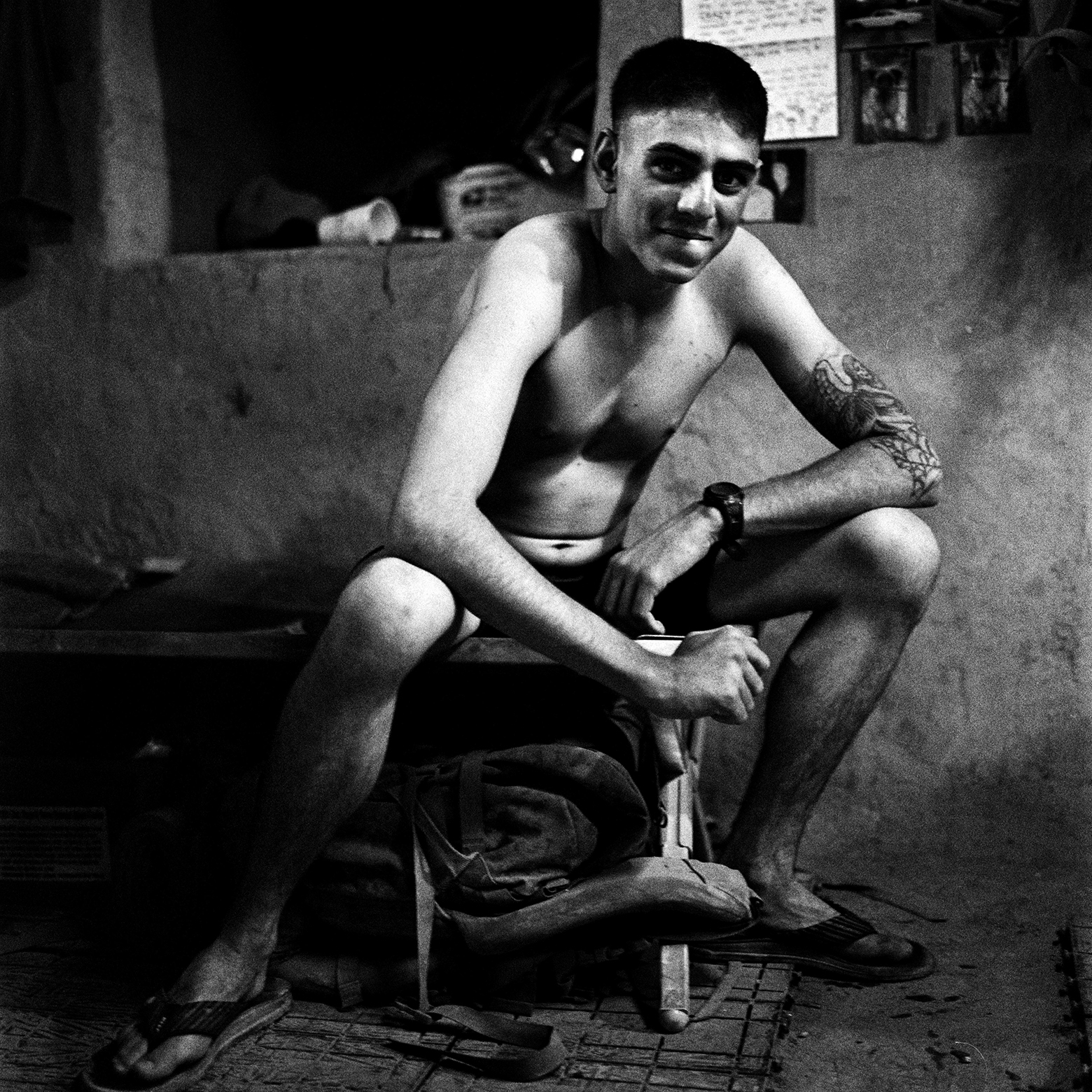

Lance Corporal David James Richvalsky

Age nineteen

Waialua, Hawaii

“I’m sure if I was fucking born in Afghanistan, I’d probably be Taliban, you know? That’s their deal; this is my deal. . . . I came back after I was wounded because of these guys, the guys that I’m out here with. This really isn’t my fight. This really isn’t America’s fight either. We’re kind of just here. . . . It’s only because I still got boys out here that I wanted to come back.”