SATURDAY

I write this at my parents’ home in Brooklyn as Hurricane Irene is approaching. Citizens are flocking to stores, buying out shelves of food. The mayor and the governor are issuing stern warnings. The television is talking nonstop, calling it a “monster storm,” measuring its winds at 105 miles per hour. This may be the “Storm of the Century.”

How ironic that the hurricane’s name is Irene, derived from the Greek word for “peace” — though in another sense it’s logical: the eye of a hurricane has an otherworldly peace, as does a disaster’s aftermath. You climb out of your storm cellar and examine your half-million-dollar home, now reduced to splinters, and you remember the poem by Mizuta Masahide:

Now that my hut has burned down, I have a better view of the moon.

Then you sit on the ground, fold your hands, and wait for the FEMA representative.

Earlier today, after lunch with my parents, I walked in Prospect Park. The day was sunny yet cool — perfect August weather. Watching joggers, bicyclists, and speed walkers, I thought of recent disasters: Hurricane Katrina, the Indian Ocean tsunami, the earthquake in Haiti. Before each of these horrors, perhaps, was a balmy afternoon like this one, a day everyone lived as if it were sweetly eternal. Once I saw a movie about the war in Iraq that showed children on swings in a Baghdad playground the day before the American attack. It was painful to watch innocent childhoods about to be shattered.

Meanwhile on TV people are being evacuated from seaside houses; newscasters are tense and voluble. In the 1970s Hollywood made disaster movies like The Towering Inferno so that we could experience vicariously the exquisite pleasures of destruction. Now the TV news has learned to narrate “reality disasters” starring you and me. Most of these catastrophes are bogus, but no one minds. They keep us entertained — wondering if, perhaps even hoping, we’ll be the next victim.

At 5 PM, as the hurricane was nearing, my wife, Violet, and I took another walk in the park. There was no rain yet, just a glowering sky. We met a man sitting on a bench with a small blond boy. The man had just been speaking to some Italian tourists. “Have a good hurricane!” he called to them gaily.

“That’s the perfect farewell,” I said to him.

He smiled. He was in his fifties with mutton-chop sideburns. “Isn’t it wonderfully still?” he asked. “The birds are all in hiding.” I listened; he was right. The stranger gestured to the sky above us. “You can see how the clouds are moving in an arc. That’s the very edge of the hurricane.”

Looking up, we saw the spiral of dark clouds against the slate-gray sky.

His name was Joshua, he said, and he was a geography professor. His father had been a Jewish union organizer, like mine. Joshua and I exchanged looks. Sons of organizers know that in the 1930s you could be attacked, or even killed, for organizing a fifteen-minute coffee break.

Who else would be out in a hurricane but the progeny of fearless CIO heroes?

Violet and I returned to my parents’ home, and I began storing water. I filled four plastic containers — the kind Chinese restaurants deliver soup in. I emptied one of my parents’ pretzel jars and filled that too. Also the teakettle. Meanwhile my wife filled the bathtub. I meditated, then slept.

SUNDAY

In the morning a lot of trees are down. A silver maple has fallen into an empty parking space right next to our car.

My parents turn on the TV. The hurricane has mostly spared the city. Only one person has died, out of eight million. But upstate New York, where Violet and I live, has been hit hard.

Violet calls our friend Mark, who says that our neighbors Robert and Holly have water right up to their doorstep. Our house is six feet lower than Robert and Holly’s! Plus it’s a double-wide trailer. Quite possibly it has been wrecked forever.

Lately I’ve had a fantasy of moving to Moscow with my wife. Perhaps now I’ll see it fulfilled. Violet has a degree from Dartmouth in Russian and could get a job as a translator. I could walk around bemused, like I do everywhere.

MONDAY

Violet and I drive back home to Phoenicia. Two miles away, in Mount Tremper, we pass four houses that have been wracked by the flood. We see a woman and two children walking out of one of them, looking stunned. Their lawn is gleaming mud. The house is dark like a cave.

When we arrive at our home, it appears unharmed. I enter barefoot and feel moisture in the foyer. The waters of the raging Esopus River have left their mark on the tiles of our vestibule, but they politely ventured no farther. The welcome mat is completely drenched.

The garage, however, looks like an avant-garde art installation in which a room is covered with chocolate. Books, cushions, planks of wood, and jars of herbal tinctures are strewn on the floor beneath three inches of mud. Only the higher shelves were spared.

Next door, Buddy and Betty are contemplating their trailer. “Obama was here last night, standing on the bridge,” Buddy says. “He flew in by helicopter. If I was there, I would’ve thrown him in the river!”

“I hear they’ve declared this a disaster area,” I say.

“That and ten dollars will buy you a sandwich and a fucking soda,” Buddy replies. “Pardon my language.”

He says the electricity will be out for a week to ten days.

I walk through my miraculously undestroyed home, a little disappointed. I was hoping to move to Moscow.

My guru says that you should not thank God when you are saved from destruction. God has nothing to do with it; it’s just your karma. So I meticulously avoid thanking God.

Violet and I were victims of a previous flood, in 2005. Leo Tolstoy said: “All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” Similarly every sunny day is the same, but each flood is unique.

In the waning hours of sunlight I do yoga in our meditation room. I am in the cobra position when my wife appears with two fish. “They’re trout!” she exclaims. “I found them in the garage.” They are about four inches long, both dead.

After my yoga I sit on the living-room couch. Two candles flicker in the dining room. Outside the window is total blackness. (Usually we see the lights of Phoenicia.) I watch the flames of the candles dance. How peaceful is rural life! I can’t believe that every night I distract myself with stupid amusements on the goddamn computer. Once the electricity returns, I will train myself to turn it off. A disaster is a form of rehab.

Outside, the Esopus thunders like a three-hundred-foot-high tractor.

TUESDAY

There’s a fetid, fishy smell in our house. The front lawn is plastered with red-brown dirt. Our propane tanks have been knocked over like bowling pins, so we can’t cook. And the heating ducts in the crawl space under our house are filled with muck.

“Don’t leave any trash outside,” Buddy warned me this morning. “There’s been a black bear around — a big black bear!”

The bear is taking advantage of our temporary confusion to forage in our yards. Animals have an eye for weakness. They realize that we are helpless now, like a limping deer.

But already reconstruction is taking place. A snowplow has pushed away huge piles of silt that the Esopus deposited on High Street. The Preservers of Order are mobilizing!

Our friends Tommy and Janet invite us over for tacos and cosmopolitans (cocktails of cranberry juice and vodka). When we arrive, Tommy is on his hands and knees, wearing rubber gloves. One of their oil lanterns exploded a moment ago. “Maybe we had the flame too high,” Janet says.

The flood is teaching us about old technologies, which are trickier than electric lights.

The tacos are delightful, but with no lettuce. Everyone’s food is spoiling without electricity. It’s nice to have dinner with friends. We rarely do so, because normally we can make our own dinner.

Walking home, Violet and I look up at the stars, grown more numerous now that the lights of Phoenicia are extinguished. Our hamlet looks as it must have in 1923, before power lines reached it.

Inside, with nothing else to do, I sit on the couch and recollect the day. In The Stranger, Albert Camus says that you can spend a year in prison remembering just one day in the outside world. Similarly a half-hour of conversation can supply a whole evening’s reverie.

WEDNESDAY

We go to Monica and Chris’s house to cook and use the telephone. Our friend Anique arrives, saying they are closing her street because it may blow up. The propane tank from Sweet Sue’s Restaurant is in the river and could possibly explode.

“How exciting!” Violet says.

“Too exciting!” replies Anique.

Violet drives us home, and I do my yoga and meditation. As I am reciting my daily oaths, I hear a loud knock on the door. On the stoop are two firemen.

“We’re just checking to see that everyone is all right,” says the one holding a clipboard.

“I’m fine,” I reply. “The river came inside the door, then stopped. But our garage and crawl space are pretty wrecked.”

I ask where they are from, and they say Seneca County, up by Syracuse and Rochester. I thank them for coming to help us and ask about the propane tank on lower High Street. Could it really blow up?

“Well, it’s possible,” one says, “but you would need just the right pressure, and just the right flame. With my luck it would happen, though.” He reveals that he was in the river when they found the tank.

These two guys in my doorway are actual heroes.

“Well, thanks again,” I say.

“The fire station has dry ice,” the talkative one says by way of farewell.

Violet gets dry ice from a passing pickup truck. “Don’t touch it with your bare hand,” she instructs me. I remember that dry ice can pull off your skin. The substance is in a white bag, which we put in our freezer. It will last seventy-two hours, Violet says.

The fishy smell is dissipating. By inhabiting the house — opening windows and doors and sweeping the floor — we have saved it from decay. If this house stood alone for three weeks, it would become derelict.

The mud from the flood has turned to dirt on the roads. Each time a car drives by, it raises a cloud of dust. I am breathing the dried-out river.

THURSDAY

The dry ice lasted only eighteen hours, then evaporated. We are left with a bag of nothing.

The song “No Woman, No Cry” has been playing in my mind all day. How reassuring to hear Bob Marley sing, “Everything’s gonna be all right,” over and over.

You save money during a disaster. All the stores are closed, so there’s nothing to buy. Your friends give you free food, because it was about to spoil anyway. You get dry ice from the firemen. It’s a cashless economy.

The repairmen come to fix our propane tanks and restore the flow of gas. One thoughtfully removes his shoes when he enters our house, so as not to track in mud. I quiz him on the devastation. He says Prattsville is the worst, then Windham, then Arkville, then Margaretville.

Bob comes over and offers us hot showers at his house. (He has a generator.) “We’re national news!” he says.

I wonder if Christians from Arkansas will arrive to hand out cookies.

FRIDAY

Today Violet attends a meeting at Mama’s Boy Market, organizing volunteers to assist flood victims. “If you want to help, turn to the person next to you and ask if they need help,” the speaker suggests. The woman next to Violet asks, and Violet says yes. Within a half-hour four volunteers — all women — are at our house, collectively pushing the mud out of our garage with shovels, brooms, a hose, and a wheelbarrow.

As we work, I wonder whether the floodwaters attacked all at once or slowly. Boxes from one end of the room were tossed to the other end. The flood seemed violent, yet it dropped a pile of dishes without breaking a single one.

While we work, a lineman is fixing the power lines near our house. He climbs down and waves to us: “You’ve got power!”

Across the street the elm leaves start falling. Melancholy autumn is here.

SATURDAY

Five local volunteers appear at our house to haul away all our muddy possessions. Mr. Downs, who was my daughter’s fifth-grade teacher many years ago, is about to throw a dirty faux-velvet box onto the truck when he opens it to find a silver cup with the Hebrew word shabat (“Sabbath”) on it. He looks at me questioningly, and I retrieve the sacred vessel — perhaps given to my daughter at her bat mitzvah.

Four women and five men, in two days, have saved our garage.

SUNDAY

Our tap water is still full of silt. When you draw a bath, it looks as if an extremely dirty person has already bathed in it. We boil all our drinking water. But perhaps boiling is not enough. Could we still get cholera? I’ve asked many people, and no one knows. This morning our friend Bob comes over, and I mention that we might need water to drink. He soon returns with twenty-four bottles of Nirvana Positively Pure Natural Spring Water. An hour later he delivers a second case. Two hours later a fireman drops off a third, plus thirty-two bottles of Nestlé water. Suddenly, at no expense, we have 104 bottles of water.

The scriptures were correct: by losing our possessions, we have attained nirvana. Yes, the flood damaged our garage, but the garage was filled with worthless stuff. Every few weeks I would say to my wife, “We have to go through the garage and cull that crap. It’s driving me crazy!” Violet would nod her head, but this project would never begin. Now the merciful river has come to our aid.

Ultimately the flood occurred because the world is heating up, causing more water to evaporate, which makes more rain fall, often violently and erratically. All of industrial civilization is conspiring to pour water into our garage.

MONDAY

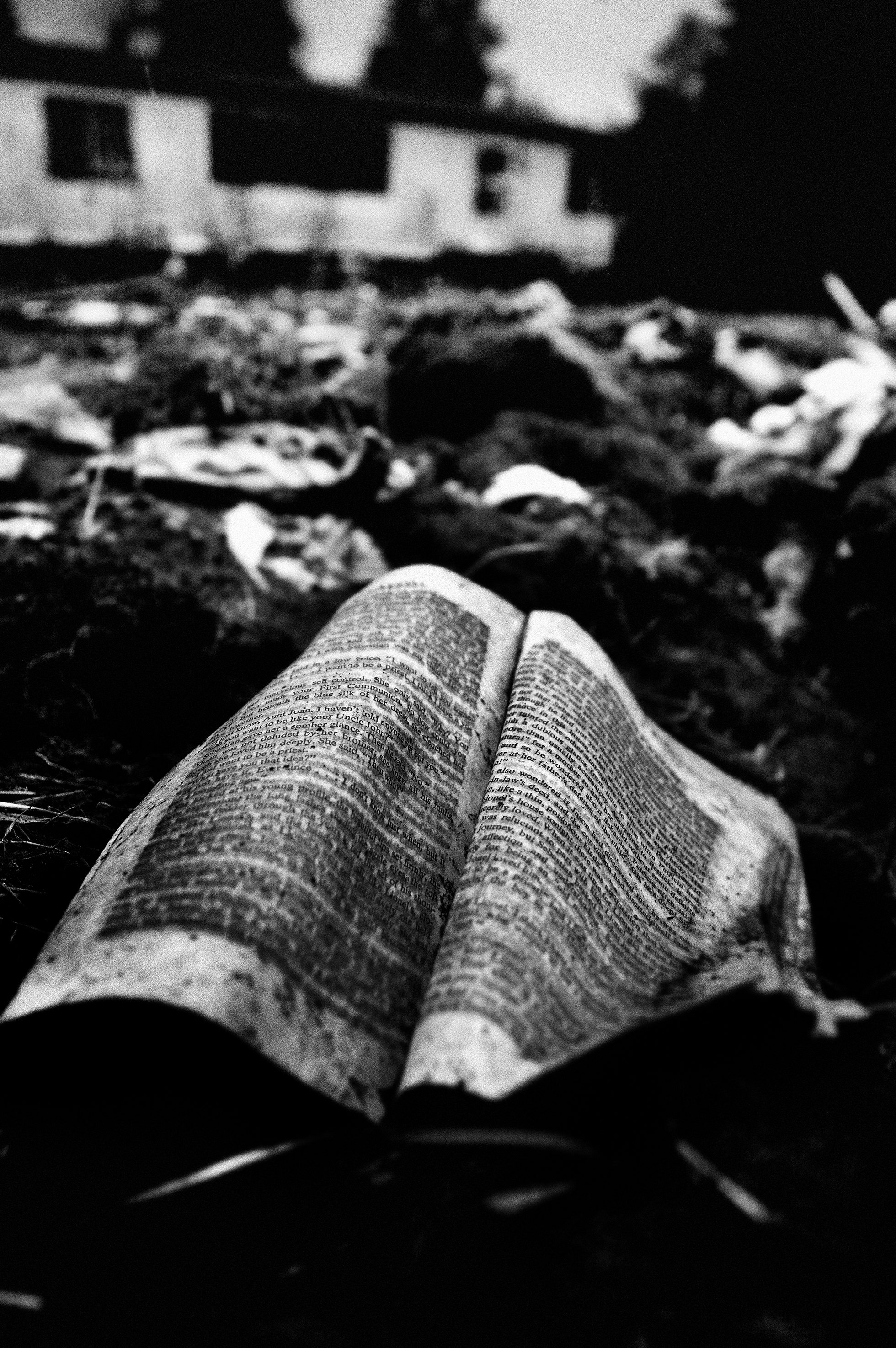

I’m practicing my new hobby: drying out books. So far I’m making fast progress, thanks to the sun’s healing rays.

When we reorganized the garage after the flood of 2005, I put my most precious volumes higher up, so most of the books that got wet were ones I didn’t much care for anyway. And almost all of them were free.

It seems horribly wrong, however, that e.e. cummings’s 100 Selected Poems is soaked. I read it just last month. I don’t mind my old books getting ruined, but this seems personal.

Our neighbor Nick returns our mailbox, which was swept onto his land.

TUESDAY

A flood consists of two elements: water and soil. Once you evaporate the water, the soil turns to dust and blows away. It’s quite simple, but, like all virtuous activities, it requires patience.

Today it’s time to dry out the record albums. (We still have a record player.) I begin with my daughter’s, some of which belonged to my parents and have entertained three generations: Handful of Keys by Fats Waller and His Rhythm, the original Oklahoma! cast album, Pete Seeger’s I Can See a New Day.

A gray stain has appeared on one of the garage walls: mold! It looks like a faint, abstract watercolor painting. Violet uses bleach, water, and a sponge to remove it.

There is a word meaning “before the flood”: antediluvian. I first heard this elegant term in the song “Atlantis,” by Donovan, in 1968.

It’s difficult to remember, right now, my antediluvian life.

MONDAY

If our flood were slightly larger, we would get visited by celebrities, but so far we’ve had none. Not even Susan Sarandon.

Today’s no good for drying out novels or album covers — a light rain is falling. I take a tape measure out to the garage to measure the high-water mark: 25 1/2 inches.

According to a newspaper, Hurricane Irene will cost $1.5 billion. I’ll probably personally have to pay about $2,200 of that.

A woman in a FEMA T-shirt arrives and hands out flyers telling us how to register for disaster relief, but Violet registered us last night, online. Each person gets his or her own private disaster-registration number. Ours is 38-1986037.

I never used to use the dishwasher, but with my current fear of cholera I have relented. (The appliance washes dishes in much hotter water than I can.) I normally disdain bottled water, but now I drink it all day. The flood has altered my moral code.

I write a letter to the Woodstock Times:

Dear Editor:

Ever since I was the (slight) victim of flooding (just my garage and crawl space), generous friends and near-friends have been assisting me and my wife. Four women tackled our garage mud on Friday, then five men appeared on Saturday to haul off our muddy Philip K. Dick novels and Genesis cassettes in pickup trucks. Since then, someone lent us a water vacuum, and the Red Cross has been bombarding us with chocolate-chip granola bars, packages of Cheez-Its, Red Delicious apples, and, today, a Mickey Mouse doll. Truly, Buddha was correct when he said that we are all encircled by kindness.

Sparrow

TUESDAY

My wife went to Higley’s Market. Al Higley was giving away lots of gourmet cheese, which was going bad from lack of electricity: Madrigal cheese, rosemary Harpersfield cheese, garlic-and-herbs goat cheese, goat cheese with horseradish. So we have an unexpected feast, thanks to Irene.

“The green beans loved the flood,” my wife says. “They’ve been growing like mad.” The rest of the garden got wiped out, but the green beans climb high and laugh.

WEDNESDAY

My wife woke me at 6:01 AM. “The firemen just came to our door and told us to evacuate!” she said.

The river is rising as the water from recent rains pours down from the mountains. It took me a while to understand. For me 6:01 AM is the middle of the night; I think like a four-year-old at that hour.

Now I’m in the state-owned Belleayre Ski Center, seventeen miles west of my house. My new home is a cot in a ski lodge. As I make my bed, a man on the cot behind me farts. Welcome to the evacuation center, his fart says.

At least the lodge is heated. (We still have no heat at home.) I close my eyes but can’t sleep. Women are standing near the picnic tables in the center of the room, conversing. Also, light comes in the windows. And my cot is not entirely cushy. It’s hard to relax in a shelter.

The last few days I have been singing to myself an old folk song:

The water is wide, I can’t get over; Neither have I the wings to fly. Give me a boat that will carry two, And I will go, my love and I.

I wish I knew the name of this song. At the moment I can’t get on the Internet.

I just realized: I am an evacuee. I could be a blurry face on a national news report: “Makeshift shelters were set up in ski lodges and churches.”

I love the term evacuee.

Children run by yelling. One has a bottle of water, which he is using as a gun. Children will play anywhere. They are probably relieved to be missing the first day of school.

It is surreal to live in a ski chalet, even one that is state run. Outside the window, the base of the ski lift is sheathed in a delicate mist. I listen in on the conversations of my fellow evacuees, most of whom were totally wiped out by the flood. A number of them live in trailers like us. Trailers are commonly placed in harm’s way.

Even natural disasters more often hurt the poor. Rich people tend to live higher up, on isolated mountaintops where they don’t have annoying neighbors asking them for help.

My wife and I probably aren’t real flood victims. Almost certainly our house will survive, as it survived last week, when there was a hurricane and not just three days of rain. (I’ve learned that the name of this rain is Tropical Storm Lee.) But we don’t know for sure. There is a small chance that we are real flood victims. We wait to know the answer, but no one with a walkie-talkie tells us anything.

At the cafeteria downstairs I get a grilled cheese sandwich for free from the Red Cross. Excellent!

How do evacuees have sex? Do they sneak into the women’s bathroom late at night?

THURSDAY

The danger has passed, and our home is untouched.

The town has finally officially encouraged the boiling of tap water. It’s quite possible that septic systems have overflowed and polluted our drinking water. It is frightening to think that you might be sipping someone’s shit.

Meanwhile the stain has returned to our garage wall — in fact, to all the walls. It is the Return of the Mold. “You’re going to have to cut out the sheetrock,” our friend Glenn, a contractor, tells us.

Sheetrock is basically two layers of paper filled with plaster. Once that paper gets wet, it never truly dries out. And mold can take over a house, rendering it uninhabitable.

TUESDAY

Excellent weather for drying books — hot, but not humid. Real August weather. A slight breeze flips the pages of Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego, by Sigmund Freud.

The Methodist church in Phoenicia is now filled with donated clothing and other items for us victimized locals. Everything is free, though there is a donation jar. My wife and I go there to sift through the piles of clothing and books. I consider taking Women Who Love Men Who Kill, a pop-psychology paperback about romantics who fall in love with convicted murderers, but I decide against it. I end up with two backpacks, four pairs of socks, and four pairs of pants, plus an orange hooded sweat shirt for my daughter.

It’s like a Walmart under socialism!

WEDNESDAY

“I called the town hall,” Violet says. “They say the water has been tested and is drinkable.” It still comes out of the faucet brown — though perhaps lighter brown than previously.

THURSDAY

Five workers rip out the bottom three feet of sheetrock in the garage. The mold penetrated even into the insulation, which looks like pink cotton candy sprinkled with tar.

Listening to the buzz saw chopping up the walls, I think: This is surgery. It’s like cutting the tumor out of a cancer patient. Hopefully we will stop the spread of this disease in time.

FRIDAY

My books are still drying, though a whole pile of them are done. And sometimes I find hopeless cases. Up, Up, and Oy Vey!, a study of the Jewish origins of American superheroes, has been overtaken by mold. I discard it. (It’s not very good, anyway.)

I can see why the young Jasper Johns burned all his paintings. It’s freeing. Your past is less of a burden. The future opens up.

SATURDAY

Violet and I go “shopping” again at the flood-victim clothing center. I return a pair of pants that didn’t fit and take three turtleneck shirts.

SUNDAY

It’s getting colder, and still we have no heat, due to the damaged ductwork. This morning it’s fifty-six degrees in our house. I’m sitting at the computer in a sweater, winter coat, and thick wool socks.

Later the sun warms the day. I take a hot bath and dress head to toe in disaster fashions: new clean socks, designer pants, and a black turtleneck. I look like a hip sociology professor circa 1961.

MONDAY

The bottled water has officially run out. Violet began drinking the tap water four days ago without boiling it, and she’s in stellar health. So I must be brave and drink water from the faucet.

TUESDAY

A disaster concentrates time, but now time is beginning to stretch out, to distend. All that remains is to find a heating company to install new ductwork under the house, hang new drywall in the garage, and insulate the crawl space.

The most discouraging thought is that a flood will probably come again. The only solution is to hike the house up on cinder blocks, but the cost is prohibitive.

Probably we can never sell this house, due to the danger of flooding, but we can rent it. Renters don’t care if their garage is flooded; they just wait for the landlord to fix the problem.

WEDNESDAY

I find a CD in my garage that I had forgotten: Eric Dolphy’s Last Date. The envelope is muddy, but the disc itself is clean. I place it in my CD player and hear Dolphy’s ingenious, acrobatic bass clarinet rise up, screaming with delight. No flood can destroy jazz.