In 1993 jazz musician Henry Robinett received a call asking if he was interested in teaching guitar to prison inmates. At the time his band, the Henry Robinett Group, had just released their second CD, and he had recently launched his own label, Nefertiti Records, but he was mostly a stay-at-home dad in Sacramento, California. He said yes because he needed the money and also because he was curious. He’d never been inside a prison.

Robinett began teaching twenty miles from Sacramento at the old Folsom State Prison, which had been built in the nineteenth century. The atmosphere was “intimidating,” he says, but the inmates were appreciative and put his mind at ease. He found that these men were not nearly as threatening and irredeemable as TV and movies had led him to believe. Since then, he’s taught off and on at numerous California prisons, including California State Prison, Sacramento — also known as the “new Folsom.”

Born in 1956, Robinett grew up in Sacramento. His father had a master’s in mathematics and business administration prior to World War II, and had been an instructor at Tuskegee Army Airfield in Alabama during the war. In 1964 Robinett’s mother, a social worker, took him with her to London, where they lived for a year and he was exposed to European culture, including the early days of the musical phenomenon known as the British Invasion. Back home in Sacramento, at the age of thirteen, he started playing guitar after hearing rock guitarist Jimi Hendrix’s version of the Bob Dylan song “All along the Watchtower.”

In his teens and early twenties Robinett played in a funk band and an R & B/Brazilian-jazz group. With each project he moved more toward jazz, inspired in part by the music of bassist and composer Charles Mingus, his father’s first cousin. After Robinett met Mingus in 1978, he wrote the jazz composer, saying that he dreamed of coming to live with him in New York City. Mingus called him and said, “Well, come on.” At the time Mingus was writing music for an album by singer-songwriter Joni Mitchell, and Robinett met her and many legendary jazz musicians during his three-month stay.

Robinett played briefly with the rock band Bourgeois Tagg in the 1980s before forming the Henry Robinett Group, which has released five albums, most recently I Have Known Mountains. (For more about his music career, visit henryrobinett.com.) In addition to his work in prisons, which is funded through the William James Association, he has taught at American River College, Cosumnes River College, and the University of the Pacific.

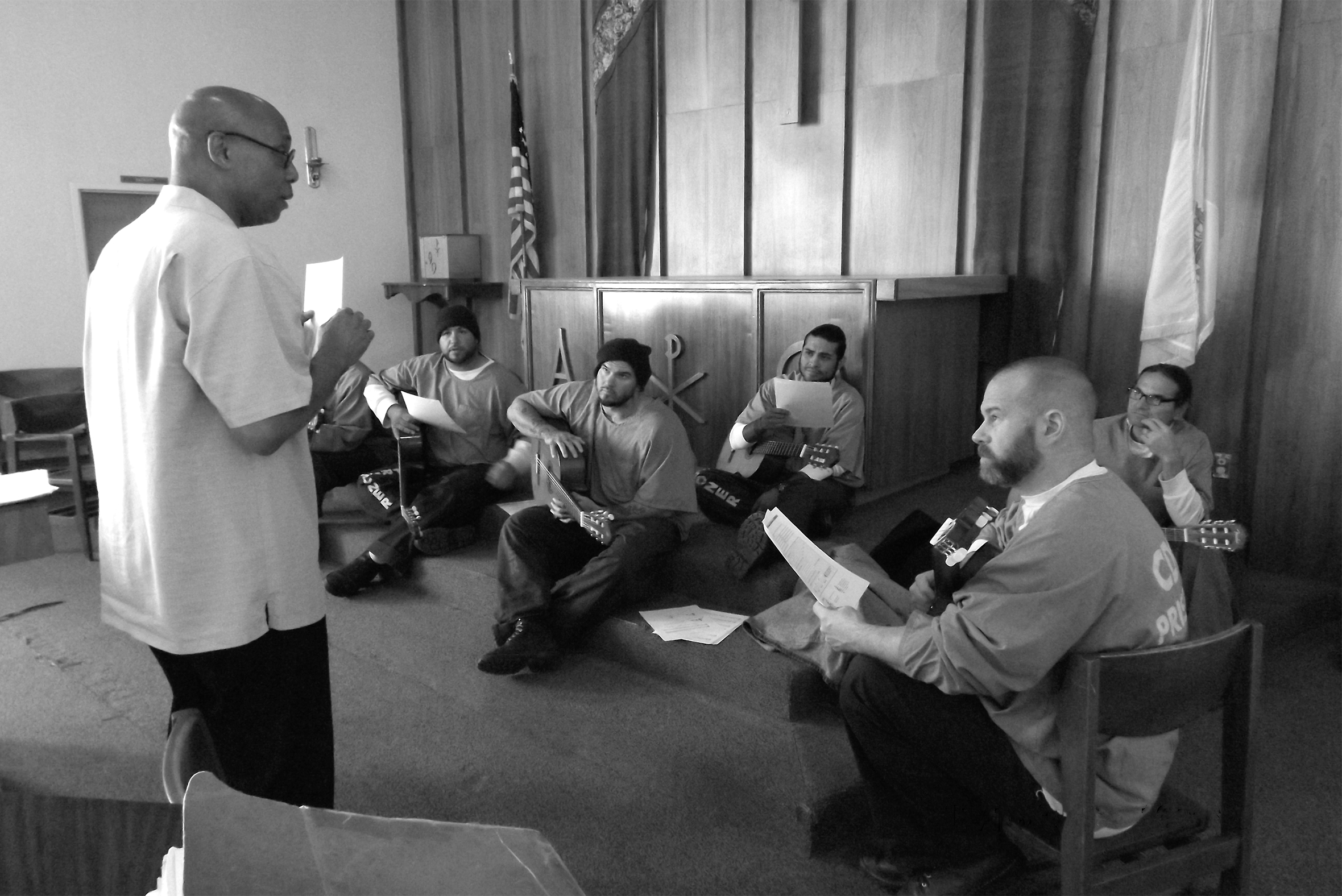

When we met for this interview, Robinett let me sit in on three of his classes at a state prison called the Sierra Conservation Center. He had a friendly rapport with his students, joking and nagging them about their homework. At one point he said that he’d never planned for teaching inmates to become his life’s work, but it turns out it is. He laughed, and his students did, too. Afterward one man told me the hour he spent in Robinett’s class every week was the only time he felt like a human being.

Carnes: Before you began teaching guitar at California’s Folsom State Prison in 1993, did you have any experience with prisons?

Robinett: No, this was a completely new world to me. I’d never even thought about it. I was hesitant at first. I’d taught guitar at a high school, and I’d had private students, so I wasn’t nervous about teaching. No, it was the environment. I didn’t know what to expect. I didn’t know who these guys were. I guess I thought they were bad people, and I think the media had a lot to do with that expectation.

My first class at Folsom Prison was in the hanging room. This was where they would hang people a hundred years ago. Being in that room filled me with an eerie sense of history, as if there were ghosts in the granite. The inmates were aware of it, too.

Carnes: What happened to change your perspective on the inmates?

Robinett: Most of them seemed just like you and me. There were a couple of scary incidents, but I didn’t have the feeling I would be harmed. I quickly overcame my fear, and I think that served me well as a teacher, because people can sense if you’re intimidated by them, or if you think they’re scum. It isn’t my job to judge these men. I treat the prisoners the same way I treat any other student — except I can’t give them a ride home after class. [Laughs.]

Carnes: How has this experience changed your view of prison?

Robinett: I think our system of incarceration is inhumane. These guys are allowed almost no dignity. As far as I’m concerned, their sentence is their punishment. They aren’t supposed to be treated cruelly on top of that. They have rights. Sure, they gave up some rights when they committed a crime, but not all.

Carnes: Do you know what your students’ crimes were?

Robinett: Not usually, no, and I don’t care. There’s one guy, William. I’ve known him longer than I’ve known anybody else in prison. He was in my first class in 1993. I don’t know what he did, but it must have been bad. He’s never getting out. Sure, I have a mild curiosity about his crime, but at this point there’s nothing he can tell me that would change my opinion of him. He is the person I know, not the person who murdered or molested someone or whatever. If we were all still held accountable for every bad thing we’ve done, we’d be in terrible shape. And, yes, most of us have never done anything that bad, but I think almost all of us have done something at some point in our lives that could have gotten us arrested.

Carnes: So teaching prisoners has helped you to stop judging people?

Robinett: Well, my wife will tell you that she and I still sit and talk about people on the street: “My God, can you believe what she’s wearing?” [Laughs.] But, yes, I think I can better suspend my reflex to sit in judgment.

One thing I’ve learned about myself is that I can talk to people who are apparently avid racists, and I can still see the humanity in them. When they talk to me, I don’t see a Nazi. I see a knucklehead.

Carnes: Have you ever found it difficult to suspend judgment with inmates?

Robinett: There’s one guy: He was always friendly with me, but I think he was a white supremacist. Once, we had to play a concert on the yard. Now, in class he played with black guys, Koreans, Mexicans — it didn’t matter. But when we had a public performance, he said, “Henry, I promised my mom I wouldn’t do anything to get myself hurt.” He had joined a gang that was keeping him safe, and he said if they saw him playing with a bunch of black guys, he could be seriously hurt. At least he was honest with me about that.

Carnes: What have you learned about yourself working with the inmates?

Robinett: I’ve realized that their rock bottom is way lower than mine. Almost all of these guys have done things that I can’t get my head around. There are some who have tried to make amends to society, even though they are never getting out. This one student of mine was about to be transferred. He and I were almost in tears, because I was going to miss him. I told him I was really proud of him. People on the outside, I said, most of us, our rock bottom only goes so low — maybe divorce or something. He said, “Oh, yeah, our rock bottom goes really low.” When I think of how far he climbed to get back up that ladder from the bottom, I just have to admire him. It sounds terrible, to admire a murderer. But I’m not talking about the person who did that crime thirty years ago, who went through ten to fifteen years filled with suicidal thoughts or rage. I’m talking about the person who climbed out. I look at people as they are now, whether they are behind bars or behind the counter at Starbucks.

In my first year of college I was fortunate enough to have poet Maya Angelou as one of my professors. She loved to quote some Greek playwright who said — I have to paraphrase here — “I am human, therefore nothing human can be foreign to me.” She made us think about that.

There was one student I had. I think he had caught his girlfriend screwing around and killed her and the person she was with, and then tried to kill himself. He felt terrible about it. I can understand the rage he had, if I’m honest with myself. Nothing human can be foreign to me.

Carnes: The prison system has been under scrutiny in recent years. Have you seen any positive changes?

Robinett: [California governor Arnold] Schwarzenegger changed the name of the California Department of Prisons to the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, but I haven’t seen a lot of rehabilitation. Inmates can go to school. They can try to get an education. But the overall environment is still oppressive. The prisons need to hire COs [correctional officers] who can be empathetic and aren’t on the job just to inflict pain or lord it over people. Most of the COs are good guys. Many are my friends. We joke. We laugh. The problem is, for every twenty guards who are good, there are three who are complete assholes. I have one inmate who wants to come to my class, but a correctional officer won’t let him. The CO just doesn’t like this inmate. I can’t do anything about it.

Arts programs — creative writing, drawing, music — enhance these guys’ lives. The arts give them a sense of the future. I give them something to practice and tell them, “If you keep working, you’re going to get better.”

Carnes: It’s good to have something to focus your energy on.

Robinett: Music kept me out of trouble. A couple of my friends got arrested for smoking pot, but that never happened to me. I was the ultimate nerd, always playing guitar. I was the kind of guy who would rather stay home and practice than go to a party. Plus I had a gig all through high school. Every Friday, Saturday, and sometimes Thursday night I was playing in a dance band. These inmates didn’t have that. What occupied their time was hanging out, stealing cars, selling drugs.

It’s an unusual marriage between the inmates and me. I’m as straight-arrow as they come. I don’t do anything illegal. I don’t do drugs. I don’t drive much over the speed limit. I don’t even download music I didn’t buy. Yet I don’t feel emotionally removed from these guys. Obviously I’m horrified by their stories. And of course I have sympathy for their victims. But I’m not here to punish. I’m here to try to enlighten.

Carnes: You may not know specifically what crimes your students have committed, but some of them must have been heinous. How do you feel about that?

Robinett: I assume they’ve all done the worst: murdered somebody, for example. But I also assume that most of these guys wouldn’t have done what they did if they’d really been cared for when they were younger. Regardless of what they’ve done, I can treat them with the respect that they don’t get from other inmates. And they certainly don’t get it from most of the correctional officers.

But I hate being at the prison. I think the conditions there are — no irony intended — just criminal. Arts programs can help, but they have their limitations. Anyone who’s been employed in an educational bureaucracy knows that the people who write the policy never see the actual students. The higher-ups really want arts programs to work, but they’re the arms. The correctional officers are the fingers and the hands. Time and time again I’ve seen the COs say, “Fuck this.”

Carnes: They aren’t wild about these programs?

Robinett: Not generally. The COs are being trained correctly and told all the right things, but it’s not getting through, from what I can see. There’s a lot of resentment. We have a band room with electric guitars and basses. The equipment is pretty torn up, nothing to envy. But I’ve heard COs say, “Man, I didn’t have that when I was growing up. And they get it for free?”

Carnes: You think that a lot of the problem rests on the shoulders of the correctional officers?

Robinett: Yeah, and I don’t know how to fix it. They get paid well. Maybe some of them just need to retire. These correctional officers tend to have an us-versus-them mentality. It’s a tribalism that gets magnified in prison.

Carnes: The inmates have their own tribes, don’t they?

Robinett: Sure, there are many gangs. I know a lot of Nazis and white supremacists and skinheads in prison. One thing I’ve learned about myself is that I can talk to people who are apparently avid racists, and I can still see the humanity in them. When they talk to me, I don’t see a Nazi. I see a knucklehead. [Laughs.] Or I see a person who wants to learn how to play the guitar.

Carnes: Did any of these white supremacists’ attitudes change as they got to know you?

Robinett: One of my first classes in Folsom was a jazz and R & B band — all black guys. I didn’t have any control over who was in it. On the first day of class I saw a bunch of white guys with swastika tattoos standing in the corner. It turned out these guys got together and played music one day a week. They had a blues band, which was kind of ironic. [Laughs.] Now we had taken their spot; they didn’t have a place to practice. So I walked over, introduced myself, and apologized. “I didn’t know this was your spot,” I said. I sensed a lot of resentment, but I just kept talking. Finally the leader said to me, “I heard you the other day. You’re a pretty good guitar player.” We shook hands.

I’d see their leader every once in a while after that, and he was always full of compliments. When I taught at the new Folsom, he took my guitar class and told everyone I was just great. I told him how I’d bought a Robert Johnson guitar book, thinking I could quickly learn some of Johnson’s blues to show him, but I couldn’t, and he laughed. He finally got paroled. I know that if my car broke down and a bunch of white supremacists came to beat the crap out of me, if he was there, he’d protect me.

Carnes: Is it common for arts teachers to have the kind of relationship you do with these inmates?

Robinett: I don’t know. One teacher told me she couldn’t work in prison anymore, because she loves these guys so much. She was in tears. She couldn’t take how they were being treated. Of course, there’s a real concern about overfamiliarity with the inmates.

Carnes: Why is that?

Robinett: You can easily be manipulated. I had one guy who wanted me to bring him pornography. He offered me money. I said, “I’m sorry, I’m not doing that.” When students want me to bring them music CDs, I don’t have a problem with it; it’s a guitar class. But I have to make sure I bring it for the class only and never leave it with them. That would be considered contraband. Once you do a few things like that, the requests escalate. If you get to the point where you’re bringing in a cellphone, then it’s serious trouble. Many inmates are classic manipulators. That’s how a lot of them got where they are. The institution wants us to fear these guys.

Carnes: But you don’t fear them?

Robinett: They’re human. Just imagine if you were in their situation. The only thing that’s going to turn them around is if people start treating them with humanity. I hate to say it, but love is what makes the world go round. These guys are starved for attention. I’m careful, but I tend to err on the side of giving them attention.

Carnes: Your philosophy seems to be “cautious compassion.”

Robinett: Yeah, if I could just teach the inmates who want to learn and not have the oppressive environment — the correctional officers, the bad inmates, the walls that are practically weeping — I’d love it. But no one’s going to let me control things. Nobody’s going to say, “Let’s try it Henry’s way.” [Laughs.]

Carnes: You definitely have a knack for teaching inmates. What do you think it takes?

Robinett: The same methods that work with my private students work in prison. I believe anyone can do anything; they’re just blocked from doing it. My job is to figure out how to unblock them.

Carnes: Is there anything unique about teaching inmates, or is the key not to view them as inmates?

Robinett: Yeah, that’s the key. They either learn or don’t learn for the same reasons as everyone else. Some of these guys have a guitar in their cell and never touch it. I get them to touch it, make some progress, experience small successes. If you think you’re going to have a huge success right away, you’re going to fail. But if you suspend the expectation that “I’m going to be the next Jimi Hendrix,” you will do well. I try to make them see that.

The first step is to establish a relationship. I’ll talk about my life, but I don’t get too personal. I’m not going to tell them where I live. I try not to say anything that might upset them too much. Like once I mentioned my dogs, and one of the men said, “Oh, man, I miss dogs.” I realized that he might never pet a dog again.

Some guys live vicariously through me. After Thanksgiving an inmate might ask, “What did you have? You had turkey, right?”

“Yeah, and I had sweet-potato pie.”

“Sweet-potato pie! Oh, my God!”

I’ve heard guys say that if a riot breaks out, I’m the safest person in prison, because they don’t trust the other inmates; they don’t trust the correctional officers; they don’t trust the administration. But they trust me.

Carnes: Do you have any success stories among your students?

Robinett: I had a student who hadn’t played in a long time. He took to it again and practiced nine to ten hours a day. After he got out, he joined a band that was very successful. But not every student wants to be in a band. Some guys just want to play a song for their wife or kids when they visit. Other guys want to write songs. I’ve worked with William on his writing. I give him feedback. He doesn’t want to be a jazz player like me, but he respects my opinion as a musician.

Carnes: When you first met William, what was he like?

Robinett: He was withdrawn, shy. I would not have thought he was particularly talented. He wasn’t one of my top students. But he took my classes on songwriting and theory, and I taught him how a song is put together. And he started to change. He’s also an artist and writes poetry, but I think music in particular saved him. He was able to put his heart and soul into it. Whatever dark place he came from, I think he has mostly left it behind. He can look back at it, though. He hasn’t forgotten. He will talk about it in bits and pieces. When I met him, he was probably suicidal. But he seems to have made peace with the fact that he’s never getting out. Now the other guys go to him for advice.

Henry Robinett instructs students at the Sierra Conservation Center.

Carnes: And you think the arts programs helped him with this?

Robinett: I don’t know what brought him out of his depths, but I think music played a large part. If it weren’t for guitar, he might not be around any longer.

Art defines our culture. It defines our humanity. Arts programs, creative writing, music classes — they expose these men to ways of thinking that they’ve probably never been exposed to before, because a lot of them have been dealt a horrible hand. I say, If you can’t look at that person in prison and love him, at least respect him and expose him to the world. My mom exposed me to the world. When I was nine, we lived in Europe. She took me to art museums. I heard jazz, musicals, symphonies, and operas. I saw a lot of the world that most people my age didn’t.

We are creative beings. Most of us just haven’t realized it. Maybe we are shunted away from the arts as children by parents, or school, or whatever. Maybe some boy’s father tells him he’s never going to amount to anything as a musician. I’m trying to reopen those channels for these guys. Only a few of us are lucky enough to find our passion.

Carnes: When your students get released, do these programs help them on the outside?

Robinett: I’m not supposed to be in contact with any of my students once they get out, but I can’t keep guys away from my gigs. I’ve had them come up to me and say that I will never know what I gave them. I don’t think it’s teaching them a scale or a different way of fingering a G7 chord. I think it’s treating them like human beings.

Carnes: You have a unique role in their lives: You’re not family. You’re not a correctional officer. You’re not another inmate.

Robinett: I’ve heard guys say that if a riot breaks out, I’m the safest person in the prison, because they don’t trust the other inmates; they don’t trust the correctional officers; they don’t trust the administration. But they trust me. I am in this rarefied category. They get something from me. I treat them with a respect that in some cases they don’t believe they deserve.

A college student of mine once referred to my prison job as my “life’s work.” That wasn’t what I wanted to hear. I consider the music I write to be my life’s work. But I have to say, if my major contribution is helping rehabilitate human beings through the arts, I am fine with that.

Carnes: If you could make changes in the prison system, what would they be?

Robinett: I’d drain the swamps. [Laughs.] I’d get rid of all the jaded, bitter correctional officers and start over with a new staff trained in methods that don’t come from the police culture — and not from the psychiatric culture either, because their solution is keeping guys zonked out on medication.

Caring is nonexistent in prison. I hate to sound like a Pollyanna, but it really comes down to human interaction. Things aren’t going to improve unless somebody cares about them. I saw this report on 60 Minutes about prisons in Germany. The Germans don’t see inmates as necessarily criminals for life. They see them as people who made a bad decision, and now they have to pay for it.

We’re all responsible for our actions. I don’t want to minimize what these men have done. I had this one guy in my music program, a real tough white guy: bald head, tattoos. He was part of a motorcycle gang. We’d banter back and forth. One day I said in passing, “Too bad I didn’t know you on the outside.” He said, “Whoa, dude, you did not want to know me out there.” I tried to brush it off, but he wouldn’t let it go. “I was not the kind of person you ever wanted to know,” he said.

Last Tuesday I was talking to a man who’s doing life. I said, “Most guys in here are guilty.” And he said, “Yeah, most of us. We did it.” So I wouldn’t let everyone out. But if they do well and can be trusted, I’d let some prisoners get jobs on the outside. And I’d let them see their wives and kids on the weekends. I would make sure they have access to an education. This is where a lot of people say, “Yeah, right, these guys murder someone, and then you’re going to reward them?” I don’t think of it as rewarding. I think of it as realizing that this is a damaged individual. Maybe I can’t fix everything that’s wrong with him, but I don’t need to add to it.

Probably one of the largest failures of the prison system is a lack of educational programs. I don’t mean all inmates need to get a degree in something, but each one should be exposed to the world. Knowing how to play a musical instrument is healing and educational in ways that are ineffable.

Carnes: So a proper education and some training in the arts are necessary components to rehabilitation?

Robinett: Yes. Keep in mind that a very small percentage of these men are sociopathic. Nothing is going to change them. And another 20 percent or so don’t want to change. But most of them are just people who messed up. They hung out with the wrong crowd. They made the wrong decisions. One guy had a really tough life. His dad was a homeless alcoholic. His mother was a prostitute. He wanted me to teach him a song called “Drink a Beer” — a country tune. I can’t remember who wrote it. I asked him, “What’s so special about this song?” And he said, “It’s my dad. I would sing this song for my dad if he was alive.”

Carnes: Do you have hope for most of the inmates you’ve met?

Robinett: I do. One guy e-mailed me yesterday. He had taken my class at the old Folsom and just wanted to see how I was doing. This guy said I’d changed his life. He wasn’t a particularly talented musician, but he had continued playing music in some capacity. I think there’s definitely hope.

Carnes: What do you think is the main reason these men take your class? What do they want to get out of it?

Robinett: A lot of them are just bored out of their minds. Or they always wanted to play guitar but never could. Or they used to play guitar and want to get back into it. I try to accommodate them all. I always say there’s a make-or-break point for learning an instrument. It’s when you start thinking, “This sucks. I suck. My hand hurts. Why do I have to play this D chord? I hate my teacher.” But if you push past that and just learn to play “The House of the Rising Sun,” you begin to think, “I’ve got this.” Then you’re self-motivated and will continue.

It’s getting students beyond that point that’s the hard part. The reason they originally wanted to play evaporates relatively quickly. I think teachers in all fields understand that the student has no real idea what he or she can get from the subject. The teacher has the long view. The student can only see so far ahead.

Carnes: You said learning the guitar is a healing experience for these men. Do you present it that way to students?

Robinett: No. There’s a teacher at Sierra Conservation Center who has his own program called Arts and Healing. He and I have some arguments because I’m not an “arts and healing” guy. I’m not a musical therapist. I think musical therapy is interesting. It has its success rate. I have no doubt about the healing power of music in general. But I’m not trying to heal people. My job is to teach this guy a D chord, and a G chord, and a C chord, and then get him playing some tunes. If I focused on the larger purpose as opposed to the nuts and bolts, then I’d lose everything. I have to form a relationship with the student that allows him to trust that I care about him and that playing this chord over and over again is worthwhile. With time, I hope, he’ll be able to express himself through art, because I think that’s the greatest thing a human being can aspire to.

But learning an instrument takes discipline. Last week I taught my students the introduction to Chuck Berry’s “Johnny B. Goode.” We just played this one solo again and again. We were next door to an art class. A couple of guys from the art class came over and said, “This is driving me crazy.” [Laughs.] I tell people all the time that if everyone knew what it really takes to be a musician, how many times you have to play something to get it right, either there would be a lot fewer musicians, or there would be more accomplished musicians. Most people think some just have talent and others don’t. Maybe there’s a little bit of truth to that, but you would be surprised how little. What it comes down to is hard work. I have had students who I swear had no talent at all but ended up with a career in music because they worked at it.

I’m not trying to heal people. My job is to teach this guy a D chord, and a G chord, and a C chord, and then get him playing some tunes. If I focused on the larger purpose as opposed to the nuts and bolts, then I’d lose everything.

Carnes: Are your classes spaces where yard politics can be set aside?

Robinett: Yes, guitar class is a safe haven. I don’t know why. I think art touches something sacred, something protected.

There was one time, though: We had a band program, and two inmates had to share a trumpet. One man was black, and the other was white. They were both good musicians. Neither of them had a problem using the same trumpet. But the Aryan Brotherhood found out about it and sent someone to tell me, “This will not stand. We can’t have a white trumpet player putting his lips on an instrument that a black guy was playing.” The black gangs — the Crips or the Bloods or the Black Mafia — had no problem with it. I told the Aryan Brotherhood this was racist bullshit, and I would have nothing to do with it. But if the trumpet players continued sharing, one of them could have gotten stabbed. So the black guy dropped out of the program. Other than that one time, the band program has been neutral territory where yard politics don’t apply.

Carnes: You work in an environment where race is a life-or-death issue. How does that make you feel?

Robinett: Like all white people are assholes. [Laughs.] No. First off, it makes me wary of the correctional officers, because that culture seems particularly white. One time I asked a CO for the keys to the gym where we were having class, and he said, “Oh, yeah, sure, be right there.” And he kept talking to his buddies. I said, “Hey, I need the keys.” “OK, cool. I’ll be right over.” Nothing. The inmates saw me being disrespected, but they were powerless to do anything about it. Maybe it was racism; maybe it was resentment: The CO might have been thinking, “How come these guys are having a guitar class? What the hell. These guys are scum. I’m not going to lift a finger to help them.” I had to deal with it every time I went to teach that class, until I could finally pull the keys myself. There was one Hispanic CO; he was always nice. He would let me in.

Carnes: I’m still thinking about that trumpet story. Do you think the white gangs are more racist than the others?

Robinett: They are offended by interactions with minority groups. Minorities aren’t offended by interactions with white people. Here’s a story a student told me about his friend, who was a middle-aged white guy, and was best friends with a black guy: They used to play basketball together. One day it was really hot, and the black guy took a sip out of the white guy’s water cup. The white guy said to his friend, “You can’t do that. You’re going to get me killed. I love you like a brother — you know I do — but you can’t drink from my cup.” Black guys don’t care if a white guy sips from a cup. Black guys don’t care if someone shakes a white guy’s hand. The black guys fight over turf or selling some product. If someone is getting into their territory, it’s over.

Carnes: What do you think the ultimate purpose of prison should be?

Robinett: Protect society, number one. We should take you off the streets if you can’t interact safely with others. Number two should be to make sure that you are fit to reenter society after you’ve done your time. If we just throw you in prison and call you an animal and a scumbag, you’re never going to come out ready to be a responsible citizen. You’ll have no respect for society because, in your mind, society has done you wrong. It comes down to treating people with the respect that we would want to be treated with.

Society, too, needs to be reeducated. Instead of thinking prisoners are scum, we should realize that, but for the grace of God, we could be in that situation. Instead of making it difficult for guys who do get parole, we should try to provide work for them. Once they’ve done their time, their punishment should be over, unless they offend again. We need to start caring about these people, because we all have the uncle who screwed up, or someone in our family who’s done something wrong, and most of us still care about those people. We might not want to see them at Christmas, but we care. Society isn’t going to heal people by kicking them and incarcerating them and forgetting about them.

I keep going back to that phrase that Maya Angelou taught me: “I am human, therefore nothing human can be foreign to me.” Most people don’t think like that. They think inmates are different in some way. The big lesson is that they’re not.