We rent a condominium together, my eighty-six-year-old widowed mother and I. Sometimes she summons me from her bedroom at the end of the hall. I have learned to guess from her tone what it is she wants. If she cries my name with a note of dismay, it means something has been misplaced — the silk scarf she wears to Mass; a library book; her yellow wig pick, which reminds me of a harp. I always find the lost item under a pillow or beneath the white-and-blue quilt that warms her feet. If she sounds upbeat, I know she is calling to remind me it is time for one of our regular outings: We go to Mass on Saturday evenings. We spend Sundays in our beloved library. And twice a day we go for a walk — well, I walk, and Mom lets me push her in her wheelchair. We chat and point out birds and bright flowers to each other as I roll her along the smoothly paved streets of our San Diego neighborhood: Lomica, Palomar, Pastoral, Santiago. On Meandro we pass a wooden stairway, the weathered ash-gray boards leading up a steep hillside dotted with bougainvillea. Mom always looks up those steps and says that tomorrow she’ll climb them.

Today, when she calls my name, it has a quizzical ring to it, as if she has an idea for an unusual outing — the movies, perhaps, or a picnic in the park — and wants to find out whether I approve.

Her summons has broken my concentration at the dining-room table, where I’m studying for a master of fine arts degree. I look toward the narrow hall. It’s a wonder Mom can get her wheelchair down it each morning for breakfast. The scarred doorjambs bear witness to the difficulty.

Here is a typical morning for us: She wakes about 3 AM, and I stumble from my room as she rolls past wearing an auburn wig that looks like a shrubbery. She says it gives her “bounce,” and it does. Her real hair, which I see as I tuck her into bed each night, is an aged blond, pulled back tight and held in place with a rubber band — a hairdo that makes her look severe and worried, like a retired nun.

“Mom, it’s three in the morning,” I say. “Let’s have breakfast later.”

She says I can go back to bed; she’ll make breakfast herself.

“I’m up, Mom,” I say. “You rest.”

And I push the bread down in the toaster and heat the water for her tea. My mother’s gratitude for the smallest kindnesses always makes me chide myself for grumbling.

I leave her to her meal and lie down till I hear the telltale clink of her empty cup on a saucer; then I get up to help her back down the narrow hall and tuck her into bed. “Go to sleep, Mom,” I say. “Not even the birds are up yet.”

Sometimes she rolls down the hall for a second breakfast at five, as if she has forgotten the first.

“Philip!” she calls now.

“Coming,” I say, pushing aside the textbooks. A house painter by trade — “Twenty-Eight Years Painting Houses by the Sea,” my business card reads — I’m taking a sabbatical to finish my education. Two nights a week I sit in class and take notes and worry about leaving Mom home alone.

Everything I read for my courses feels startlingly important, and I share much of it with my mother. I might tell her how, in his old age, Titian painted mostly with his fingers, or how Tiepolo’s wife gambled away his Venetian paintings: “Imagine, Mom: all that beautiful work lost on the toss of a die.”

She loves learning as much as I do and always has a book in her lap. Twice now, on our weekly trips to the library, she has slipped books under her wheelchair seat and, when the alarm went off at the exit, given me a “Now, who put those there?” look.

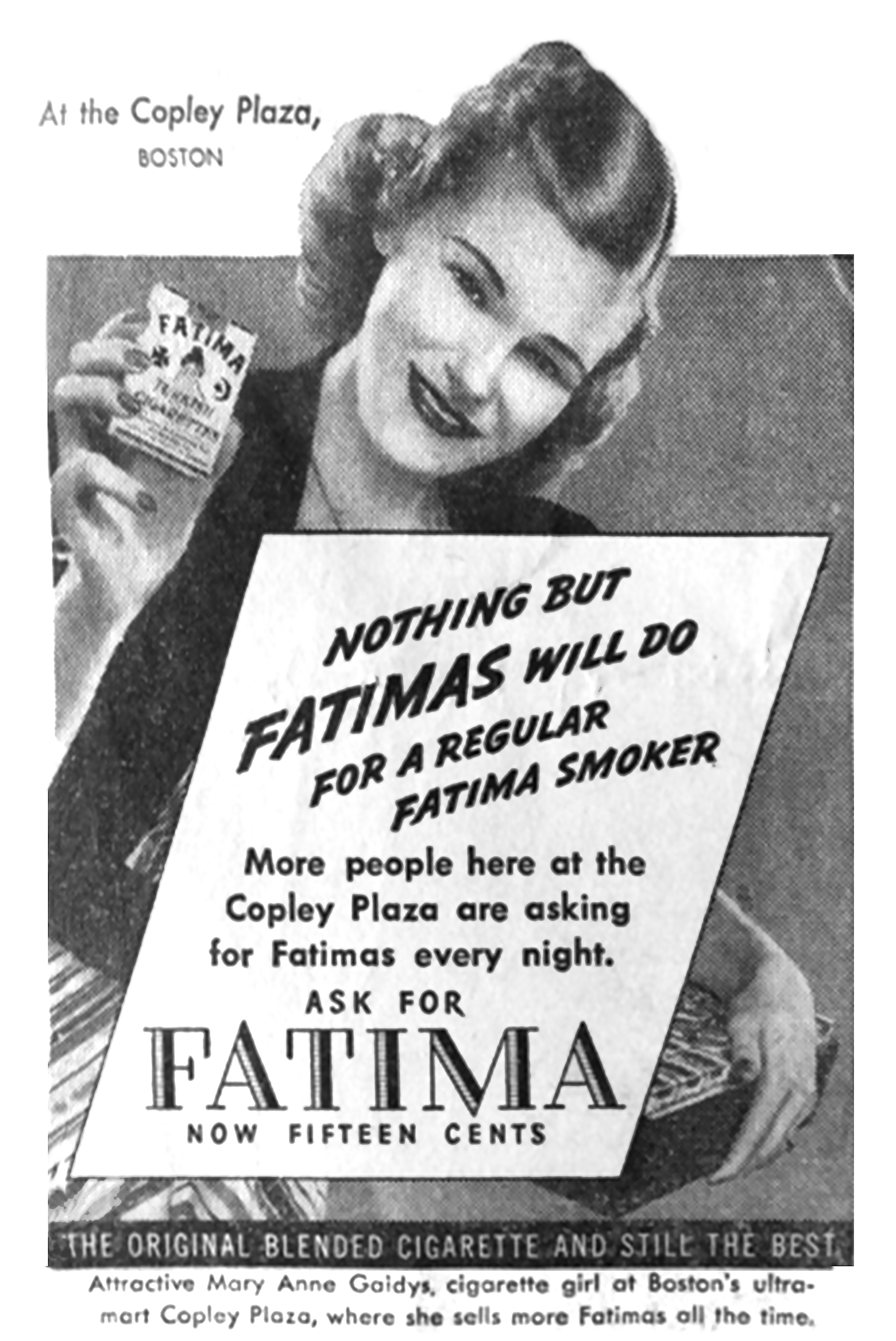

In the 1940s she frequented the public library in Copley Square, Boston. She’d go there each day on her break from her job as a cigarette girl at the Copley Plaza Hotel and read, read, read — mostly travel books. She never finished high school. All they taught girls back then was how to cook and sew anyway, and she was interested in neither. She wanted to see the world. In a picture from 1941 she is gorgeous: platinum-blond hair, high cheekbones, and a wide smile. Fatima cigarettes used her as a model to sell their product, and the Toronto Maple Leafs hockey team wanted her to be their mascot. She declined and married my wealthy father instead. They moved to Del Mar, California, and later Hawaii. I think she was happy there, but her shyness kept her from making friends. She was polite, but her door was never wide open to others. Her family was quite enough for her. She cautioned my siblings and me not to trust everyone we met.

My brother and sister rejected this view and weren’t close to Mom growing up. I was the middle child, her favorite. Like her, I was shy and loved books and traveling. After she became a widow three years ago, it was clear I should be the one to watch over her. She was in a senior-living apartment at the time — still no friends, just polite nods to the other women who lived there. I’d come down to San Diego to spend weekends with her. We’d watch Washington Week on Friday nights, and on Saturday and Sunday I’d take her to the movies and to the library and to Mass.

On one visit I found her much too thin. She’d been missing meals, the attendants told me. Since my dad had died, she’d had a table in the dining room to herself, which had been fine with her. But recently the administrators had assigned her a new dining partner. I’d met her tablemate — the nicest woman you could imagine — but Mom couldn’t be social three times a day, so she’d simply stopped going to meals. I had to bribe the cook with Chargers tickets to let her return to eating alone.

A few months later I told Mom I wanted to go back to school and get my master’s. She and I were holding hands at a picnic table surrounded by yellow-green grass. It was spring. The sound of bird song was in the air — cactus wrens and yellowthroats. Our backs were against the table, and Mom was swinging her legs like a child.

I presented my plan: Perhaps, with an advanced degree, I could finally put down my paintbrush and become a teacher. Up in the hills outside San Diego, I explained, among the brown chaparral and live oaks, there was a campsite where I’d pitch my tent to save on rent. I’d take classes during the day and sleep under stars at night. We’d still have our weekends together. And I’d call her every night on my cellphone.

I waited for her response.

“It will be hard,” she said, “but you can do it. Nothing is more important than your education.” She tapped the redwood table with her fingertips, as if nailing the plan in place. “I’ll say the rosary for you each night after you call!”

We shook hands with great solemnity.

The author’s mother, pictured in a 1939 cigarette ad.

Buoyed by her encouragement and rosaries, I got into grad school. Instead of a tent I bought a used twenty-four-foot travel trailer, which I set up in a state park close to both the university and Mom. I filled my head with knowledge each day and fell asleep to the sound of hooting owls at night.

Things were going well until, on two successive New Year’s Eves, Mom fell and broke her hip: first one, then the other. I was home with her each time, lying on the couch, watching the live broadcast from Times Square on TV, and then frantically calling the ambulances.

After the second fall the doctors and hospital officials wrote off Mom’s chance of recovery and placed her in a convalescent home. In my dark trailer at night I dreamed I was reaching out to her and finding only thin air.

Finally I decided that this was our life, and I wouldn’t let any experts tell us how to live it. Once again I went to my mother with a plan.

I found her on the sad patio of her convalescent apartment, sitting in her wheelchair in the shade of a towering jacaranda and vacantly watching men sip from brown bags outside the liquor store across the street. Occasionally a blossom from the jacaranda would parachute down and land on her shoulder. There was no book in her lap — a bad sign.

“Mom?” I began.

She turned to me wearily.

“Do you want to be roommates?”

I told her I had already rented a condo near where she and Dad had lived, a pretty place on a hill. She could shop at the same stores, attend the same church. It had a screened porch that would be perfect for afternoon reading. “What do you think?”

Mom immediately laughed and rose — she rose! — to go.

We left that day. I transported her meager belongings to my car and settled her in the front seat with a book and a sandwich. Caretakers scurried. Papers were brought out for our signatures. We were breaking protocol, but they couldn’t stop us. We have lived together ever since.

“Philip!”

“I’m here.”

Mom still has the maple bedroom furniture she and my dad received as a wedding present all those years ago in Boston. On the nightstand between the twin beds are a prayer book, a box of tissues, a silver rosary with onyx beads, and a porcelain lamp decorated with the image of three laughing Chinese monks with fishing poles chasing one another. (This is the light I click off as I tuck her in each night.) A Mexican blanket is draped over a ladder-back chair with a woven straw seat. A cedar chest holds photo albums and boxes of letters. In an oil painting my great-grandmother on my father’s side sits serenely, clothed in black except for a white collar and a pearl pendant, one loose gray hair falling across her forehead.

My mother sits by the window, spring sunlight playing over her. She is wearing her favorite sweater, a robin’s-egg blue with gold thread at the wrists. The bouncy auburn wig covers her head, and a book rests on her lap; she is keeping her page with a finger. The skin of her hands is like parchment, the indigo veins like writing. Outside, the branch of a Russian olive tree brushes against the window screen.

“I can’t read the time,” my mother says.

On the wall is a clock I bought her because of her love for birds. In place of numbers, it has drawings of a cactus wren at 1, a mockingbird at 2, and so on. The hourly chimes are their songs.

I offer to move the clock to the other wall, closer to her.

“No,” Mom says. She taps the bed next to her for me to sit, and I do. She takes my hand. “I can see the clock,” she says. “I just can’t read the time.”

So this is it. I’ve been aware of the hints here and there: the books in her wheelchair at the library; the forgotten breakfasts — all the subtle signs of dementia. Once, on an outing, she cautioned me to drive slowly because my deceased father was napping in the back seat. Then she turned to me and winked.

I’ve tried to explain away these slips, putting them down to a poor night’s sleep, the heat, the realignment of the magnetic poles. But I know this is it: the moment that will divide my life with her into a before and an after. I sit for a minute with this knowledge before making one last attempt to pretend I can fix everything: I promise to get her a digital clock with large numbers — no more hour and minute hands, no more birds.

She pats my hand as if telling me to relax, and I stop talking. The Russian olive brushes the window screen again with its bright-green spring leaves. A cricket sings in the grass outside.