I was seven years old when the planes crashed into the World Trade Center. Seated in a church pew at the Catholic school my parents sent me to (even though we were Muslim), I didn’t really understand the news that Father Mike was delivering to us. As I sat there confused, a group of students next to me began whispering about the “Arab terrorists.”

Later I went home and wrote in my sequined pink journal: “I want to be white.”

That same day a group of boys tried to beat up my brother behind the church. When he fought back, he was taken to the principal’s office.

My older sister’s middle-school peers told her to “go back to Mexico.”

It was hard growing up half Palestinian and half white in Michigan City, Indiana. My sense of identity was as mixed-up as the food at our family barbecues, where hot dogs and tabouli salad shared the same plates. At school I learned about the saints and Scripture. At home I prayed on a prayer rug facing Mecca.

Years later, when my family moved to California, I naively thought I would finally belong. On my first day of high school a curious classmate asked the origin of my name.

“It’s Arabic,” I responded, almost proudly.

He laughed and asked, “Are you going to blow up the school?”

L.A.

Oakland, California

In my second year of college someone dares me to apply for a summer job as a firefighter with the California Division of Forestry. This is in 1976, and, as far as I know, only males are hired for this job. Though I am a female, I accept the dare. I send in my application, thinking it will be denied. To my surprise I receive a response with a date and time to take a physical test. If I can pass it, I will be given an interview.

On the day of the test, there are ten physical challenges I must complete. If I fail a single one, I don’t get an interview. Thinking I have no chance, I approach each challenge relaxed and, to my amazement, complete them all easily. Toward the end, the fire captains line up to cheer me on as I pull myself over a ten-foot wall.

Next I am escorted into a room, where I find out that the California Division of Forestry is running a pilot program for female firefighters. If I am hired, the position will pay more than I’ve ever made in my life. I will have to cut my long hair so it does not touch the collar of my uniform, but I don’t care.

That May I become one of the first female firefighters in Northern California. The region is having its worst drought in years, which means this will be a dangerous fire season. Nine young males and I are stationed at Glen Ellen in Sonoma County. I am determined to do my best and open the door wide for the women who will come after me. To my surprise my fellow firefighters are accepting of my presence. Of the two captains, one is supportive, and the other makes it clear that a woman has no business in a firehouse.

There is one Latino and one black guy on the crew. The three of us are assigned to the same fire truck, and we form a bond. They help me find ways to utilize my strengths. I am determined to pull my own weight and be the first one on the truck at the sound of the bell.

That summer we fight fire after fire, up and down hillsides, cutting trenches with hand tools and, when possible, spraying the flames with a hose from the truck. It is grueling, hot work. I do it well, shoulder to shoulder with the guys.

Sabrina Spear

Sebastopol, California

I am biracial. When my parents met, my white mother was living in Hawaii and working as a nurse. My Chinese father, who had lived in Honolulu his whole life, was working as a car salesman. He tried to sell my mother a car. She didn’t buy the car, but they did start dating. Eventually they got married. It was a second marriage for both of them.

When I was eight, we moved from Honolulu to a suburb of Seattle, where my mother had grown up. In Hawaii my sister and I had been hapa — half white, half “local.” For some reason this was (and still is) seen as the ideal there. In our mostly white mainland community, though, we were considered just white.

I first learned in fourth grade that half of me could be erased: I have a half-Japanese half sister from my father’s first marriage, and after a lesson about the Japanese internment during World War II, I asked my teacher what would have happened to a family like mine during that time. She assumed I was just worried about myself and assured me that I would have been fine; no one would even have known I was Asian. I suddenly realized that I was different from many members of the family I’d grown up with, and that those differences came with privileges. I was nine years old.

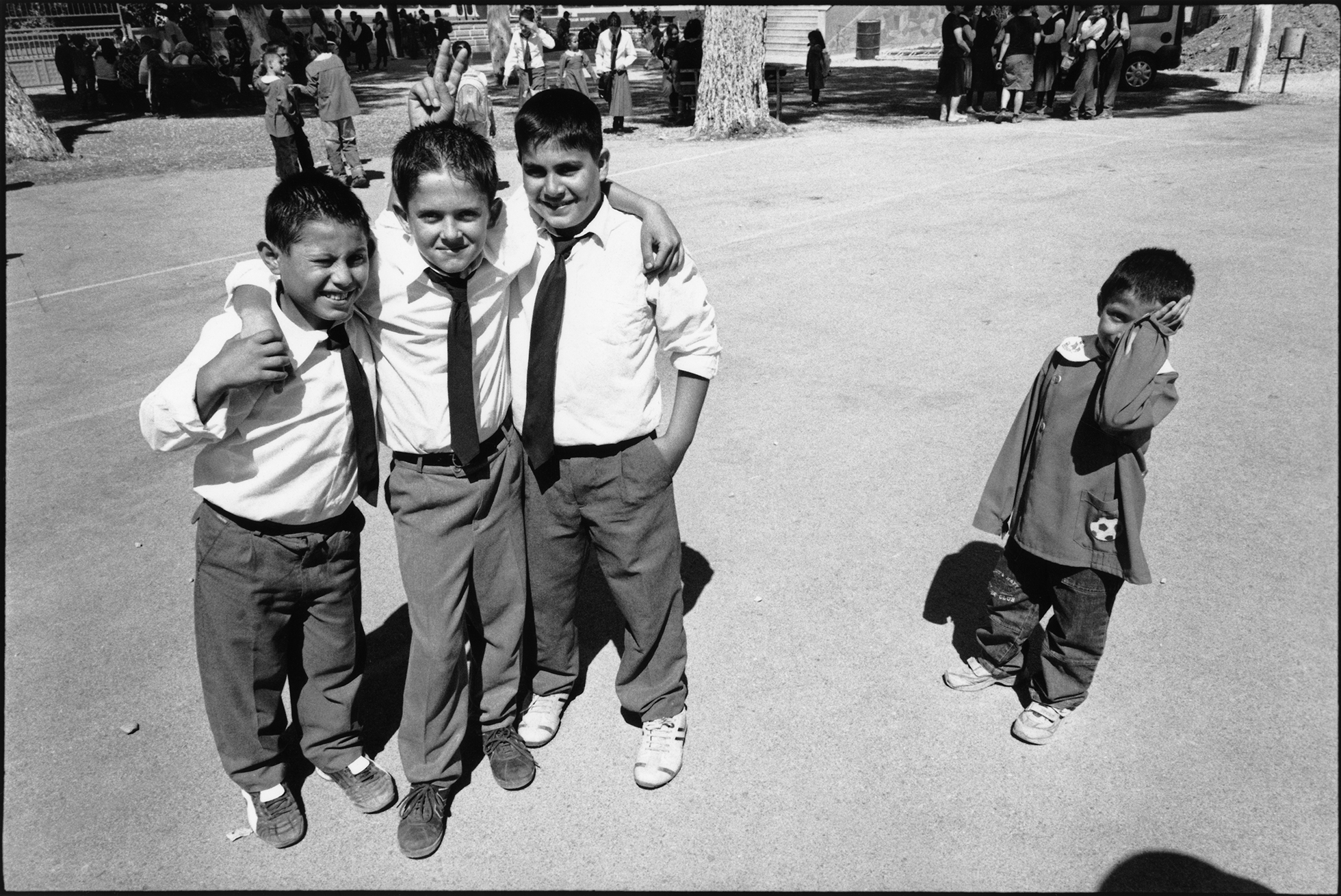

A decade later, for my undergrad senior project, I spent a year photographing and interviewing biracial Americans. Working on the project, I felt an urgency I hadn’t expected. I had never talked openly about growing up biracial, and I had met only a few other biracial people. As my subjects shared their sad, funny, relatable stories of ethnic ambiguity and mistaken assumptions, I became so engaged that I often forgot to take notes. I could only think, Yes, me too. Over and over, my subjects and I arrived at the same conclusion: that we fit in everywhere and nowhere all at once.

Kristin Leong

Seattle, Washington

Among my siblings and circle of friends, I’m the first to have become a widow.

A few months after my husband died, his sister called to see how I was doing. I was in the middle of sorting through his things, deciding what to keep, what to give away, and what to discard. I described the process to her.

“Are you still in mourning?” my sister-in-law cavalierly asked.

Stunned, I didn’t answer. A long moment of silence went by before she expressed regret for her poor choice of words and admitted she had no idea what I was going through. I told her it was OK — which wasn’t exactly true — and we moved on.

One of my oldest high-school friends stopped by. At the kitchen table over coffee, she said in a kind voice, “You really look great.”

“People say that to me all the time,” I replied, assuming I could be honest with her. “I never know how to respond. ‘Great’ as opposed to what? What does everyone expect me to look like?”

My friend stared at me for a little while, then said, “You could just say thank you.”

I dreaded attending my nephew’s wedding reception alone. At the same time, I didn’t want to miss it. I love weddings and my nephew. Besides, I had already declined two wedding invitations since my husband’s death. It was time.

The ballroom at the reception was packed. I found my table and enjoyed the company of people I’d known for more than forty years. It was a happy day, and I felt at ease among my husband’s family. Then the loud music started, and conversation became out of the question. I rose from my seat and stood at the edge of the dance floor to watch the couples shimmy and twirl. Recalling dance classes with my husband and dinner dances and wedding receptions like this, I yearned for the one person whose lead I could always follow. I was filled with sadness — until I saw my son-in-law crossing the room toward me.

God love him, he asked me to dance.

M.M.

Wanaque, New Jersey

In sixth grade I was shy and lacked confidence. During physical education a friend encouraged this tendency by teaching me how to avoid being at bat in softball: we slyly worked our way backward in line on the bench. Our teacher, Mr. Rodney, eventually caught on and made sure we took our turns at bat.

Then we had a unit on track, and I discovered I had a natural ability for sprinting, winning the twenty-five- and fifty-yard dashes. I also excelled in the long jump, broad jump, and high jump.

When an interschool track meet was organized, Mr. Rodney assembled his best athletes. I was the only girl on the team. On the day of the meet we piled into the bus and rode across town to the host school. I warmed up with my teammates, excited about the competition, not noticing that I was also the only girl at the meet.

The officials called Mr. Rodney over, and after they had spoken, he pulled me aside and relayed their message: I would not be allowed to compete. I don’t know if they were too dumbfounded by the concept of a girl athlete in 1959, or they were afraid I would outrun or outjump the boys. Track was not a contact sport, so they couldn’t hide behind that excuse. Whatever the reason, they had whisked away my chance for accomplishment and recognition because I was not a male.

Gwen Willadsen

Chico, California

Arriving to attend a birthday party at McDonald’s, I handed my friend’s mother a carefully folded note and looked away while she read it.

“Thank you,” she responded sympathetically. “You may go play.”

At the age of eight I was used to this reaction, but that didn’t make it any easier.

The note was from my mother, who believed that Happy Meals and Coca-Cola and birthday cake were like poison and not to be consumed, ever. I could have milk and a burger with no bun, cheese, ketchup, or relish. No fries, either, no soda, and no dessert. I was allowed to breathe, but that’s about it. While the rest of the kids ate treats, I sat in the corner and watched with a mixture of bewilderment and curiosity.

On Halloween other children ran from house to house, filling pillowcases with Tootsie Rolls and Skittles. Meanwhile my mother would drive my sister and me to her friends’ homes, where we received apples, walnuts, quarters, raisins, and pretzels from adults wearing apologetic expressions. At Easter we got stickers and bunnies made of carob, a disappointing chocolate substitute. In the school cafeteria I would carefully unwrap my 100 percent whole-wheat sandwich with natural peanut butter, banana slices, sunflower seeds, and alfalfa sprouts. My friends ate their Twinkies and Lunchables and made snide comments about how my peanut butter looked like poop.

On my own birthday I had a party and requested “jello cake” for dessert. In my house “jello” was pectin mixed with all-natural fruit juice. My favorite was apple-strawberry, which we bought by the case. It came in a glass jar and was the color of muddy water but tasted delicious.

My mother brought out the cake while my classmates sang “Happy Birthday.” My excitement dissipated when I saw the disgusted expression on everyone’s face. No one would even try the brown jello. They were accustomed to shades of fluorescent green, red, and orange. I held my head high and ate a large slice anyway. They didn’t know what they were missing.

I currently own a natural-foods store, cafe, deli, and catering business. I’m raising my son on an organic, whole-foods diet. But he’s allowed to eat cake and go trick-or-treating, and he has no idea what carob tastes like.

Wynde Reese

Keene Valley, New York

I taught English to high-school freshmen who were designated “at risk.” My co-teacher and I tried to teach our students not just about literature and writing but also how to get along better, how to drop their anger and think of others’ needs. The teens sometimes resisted these lessons.

One day, toward the end of the school year, a young man I’ll call Mike stood at the front of the classroom to deliver a book report. Mike had a large red birthmark that covered half his face. He kept to himself most of the time and rarely smiled. On this particular day he scowled at the class and delivered his talk with a snarl. As he plopped back down in his chair, a girl said sincerely, “Good job,” and he muttered something rude to her. Another girl, known for her temper, yelled at Mike, asking why he was so mean to people who were just trying to be nice to him.

Before my co-teacher could step in, another student said, “We need to do a circle to talk about this.”

Circle was a ritual we had created so our students could practice speaking and listening to each other. I wasn’t sure it was appropriate to hold a circle about one student; I worried Mike would be attacked by the group. My co-teacher asked Mike if he wanted to do it, and he snapped, “OK.”

The student who had called for the circle held the “talking stick” first. (The rule was that whoever had the stick had the floor, and everyone else had to listen without interrupting.) This student suggested that Mike kept people at a distance so they wouldn’t make fun of his birthmark. There was a pause. No one had ever mentioned Mike’s birthmark before.

As the stick went around the circle, several students seconded this observation. One pointed out that everyone there had probably been made fun of for something, “and we don’t go around treating everyone like crap.” Others began sharing how they had been made fun of in their lives. Pretty soon they were all laughing at themselves and their experiences — except for Mike, who sat in silence. Finally he took the stick to speak.

Mike told the other kids they were right. He was sorry. He would try to be nicer. They all cheered, the bell rang, and they left. It felt surreal. Things could easily have gone the other way, and Mike could have ended up hurt. But at least on that day, for those kids, talking about difficult feelings worked.

Name Withheld

When you have Parkinson’s disease and you live alone, you have to pay someone to clean for you, and sometimes you have to take taxis to doctor appointments. This isn’t cheap. You would like to get a roommate to share expenses, but you don’t want to advertise on Craigslist, because you don’t know what kind of person will respond. You find a website that matches women over fifty with roommates, but then you read the frequently asked questions, and it says they won’t accept anyone with disabilities. One of the aides who helps you in your home says she has a coworker who might be interested in being your roommate. Then the aide sees you on a day when your meds are not working so well, and you overhear her on the phone telling the coworker it would be too much trouble living with you.

When you have Parkinson’s disease and your friends are getting together for lunch or to go shopping, they sometimes don’t call you. It’s not that they don’t want to spend time with you; it’s just more difficult when you’re involved. You don’t drive, so someone has to pick you up, and they have to choose a place that’s easy for you to access. You don’t get invited on trips to the mountains or the lake or the beach either, even though you’d like to see those places, too. You try not to be needy, but you feel less like a friend than an obligation. Friends do help you with errands; they just don’t stay to spend time with you. They have other friends for that.

When you have Parkinson’s disease, you hope for a new treatment or a cure. You don’t want to be remembered this way, but you, too, are starting to forget the person you used to be. Even in your dreams you have trouble walking.

D.D.

Knoxville, Tennessee

I met Sara, the new girl in town, because our fathers worked together and my dad made me walk down the street and introduce myself. On her first day of middle school I was supposed to show her around, but I tried to avoid her instead. Sara just didn’t fit in, with her faded blue jeans and flannel shirts. The other girls and I all wore short skirts. Sara’s thick glasses and headband were out of fashion, too, and she rarely talked. When she did, her husky voice stood out.

At lunchtime my friends encouraged me to ditch Sara. As the year went on, they made up rumors that she stole people’s lunches out of lockers and smoked pot and was having sex with the losers who hung out by the creek after school. I didn’t believe them, but there was definitely something odd about Sara.

Because we were neighbors, Sara often sought me out after school to walk home together. On the way, we would talk about books and make jokes about our history teacher, whom Sara could imitate perfectly. She made me laugh, and I liked being with her, as long as no one else was around.

One weekend I planned a party at my house and had to decide whether to invite Sara. As a Christian, I knew I should have compassion for others, but I ended up not giving her an invitation. I felt ashamed.

On our walk home one day Sara was quiet. Worried she’d found out about the party, I asked what was wrong. She explained that she was in trouble at home, and her father was waiting to punish her. She would likely be locked in her room without books or food. Apparently it was typical for him to inflict harsh punishments for small offenses. One time, in a fit of rage, he’d hit her so hard that he’d broken her arm.

I was horrified but not surprised. After all, my father was an abusive alcoholic. I knew what it was like to live with uncertainty and fear, to want to be invisible. From that moment on I began to look at Sara differently.

This was more than forty years ago. I’ve pretty much forgotten everyone from eighth grade except for Sara. She is now my best friend.

Name Withheld

It’s awkward being a vegetarian in the South, where food is often cooked in bacon grease, if not wrapped entirely in bacon. At Thanksgiving I am accosted by my aunt Fae, who peers through her reading glasses at my plate, then tilts her chin down so far it almost touches her shirt as she exclaims, “Now, honey, you’ve forgotten to get some turkey.” Judging by the look on her face, she’s worried I’ve gone insane.

“I don’t eat turkey, Aunt Fae,” I respond quietly. “I’m a vegetarian.”

Horrified, she leans back, as if afraid to get too close to me. “That’s just not American.”

For the next two hours I am beset by almost every member of my extended family, each with his or her own specific concerns. Cousin Ann is convinced I’m going to drop dead of malnutrition. Judy is sure I won’t be able to get enough protein. Uncle Wayne asks, “You ain’t one of them libtards, are you?” Great-Uncle Bo has the final word: “That’s just not Christian, son,” he says. “You know Jesus ate meat.”

Brandon Giffin

Pelham, Alabama

When my brother and I started attending Catholic school in Los Angeles, it was a shock to us that all the other students were white. We had just moved from New Orleans, where we hadn’t known any white people. My brother was in fourth grade, and I was in fifth. During my first recess, none of the other girls talked to me. I sat by myself until the bell rang. At lunchtime I ate alone.

After school I saw my brother get into a fight on the street corner. I ran to see if he needed me, but he was pounding a kid who had called him the N-word. The police came and stopped it and made the boys shake hands.

The other boy remained my brother’s friend for years thereafter.

The next day, alone again at lunch, I decided that boys aren’t as mean as girls.

Terry Dicks

Los Angeles, California

I was a graduate student at Yale Divinity School when the psychosis struck. First I thought I was the Old Testament prophet Ezekiel, and then Mary Magdalene, and finally the Second Coming of Jesus Christ. I was receiving “revelations” by the second, convinced that the coincidences that seemed to follow me around were signs that the Kingdom of God was imminent.

I was in a small hermeneutics class, where we discussed critical literary theory and how to interpret texts. Besides me, there were five male students and one male professor. I was the only woman. When it was time to choose a topic for my final paper, I decided to write about the philosophy of deconstruction, which posits that texts can have multiple meanings far beyond what an author intended. I was the only one in class to love what this philosophy stood for, not just in academia but in life. For two weeks I pulled all-nighters studying deconstruction until the universe began to unravel before my eyes and everything became a matter of subjective interpretation.

By the last day of class, when I presented my paper, I was fully psychotic. The five men in the class argued against me, defending more-conventional notions of interpretation and ways of seeing the world, but I stood my ground. I was, after all, God incarnate. (This was right before my hospitalization.)

In the middle of our discussion I told my classmates, “I know your true names.” Burning with righteousness, I pointed to each one: “You are Moses, Abraham, Isaiah, Adam, and Noah.” They looked confused and concerned. As I left the building, the bluffs outside were on fire with light. I was just a psychotic woman trying to defend herself from convention, but I thought I was the Chosen One.

Rebekah Gelinas

Appleton, Wisconsin

Dinner at my house usually started with Mom calling for Dad, who was often downstairs working on some vague, never-to-be-completed “project.”

“Russell!” she would shout again and again, louder each time. It seemed obvious to me, at the age of twelve, that Dad didn’t want to eat with us. I didn’t want to be at the dinner table with my family either.

When Mom wasn’t looking, I would steal off to the basement, stepping lightly so the wooden stairs wouldn’t creak and signal my loyalty to Dad. In his workshop I would let him know that dinner was ready and Mom was pretty upset — as if he hadn’t heard her bellowing from the kitchen; as if he didn’t understand what all her yelling meant. I desperately wanted him to come eat with us and be a part of our family.

Eventually he would join us at the table, but he never really joined us. He was always distant, like an anthropologist observing customs in a foreign country. Night after night, over spaghetti with tomato sauce from a jar or chicken baked with mushroom soup over noodles, he studied us earnestly as his fork moved back and forth between plate and mouth.

I was doing my own fieldwork, trying to help my parents learn to speak the same language.

Kirsten Lundeberg

Fairfax, Virginia

My college-freshman orientation was dominated by one topic: sex. I sat through skits, group activities, and information sessions about consent, STDs, the effect of alcohol on the libido, and so on. To ensure we had access to contraception, the college made condoms available throughout campus — a constant reminder of all the sex I wasn’t having.

During my four years of study, the administration persisted in assuming every student was sexually active. I can understand their desire to promote safe sex and create a positive and inclusive atmosphere, but the barrage made me feel like the only person in the world who wasn’t doing it.

Though most of my friends had also entered college as virgins, one by one they joined the club of experienced women. They knew things I didn’t know, had secrets I wasn’t privy to. I developed many consuming crushes but remained invisible to the guys I longed for. Every weekend I went home from parties alone. I admitted my shame to almost no one, not even my closest friends. Whenever the topic of sex came up, I tried to play it cool, but I obsessed over this shortcoming, wondering what it was that made me so undesirable.

Today, nearly a decade after graduation, I know that my friends’ early sexual experiences were mostly awkward and unsatisfying. Some were even unwanted. I find myself grateful for my involuntary virginity. I wish I could go back and tell my younger self not to worry, that I wasn’t as undesirable as I believed. My time would come. Eventually.

Carmella Guiol

Cartagena de Indias

Colombia

I grew up moving from foster home to foster home, then later from one group home to the next. I was fortunate to make friends in all those places, but I was never a part of any tight-knit circle, never anyone’s best friend.

Then came prison. Behind these walls, where I’ve lived for more than thirteen years, finding friends is hard but not impossible. Most inmates stick with others of the same race. They develop a strong bond because they have each other’s backs. Though I’m white, I don’t fit in with those white people. The majority of my friends are Latino, black, or Native American.

A little while ago, after ten-plus years, a few of these fellow convicts adopted me into their inner circle. It was comforting to be welcomed into the group. We got high together, laughed together, and played together. They told me many personal stories, and I disclosed difficult parts of my life to them.

But there is a part of my life that I kept hidden, because I knew it would cause friction between us. Last month, after decades of denying who I truly am, I told this close-knit circle of mine, these men who have shed blood and tears with me, that I’m gay. They immediately banished me from the group.

Sean McCarthy

Avenal, California

When I arrived in San Francisco from Trinidad in August 1969, I was thirteen years old. My mother had spent years working hard in the U.S. to prepare a better life for my sister and me while we lived with distant relatives in Trinidad. Now her labor and prayers had paid off.

My mother could not allow her girls to wear pants to school. Only tramps did that! She sewed late into the night so that we would have dresses and skirts that fell below our knees and shirts that buttoned up to the collar. She was an excellent seamstress, but these outfits drew only ridicule.

During my first week of school my purse was stolen. When I recovered it from a garbage can, not only the money was gone, but also the photos of friends and family I had left behind in Trinidad. What value did pictures of strangers have to a thief? The reality of this new life was beginning to set in: I had to either learn to adapt or lower my expectations that it would get better.

I tried to remain unnoticeable in this somewhat hostile environment. I must not have made enough of an effort. One day the girl seated in front of me turned and asked, “How come you talk so funny?” She was referring to my heavy Trinidadian accent.

“I don’t know,” I replied. “You sound funny to me, too.”

I’m not sure what possessed me to be so bold to a notorious bully. She immediately threatened to kick my ass and told me to meet her after school the next day at Rossi Park. I’d heard rumors of the fights that took place there. If someone had messed with me in Trinidad, my older sister would tell that person to leave me alone. But now she went to a different school.

The next day the bully came prepared. In class she turned around at her desk and showed me a claw hammer in her purse. I had heard about chains and knives being used in fights, but never a hammer.

“You ready?” she said.

The only response I could muster was pitiful tears. (At least I didn’t pee myself, which is what I felt like doing when I saw the hammer.)

“Why you crying? You don’t want to fight?”

I shook my head no.

“You scared?”

I nodded. The whole class was staring.

The bully had a heart. Or maybe the satisfaction of seeing me afraid was revenge enough. She said she wasn’t going to kick my ass. Then she turned back around and left me to my embarrassment.

My greatest disappointment during those years was the fact that the kids who looked like me thought I was full of myself and treated me as if I believed I was better than they were. Few of them took the time to get to know me. It was mostly the white children and some Asians who allowed me to sit with them during lunch and at recess, who walked home with me after school, and who picked me for sports teams. They thought my accent was cool. They were interested in my stories of life back in Trinidad. It was this small measure of peace that allowed me to thrive.

K.C.

San Francisco, California

On our second date my boyfriend told me he was donating his sperm to a friend and her wife so they could conceive a child. I gave him a hug and a kiss and told him I respected his decision. In that moment I admired him for it. Looking back, I think my feelings were clouded by love and passion. That would change.

One night we met the other couple for dinner. The would-be mother (they were still trying to conceive) mentioned that she should put on bug spray to ensure she did not contract the Zika virus. I felt a shift in my feelings about this arrangement. I was jealous.

During dinner it was difficult for me to hide my emotions from the others. I didn’t know these women, I realized. I still didn’t really know the man sitting beside me, either, and I was unsure how he would react if I told him how I felt: as if I were in competition with these women.

Had they already been pregnant when I’d met him, I think I would have found it easier to deal with the arrangement. But they were still trying. With each failed attempt I was relieved but also annoyed. I remember telling my boyfriend, “We just need them to get pregnant.” What I meant was I needed the process to go quicker, because I wasn’t feeling right about it.

I finally said what I needed to say: I hated the thought that our first child would not be his first child.

In the months that followed, he and I talked endlessly about how to move forward. He eventually agreed not to go through with it.

As I’d expected, I felt guilty: for potentially preventing these women from having a child; for asking my partner not to fulfill a commitment he’d made before he met me; for having the audacity to step into their group and change everything.

E.J.

New York, New York

Unlike most kids with disabilities in the 1960s, I went to a regular school. My crutch and the braces on my feet didn’t keep me from classroom activities, but during physical education I read alone in the library. At recess I was always the one turning the jump rope, never the one jumping.

Each year in early spring I started to cross off the calendar days until I would leave for summer camp. Operated by the National Society for Crippled Children, Camp Chehalis was the one place I fit in.

When the bus stopped beside the flagpole in the middle of the grassy quad, shouts of delight filled the air. Suitcases and duffel bags were strewn across the grass beside walkers, wheelchairs, crutches, and canes.

There were campfires, singing, crafts, swimming. I had proudly earned my swimming badge and was trusted to teach younger kids how to float. At the age of twelve I had my first boyfriend, Herbie, a sandy-haired, blue-eyed boy with a leg brace who played James Bond in our theatrical parody Boldfinger. The femme fatale was a young actress with dark curls and a paralyzed left arm and leg. The villain was a small albino boy who wore a bejeweled black cape and carried a rubber sword. I was the director, galloping around on my crutch, telling everybody what to do.

A favorite after-dark activity was the Raid, an event that involved underwear and the flagpole. The mastermind behind it was Tim, who deployed his troops from a wheelchair, sending in the more-agile campers with instructions on what to grab and how to string it up before the counselors found out.

I went to the same schools as my brother and sister, but I never once wanted to go to their camp. Mine was an oasis from the world. We still had our crutches or braces or wheelchairs. We still needed help sometimes. But nobody ever asked, “What’s wrong with you?” We were never left out.

Katherine Clarke

Marlborough, New Hampshire