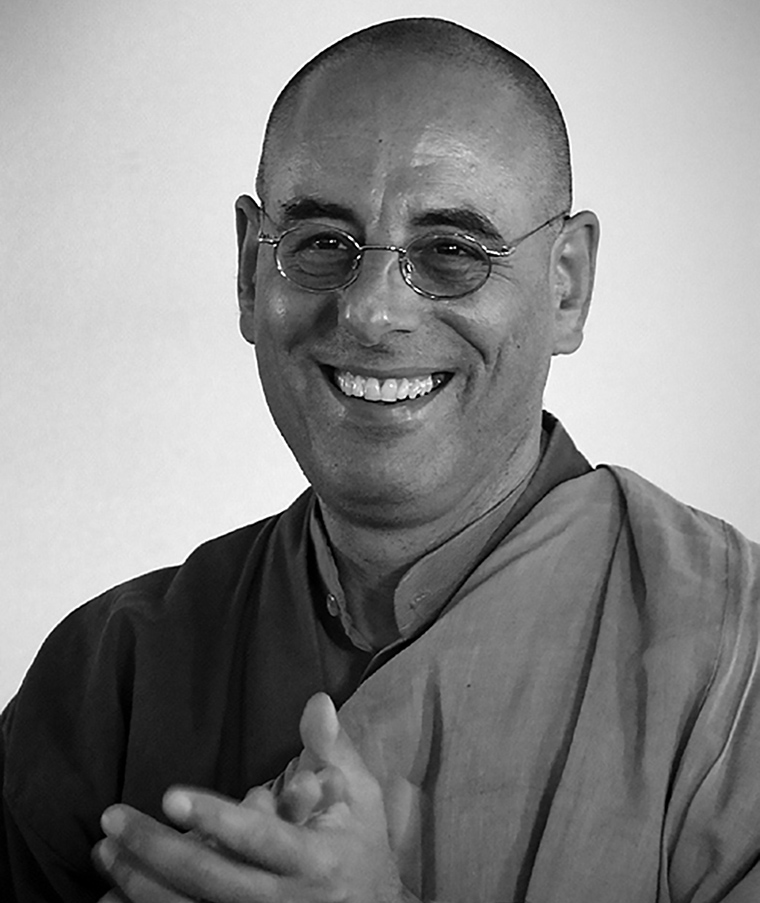

Zen teacher Norman Fischer was born in Pennsylvania in 1946 to observant Jewish parents. As a child he prayed regularly. He became obsessed with death after his grandfather died, and the experience led him to study philosophy and religion in college, where he discovered Zen Buddhism. It was the 1960s, and Zen was “in the air,” he says. He viewed it as “existentialism without the angst.”

After graduating from Colgate University in New York State, Fischer attended the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop, but he was dissatisfied with everything he wrote. Hearing that you could study Zen in San Francisco, he left for the West Coast as soon as he had earned his MFA. “I thought I’d learn how to meditate and do that on my own until I became enlightened,” he says, “just like in the books. I didn’t like gurus and Zen masters. I didn’t think I needed them. . . . I never wanted to become a Zen priest — God forbid!”

He lived a hermit-like existence in Northern California for a few years, meditating, backpacking, writing, and working odd jobs. He found that Zen helped him let go of his ambition to be a great writer and just write from the present moment. He got married, and he and his wife, Kathie, lived in a remote Buddhist monastery with their twin boys. Fischer went back to school at the Graduate Theological Union at the University of California, Berkeley, to get a master’s in the history and phenomenology of religion. In 1980 he and Kathie were both ordained as Zen priests, and the couple moved to Green Gulch Farm Zen Center, in Marin County, California, where they stayed for many years. In 1995 Fischer became an abbot at the San Francisco Zen Center, the largest Zen organization in the West. Five years later he left to start the Everyday Zen Foundation, and he continues to serve as senior dharma teacher there. He also leads conferences and has taught Buddhist practices to groups ranging from Army chaplains to Google engineers.

Fischer still considers himself a member of the Jewish faith, and in 2000 he helped found a Jewish meditation center, Makor Or, in San Francisco. He also published a “Buddhist” translation of the Hebrew Psalms, titled Opening to You. He is the author of nineteen books of poetry, most recently On a Train at Night and Untitled Series: Life as It Is. He has written eight books on Zen, including Training in Compassion and What Is Zen? Plain Talk for a Beginner’s Mind, cowritten with Susan Moon. His latest, The World Could Be Otherwise: Imagination and the Bodhisattva Path, will be released in April 2019 (normanfischer.org). He and Kathie now live a mile and a half from Green Gulch Farm, in Muir Beach, California.

I first met Fischer thirty-six years ago when Traveling Jewish Theatre, which I cofounded, moved to San Francisco. Our group was unofficially adopted by the San Francisco Zen Center, and I began narrating the center’s annual Buddha’s-birthday pageant, a humorous and eloquent play Fischer had written. But it wasn’t until 2012 that I finally experienced Fischer as a teacher, during a daylong meditation retreat. His style was wise, humble, and funny, and I’ve since read most of his books, listened to his recorded talks on the Everyday Zen Foundation website (everydayzen.org), and sought his counsel on occasion. Though Fischer has joked that, as Eastern European Jews who share a last name, he and I must be distantly related, we have no evidence of it. His friendship — which he seems to extend to everyone he meets — has been a particular comfort to me, especially since the 2016 presidential election.

This conversation took place in 2017. It is an edited version of a much longer interview. [Since the participants have the same last name, we’ve used their first names below. — Ed.]

NORMAN FISCHER

Corey: If you were to distill Zen Buddhism to its most basic, core concepts, what would those be?

Norman: [Laughs.] Oh, boy. Maybe the simplest and truest thing to say is that Zen doesn’t have a basic core concept. Zen is just appreciating being alive. There’s nothing to it beyond that. But if I said only that, it would be a little silly and disappointing, even though it’s true. So I will say more.

The essential point of Zen is to be fully present, fully alive in the moment, while recognizing that to be fully present is to include all the past, a concern for others, and a sense of going beyond one’s own limited sphere of identity. Zen advocates a profound sense of presence, not just “be here now,” by which I mean the commonplace idea that being present is simply forgetting about the past, not worrying about the future, and being natural and easy: “Don’t worry, be happy.” I am not against this, but I think Zen practice proposes something else. Zen teachings say there is no present moment as we usually conceive of it. What we call the present moment disappears under scrutiny. Look for it, and all you find is the past and the future. Look for those, and you don’t find them either. The so-called present moment contains everything — not only a person’s present perception and emotional experience but all experience in all times. So there is an ineffable depth to what we conventionally call the present moment. It includes life, and it includes death. It includes joy, and it includes suffering. Zen’s focus is to be present in this fuller sense of what any moment includes.

We’re so limited by our ideas, our hopes and fears, our sense of identity. We think we are someone. We like this or that; we don’t like this or that. But that’s not all we are. To be fully present, we have to go considerably beyond ourselves. It requires a powerful identity shift, a different way of situating oneself within experience. This takes lots of training and repetition and discipline.

Corey: Is this focus shared by all forms of Buddhism, or is it specific to Zen?

Norman: I would say it’s shared by all forms of Buddhism, but I think Zen cuts to the chase and pushes everything into that one idea of being fully, almost ineffably present.

Zen Buddhism is interested in awakening through different ways of looking at the world. It doesn’t try to tell you what the absolute truth is, the way Western religion does. At a certain point in history people began sincerely thinking, “Well, if you don’t believe in Jesus, your soul is in jeopardy. So we should do whatever it takes to straighten you out. That’s an act of compassion because we’re in possession of an absolute, metaphysical truth.” Forcing religion on unwilling others turned out to be a terrible idea.

Corey: Buddhism originated in India five hundred years or so before the Common Era. What new ideas was the Buddha expressing?

Norman: The Buddha’s teachings were very different from the fatalism that dominated Indian spirituality at that time. It’s often said that the Buddha was socially and politically radical. He proposed that all people, of any social class, could join the Buddhist order and, by virtue of their own conduct and cultivation of mindfulness, transcend their position in life. They could become a sage. And this went for both men and women, which was itself radical.

Corey: Is this what it means to be a bodhisattva?

Norman: A bodhisattva is someone who realizes that the only liberation possible is liberation for all, that self-liberation is not an option. A bodhisattva identifies with and extends a kind heart to all sentient beings as an expression of his or her liberation into a wider sense of identity.

Corey: What does enlightenment mean in the context of Zen practice?

Norman: I think it means a serious rejection of self-centeredness. It implies being compassionate and free from the negative emotions that self-centeredness creates: envy, jealousy, anger, loneliness, isolation. But we’re not talking about a hard-and-fast line, on the other side of which there’s total perfection. I like to use the word transformation. Buddhist practice is meant to be deeply transformative. Body, emotions, identity, thinking — it all gets transformed by practice. You feel and see things differently, and you behave differently. In the early days of Buddhist practice in the West, “enlightenment experiences” — mystical feelings of oneness or transcendence — were thought to be the goal. The idea was that you’d meditate your way to an enlightenment experience, and afterward you’d become a permanent member of the spiritual elite. People do have such experiences, but in Zen practice we don’t make a big deal out of them. They tend to occur toward the start of practice, especially if the person is in a state of crisis. Such experiences are openings, beginnings. The real focus is on transformation, not the individual experiences we might have along the way.

Corey: What about the stories in Zen literature that depict a monk or layperson becoming suddenly enlightened by something the master says?

Norman: I suppose some of those are true. I know from talking to countless contemporary practitioners that people do suddenly experience a different sense of their lives, and they never forget it. But it’s also pretty clear that those experiences are valuable mainly as encouragement. Without continued practice and cultivation, they become wonderful memories that probably won’t change you all that much. To feel the full benefits of what Zen promises, you must continue to practice every single day.

Corey: Is there a goal to Zen meditation?

Norman: Yes and no. I think you need to make a strong effort to be present, to really pay attention and let go of all thoughts and images that arise in the mind. And you probably won’t make that effort unless you have a goal. Maybe you can’t bear the state you’re in, or perhaps you just feel there’s something missing, and you hope that meditation will help. But with continued practice, that initial goal eventually falls away, and you recognize that the goal itself was a projection of your own suffering. You imagined a state free of pain, but your pain doesn’t dissolve; it transforms, and you begin to appreciate it. Your initial goal, unrealistic or mistaken though it may be, encourages you to make an effort in your practice. The practice becomes easier, less stressful, less painful. You develop a deeper appreciation for it. The goal becomes doing the practice every day.

Corey: How would you instruct someone who has never practiced meditation but wants to try it?

Norman: Find a quiet place. Make up your mind that you’re going to sit still for a predetermined amount of time — let’s say thirty minutes. Sit up straight. Pay attention to your body. Maintain an upright posture, but don’t strain yourself. Bring your attention to your breathing. Notice whatever thoughts or sensations come up and try to let them go and return your awareness to your posture and your breathing, which is the concrete feeling of your life. Let go of all other thoughts and images. Do this every day for a week or a month as an experiment and see how you feel. See what effect it has on you.

Corey: Does Zen Buddhism have a concept of God, a supreme being, or a creator?

Norman: No. There’s certainly no idea of a creator, because in Buddhism there is no creation. It’s a beginningless universe.

Corey: How do you reconcile Buddhism’s nontheism with your identity as a Jew?

Norman: They don’t seem contradictory to me. Judaism and Buddhism are different sets of ideas. I can hold scientific ideas at the same time that I hold abstract ideas about literature or philosophy, can’t I?

A textbook on religion will tell you Judaism believes the following, and Buddhism believes the following, and these beliefs don’t match. But when you talk to a learned Jewish or Buddhist mystic, these “beliefs” blow away in a moment. They’re talking about much broader concepts, and there’s a lot of overlap between them. I’ve always felt that. It’s never been a problem for me.

A cardinal principle of Judaism is that we can’t have an idea or image of God. God is bigger than anything we could have in mind. To me that seems perfectly compatible with Zen practices and philosophy.

Corey: Do Buddhists pray?

Norman: Absolutely. Some people think Buddhists don’t pray, because from a Western standpoint, if there’s no God, there’s no one to pray to. Yet if you visit a predominantly Buddhist country, you will find that Buddhists there go into temples, offer incense, make prostrations, and pray for the health or success of their loved ones or their nations, just like Christians and Muslims and Jews do.

Throughout history most people were probably quite certain that this life we are living, which lasts only a handful of decades, can’t be all there is. There must be larger forces beyond it. This belief is a great comfort. Maybe your life is tough; maybe it looks like there is no hope; but there is something loving and wise beyond it that holds and protects you, however difficult things are. To reach out to this larger force has been psychologically necessary for most people, whatever their faith. Only very recently have people felt powerful enough not to need such vague and superstitious beliefs. But maybe our contemporary veneer of confident materialism is wearing thin, and underneath we still need to feel there is something else.

Like meditation, chanting, or contemplation of spiritual texts, prayer is a practice that influences the heart and mind. It changes the way a person looks at and lives her or his life.

The Buddhist movement in the West began as an alternative to Western spirituality. It emphasized the differences between Christianity and Buddhism and tended to portray Buddhism as a sort of humanistic psychology with no supernatural content. Most Western Buddhists still see it that way. But this is not characteristic of what Buddhism has always been and still is in most of Asia.

I appreciate the “religious” or supernatural side of Buddhism. It proposes a much larger sphere of existence than the one we are capable of seeing or understanding, and it helps me to be humbly aware of my own smallness. My life comes and goes in a minute! And yet, at the same time, everything is here in the present moment where I am.

For me, prayer is when I reach out to the infinite space inside and outside myself for connection, recognition, and comfort. I pray to I-don’t-know-who-or-what, but prayer makes sense to me anyway. If I just speak when I’m alone, I feel that someone is listening. If you went alone to the middle of the desert or the top of a mountain and spoke words out loud, you might have the eerie sensation that someone is listening.

The depth of our human delusion — our separateness, our vulnerability, our alienation in the world — is not only socially conditioned; it’s also deeply ingrained in our minds, our perceptual apparatus, our language, our sense of being a person. This is the basis of our confusion and suffering. We grow up conditioned to separation, and we act on that our whole lives, compounding the problem.

Corey: What does Zen Buddhism have to say about life after death?

Norman: Zen Buddhism neither denies nor affirms a life after death, but, like all religious practice, Zen exists in a framework that’s larger than one’s life span. To really appreciate this life as it is, you have to understand that it’s bigger than your lifetime. There’s a sense of mystery about it. There’s more to it than there appears to be. At the same time, it’s heretical in Buddhism to say there’s any kind of “soul” that gets reborn from one body to the next.

Corey: So what does get reborn?

Norman: Consider the analogy of an acorn: If you plant an acorn in the ground, you will get an oak tree. But examine the oak tree, and you won’t find any piece of that acorn in it. All you can say is that there is a continuity between the acorn and the oak.

Corey: But something is reborn?

Norman: The energy of this lifetime spills over into another, but it’s not “me” as a person that continues. The person that I am is a projection, a history, a body, a set of thoughts and ideas. What I call “my body” remains in existence forever as molecules circulating. So my body actually never dies; it just opens up! Consciousness is like this. My individual, personal consciousness ceases, but the consciousness itself, which was never actually mine, continues in some way, though it’s altered by what has happened. Consciousness just rolls on and on, without beginning or end. Although there’s always rebirth, there is no “something” that is reborn.

When the Dalai Lama talks about rebirth, he does not say, “When I was the fifth Dalai Lama . . . When I was the tenth Dalai Lama . . . When I experienced that in 1647 and this in 1820 . . .” He says, “The fifth Dalai Lama said this. . . . The twelfth Dalai Lama said that. . . .” I think he is inspired by them and feels that his karma is in continuity with theirs, but I don’t think he identifies as them.

Corey: There’s a great emphasis in Zen on being present, moment to moment — no metaphysics or conceptual thinking. Yet there is also talk of transcendence. What are we transcending?

Norman: To be really present is to transcend the present, to recognize that there’s more to the present than what appears to us through our senses. It’s paradoxical. I’m not saying there’s another place that’s not here. I’m saying that what is here, what we’re perceiving, is more than we think it is.

Corey: Is that another way of saying that conventional habits of mind limit our experience?

Norman: Yes, and these habits are built into our brain. The depth of our human delusion — our separateness, our vulnerability, our alienation in the world — is not only socially conditioned; it’s also deeply ingrained in our minds, our perceptual apparatus, our language, our sense of being a person. This is the basis of our confusion and suffering. We grow up conditioned to separation, and we act on that our whole lives, compounding the problem. We can’t not be who we are, but with practice, we can eventually understand ourselves differently.

Corey: And yet these teachings about our social, psychological, and biological limits have come to us from limited human beings.

Norman: Right. We are paradoxical. We are beings who are limited and who will always create a world of suffering, and we’re beings who have the capacity to understand that and, in some way, go beyond it. We transcend our limitations through the recognition that we can’t transcend them.

Corey: Basic Buddhist meditation practices are often promoted as healthy techniques for stress reduction. Has that had an effect on Zen in North America?

Norman: I’m sure it has. In the U.S., meditation was once a very countercultural thing that only odd people would do. Now meditation is mainstream. But if fifty people try meditating, maybe only one of them will end up going to a Buddhist group. The other forty-nine will meditate once in a while at home using a book or go to a secular meditation class.

Corey: How else has Buddhism influenced Western culture?

Norman: The field of psychology has been revolutionized by Buddhism. Freud was like an archaeologist: let’s dig and discover the causes for your present neurosis, and once you’ve discovered the causes, your neurosis will clear up. But now many psychotherapies are about how to work with your mind in the present to shape your behavior in a way that is more wholesome and healthy for you. Plenty of new therapies are not about the past at all. Life coaches, too, help you work with your attitudes and your mind the way Buddhism does.

Corey: What has the process of transcending self-centeredness been like for you personally?

Norman: I spent many years training in Zen centers, trying to be less stuck on myself and more caring for others. Being able to notice others as gorgeous and sympathetic creatures — this is liberation from the tyranny of the self: self-judgment, self-protection, self-distortion, self-limitation. Seeing that you are more than yourself reduces your pain and suffering. I practice every day because I continually need to be reminded of this. The implicit goal of all Zen practice is the taming of the self and opening to the other. This is the effect the practice has on you if you do it with commitment.

Zen also involves shaping your conduct to be less selfish: speaking kindly, practicing generosity and compassion, and so on. This kind of practice has become more important to me in the past several decades.

Corey: How has politics intersected with your role as a Zen teacher since the 2016 presidential election?

Norman: There’s a political dimension to Zen practice, because when you are concerned about others, you want the world to be better for all people. You want our political leaders to create a fairer world, and also a more sustainable world. If you care about life, you care about climate change and carbon emissions. You want to support politicians who understand the immensity of the problem and strive to reverse it. Taking care of people in need should be an imperative for any religious practitioner. Most of the policies of the Trump administration are not compatible with compassion for people in need or for other forms of life. This is an urgent situation in which we have to be political as part of our religious commitment.

I think progressives have made a big mistake in not recognizing the importance of religion to many people. The Republicans realized that a lot of Christian voters were feeling marginalized and disrespected by the Left, and Republicans went to those religious Christians and said, “We respect you. We love you,” and brought them into the Republican and conservative fold.

Trump has bad policies that should be opposed, but that opposition is not incompatible with being compassionate toward him. Now, it’s not like I’m sitting here worried about poor Donald Trump or taking special time to cultivate love for him. But I don’t hate him. I am amused by him in some ways. I can appreciate his chutzpah. I assume that, like any human being, he has some kind of inner life — though he seems to be quite out of touch with it. But I don’t agree with most of his policies; I oppose them. And I don’t think his public style is helping the country. In fact, it is hurting people. It is weakening the social institutions that make democracy possible.

We have to get over being dismayed by other people and consider what they’re saying. No denigration or demonizing of others. Maintain a calm but critical exploration of views, not just an outraged dismissal. Be respectful, and don’t be pious.

There’s no reason to be in despair, as far as I can see. Life is always hopeful. Wherever there’s life, there’s also possibility.

Corey: Hope implies a future. . . .

Norman: The present implies a future! [Laughter.] Wherever there’s a present moment, embedded in that present moment is a future moment. As soon as that’s no longer the case, you’re dead. Living means there’s a future. And a future means anything could happen. If you want to say only bad things will happen, go ahead. Be my guest. But that’s not an obvious conclusion. The obvious conclusion is that anything can happen.

Corey: Have years of immersion in Buddhism helped you avoid demonizing those you don’t agree with?

Norman: Yes. To accomplish this, I have to be truly nonaggressive. I can’t just pretend to be nonaggressive; I actually have to be nonaggressive. To pretend to be nonaggressive as a political strategy doesn’t work.

Corey: Why not?

Norman: If you are only pretending to listen or to care, if you are being polite only to advance your agenda, then your motivation will be transparent, and you’ll get creamed. It won’t take long before you abandon that strategy and come back with even more aggression than you had before, because now you are pissed off that your nice-guy strategy was taken advantage of.

Actual nonaggression, as opposed to strategic nonaggression, is something else. As a spiritual practitioner you are more committed to caring for others than you are to a side or a cause. Caring for others doesn’t mean caring only for the ones you are sympathetic to; it means all others. If it’s only some, then you’re going to end up being aggressive toward the others who seem to behave unjustly toward the ones you care about. And aggression breeds aggression. You might win with aggression, but there is always backlash, and pretty soon you lose. I have seen this many times. I am convinced that only real, heartfelt nonaggression works in the long run. And this isn’t something you can just decide you are going to feel. It is challenging to be genuinely caring and loving. It takes spiritual work, psychological work, meditation, cultivation. But there is no doubt that, for me, this is the only way.

I have practiced Zen enough to recognize when I get agitated and start blaming someone for the state of the world, and I reject such thoughts. It doesn’t take me long to see through them.

Corey: Has anyone in U.S. public life, in recent decades, embodied these Buddhist values?

Norman: I thought Obama was great. Let’s remember that he won two strong victories. A black person getting elected president twice in the United States? That happened because his feelings of concern for others — of caring and fairness and not demonizing the other — seemed genuine, and I believe they are genuine. Obama is a decent human being, an exceptional human being. Whatever resentment there was against him was not nearly enough to overcome that. I loved Obama even though he did a lot of things that I wish he hadn’t and failed to do some things I wish he had. But I always attributed that to the situation rather than to his preferences.

Corey: Let’s talk for a moment about your writing. Zen uses language in paradoxical ways. What is your own relationship to language as a writer, and how does that connect with your practice?

Norman: Writing is a primary activity for me. I was doing it before I began practicing Zen. At the same time, I’ve always been suspicious of language and frustrated by it. Language is so limited. It makes our world so small. [Thirteenth-century Japanese Buddhist priest] Dōgen said, more or less, that language is creating a false world, but the only way out of that false world is through language. That’s the subject of all my poems: the attempt, which always fails, to go beyond language through language.

Corey: How does it feel to always fail?

Norman: It’s frustrating. [Laughs.] I’m aware that writing poetry is a supreme waste of time, yet it’s totally essential. I have to write poetry, however useless it may be. Its uselessness seems to be its chief virtue.

I remember as a little boy feeling the need to respond to the sense of strangeness or ineffability I experienced. I still write from that same feeling. It goes beyond self-expression. Spirituality and art, to me, are the same impulse. Both are trying to go beyond the surface and find a deeper reality behind the world as we know it. Religious people and artists are visionaries. Sometimes they don’t understand their own vision, but it is compelling to them. They can’t shake it or ignore it.

I’m aware that writing poetry is a supreme waste of time, yet it’s totally essential. I have to write poetry, however useless it may be. Its uselessness seems to be its chief virtue.

Corey: Did your writing change when you began Buddhist practice?

Norman: Yes. Before I started practicing, I was having a hard time writing. I was not happy. I didn’t think I was writing anything good. I was constricted and getting in my own way. Practicing Zen opened me up. It gave me a sense of freedom and allowed me to write with joy. The process of sitting meditation helped me see that it didn’t matter how successful or unsuccessful I was. It opened up my thinking. Having confidence in the present moment during sitting meditation gave me confidence in the present moment while writing.

Corey: I remember you saying right after the 2016 presidential election that it’s important to read novels, listen to live music, and hang out with friends as forms of resistance.

Norman: I didn’t mean it as resistance to Republicans or even to Trump, but as resistance to the soul-killing way of life that we have collectively established. How many times have we been disappointed? How many times have we said, Let’s get rid of this politician, and then been bitterly disappointed in the next? It’s a bigger question than who we vote in or out of office. We should have amazing people run for office in 2018, and we should vote out a lot of people currently in Congress. That’s important. And yet real change is not about any one of those people. It’s got to be a collective, from-the-bottom-up feeling of resistance to the soulless world we live in. We have to say, No, we don’t want a world like this anymore. We want it to be different. So let’s elect good people but not depend on any one person.

Corey: What do you mean when you say our world is soulless?

Norman: Thanks for getting me to take a deep breath! Maybe I am being too one-sided. The world is great. This country is great. The skylines of San Francisco and New York are beautiful to behold, especially on a sunny day. My smartphone is amazing. The world we have created is a wonder, and I am personally taking full advantage of it.

But, at the same time, we are in a mess. The impulse to make money has left us with tremendous injustice. Some people are doing great while others are suffering terribly. We are screwing up the climate, causing extinctions, causing the earth to reorganize herself in ways that will probably ruin a lot of what we have built and maybe even make the planet uninhabitable for us. Our creativity has also caused us to produce weapons capable of killing huge numbers of people. The chances of our never having a nuclear war are slim. And I haven’t even mentioned drug addiction and mental disorders and racism and sexism and abuse, most of it more or less caused by our high-pressure, runaway consumerist society, where even the most privileged people are a wreck. We don’t have enough depth, meaning, humility, kindness, love, or respect for the other and the unknown.

Corey: It seems to me that talk of resistance and the need for change is an expression of preference. What about the Zen ideal of letting go of preferences?

Norman: The Buddhist teaching about preference is subtle. There is no way not to have preferences. They are basic to the process of consciousness: you will be disgusted by some things and attracted to others. The question is how not to let preference push you around, to be able to choose whether to be motivated by a preference or not. I would like to have my preference satisfied, of course, and if I can adjust things to suit my preference, and it is reasonable to do so, good. Let me do that. But I also want to be OK, rather than miserable, when it is not satisfied.

In Zen practice we follow precepts, which we understand not as rules to live by but as a way to be fully present in a complicated world. The precepts more or less amount to being content with what is, not making things worse, and not hurting anyone. Following these precepts ideally becomes a more primary impulse than preference — or maybe it becomes the main preference. In my own case, I enjoy what I do and am trying to be of benefit to others. I hope things turn out well, and I work toward that end, but if they don’t, I am OK with that, too. Because then I find myself in a new situation, one that I didn’t want but one I now have to embrace. That’s what the teachings are telling us: Where your preferences are ethical and significant, act on them, and then embrace whatever happens, even if your preference is not realized. Act, and then let go. Act, let go. That’s what we have to do.