In the early 1980s, when I lived in Austin, Texas, I met a woman named Anne and a man named Mark. She was my good friend, and he was her boyfriend, and they hardly needed me to complicate their delicate situation, but they got me anyway.

For many years afterward I avoided thinking about them, and when I finally did — first tentatively, then obsessively — big chunks of the story seemed to be missing. I went back and checked my date book from that year. Scribbled among the feminist quotations were lists and appointments, plans to see concerts, names of forgotten movies. On Saturday, January 17, an entry reads, “Dinner with Anne.” Sideways in the margin of a week in April are the ingredients for Anne’s black-bean recipe, set down in her elongated, slightly whimsical handwriting: “black beans, basil, garlic, oregano, onion, comino, Pace’s, mustard, molasses.” There are a few hexagrams from the I Ching copied down along the way, sometimes accompanied by lines of advice: “It furthers one to cross the great water.”

In May there are just two words: “Leave Austin.”

In an effort to dredge up my memories of that time, I whisked off a jaunty letter to Anne, my first communication with her in about twenty years.

It seems she was surprised to hear from me. “Marion,” she wrote back a week later, “I kinda liked you when I met you, and then I learned to love you, but now you’re just the skank that fucked my man when I was struggling to make a family.”

As soon as I could gather my thoughts, I sent her a reply saying how unsettled I was by her response, how I didn’t think we had left things this way. She answered again, still angry, and again I wrote back.

I knew Anne wouldn’t keep answering me if she didn’t want to resume our friendship. I was right. In her next letter she set aside her grievances and agreed to send me some of her journal entries from that time. She also agreed to come visit me in Baltimore. Her journal entries were more forgiving than angry, more accepting than outraged. She seemed grateful for our friendship and wrote about how lonely she had been before she’d met me. She also acknowledged that when she had been my age, she, too, had been careless with other people’s feelings. She had not yet realized, as she put it, “how lonely most people are and how tenderly they must be treated.”

I ’d first met Anne when she was hired to help me at the Texas Natural Resources Reporter, a regulatory reference guide for the legal representatives of the big polluters who were destroying the coastline. I was pretty good at writing ad copy and harassing people to renew their subscriptions, but I regularly screwed up the mechanical parts of my job — such as paste-up, xeroxing, and collating — to the great irritation of my coworkers, not to mention our boss.

Lots of interesting people interviewed for the job of saving my ass, including Anne, a graphic artist and painter who roared up in a vintage red Volvo. She was twenty-nine, which seemed a lot older than my twenty-two. With her long, curly hair and wide-set gray-blue eyes, she looked something like the singer Janis Joplin, though prettier and less squinty. Like Janis, she never wore a bra or makeup and had a proclivity for frankness in all things. She smoked unfiltered Camels and drank Scotch neat.

After she was hired, she took over paste-up, and from then on the columns were symmetrical and the page numbers consecutive. She would come in at night to use our gigantic, noisy photocopier to xerox and collate the three hundred sets of replacement pages we sent out every month. That machine and the sleek IBM Selectric typewriter in our office — and the prospect of long nights alone with them to work on her journals, plays, and artwork — were what made this bad job seem like a good deal to Anne. She preferred to work nights anyway, because it gave her time during the day with her baby girl, an eighteen-month-old named Rose. Anne was the first friend I’d had who was a mother.

There we were, just the two of us in that sterile, windowless office or outside in the parking lot smoking and watching people. Anne had a musical voice, a Southern accent, and a history I loved to hear about, though parts of it were so painful she avoided talking about them. Her mother, Ruby, was a lounge singer and party girl who had abandoned her husband and five children when Anne was nine to run away to the big city and pursue her career.

I pictured a girl with pigtails walking into the house after school, lunch box in hand. Mom? No answer. Mom?

I told her about my family, too: my mother the golf champion; my father the workaholic; the whole wisecracking clan, shouting witticisms at one another over the Sunday Times.

Anne had had some affairs with women, and this impressed me, but she had something else that intrigued me even more: Mark. At that point in my life all you had to do was put a deeply depressed, closed-off guy in my path, and my antennae would start twitching. If he were also attractive and talented and seemed to light up just a little at the sight of me, I might soon become so interested, so hooked, so filled with lust that I’d hardly be able to see anything else.

I remember first meeting Mark at a gathering he and Anne had after the murder of John Lennon in December 1980. Lennon’s death was a tragedy felt worldwide, and many of the inhabitants of Austin — freethinking potheads, latter-day flower children, slacker musicians, long-haired grant writers, and guitar-playing lawyers — were on the front lines of the bereaved. Coming as it did just a month after the election of Ronald Reagan, Lennon’s passing seemed to many the end of an era.

I found Anne and her friends in the kitchen, smoking joints and drinking wine; the radio’s daylong tribute played Beatles songs in the background: “I read the news today, oh boy.” Anne fondled the massive head of her Great Dane, Jude.

We were talking when Mark came into the room. Who has an extra cigarette? he said, pushing his hair out of his face with one hand, holding their blond baby on his hip with the other. I looked up to offer my pack and took in his compact form, his thin white T-shirt. Anne had told me that he was a mime and a clown, and you could see from his smooth, elastic face and body, his pale skin and dark eyes, that he would be perfect for both.

He walked toward me with an ironic smile, and I gave him one of my Merits. His face was close as he bent over the match I lit, and he flicked his gaze from the tip of his cigarette into my eyes.

Someone asked whether Mark’s clown troupe, the Great Nodotties, would be doing their scheduled gig that week, and he sighed. The show must go on, he intoned gloomily.

I watched the three of them together as the night wore on: Anne’s steady gray eyes on Mark’s face; their tender attentions to Rose; later, his hands beneath Anne’s hair, unknotting her neck and shoulders.

One of the clearest images I retain from that night is of Mark bending over to take a mason jar full of gleaming jalapeños out of a small white refrigerator. He plucked them from their green juice, laid them in a line on a cutting board, and sliced them with a knife. My mouth was watering.

Even during the twenty years when I hardly thought of Mark and Anne, I still whispered his name in my head every time I put a jalapeño on a tuna-fish sandwich, as he’d taught me.

I lived in a bungalow on the edge of downtown. The population of my household was constantly in flux, with new people always arriving. Domestic life at our house was governed by a fierce combination of politics and penury. We eschewed paper products and passed a bandanna around the table as a communal napkin. We took turns grocery shopping and cooking. Few among us had the patience required to prep vegetables: it was common to find hunks of onion and squash as big as a toddler’s shoe in your stir-fry.

Yet despite the beloved eccentricities of my living situation and the general excellence of life in Austin, I had other plans. I was going to stay until my chapbook of poetry was published that spring — I had won a contest sponsored by a small press in the nearby town of New Braunfels — and then I was moving with my sister and my best friend to New York City, where I was going to enroll in graduate school and get an MFA. As the writer of such poetic works as “Sunbathing at the North Pole” and “The Tampon Poem,” I had outgrown Austin and its provincial poetry scene. New York was a much more appropriate setting for the fabulous literary career that awaited me.

As soon as I saw the Great Nodotties perform, I wanted to join them. After the show I found the troupe packing up. Mark had taken off his whiteface, and his hair was wet; he shook his head like a puppy and rubbed his eyes. In makeup or not, his brown eyes drew my attention.

He and the others were enthusiastic about the idea of my performing with them. We planned for me to come to some of their rehearsals and make my debut on Valentine’s Day.

There was another regular gig I attended with Anne in those months: one of her good friends was a well-known local musician, and he appeared frequently at a popular venue called the Hole in the Wall.

Anne’s friend was a volcano of a man whose mountainous exterior concealed a molten mass of anger and arrogance. His preternaturally deep bass voice made him a seductive presence on his weekly radio show. He was a virtuoso guitar player, and his songs combined Afro-Cuban melodies with lyrics that ranged from political outcries to tender love songs. His main source of income was not making music, however, but selling abundant quantities of weed. Anne never was able to explain to me why she liked him so much. Maybe it was because he was an outlaw-musician type, or maybe it was because he was such a misanthrope that if he was nice to you at all, you felt special.

Anne had been romantically involved with this musician in the past, during his first marriage, and he’d tormented her with his bizarre concept of marital fidelity, according to which it was fine to write love songs for Anne, fine to make out with Anne between sets, and even fine to lie with Anne in her bed till sunrise, as long as they didn’t actually Do It. So they didn’t, technically.

Now he was in a fairly recent second marriage, but I noticed when he called Anne at work, she took his calls with the door closed.

I was a regular at Spellman’s poetry open mike on Thursdays. Though these performances were something anyone could sign up for and were really no big deal, I thought of them as an early but indispensable phase of my campaign to build a following and become a national poetry phenomenon. I dressed for my appearances in various getups: a fedora pulled low over my eyes and a black bustier, or an ice-hockey uniform complete with pads and helmet. I often got nervous before the show and prepared with a few swigs of booze, sometimes taking a drink with me onstage, and maybe a cigarette, too.

For my debut appearance with the Nodotties, I had planned a performance titled “Let’s Go to Bed with Marion Winik on Valentine’s Day.” Dressed in red flannel pajamas and lying on a folding lounge chair, I would read poems about men and relationships. I would be sexy and heartbreaking and funny and profound, and my work would be a guided tour of attraction, passion, obsession, rage, stupidity, and loneliness — or so said the posters I plastered all over town.

Unfortunately I forgot the words to the poems I’d thought I knew by heart and couldn’t find the poems I had typed up. I shuffled through piles of paper, spilling them on the floor, stopping and starting and stopping again when I realized I had the wrong poem. Thanks to my hundreds of xeroxed flyers, my housemates were there. People from work were there. Buck from the boot-repair shop was there. Mark was there, of course, and Anne, though she left early to go to the Hole in the Wall: the weed-dealing local musician had a show.

Anne always said he was just a friend, but the way she acted about him was not friend-like. She became light and girlish when she talked to him or was going to see him. I knew that he often met her in the park when she walked Jude, and I noticed how regularly that dog needed to be walked.

Sometimes Anne left Rose with their housemate Susie when she went to the park; sometimes she left Rose with her daddy and me. My friendship with Mark deepened.

Though Anne was not completely candid with me at first, I soon realized she was in love with the musician. Aside from the fact that he was married, she was with Mark, and they had Rose. And anyone could see Mark knew. What the hell was she thinking?

But after further consideration, I began to view the whole thing differently. Whatever was going on, it was something she needed. And if she didn’t want Mark and had somebody else, then maybe that was OK.

A few weeks after Valentine’s Day I was in the kitchen with Mark, looking at the funny drawings in his sketchbook, inhaling his scent of Dr. Bronner’s peppermint soap laced with boy sweat and a whiff of pot. Our legs were touching under the table.

How did you get your clown name, Olo? I asked him.

Look at this, he said. He got a pen and wrote olo. It’s a cock and balls, see?

My mouth dropped open. I grabbed the pen and drew eyes and a nose, and he said, Right, I see with my dick. We laughed like teenagers, and then he reached into the fridge to get the jalapeños so we could eat half a jar of them with tuna fish.

In March Anne, Mark, and I made a plan to visit Driftwood, Texas, where the printer of my book of poems lived. We were going to take a tepee and sleep in it for a couple of nights. When we got there, Mark and Anne weren’t getting along, and I wasn’t helping to defuse the tension. In fact, I was smoldering like a fire, sending my own little smoke signal out the roof of the tepee.

Anne drove back to Austin one afternoon to do an errand and left us there, watching Rose. Mark, sounding bitter and discouraged, told me he felt alone all the time now. He wanted to get some drugs and asked me if I had any ideas.

I have an idea, I said.

What?

Nothing.

Really, what?

He knew what I was thinking, and all I had to do was say it. But I didn’t.

That night, after Anne came back, it was hard to fall asleep. I was uncomfortably aware of their bodies next to mine in the tepee. When I finally fell asleep, I dreamed that they were making love and then that we were all making love, and then I woke up, staring into the blackness.

Anne must have slept poorly, too; in the morning she was exhausted and sick of us. She told us if we were thinking of becoming lovers, we should just go ahead with it. These things can work, she said, if people are discreet and considerate.

That is how I remembered it: that she had given her permission; that she had seen what was coming more clearly than we had. But years later, when I finally saw her again in Baltimore, she asked: Where was the discreet and considerate part, my dear?

Good question.

A few days after we got back from Driftwood, I gave Mark a ride home from the Nodotties show. We’d both been talkative earlier in the evening, but in the car we were silent. We pulled into their driveway, tires crunching on the gravel. The house was dark. He reached over and turned off the engine. I swiveled toward him, and we started kissing hard. It was our first kiss, but there was no gentle prelude or subtle exploration.

Finally I had my hands in his hair. Finally my fingers traced the bones of the face and throat I had studied so many times. Finally his hands were on me, under my shirt, on my back, dragging me toward him. I hopped over the gearshift and straddled him.

The ’78 Subaru station wagon was not a roomy car, so he opened the door on the passenger side, and we rolled out into the driveway in the moonlight.

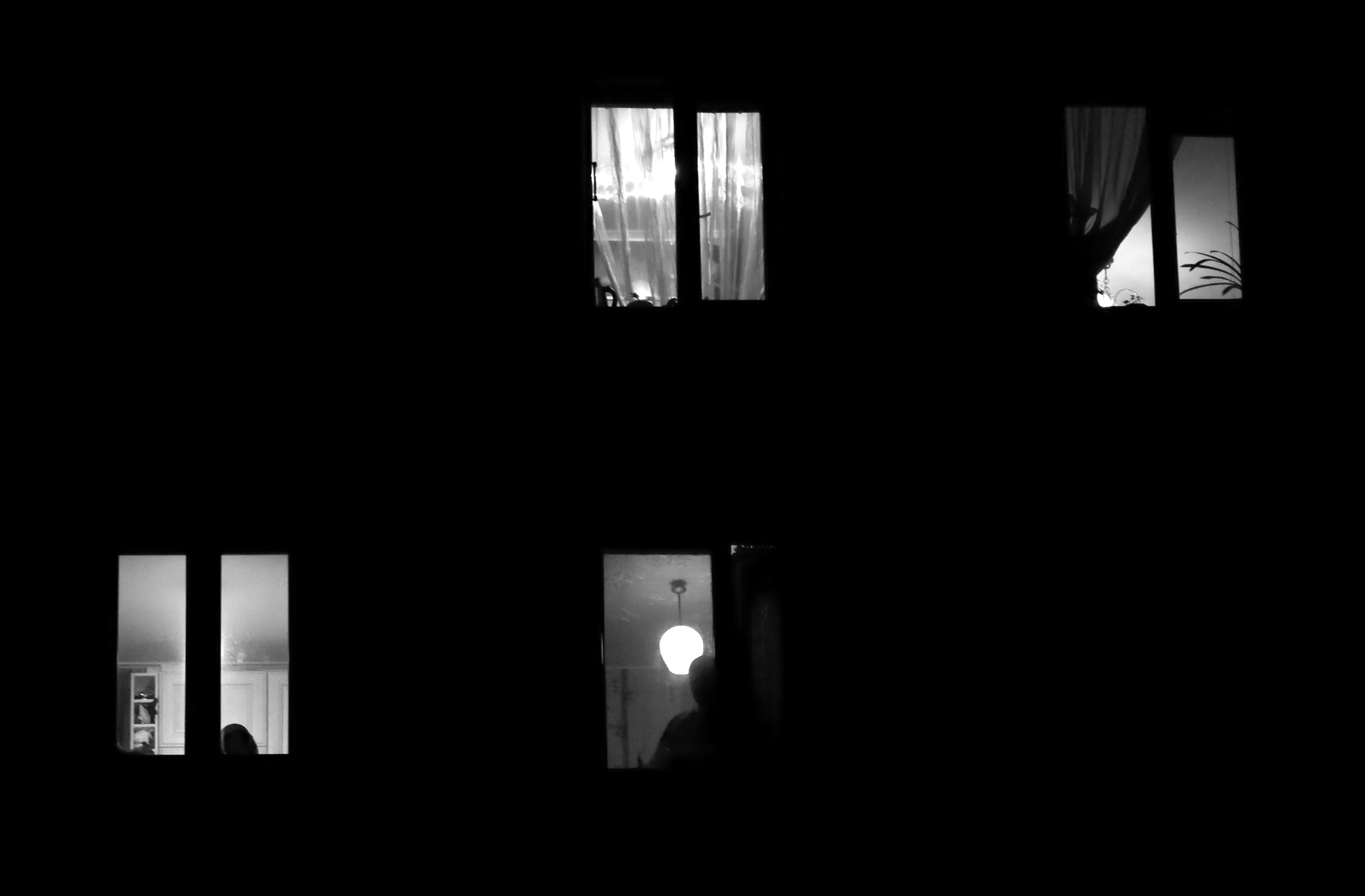

A few minutes later a dog started to bark, and suddenly Jude was staring down at us. She was not the only one. A light went on in Anne’s bedroom, and I saw her in the window.

Mark told me to leave. I’ll deal with her, he said.

I’m not going, I said. She’ll be happy for us. I mean, she said we could. She wanted us to.

This was a rather optimistic interpretation of Anne’s frustrated just-go-ahead-and-do-it speech. In fact, she was furious when we went inside. Most of her rage was concentrated on the complete outrageousness of our having done it in her driveway, of all the places in the world, and then parading in to tell her about it. This was not what I had in mind, she said quietly, sucking on her cigarette. Then she started screaming.

Anne, calm the fuck down, said Mark.

I guess I should go home, I said.

Yes, you should, said Anne. Zip your jeans on the way out.

Anne exiled me from her life for a while and passed me in the halls at work without a glance. I stayed away from Mark and spent more time at my bungalow.

As the days went by, I couldn’t take the distance between Anne and me anymore. I had been making overtures of friendship at work for weeks, but she wasn’t buying it — no lunch at Arby’s, no laughing at my jokes, no nothing. I decided I would just show up at her house with a bunch of presents for Rose. When Anne found me on her doorstep holding gifts, she laughed with resignation and invited me in. We sat and ate a bowl of popcorn with butter and nutritional yeast.

After Rose went down for her nap, Anne began to tell me how difficult things had become with Mark. He was really beginning to scare her. He had been morose for weeks, distant and mean. He slept till the afternoon every day and got drunk or high at night.

I asked her if she had been seeing the musician.

A little, she said. She told me he was furious about Mark’s behavior and worried for her and Rose. He was also talking about leaving his wife so they could be together.

A few days later, on my twenty-third birthday, Anne gave me a copy of the I Ching. When I opened the cover and saw the inscription, I cried: “To Marion, delightful friend, beloved sister.”

In preparation for my move to New York, I held a yard sale. It was a gray day, and my possessions looked even dingier than usual. People drove up, slowed down, then sped away, eyes averted.

By the time Mark rode up on his bike in the early afternoon, I was sitting on the front steps under threatening clouds with the majority of my earthly goods still surrounding me. In my lap was a diet soda and a cash box and, on my head, a battered Stetson I would sell if anyone asked.

I thought I might not see you, I said.

I couldn’t let you go without saying goodbye. He spoke dully, as if half asleep.

He dragged his bike onto the curb, leaned it against my futon platform (some slats broken, only fifteen bucks), and sat down beside me. My bare leg touched his worn Army pants. For a while we just sat there in silence, looking through old literary journals I was trying to sell.

I’m not going to sell anything, I sighed. And it’s gonna pour any minute. What am I going to do with all this shit?

Mark got up and began to look around the yard. OK, what do you got? Books? I need books. Bras? Bandannas? Spatulas? I need spatulas. Record albums! Socks!

Then he picked up a brown porkpie hat, pulled it low over his eyebrows, and leaned on the cane I’d used briefly when I had water on the knee. Hunched over, he hobbled toward me and slowly sat on a coffee table. There were so many things in my youth that I could not understand, he said in a quavering voice. Now I am an old man, and I look back on my life with many regrets. So many regrets, he repeated, shaking his head sadly. He looked at me, then rose slowly, unsteadily, on his cane and made his way toward the road. I realized he was about to climb on his bike and leave.

Wait! I called. Don’t go yet.

He paused, then tossed me the hat.

Why don’t you just come with me? I asked.

Would you really take me?

Would you really come?

We looked at each other. Well, that settles it, I guess, he said. He got on his bike. You be careful in that big city.

Come see me! You should! We can do a show up there!

I ran to him and hugged him, and he stood there, letting me. Just as I was about to drop my arms, he hugged me back and kissed me on the mouth. Then he pushed me away.

Remember me, he said, and he jumped on his bike and started pedaling down the street.

The night before I was supposed to leave Austin, all I wanted to do was stop the clock and sit in the living room with my housemates, but I had to pack.

It was evening when my room was finally empty and the truck was full. I called to have some pizza delivered. It didn’t come and didn’t come, and that is why, when the phone rang, I was sure it would be the delivery boy asking for directions.

But it was Anne.

He hung himself, she said. Her voice cracked. The police just got here.

What happened?

Oh, God, she sobbed. I came home this afternoon because I was worried about him. He was fooling around up in the attic, so Rose and I went to take a nap. At some point he woke me and asked me if I wanted to make love, and I said no and fell back asleep.

I could hear a police radio in the background, footsteps, other voices. When we found him, she said, he was so cold, Marion. So hard and so cold.

I told her I would come over immediately. The rest of that night was a blur: As I left the house, I noticed the pizza delivery boy across the street. He was going to the wrong house, but I didn’t do anything about it. I remember seeing the thick white rope that had been around Mark’s neck. Somebody said Rose should have something on besides a diaper. Anne’s friend Susie went around lighting candles, and Rose followed her, blowing them out. Anne talked to me as if I were Mark: Oh, baby, it wasn’t that bad, it wasn’t that bad. The dog barked at the police, barked at the paramedics, barked till we had to lock her in the shed.

I stayed another few weeks in Austin before I left for good. I felt like I didn’t have the right to mourn Mark. Everyone thought of me as Anne’s friend; not many knew about my fling with Mark. Even if people did know, I doubt they planned to send me sympathy cards: Sorry for the Loss of Your Best Friend’s Man Who You Fucked in Her Driveway.

I saw Mark in his casket with pancake makeup covering his skin and bruises on his neck. It would have been more natural to see him in his familiar whiteface than in that funeral-home flesh paint.

I drove around the United States and Canada for a few months, then landed in New York City. It took a long time for me to realize that drinking too much and having one-night stands was not a particularly useful way of dealing with my grief. By the next year I had written about two dozen drafts of a poem called “Waiting for the Pizza.” I still didn’t understand why Mark had killed himself.

When Anne visited me twenty years after Mark’s death, we spent an afternoon in Baltimore, pushing my daughter’s stroller around the Inner Harbor, talking about who we had been and who we had become. I was chagrined to realize how many of my recollections had been distorted and self-serving. I had things mixed up in such a way that all of my bad ideas and actions were less bad and less mine. I had told myself, and had come to believe, that I was just a bystander swept up in the action.

Well, Anne said, it’s true you were swept up.

But she was giving me too much credit. I’d seen a tornado coming and run toward it, my arms spread wide.

A different version of this essay previously appeared in the author’s collection Above Us Only Sky (Seal Press).

— Ed.