When Thom Goertel began taking pictures at Old School Boxing in Fort Washington, Maryland, the atmosphere was formidable: the music was loud, the air thick, the lighting poor. “It was perfect,” he says. The third time he showed up, he brought his writer friend Jim Kuhnhenn, who talked with the owner, Buddy Harrison, about the history of the no-frills boxing gym and the diverse clientele it attracts. Some people come there just looking to get in shape, but others are searching for a way out of the poverty that’s all too common just across the Beltway in Southeast Washington, D.C. Though a violent sport, boxing can also provide an escape from the violence of the streets. At its best, it’s about realized potential, mental focus, well-timed footwork, and respect for your opponent. These are the qualities that Old School Boxing tries to teach, sometimes for free, to anyone who walks through its doors. (Facebook @oldschoolboxing)

— Ed.

By the time Buddy Harrison was fourteen, in 1976, he’d already been in and out of reform schools. He would hang out with older guys, ex-cons mostly, pitching quarters outside a pizza joint in Southeast Washington, D.C. In between tosses he’d hear them boast about their time in prison. He says, “I literally felt like a lesser person because I’d never been there.” By the age of nineteen, his turn would come — a long sentence for armed robbery. “I told myself, ‘I made it,’ ” Harrison says.

Paroled after almost ten years, he returned to the streets and began selling crack cocaine, making him one of the few white dealers on the southeast side of the city. His story could have ended there, but Harrison had a singular passion. He liked to box. Harrison had been fighting since he was a kid, and inside prison the ring had been a common ground. When his son, Dusty, was born in 1994, Harrison ended his criminal career and dedicated himself to making the boy a champion. He built a gym — just a heavy bag and a makeshift ring — in the basement of the Naylor Gardens Apartments, where he lived, and invited kids from a nearby elementary school to be Dusty’s sparring partners (after getting permission from their mothers).

For all of Harrison’s devotion to Dusty, though, his life still looked bleak. “One night,” he says, “I drop to my knees. I’m by myself in the apartment. I have no idea the exact reasons. And I begged, and I cried like a baby, and I said, ‘Jesus, come into my life.’ ” After that, for Harrison, the gym became not just about Dusty but also about the other kids. They were from tough neighborhoods, and boxing kept them off the streets. They learned discipline, self-confidence, even humility. Harrison bought them pizza and took them to boxing tournaments. “Sometimes they’d win; sometimes they wouldn’t,” he says. “But they won anyway.”

By the time Dusty turned eight, Harrison concluded that he needed a better place to train. In time he settled on a cramped cinder-block building inside the Rosecroft Raceway complex, just beyond the Beltway in the city’s southern suburbs. The gym he started there lives up to its name — Old School Boxing. In a time of sparkling, spacious fitness centers with cable machines and group cycling rooms, Old School is spartan in its simplicity: free weights, ten heavy bags, two speed bags, a dip bar, and four treadmills. A ring takes up most of the inside. The smells of liniment and sweat mix with the leathery scent of bags and gloves.

The gym’s regulars are black, white, and Latino. A few are professional fighters, like Harrison’s son, who went on to become a welterweight champion. The rest fight on the amateur circuit or simply train for fitness. Inner-city and suburban teens travel up to two hours to get there, alone or with parents. Muscled young men share the ring with hard-hitting women. A seventy-five-year-old former government lawyer stops by once a week to keep trim. A PhD candidate volunteers as a coach. In 2014, during the tense aftermath of the police shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, Harrison decided the young fighters at the gym needed to get to know police officers, and vice versa. So he began offering free memberships to police in D.C. and Prince George’s County. Now officers often train with ex-cons and troubled youths at Old School.

For Harrison this is not a money-making operation. Many of the inner-city teens pay a reduced membership fee or no fee at all. And though the Rosecroft Raceway doesn’t charge to rent the space, the costs of maintaining the gym — gloves, ring, equipment — fall to Harrison. He’s had patrons along the way, but when he needed to install a bathroom and shower, he sold his car to finance it.

An unmistakable figure with his flattop haircut and sleeveless muscle shirt, Harrison doesn’t hide his past. A giant banner on the wall features his Prince George’s County mug shot alongside a recent picture of him bowing his head in prayer and a quote from motivational speaker Zig Ziglar: “Every choice you make has an end result.” Harrison’s generosity is known beyond the gym. On weekends he can often be seen distributing clothes to homeless men and women in downtown D.C. “It never fails,” he says. “If you be kind and treat people right, it will come back to you.”

Sebastian Sanchez (right) spars with trainer Japreme Eloheem.

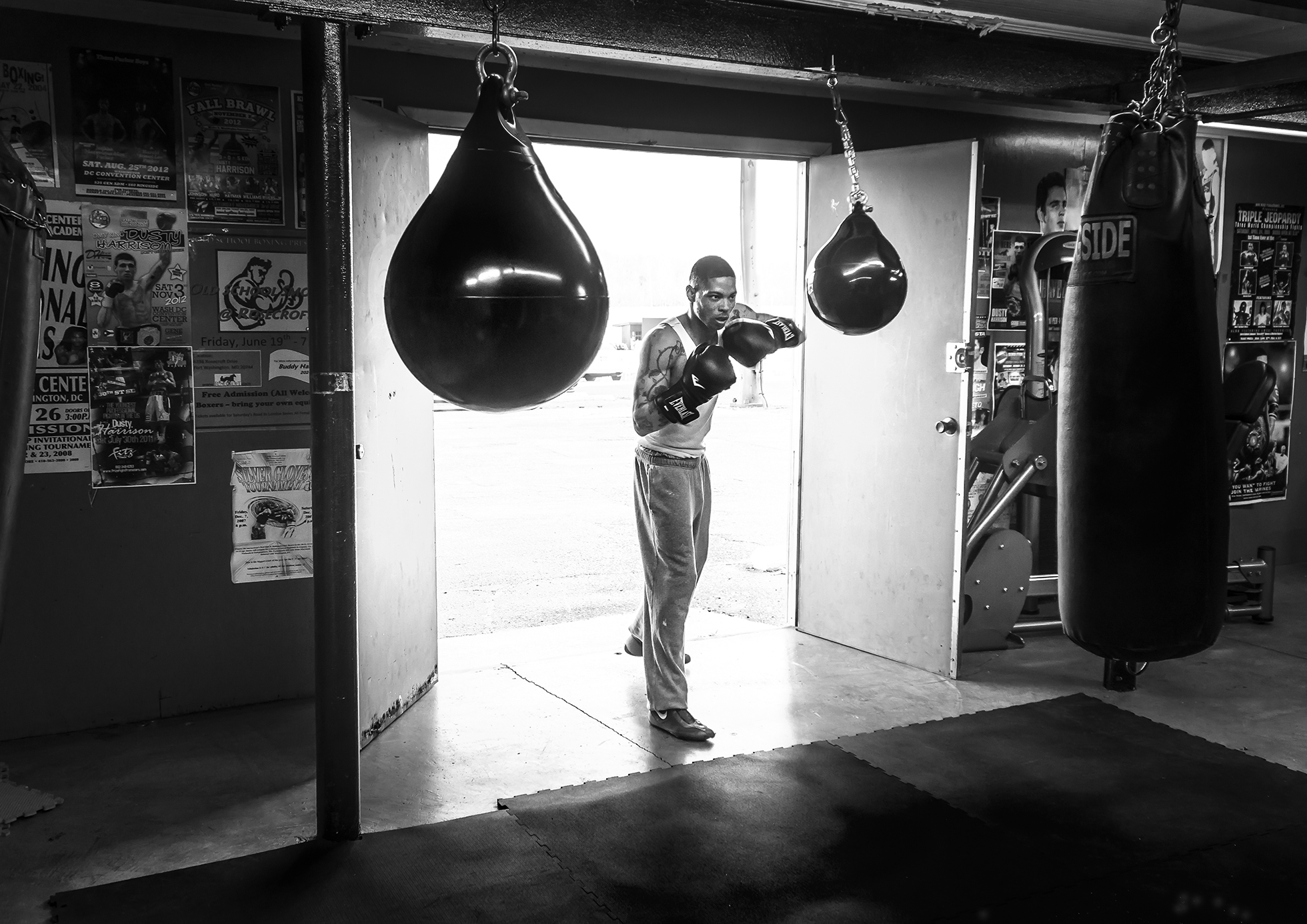

After a recent pro debut, Nathaniel Davis works a bag.

Waiting to spar, Miss Soldier watches other boxers in the ring.

Jordan King intensely studies a bout.

Asaan Jenkins’s trainer secures his headgear for sparring.

Darnell Pittman shadowboxes in front of a mirror.

Crisanto “Santos” Lucio waits his turn to spar in front of a wall-sized mug shot of the gym’s owner, Buddy Harrison.

Antonio Brothers recovers after sparring.