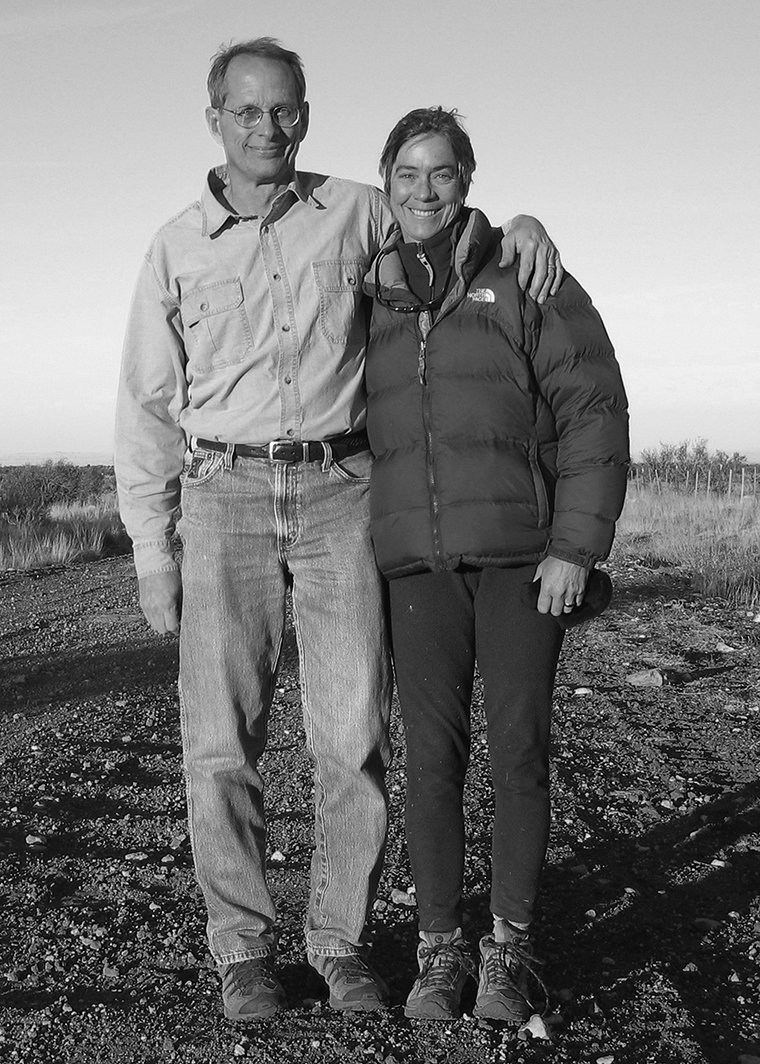

I met David Mattson in 2015 on a trail where we were both walking our dogs. We weren’t far from where he and his wife, Louisa Willcox, live in southwest Montana, about an hour north of Yellowstone National Park. He and I didn’t speak the first time we crossed paths, but the next time, our dogs recognized one another and stopped to say hello. Mattson and I let down our Montana reticence and chatted. He doesn’t like to talk about himself, so it wasn’t until later, when a friend told me in reverent tones about Willcox’s advocacy for grizzly bears, that I learned what an important role the couple have played in protecting bears in and around Yellowstone and Glacier National Parks.

Willcox and Mattson are cofounders of Grizzly Times (grizzlytimes.org), a blog and podcast that since 2015 has publicized the plight of grizzly bears and promoted compassion and respect for them. They also seek to preserve the ecosystems the bears depend on for survival and to restore a “sense of the sacred to the wild.” Willcox has been a bear advocate for more than thirty years and has worked for the Natural Resources Defense Council, the Sierra Club, the Center for Biological Diversity, and the Greater Yellowstone Coalition. She has a master’s degree in forest policy from the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies and received a lifetime-achievement award from Yale in 2014. She specializes in public outreach to promote better understanding of bears.

Mattson studied grizzlies through intensive, on-the-ground fieldwork in Yellowstone from 1979 to 1993. He later spent ten years in the Southwest focusing on mountain lions before returning to Montana. He has been a research wildlife biologist for the U.S. Geological Survey and has held positions at Yale and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Together the couple are leading the fight against “delisting” — the removal of grizzly bears from the list of species covered by the federal Endangered Species Act — arguing that the isolated bear populations around the national parks are still imperiled and nowhere near large enough for long-term stability. “To us,” they write on their website, “grizzly-bear recovery is not a technocratic problem; it is a spiritual and moral one.” Before I met them, my knowledge of grizzly bears was limited to what I’d seen watching Grizzly Adams on television in the 1970s and some family vacations to national parks, where I once saw a bear get on top of a vehicle and rock it during a traffic jam. After our conversation I had a new appreciation for the connections among humans, bears, and other wild species.

DAVID MATTSON AND LOUISA WILLCOX

Savannah Barnes: Louisa, you’ve called grizzlies a “portal.” What does that mean?

Louisa Willcox: If you look long and hard at grizzly bears and really study their behavior and habitat, you eventually find your way to the entire ecosystem, from ants to bison and everything in between. Basically, grizzlies are a window into the health of an ecosystem like the northern Rockies. And, as we’ve learned from their population collapse, they are also a window into human cruelty and intolerance.

Bears can show us a potentially different relationship with nature, which is maybe akin to an older, forgotten relationship we once had with bears: a kinship, a reverence for them, before we killed them off systematically to make way for our vision of utopia and tamed farmland.

With each big proposal to reduce bear numbers, we are faced with the question of who we want to be as human beings. Do we have a heart big enough to accommodate bears? Not many politicians do. There are some bear allies, like Congressman Raúl Grijalva from Arizona, who is now chair of the House Committee on Natural Resources. But there isn’t anyone like him in our region, which is unfortunate. When I started in conservation, there were friends of grizzlies in Congress: Lee Metcalf, Mike Mansfield, and Pat Williams in Montana. We had a long, proud tradition of people who championed endangered species and wilderness.

Savannah Barnes: How many bears were there in the greater Yellowstone region when you first arrived in the seventies?

Louisa Willcox: Maybe 350.

David Mattson: To put that in context, in Montana there were probably between nine and ten thousand grizzlies before the Europeans came, and in Wyoming between four and eight thousand. Humans eliminated 98 percent of the bears within these two states.

This gets back to what Louisa was describing: that impulse to dominate, which manifests in intolerance, killing, and hard boundaries. The early settlers went forth to “cleanse” the West and make it “safe” for women and children. That gave settlers the excuse to kill anything large and ferocious.

How we deal with grizzly bears and mountain lions is not that far removed from how we deal with refugees at our southern border. It really is a test of our compassion.

Louisa Willcox: Humanity underwent a real cultural shift beginning with the rise of agriculture ten thousand years ago. Suddenly there were fields to protect and walls to build. There were “good” animals like goats and pigs, and “bad” animals like wolves and bears, which had to be dispatched.

But we know from older stories, dating back fifteen thousand years or more, how important bears once were to people in the Northern Hemisphere. There’s the Native American legend of the woman who married a bear, and other stories about kinship and getting guidance from bears. People would find the North Star by looking for the constellations Ursa Major and Ursa Minor, or “Big Bear” and “Little Bear” [better known in North America as the Big Dipper and Little Dipper — Ed.]. Bears have always been a powerful influence on us. And yet we have forgotten this. In some cultures, like Native American cultures, it hasn’t been forgotten. They still view bears as “relatives.”

We can choose which story line to preserve. Do we want a deeper, richer relationship with nature, or do we want to just kill everything and live through our smartphones?

Savannah Barnes: Does it really make sense to view wildlife as either villains or allies? The reality seems much more complicated.

Louisa Willcox: Stories we tell about wild animals are often exaggerated or stereotypical, and biased according to our mood or understanding. We may see wild animals as “good” or “bad,” when they are actually living beings trying to navigate a complicated world. Rather than being curious about what an animal is doing and why, we pass judgment.

David Mattson: We tend to think of grizzly bears as ferocious and savage, but bears also represent a powerful female energy: how Mother Nature can be indifferent to us. Not only indifferent; she can kill us, destroy the things we prize and build.

Mother Nature is this potentially destructive force that we want to erase, but mothers are also protective and nurturing. People are more receptive to the idea of a mother grizzly bear mauling somebody to protect her cubs than they are to the idea of some bored grizzly tearing somebody’s head off. Our relationships with both nature and bears are complex.

Louisa Willcox: Back when I was with the Sierra Club, we did focus groups on grizzly bears in cities in Wyoming and Montana, places that are not liberal hubs. A woman who was quite terrified of bears asked, “Isn’t it true that most attacks are mothers protecting their young?” When we said yes, she said, “A mom’s gotta do what a mom’s gotta do.” On the one hand she was really scared, but on the other hand she totally got it.

People identify with bears. I’ve heard ranchers say, “They’re just making a living; they’re a lot like us. They’re resourceful. They’re tough.” A beleaguered Westerner identifying with a grizzly bear is kind of odd, but it actually works in the bears’ favor: at least they are not being demonized, as they are in Outdoor Life magazine and by the NRA.

David Mattson: There’s so much about bears for us to connect with: They are intelligent omnivores. They provide extended maternal care for their offspring. They can stand on their hind legs. They can manipulate things with their paws. I learned about edible native plants from following bears around. I think that, for millennia, hunter-gatherers were probably watching and learning from bears.

Bears can show us a potentially different relationship with nature, which is maybe akin to an older, forgotten relationship we once had with bears: a kinship, a reverence for them, before we killed them off.

Savannah Barnes: What are some examples of tribal peoples’ relationships with bears?

Louisa Willcox: It depends on who you talk to. There are tribal business councils actively trying to develop oil and gas resources, which threatens bear habitat. But then you’ve got the traditionalists, the keepers of the old stories, who are often at odds with the business councils.

David Mattson: In North America there was quite a bit of difference between tribes geographically. In the boreal forests, there was a tradition of native people hunting bears for meat. There wasn’t much meat in that environment, so you can understand why they would kill bears. In the middle latitudes and the interior of the continent, there were lots of bison and elk, and native people didn’t kill bears for meat. They did occasionally kill a bear and use the body parts for spiritual or ceremonial purposes, and as a mark of potency, but all of this was colored by deep respect. They credited the bear with a spirit.

In places like California native people primarily feared and avoided bears because there were so many of them.

Savannah Barnes: Where are the most grizzlies in the U.S. now?

Louisa Willcox: Grizzlies remain in five ecosystems, but the two strongholds are around Yellowstone and Glacier National Parks. There are maybe 1,800 total in the contiguous U.S. and Canada, down from a peak population of between 50,000 and 75,000.

Grizzlies are currently pushing out from Yellowstone and Glacier. There was a bear killed last fall in eastern Washington, and one killed on a ranch near Two Dot, Montana. Another grizzly made its way onto a golf course in the Bitterroot Valley, where it was eating earthworms and inconveniencing golfers. The bears are going where the habitat is still suitable and where humans will tolerate them. There is enough suitable habitat to possibly double the current numbers in the Lower 48 and Canada, which is probably what’s going to have to happen in the long term to get to any kind of viable population recovery. The question is: What are people going to do in response to that? There are more and more people here, especially around the greater Yellowstone and Glacier ecosystems. Are they willing to tolerate grizzlies?

David Mattson: The question is also: Who has the greatest political sway? Unfortunately I think the people who are well connected politically are also those with regressive worldviews that hearken back to the devastation of the nineteenth century.

Savannah Barnes: What are the main threats grizzlies face now?

Louisa Willcox: Habitat loss is a fundamental challenge. Also humans with guns. The leading causes of grizzly-bear mortality in Yellowstone are big-game hunters and livestock-related conflicts. In the case of hunters, they aren’t necessarily hunting bears; they are hunting elk and other game, but they kill bears — supposedly in self-defense. There is very little sign these hunters even have bear spray on them. What they do have is huge amounts of firepower and fear.

David Mattson: The agriculture-related conflicts often involve the depredation of livestock, which is increasing. There are livestock operators all up and down the Rocky Mountain Front who are not having much of a problem with bears, but then you have these places where there’s problem after problem. Most glaring is the Upper Green near Pinedale, Wyoming, where these millionaire ranchers have a real attitude about bears. Every year ten or fifteen bears are killed down there, which is outrageous. They can afford to do better.

There is a misconception that bears will inevitably be killed because of such conflicts, but we know that you can have bears in agricultural landscapes as long as people are willing to take minimal measures to deploy what I call a “coexistence infrastructure.” This includes putting up electric fencing around calving areas, lambing areas, and beehives, and not putting dead cattle in a bone pile behind the ranch house.

Savannah Barnes: How much of a problem is automobile traffic?

Louisa Willcox: It’s a small portion of the total killed each year. Out of sixty-five dead bears in the Yellowstone area, maybe eight deaths were road related.

David Mattson: In the northern Continental Divide it was eighteen. But in Yellowstone National Park you have hundreds of tourists lined up along the roads, watching bears a couple of hundred yards away. That is a lot of proximity between large numbers of people and bears, and the bears do just fine.

How often people encounter bears is just half the picture. The other half is: What happens when humans run into bears? We tend to think about the danger to humans, but we are far more lethal than they are. The interaction is far more likely to produce a dead bear. There is nobody more lethal than a trophy hunter with a gun and a license to kill a bear.

The least lethal is a family from New York City who have come to Yellowstone thrilled at the prospect of seeing a bear. So, yes, it matters that we have lots of cars traveling at high speeds on interstates, but a large number of people, in and of itself, is not necessarily a problem.

Look at the contrast between the United States and Europe. We eliminated bears from 98 percent of their habitat in the contiguous U.S. within about a sixty-year period. Today we have bears only in the areas with the lowest densities of human population.

Europe still has 40 percent of the bear distribution that it had six thousand years ago. In Romania, in the Carpathian Mountains, there are probably eight thousand grizzly bears. That would be like putting eight thousand grizzly bears in the Poconos and Appalachian Mountains just west of Washington, D.C. So it’s not just numbers of people that cause problems. Coexisting with grizzly bears is far more about what’s going on between people’s ears — their attitudes, their worldviews.

Louisa Willcox: Not all roads are created equal. In several dozen places, for example, the highway administration has put in overpasses for wildlife. But then you have parks like Grand Teton, where they merely improved the roads and kept the speed limit high. That kills a bear or two a year. It doesn’t make any sense. It’s a park, after all. People should be driving slowly. It would be safer not just for bears but for moose and everything else.

Savannah Barnes: Is wildlife tourism a boon that helps preserve wildlife, or should we ultimately be avoiding direct contact?

David Mattson: Tourism is certainly a double-edged sword. Creating opportunities to see wild animals up close can expand support for protecting wildlife and provide economic incentives for conservation. On the other hand, it can easily be overdone. The trick is moderation — something we humans have shown we are not good at.

Savannah Barnes: What’s the natural life span of a bear?

David Mattson: More than thirty years. Due to the toll that humans take, the average is currently about ten years. Female bears don’t reach sexual maturity until about the age of five. Their litters are small — often only two — and they have them every three years or so. So most bear populations are on a knife’s edge. It comes down to whether females are able to produce a reproductive-age daughter.

Savannah Barnes: So, in order to see improved numbers of bears, it’s a thirty-to-fifty-year plan. The political situation is going to change numerous times during that period.

Louisa Willcox: We are not going to see recovery during our lifetimes, not anywhere close.

David Mattson: Not recovery as we would reckon it. There are considerable lags in the response of bear populations to the changes we make. Humans have demonstrated that we can kill off most of the bears in a landscape in pretty short order if we set ourselves to the task. It’s much, much harder to foster and sustain growth in populations.

Savannah Barnes: How do you talk to people outside of your region about the plight of the grizzlies?

Louisa Willcox: Actually they are a far easier audience! [Laughs.] Either they don’t think about bears, or they think bears are cool and have no clue what’s happening to them. Most visitors to Yellowstone don’t know that bears are getting killed at an unsustainable rate.

But there’s a hunger to know more, which explains the increasing numbers of visitors to Yellowstone and Glacier. People who live in places where there’s nothing but malls and asphalt sense that something is missing. They come here looking to get a taste of it, and so their kids can see it, too, before it’s gone.

We’ve screwed this planet over, and how we’ve hurt these magnificent animals — lions and bears and wolves — may be the most symbolic example of that. But there is a sense that we are losing something, and we’re trying for some reconnection.

David Mattson: We are our own worst enemies, in that we have long been destroying those things in the world that engender health. I think the “wild” is our word for all that was once so sustaining but is now largely lost. We need to experience a natural environment that is nurturing and health engendering.

Savannah Barnes: What are some ways that bears, specifically, can improve our health?

Louisa Willcox: There’s a lot of health research involving bears. For example, people who lie in hospital beds for a long time lose bone density, but bears don’t lose bone density during hibernation because they create the parathyroid hormone that maintains it. The parathyroid hormone has been replicated in a lab and is now being used in treating osteoporosis. Bears have amazing kidney adaptations and organs that don’t fail during hibernation. Their muscles get leaner but suffer no atrophy, so they can get around right away after hibernating. When I was going to meetings of the International Association for Bear Research and Management, there were always medical experts there presenting papers. How does a bear go into a den and seemingly die for months? How does a female bear give birth while she’s half asleep, then nurse for a few months with no nutrients coming into her body? There’s a point where science has no answers.

David Mattson: Bears are perpetually obese except for a brief period in the spring, but they don’t get type 2 diabetes. If we could just unlock those mysteries, we could have the same benefits.

Louisa Willcox: I think the mystery is important. We are never going to understand everything that goes on in nature. It’s humbling to realize that. It’s pretty horrifying to think that we could be destroying the last of these bears.

Savannah Barnes: What about bears’ ability to adapt to different food sources?

Louisa Willcox: They test everything that’s edible and can tell when the nutrition level is high enough for them to eat it. They just know. You’d better believe hunter-gatherers were watching this: “Oh, it’s the middle of July and the bears are on yampah? Yampah must be good right now.”

David Mattson: I’d been following bears around Yellowstone for seven years and had never once observed them eating sweet-cicely roots. At the end of one long day, I came into a patch of woods and saw all this tilled earth; bears had obviously been digging around. I dug up some roots of the sweet-cicely plant, took a taste, and thought, Wow, these are good. In subsequent years, when the bears stopped feeding on the root, I dug some up, and the fibrous taste was awful. There was something about that year, and the bears were on it, just like that.

Louisa Willcox: I get a little uneasy when I hear, “We need to save bears because they are the key to the next medical advancement.” That’s all about human interest: What good is it to us?

Years ago, when the Endangered Species Act was under attack — one of the many times it has been — the Endangered Species Coalition decided to argue that we need to protect bears because they keep the ecosystem healthy. And I thought, That’s not really the point. The point is that we have a moral obligation not to let bears wink out of existence. That’s why the Endangered Species Act was passed in the first place: because, as a society, we think extinction is wrong, and we have codified that belief in law. It’s not because other species are going to benefit us in any way.

David Mattson: Along those same lines, there are people who make the case for how we benefit economically by having grizzly bears: bears bring tourists to places like Yellowstone, and tourists spend a lot of money, which creates jobs. But I don’t think demonstrating an economic benefit is going to generate that much more support for grizzly bears. Support will come from people arriving at the heartfelt conclusion that we want grizzly bears to survive for intrinsic reasons.

Savannah Barnes: How did your childhoods prepare you for the work you do now?

Louisa Willcox: My family lived on a farm in what was then a very rural part of Pennsylvania. I spent a lot of time outside. After my dad’s death, when I was almost twelve, my seeking solace in nature took on a new importance. I would take long walks by myself. Once I found the greater wilderness at fourteen, I was never going back. The mountains and wildlife have meant everything to me. And I’ve been interested in grizzlies since I saw my first one when I was a teenager.

David Mattson: I grew up strongly affected by the harm being done to the natural world. Even as a little kid, riding in the back of a car through the Black Hills of South Dakota, I imagined that I had godlike powers and could erase all the wounds caused by the human urge to dominate and exploit: billboards, tourist traps, new housing developments. What I did with my adult life grew out of that — spending a lot of time by myself in the woods, being curious, and developing an appreciation for places untrammeled by humans. I would sit on the floor as a kid with maps and look for the empty spots, places that didn’t have roads or towns. I would see a mountain range where there was no manifestation of human presence and think, I want to go there.

It’s been a constant struggle in my life to come to terms with that chronic sense of loss without becoming alienated and angry.

Savannah Barnes: How do you deal with it?

David Mattson: By understanding that a lot of my anxiety and distress flows from the expectations that I place on the world. The violation of nature for me is like a death. I react to it with grief.

Is it wrong to desire a world that is a more compassionate, benevolent, accommodating place for all beings, whether they are humans, animals, or plants?

Savannah Barnes: What sort of personal interactions have you had with bears?

Louisa Willcox: Once, I was in the Absaroka Mountains with mountaineering students in the late seventies, and I wasn’t paying attention. I knew grizzly bears were around and kind of vaguely knew they were on the endangered-species list, but I didn’t really know anything about them. It was dusk, and I was trying to find a camp. I was charging down this hill when I almost ran into a bear in a meadow.

It looked at me, and then it just turned around and vanished. In that glimpse I saw the same surprised “Oh, shit” expression a human would have, and a certain wisdom, a certain intelligence. It made a massive impression on me. I became curious about the plight of grizzly bears.

When I got to graduate school at Yale, I ended up writing a paper about grizzly-bear recovery. A memo had been leaked from someone in the Department of the Interior who said there might have been, at that time, only forty-seven reproducing females left in the ecosystem. They were really afraid grizzlies were going extinct. So that became the topic of my paper. I wound up at the Teton Science School, taking classes and teaching. Then, when I got to the Greater Yellowstone Coalition, grizzly bears were a part of my beat.

Even though my job was to protect the whole ecosystem, grizzly bears were a convenient focus, because if you protect bears, you protect a lot. I dove in deep there. I wasn’t trying to provoke bears, but I had a few close calls. One time a bear was behaving passive-aggressively, getting closer and not looking at me and kind of zigzagging. I thought, OK, it’s time to leave. But I never had an experience I thought I wasn’t going to live through.

We think God put us at the center of the universe, but we put ourselves there and declared everything else lower than us, including animals like bears and dogs. We are not better than they are. We are just fellow travelers.

Savannah Barnes: Has anyone accused you of anthropomorphizing bears?

Louisa Willcox: Oh, yeah. I think that’s a silly argument. Who has a dog and doesn’t understand that they have the same range of emotions we do? And personalities! They are each quirky and neurotic in their own unique way.

We think God put us at the center of the universe, but we put ourselves there and declared everything else lower than us, including animals like bears and dogs. We are not better than they are. We are just fellow travelers.

David Mattson: There is nothing that can fill space like a bear. Bears in general, and grizzly bears absolutely, have a presence that is unmistakable. I can be going through the woods, and I can see a moose; I can see an elk; I can see a hawk — you name it. But in that moment when I see a bear, it is present in a way that no other animal can be.

I have been able to interact with bears in a way that better acquaints me with them as individuals. They do have personalities. For a couple of years we followed a handful of bears around to study them, trying to get a detailed picture of their lives. This was before the use of GPS satellite technologies, so you actually had to be on the ground with the bears. It was an inane study, because we’d also periodically attempt to elicit a response from the bears — basically bother them to get a reaction.

It was interesting to get that intimate view of these animals and the differences among them, but in our interactions with the bears we were always a little on edge, because we’d deliberately approached them. One female had three cubs almost as big as she was. We approached to see how they would respond. It was decision-making by committee: I could see the cubs looking at each other and then looking at the mom, like, What are you going to do? I don’t know. What are you going to do? And then they ran off. It was a window into how bears communicate and make decisions in those kinds of moments, their sentience and emotional lives.

For me, one benefit of having grizzly bears in the world is that, when I am around them, I am paying attention! They can tear my head off. So I’m listening for all of the sounds, like the buzz of flies that may be a sign of a carcass, which might have a bear feeding on it. I’m listening to the call of ravens, feeling which way the wind is blowing, smelling everything. Nothing grounds you in the moment more than having a bear around. It can be a terrifying experience, but for me it’s incredibly enriching.

Savannah Barnes: Humans have relationships of mutual appreciation and benefit with our pets. Do you think such a relationship can exist — beyond isolated incidents — with wild animals?

David Mattson: Yes, of course, if people are patient and kind. The ancient stories remind us of relationships with animals that have been lost or forgotten. Modern society has largely sealed itself off from intimate relations with nature, but that doesn’t mean that these connections can’t be forged again. We could be healthier, happier, and humbler if we could reimagine our connections with wild animals. Who wants to live in a world without wildlife?

Savannah Barnes: Is it possible to earn a bear’s trust?

Louisa Willcox: Absolutely. That’s something that doesn’t get talked about a lot, because it’s seen as a violation of the common belief that you have to keep your distance. Certain people, certain personalities are really good at it, just like with dogs. It is possible to get the trust of a bear such that it will literally follow you. I have not had that happen to me, but I did a podcast with Charlie Russell, a Canadian naturalist and rancher who had some amazing experiences. He ended up raising three orphan cubs on Kamchatka Peninsula in the far east of Russia and releasing them into the wild. Charlie died in May 2018. But he felt it was his obligation to say that we can allow bears in much closer to us than we ever thought possible. He argued with scientists who felt his message was dangerous, that he was inviting other people to become the next Timothy Treadwell. [Treadwell was a bear enthusiast killed by Alaskan grizzlies, and the subject of the documentary Grizzly Man. — Ed.] Charlie knew Timothy and thought he made a lot of mistakes, as did I and others who knew him pretty well. Charlie wasn’t stupid. He had an electric fence around his cabin in Kamchatka. He always had bear spray and used it on bears who pushed the limits. But he had relationships with bears that were quite amazing.

I was once in the Queen Charlotte Islands in British Columbia to observe spirit bears, a subspecies of the black bear, and there were several bears that knew the researchers there. They definitely had a personal connection. They were wild bears and were not fed by humans, but they had developed a fondness and a trust. We can’t forget that bears and dogs came from the same ancestors millions of years ago. They are not that different. Of course they can trust. It’s all about whether we decide to reciprocate and invest the time in an individual.

Savannah Barnes: Did what happened to Timothy Treadwell affect the study and management of grizzly bears?

Louisa Willcox: It certainly did right after his death, especially in Alaska’s Katmai National Park, which is where it happened. There was a lot of fear of Timothy wannabes up there. But I don’t hear his name thrown around the same way anymore.

Our Romanian friends have relationships with bears. It’s very common there. If you’re not shooting bears all the time, keeping them in a constant state of stress, and if there’s some stability in the ecosystem, it’s definitely possible to have relationships with bears. It’s all about the stability and predictability of people. That’s why Charlie had to leave North America and go to Kamchatka to see how close he could get. He was looking for a nonhunted grizzly-bear population, one that wouldn’t immediately flee.

Charlie was working with a neurologist on the psychology and neurology of bears. He started on the British coast with this female bear he called Mouse. He was leading tours there, and he kept seeing her, and she kept letting him come closer and closer. Finally she let him rub her belly with a stick! [Laughs.] If they have a connection with you and know you are going to be civil with them, you can actually get pretty close.

Not many people are willing to talk about this, because they think curiosity-seekers will get mauled, and that will be bad for bears.

Savannah Barnes: What have you learned from bears?

Louisa Willcox: I don’t know much, actually. Maybe that’s what I’ve learned: that I don’t know much.

Savannah Barnes: But what have bears inspired in you?

Louisa Willcox: I can’t boil it down. What I am honestly left with is a sense of awe and wonder that they’ve made it this far, that we even still have them, given the overwhelming hostility toward bears in the American West.

We need more people devoted to wildlife issues, but I don’t see young people going into wildlife preservation the way I did. I see them going into climate change and sustainable food and the like, and those are really important, but we need folks who are dedicated to understanding other species and working on coexistence.

Savannah Barnes: What do you see lacking in today’s environmental movement?

Louisa Willcox: As the environmental groups get bigger and better-heeled, they answer to big bureaucracies. There are the pressures to raise money, until it becomes about what you are selling and how you sell it. It is a challenge to stay true to a mission when you have to answer to the money masters and the political masters.

Not so long ago there were lots of little ragtag groups and very few big ones, and now it’s the reverse. Bigger groups are dominating the table, and with that you have this echo chamber of environmentalists talking to each other and not talking to possible supporters or even trying to reach them.

As institutions have grown, so have the demands of working for them. I worked for the big institutions, so I know. I should have left a lot sooner than I did. I was going crazy. I couldn’t deal with it after a while. I was pretty good at raising money, but it was destroying my sanity. It’s not my community. It’s not enlivening.

David Mattson: As I see it, it’s partly about the corrupting effects of money. Given how our society is structured, we need money, but at large scales it really distorts priorities. So now you have environmental organizations that, rather than focusing on the issues, focus on where they can get money, so they can hire more staff, develop a bigger public-relations machine, and create more career opportunities. It’s not about nature and wild creatures at the core anymore. We need people who are dedicated to understanding and working on coexistence. They don’t have to do it exactly the way we did, working one on one with ranchers and the like, but they have to devote the time.

Living with animals like grizzly bears, wolves, and bison demands that we accommodate these other beings who impose constraints on us, that we find a place of openness for them — just like we have to do with other people.

Savannah Barnes: Is there a promising younger generation of wildlife activists that you are aware of?

Louisa Willcox: Yes, but they are scattered all over and not activists per se, but good young biologists, filmmakers, outdoor educators, journalists, and others who are speaking up for wild animals. The movement is diffuse but deep.

Savannah Barnes: In all the years you’ve spent talking to people, have you ever changed someone’s view of grizzly bears?

Louisa Willcox: I don’t know if you can really change the mind of someone who is completely hostile, but I definitely feel that I’ve made an impact with people who were conflicted. Over the years I’ve earned the trust of people I didn’t think I would, including one of the Safari Club leaders in Idaho. He is a hard-core trophy hunter, but he understood why I was taking the position I was, and he respected me for it.

I have the knowledge, and I’m not going to be cowed. You do get respect just for showing up to hostile meetings and not being intimidated and saying your piece. Even at hearings in Cody, Wyoming, where I was quite scared at times, as I left I heard, “Hey, thanks for what you said.”

When I started, no one knew what to do, and I had no direction from anybody. So I got in my car and just drove around and talked to people. I spent years working with independent loggers in eastern Idaho, who were getting screwed over by big logging companies like Boise Cascade. They were worried more about the big logging companies than they were about activists like me. I didn’t feel there was a problem with small logging operations, as long as they closed their logging roads once they were done. We ended up filing a lawsuit on behalf of grizzly bears, but I also wanted to resolve the issue on terms that were good for these independent loggers.

There was a conservation ethic, a respect for the wild, among some ranchers and loggers. They knew what they were doing was bad, but they were trying to survive. I actually helped them cheat on some timber sales. [Laughs.] I promised them that I was going to stand between them and other environmental groups that were trying to kill these sales.

As a Buddhist, I try to find this place of compassion for people like the independent loggers. One guy, who became my friend, had thirteen kids and was working illegally in this operation. I wasn’t going to turn him in. I liked him. [Laughs.] He didn’t have a problem with bears or what bears needed. That was a really hostile situation going in, and yet I met these cool people. That was a surprise. That’s what the Buddhist practice really is about: understanding there is goodness in everyone. It’s definitely a practice.

David Mattson: Living with animals like grizzly bears, wolves, and bison demands that we accommodate these other beings who impose constraints on us, that we find a place of openness for them — just like we have to do with other people.

We cannot have all that we want. There are others who also have demands on the world, and that requires us to find some middle ground, to negotiate some way of coexisting with these fellow sentient beings. We can benefit from that, in the sense that we can live lives of greater contentment by being less self-delusional. There is always that divisive idea that we can impose our will on the world. I think animals like bears help us find a more emotionally tenable way of living.

Over the course of American history we have gradually extended rights to more and more other beings. First it was just white males who were fully human; then women; then children; then people of other races and religions; then people with different sexual orientations. It’s about expanding the moral universe to ultimately include sentient beings who are voiceless, who literally cannot speak our language. We benefit from this because the world becomes a more benevolent, gratifying place for us to live in, too.