Early in my career as a photographer and aspiring writer, I asked myself: Why am I drawn to throwbacks, to the salt of the earth, to the poor and downtrodden? Why do I enjoy the company of such people? Why, among my subjects, are there no bankers, no businessmen, no city dwellers, no suburbanites, and no one fashionable or affluent?

Instead I was drawn to quite the opposite: curiosities, anachronisms, misfits, innocents, and angels. They quickly became my family. They gave me something my blood relatives could not, something fresh and immediate, accepting and nonjudgmental. And they connected me in a way neither spiritual insights nor my own class and culture could.

The words and pictures on these pages are all from Ethan Hubbard’s self-published book Salt of the Earth. Copies are available from the author at P.O. Box 292, Chelsea, Vermont 05038, or call 802-685-2025.

— Ed.

Mustafa, Farafra Oasis, Egypt (above)

In an Egyptian oasis I sat with a young schoolteacher named Mustafa and his workmen to eat breakfast: oranges, bread, salty feta cheese, beans, and two kinds of tea that he brewed on the ground. He was a magician with the twigs that he laid between three small white stones.

Everyone in the oasis said that Mustafa made the best tea, much better than the women. He would blow like a bellows to get the right heat for the water, and the tea would steep for a long time. Eventually he would add the rest of the water, sugar, and “nah-nah” (mint leaves).

I was always offered the first small glass. I would attempt to decline, but I was never successful in giving the tea to someone else, even though I sensed that they all longed for that privilege. Extremely gracious people, the desert Arabs.

Anne Burke, Berlin, Vermont

My good friend Anne exuded confidence that the world was beneficent. Abundance surrounded her. And in the 1970s, when skeptics said the small family farm was destined to fail, she proved them wrong.

“Life will always be challenging you,” Anne told me. “The trick is to polish all the moments to make them shine. That’s both sides of the coin, not just the pretty and easy ones. Each moment, each day is precious and should never be wasted or cast aside.”

I made this portrait in her barn. A shaft of light crept through a crack in the wall and spread across her face.

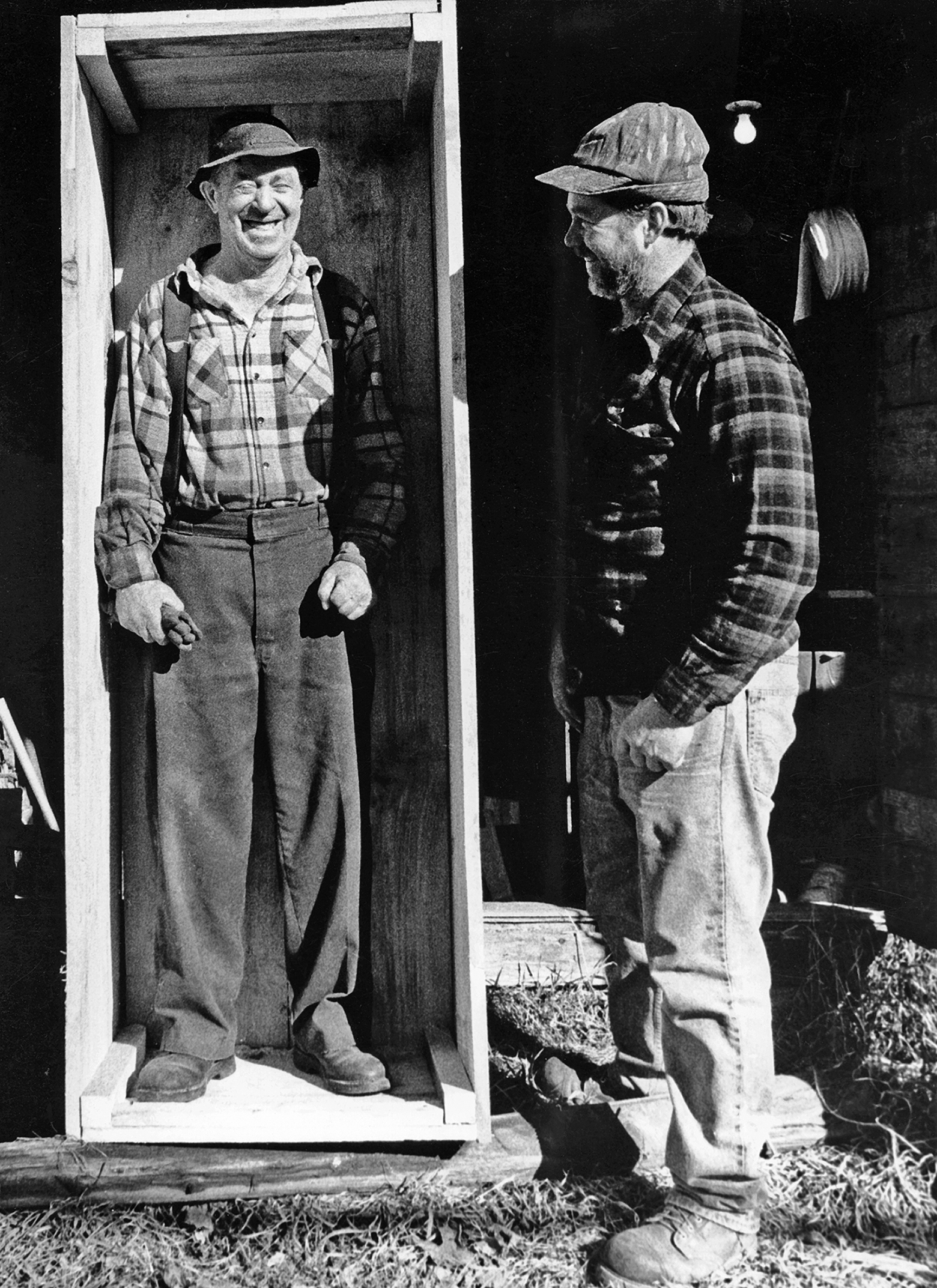

Francis Foster, Walden, Vermont

Francis was a man of the soil, a man with manure on his boots, dirt under his fingernails, and sawdust in his pockets. Sometime before Francis passed away in 2011, he jumped up from the breakfast table with an idea: “Well, by God, if I’m going into the ground soon, then I’ll make me a custom-made coffin to feel more t’home.”

He went and felled a white pine on his farm and milled it into lumber. Next he went to his forge and crafted the iron hinges for the lid.

He then tried out the completed coffin with his son Terry looking on. “If this ain’t the perfect fit for me — pine, wrought iron, and no fanfare — then, Christ Almighty, I don’t know what is.”

When Francis died, he was placed in his open coffin. His sixteen children and many grandchildren took turns stashing small mementos beside his body: an ax, some sweets, and many one-dollar bills.

Two draft horses pulled Francis’s body in a wooden wagon past the old spring, into the sugar woods, and finally to the grave site of his wife, Ginny. With the help of some worn old reins that Francis had used, seven sons, a grandson, and a neighbor lowered the coffin into the ground.

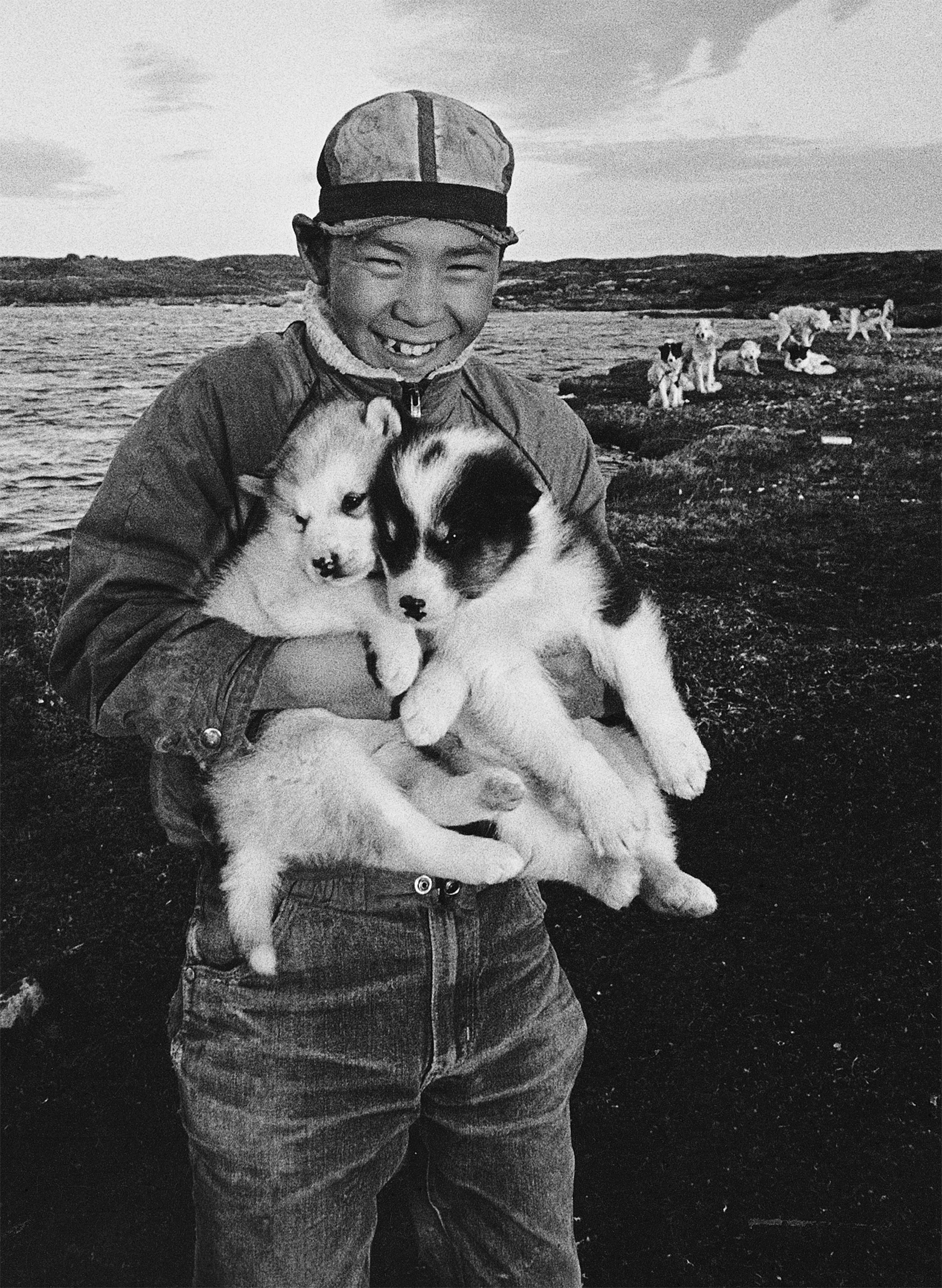

Ricky, Whale Cove, Canada

Riding in a small plane from Churchill, Manitoba, to Whale Cove, Nunavut, I soared over a strange and wonderful landscape. I had never seen any like it. Until a mere seventy years earlier, the Inuit had lived in this intensely cold climate as nomads for thousands of years. In the 1950s and ’60s the Canadian government relocated them into settlements. I spied a settlement on the horizon, and a huge Inuit man seated across the plane’s aisle reached out and tugged at my pant leg. “Whale Cove,” he said, and then did a pantomime of shivering with his arms crossed, as if to say, Ol’ whitey gonna freeze his ass off. A planeful of Inuits laughed. I came to know the people of Whale Cove as extremely warm and hospitable. Living in one of the harshest landscapes on the planet, they had to help each other to survive.

Susan Henry, Antigua, the Caribbean

Susan had lived a life of horrors as a worker in the notorious sugarcane fields of Antigua.

“It was the only work I could get when I was a young girl,” she said. “White bosses would rape me regular, stifling heat beat me down, and giant centipedes nearly killed me. English men attacked us regular-like, gave us the licks with the stick, and gave us only one shilling for a twelve-hour day. We was existing like slaves, like our great-grandparents who had their skin peeled off their backs with the master’s whip.”

In 1970, on vacation in Antigua, I came to know Susan and her seventeen grandchildren. In her old age she was determined never to let atrocities befall her charges. She worked from dawn to dusk to make sure that all were washed, fed, and presented with cleaned and ironed clothes each day for school.

I photographed Susan on her daily two-mile barefoot walk through the bush to Bloody Pond to purchase fish for her children’s and grandchildren’s supper.

Two brothers, Kosovo

For ten days in 2009 I lived in Kosovo and interviewed and photographed the inhabitants of a village. These two brothers were like wounded, wary fawns who had defied the odds and made it through hunting season. For six horrific years they’d experienced the daily nightmare of shelling and murder at the hands of the Serbian Army.

Through an interpreter the brothers spoke slowly and hesitantly: “We now have life. We have a new home. We have our village back, and we have our extended family. And we still have our Muslim faith. Praise be to Allah.”

Binda and her grandmother, Senegal

Through an interpreter I listened to a conversation between a Wolof grandmother and her granddaughter.

“Grandmother, how will love come to me? What is love between a man and a woman? Will I be successful?”

“Binda, love between a man and a woman is mysterious. Both of you will receive a beautifully carved box at the right age, and the directions will be carved on the cover: ‘For love, open with care.’ ”

“But, Grandmother, why does seeking love have to be conducted carefully?”

“Because, Binda, there’s a cobra snake that also lives in the box, and if you go in too quickly — or with anger, or pride, or ill intent — you are going to be bitten.”

“But, Grandmother, there must be a way to avoid the cobra.”

“There is, Binda, but it takes a lifetime to fully learn it.”

Maura, Talina, Bolivia

I rode fifty miles on horseback into the southern Andes with my guide, Ismael, crossing the San Juan del Oro River forty times in three days. In Talina, a town of sixty-five people, I stayed with Quechua farmers: a father and mother and their three grown children.

Maximo and Maura’s ranchero dated back to the 1840s. The granary, which they offered as my bedroom, housed their saddles, harnesses, and oxen yokes, which smelled of earth and mold. It was more appealing than any hotel I had ever stayed in.

The family wanted to serve me dinner in my room as a treat, but I chose to eat with them by candlelight at a rickety old table in the dusty courtyard — beef jerky, corn, bread, and chicha (beer). After dinner one of the sons would play the guitar, and we would sing and dance under the stars.

It was Maura, the mother, who stole my heart. Because of the rocking motion of my horse, I had arrived in Talina sick with vertigo. For the next three days, as the world spun beneath me, she cared for me as only a mother can do, using an arsenal of Incan herbal remedies and tonics. She cured me!

Jo Bradshaw, North Island, New Zealand

At Lothlorien Organic Fruit Farm I spent the most time with Jo, an Australian who lived in the big house with her three children. Jo was a small, muscular woman with a shock of thick, curly hair and a warm smile. She was undoubtedly the hardest-working member of the farm, striding the land with hand clippers to prune fruit trees. No one — not even Dale, who had started the farm ten years before — could keep up with her when she gathered the harvests.

Jo had a wonderful getaway spot, a tiny space in back of the pottery shed. We liked to slip off there at night after the children had been read to and tucked into bed. We sat for long periods sipping wine or smoking grass, writing in our journals, and sometimes reading aloud to one another from a spiritual book called Das Energi. After a long day of harvesting fruit, we held each other, our muscles sore and bruised, and drifted in and out of sleep.

Lobstermen, Outer Hebrides, Scotland

In late October Willie MacPherson (left) and Peter Haggerty took me out on the Atlantic for a full day of lobstering. From dawn to dusk we skirted the banks of the Hebrides in an old wooden boat called the Golden August, throwing out and hauling in close to seventy wooden creels.

“Aye, there’ll be fewer lobsters these years,” Willie said, “what with the Russians scraping the bottom with mile-long metal nets.”

After a lunch of sandwiches and hot coffee, we rested with the motor shut down, rolling gently on the giant swells that lumbered in off the Atlantic. Willie pointed out the three tall islands of St Kilda, once home to what he called the “truest specimens of the ancient Celtic people.” They had developed giant toes, he said, to enable them to scale enormous towers of rock barefoot and steal the eggs of wild birds. The Crown had removed the last of them in 1947 and relocated them into warm apartments in Glasgow. “They all died within a few years of broken hearts.”

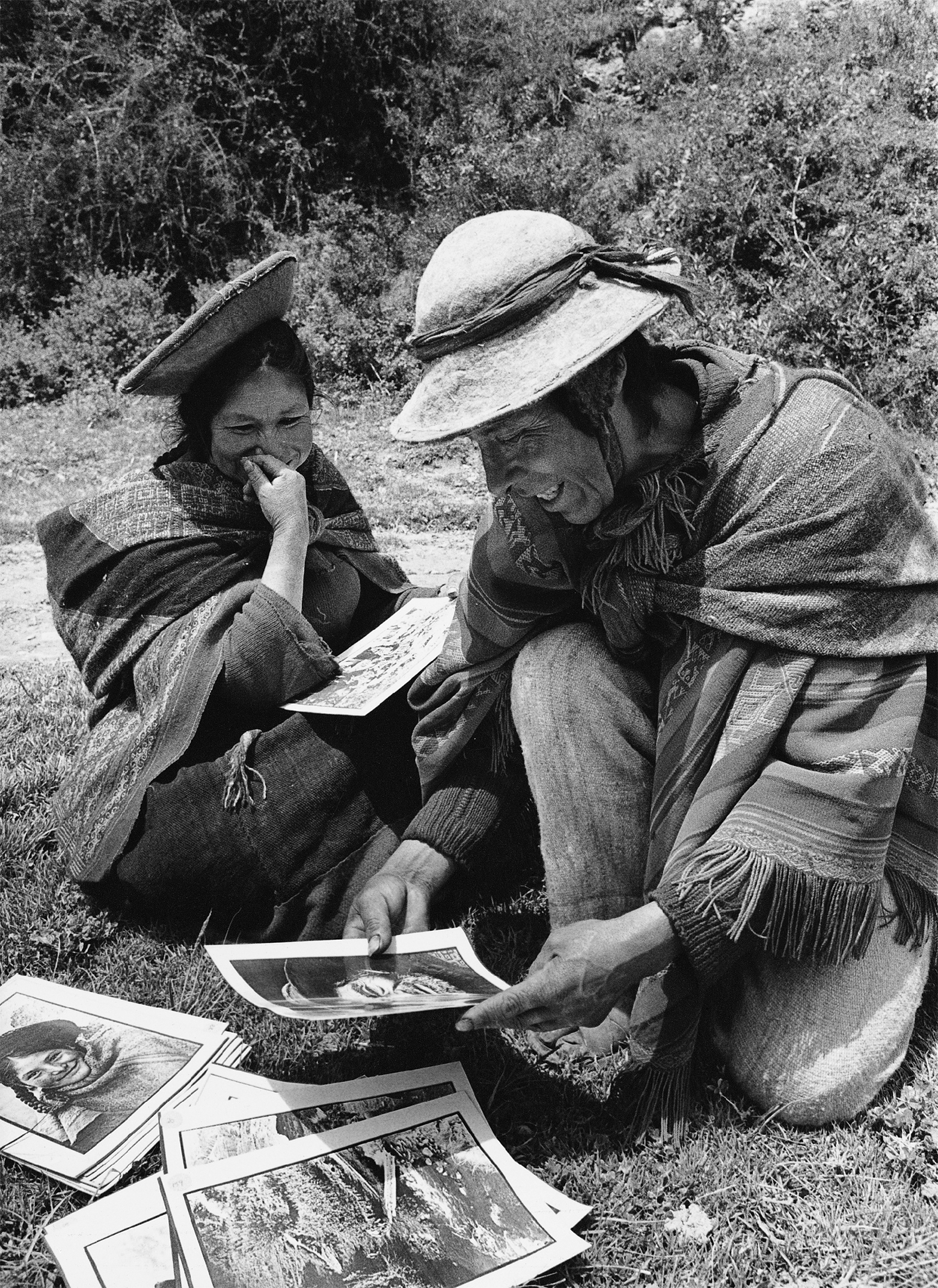

Ethan Hubbard in a Peruvian village

I returned to the Peruvian mountains for a final sojourn in 1991. My blue backpack accompanied me, as did a stout satchel containing two hundred portraits I’d made on previous visits, to be given away as gifts to the Quechua tribe.

The villagers were overjoyed when I began going from house to house. Most did not have pictures of themselves, nor of their parents or grandparents. I feel deeply blessed to have been able to bring such photographs to them and to people around the world. Pictures are remembrances of days gone by, telling the stories of our lives.