Buddhist mindfulness has gone mainstream, but not many people have heard of prosoche. That’s the ancient Greek word for attention, awareness, openness to everything, inner and outer alike. The Christian monks and nuns who resided in Egypt, Syria, and Asia Minor around 300 CE made prosoche a way of living. For Douglas Christie, a scholar of Christian contemplative practices, these desert fathers and mothers model an attunement and receptivity that is badly needed today.

Along with researching early Christianity, Christie has immersed himself in the writings of naturalists like Henry David Thoreau, John Muir, Aldo Leopold, Mary Austin, and Linda Hogan. His 2012 book The Blue Sapphire of the Mind: Notes for a Contemplative Ecology highlights points of intersection between nineteenth- and twentieth-century students of nature and third- and fourth-century Christian contemplatives. It also includes anecdotes about Christie’s personal efforts to establish a more “sympathetic participation” in the world. Though he was raised Roman Catholic and continues to identify with that denomination, he credits nature as much as religion for showing him, as an adult, how to be still, to listen in silence, and to pray.

Christie has been a professor of theological studies at Loyola Marymount University, a Jesuit school in Los Angeles, for twenty-eight years. In addition to Blue Sapphire, he’s the author of The Word in the Desert: Scripture and the Quest for Holiness in Early Christian Monasticism and The Insurmountable Darkness of Love: Loss, Contemplative Practice, and the Common Life (forthcoming from Oxford University Press). He’s contributed articles and essays to publications ranging from the Anglican Theological Review to The Best Spiritual Writing, and in 2001 he founded Spiritus: A Journal of Christian Spirituality. A husband and parent who long ago chose the householder’s path over that of the cloistered monk or wilderness recluse, he teaches courses with titles like “The Practice of Everyday Life” and “Contemplatives in Action.” In his recorded lectures on the Internet he smiles and laughs frequently, even when dealing with daunting subjects such as faith, despair, and the ultimate inscrutability of the divine.

For this interview we spoke on the phone, separated by thousands of miles. I started by requesting a description of Christie’s physical surroundings. He quickly sketched his garage office in Culver City (bookshelves, bikes, a couch), then went on to relate in detail the seasonal climatic nuances that define the Los Angeles Basin’s many neighborhoods. Was this nerdy academic thoroughness on display, or was it an expansive appreciation of his specific place, an acknowledgement that we’re always situated within concentric circles of belonging? Three hours later, after we’d talked ourselves nearly hoarse, I was convinced that it was both.

Douglas Christie

Tonino: I want to discuss the role of contemplation in our lives today — the ways you think contemplative practices can enhance our relationship with the rest of nature and potentially help us reckon with environmental issues. But first some history: What’s the tradition you’re building on here, and how far back does it go?

Christie: The historical sources of much of my thinking are found in the ancient Christian monastic tradition. I’m aware that Christianity can be a nonstarter for many people. I’ve been in settings with environmentalists or biologists where Christianity, and spirituality in general, is deemed nonsense. A certain secular sensibility finds it hard to see how religion could have anything whatsoever to contribute to pressing questions about society, the environment, and the like. So let me just say: I get that. Since childhood I’ve had an ongoing struggle with my own Catholic faith, and I feel like the critique of Christianity, in particular, is in many ways deserved.

Those caveats aside, I personally believe there is immense value in the ancient Christian texts and stories and the tradition of contemplation they establish. I believe they can be of great assistance to us as we navigate our complex, hypermodern world. On the surface that might seem a strange idea: that a contemporary person like me — living in Los Angeles, juggling family and job and the news cycle and the morning commute and all the rest — can find encouragement in the writings of Egyptian hermits who left their towns and villages along the Nile Valley in the late third and early fourth centuries and chose to dwell instead in the wild desert. Because that’s where this tradition I draw on begins. And from one angle, yes, its origins are a long way off and from a radically different historical moment. But there’s something of enduring value here.

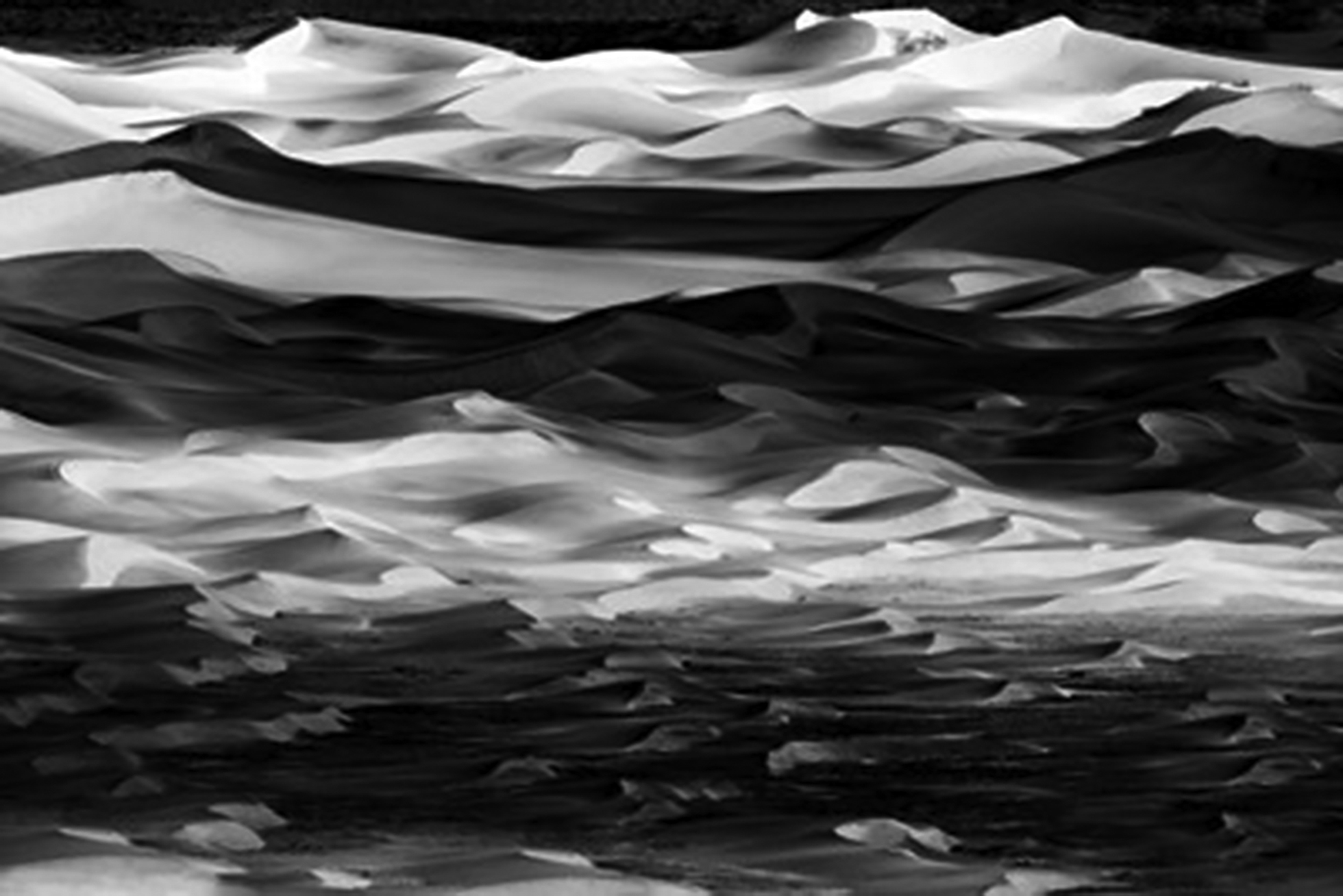

The early Egyptian monastic movement was complicated. Many of the monks formed communities and remained in close contact with the towns and villages of the Nile Valley. Others lived more solitary lives. And their beliefs and sensibilities were quite varied. But common to the different expressions of the movement was the idea of anachoresis — retreat or withdrawal — and a commitment to ascetic practices like fasting, sexual abstinence, physical labor, sustained meditation, and prayer. More than anything, there was a value placed on listening as closely as possible to the mysterious silence that supports existence, which is both the actual silence of the desert landscape and the silence of the self in contemplation. They listened to this silence with hopes of transforming their identities and reimagining community.

This early monastic movement rather quickly developed its own ethos, its own language, its own methods. And it gained a reputation. The abbas and ammas, the desert fathers and desert mothers, were seen as wise, courageous, and accomplished people, in no small part because of what they had suffered and struggled through in solitude, and they were sought out by other Christians for advice and instruction. There was a complex relationship between solitude and community. They lived not just alone in caves but often in a kind of neighborhood of fellow recluses, where they created experiments in communal living. And these experiments can still be seen playing out in the present moment.

That’s important to note: it’s a living tradition. The practices and ideals that came out of the desert 1,700 years ago were taken up by monks and nuns in the fifth, sixth, and seventh centuries all across Europe, and they spread from Europe to the New World, Africa, and Asia. There are Christian monastic communities all around the world today that trace their history back to the Egyptian desert.

Although I am not a monk — I wasn’t called to that life; I am married and have children — I’ve long found Christian monasticism compelling. I’ve not only studied this tradition but have participated in it: In my early twenties I wandered up the California coast to a place called Redwoods Monastery, a community of about a dozen women who are part of the Cistercian order, itself a thousand years old. The nuns I met there were sharing a life of silence in a forest of giant trees, living lightly on the land, caring for their place, and offering hospitality to those who happened to arrive at their door. Those nuns and those trees — they taught me to seek healing for my own fragmented life in silence. You could also call it prayer. You could call it listening. You could call it contemplation. Whatever you call this thing I found there, it’s been a lifeline for me. That early encounter helped me understand that I need to become more attentive, more still, more openhearted.

Tonino: Remaining in 300 CE for a moment: How did Christian monasticism originate? What was going on in the world just then?

Christie: During the past three or four decades there’s been a sea change in how scholars understand this period. For a long time there was a common narrative that the age of monks followed hard on the age of martyrs. We all know the story of the martyrs, or at least the Hollywood version: the early Christians were persecuted and crucified by Roman authorities for their beliefs until, in the early 300s under Emperor Constantine, Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire. There were those who found the martyrs’ single-mindedness and fierceness of devotion something to emulate. But the age of persecution was over. What to do? One response was to take up various ascetic practices, often in the empty, wild, desert places. The Greek word eremos, meaning “wilderness,” gives us our English word hermit.

There is some truth to this older narrative. There was an age of martyrs and an age of monks that followed. What’s changed is our understanding of why some men and women abandoned their towns and villages for this kind of life. What was going on socially, politically, and economically at the time? And how many other ascetic movements were active? These are questions we have begun to think about in a new way. In 1971 historian Peter Brown wrote a hugely influential essay titled “The Rise and Function of the Holy Man in Late Antiquity.” It caused quite a stir. Brown argues that one reason the monastic movement took hold was because of a kind of “social crisis” people were experiencing due to the crushing force of the Roman Empire, which exercised its power up and down the Nile Valley, often reducing its subjects to chattel. There were few avenues for ordinary people to claim their own agency or break free from the claims of Rome upon their lives. In response to this crisis, some withdrew to the desert. The Greek word for the monastic impulse toward solitude, anachoresis, is where we get the word anchorite, a synonym for hermit. This points, at least in part, to a kind of creative resistance to power that lay at the heart of the ancient Christian monastic movement.

This change in perspective helps us see these men and women as people struggling with pressures that are known to us today and that often make our contemporary lives difficult or untenable. It also suggests that whatever spiritual meaning we attribute to the rise of Christian monasticism should also take into account the social, political, and economic pressures that informed what it meant to engage in the act of anachoresis. It’s one thing to say the monks wanted to live lives of spiritual authenticity, like the martyrs before them. This is true. But it’s also important to recognize that withdrawing to the desert was a concrete survival strategy: to physically remove oneself from the reach of empire and reconfigure one’s daily existence out on the edges. The spiritual and embodied dimensions of this work are bound up together. The desert was a fertile ground for both.

I think this is partly why the monastic impulse remains so compelling to us now, despite the intervening 1,700 years. The desire to form community and live without succumbing to the social, political, and economic forces that threaten to undo us — isn’t this a vision that still motivates many of us? Early Christian monasticism is a model for the rigorous pursuit of a deeper ground of existence, something that can help us rethink the meaning of our lives amidst chaotic times, something that’s durable: silence, simplicity, self-discipline, solitude, community.

There was a value placed on listening as closely as possible to the mysterious silence that supports existence, which is both the actual silence of the desert landscape and the silence of the self in contemplation.

Tonino: Who were the abbas and ammas? What kind of people participated in this third- and fourth-century monastic movement?

Christie: Central to the early Christian monastic tradition is a text called the Apophthegmata Patrum Aegyptiorum, or The Sayings of the Desert Fathers. It is a collection of stories and sayings about the individuals who adopted this radical way of living, people with names like Macarius, Poemen, Agathon, Evagrius, Sisoës. These are all men’s names, and there is no escaping the male-centered character of this and other early Christian monastic texts. Still, women played a significant role in the ancient Christian monastic movement, and the presence of figures such as Syncletica, Sarah, Melania the Younger, Melania the Elder, and others looms large within the development of early monastic thought and practice. Thanks to scholars like Laura Swan, Elizabeth Clark, and others who have written on women in the early monastic tradition, we are slowly beginning to retrieve their voices and a sense of their importance.

Initially these sayings and stories were passed around by word of mouth. Later they were recorded in written accounts, and eventually they became touchstones for an emerging vision of Christian monastic life and its distinctive approach to the practice of contemplation.

Many of the characters in the Sayings were simple folk: illiterate or semiliterate peasants whose wisdom was born of long experience in the desert. There is often a stark clarity to their voices and a spiritual authority arising in part from their deep familiarity with silence. Other early figures in the tradition had received a rich education prior to their withdrawal to the wilderness, and they brought their intellectual training to bear on their radical new mode of life. The mix of backgrounds makes for a complex spiritual movement. We have these so-called ordinary men and women with little formal education sharing their lives with those capable of engaging Platonic philosophers in sophisticated dialogue. Together they gave birth to a brilliant and compelling vision of life born of disciplined attention to silence.

Tonino: Is there a historical figure who is emblematic of the contemplative tradition?

Christie: Almost all the literature looks back to the late third and early fourth century and a figure named Saint Anthony, sometimes referred to as “Saint Anthony the Great” or “Saint Anthony of Egypt.” He became famous in no small part because of a biography written by Athanasius of Alexandria. The Life of St. Anthony was one of the first early Christian biographies and became renowned in the ancient world. And it had a long afterlife, exerting a huge influence not only on many later contemplative writers and thinkers, but also upon artists such as Hieronymus Bosch, Matthias Grünewald, and Salvador Dalí, who found the monk’s struggle with demons in the desert — sometimes known simply as the “temptation of St. Anthony” — an irresistible subject for reflection.

As told by Athanasius, the story goes that Anthony was living an ordinary life in the Nile River Valley when his parents died, leaving him and his younger sister orphaned, but with an inheritance. One day he walked into a church and heard a reading from Scripture about Jesus telling a rich young man, “If you want to be perfect, go and sell everything you have and give the money to the poor. . . . Then come, follow me” (Matthew 19:21). What’s interesting is that Anthony took this to mean that he needed to go to the desert, to seek purification and transformation in solitude and silence. But it takes some time for him to get there. First he goes to a corner of his home garden. Then he goes to the edge of his village. Then he takes up residence in an abandoned fort, then in some tombs. In the tombs he experiences a sustained assault by demons so fierce and violent that he is brought almost to the end of himself.

In the ancient world demons were thought to be real presences, but I think, even then, they were also understood as profound psychological or spiritual forces — manifestations of wounds that are unhealed. We still use this language today: “I was fighting my demons.” Even if we don’t believe in the red horns-and-pitchfork devil, that language remains potent because we do appreciate that there are forces in our psyches with which we have to struggle.

So the story of Anthony becomes the story of a willing confrontation with these forces and a terrifying struggle to subdue them. This is what the paintings depict: not the holy, serene monk but the monk getting his ass kicked in the desert, scraping by with a tomb for a house, nothing between himself and the world, everything stripped away. For those raised Catholic, like me, what you see in childhood is mostly the saint lifted up, glorified. All through ancient Christianity, however — and especially in the case of the desert figures like Anthony — there’s this intense vulnerability, this distress, this sense of loss, and it’s so recognizable, so human. Being brought down into the depths of oneself — it’s honest. Somehow it helps.

I think this accounts in part for why Anthony became such an influential and compelling figure, both in the ancient world and later on. He embodies that aspect of this reality we’re so often embedded in, the suffering and struggle and unknowing that overtake us and leave us feeling helpless and bewildered. That he somehow survives this crucible and emerges as a figure of compassion and tenderness, a guide for others moving through the abyss, means so much.

Early Christian monasticism is a model for the rigorous pursuit of a deeper ground of existence, something that can help us rethink the meaning of our lives amidst chaotic times.

Tonino: What specific practices did the desert hermits engage in?

Christie: Silence is a big part of it. The experience of silence in the ancient Christian tradition is hard to grasp, though. There are sayings about the virtue of remaining silent, but silence itself, as it was practiced, is not completely accessible to us. It is by definition mostly hidden from view. I’m tempted to say it’s like a field of energy that grounds everything and that you sense as you descend into it. I think you can sense it as you read the Sayings — the feeling that the words of an abba or amma are arising out of silence, then receding back into it. What remains of the ancients is just their words — their silences are irretrievable — and that’s sort of ironic, because they were dedicated to remaining quiet. Anthony said, “Control your tongue and your belly.” Another of the Sayings refers to a hermit who kept a stone in his mouth for three years in order to learn silence. This strange practice signals how seriously the monks regarded the need to take care with the words they spoke. “Slander is death to the soul,” said one of the elders. Entering silence could help one avoid this and learn to listen more deeply and speak from a place of genuine regard for the other.

We’re such linguistic creatures — look at you and me, yakking away. In a world of noise it’s easy to underestimate the power of silence, which can be the ground that gives rise to a deeper understanding of the self, the world, God. My study of this tradition has inspired me to spend more time in desert landscapes, those physical environments where silence is a palpable, undeniable presence. But it has also led me to recognize and value silence and stillness in my own life, with my children, my wife, my students.

Ask yourself: Am I able to identify some ground of silence that has helped me? Where have I sensed that silence? Was it in the natural world? Was it while looking at a wild animal? Was it in my social life or in a relationship with someone I love? Most of us probably know the fraught, brittle kind of silence that comes up between two people, but what I mean is a kind of patient attention, a receptivity to what might emerge if we could simply shut up for five minutes; if we could resist the urge to fill every last space with me.

Silence and stillness can quiet us and enable us to really hear. That’s central. The ancient Greek word prosoche is usually translated as “attention,” and it’s aligned with the notion of mindfulness. Prosoche is our capacity to keep paying attention and not allow ourselves to fall into endless distraction. It needs to be cultivated through meditation, prayer, and the like. It was cherished by the desert monks, but it was a challenge for them, too. Distraction — the struggle to face and respond to the persistent presence of angry or resentful or selfish thoughts — was a very real part of their experience.

OK, you might say, but what are we learning to pay attention to? In religious terms, the answer might be God. Or the answer might be the deepest thing in me, in you, in the world. Or the deepest sense of connection and relationship. It’s a desire to open myself to the depths. At the end of the day, I don’t think it makes much difference whether you label those mysterious depths “God” or “the whole” or whatever else you please. It goes beyond names. None of this necessarily has to get attached to specific theistic notions.

But back to the desert and what contemplation really looked like in practice: The monks would often relinquish their possessions and enter the silence and stillness of the wilderness. There they would seek to hear and see themselves more clearly. They would observe thoughts, paying particular attention to those rooted in fear and pride and anxiety that stood between them and God — and between them and others. They would meditate on a word or a phrase from Scripture. They would alternate between fasting and eating very little. They would work with their hands, weaving palm fronds, making baskets or ropes. And sometimes they would engage one another in dialogue about how best to handle temptation and distraction and the life of solitude.

Something similar to the Zen tradition of the master and the disciple existed in the Egyptian desert — a pattern of seeking guidance from an elder, an abba or amma who has more experience, who has been there before, so to speak. When you are trying to pay attention to your life and not to hide from it, a teacher can help you see yourself more clearly. A lot of the exchanges in the early literature start with a question: “Abba, Amma, please, will you speak to me a word?” On the surface the question feels generic, formulaic, but there’s often a sense of urgency in it, a sense of lostness or uncertainty or hunger for something that can’t be named. And the elder’s response is almost never generic, but instead a compassionate reply fine-tuned for this specific person, this individual in need who is struggling.

This relational, communal aspect of contemplative practice moves me. It would be too easy to mistake this whole tradition as nothing more than a bunch of introverts drawn to solitude, battling their personal demons, subjecting themselves to too much sun, too much quiet, too much hunger and thirst, too much isolation. But this obscures the deeply relational character of this movement and the lives of those who entered the desert. Saint Anthony, after his long, lonely struggle, was found in the tombs by his friends, who tended to him. And later he tended to them. The search to know the self — that deepest thing in me, which can’t be separated from the deepest thing in you — always opens outward into a relational reality, a shared space: something the later contemplative tradition called the “common life.”

How is it that the search to overcome our alienation from ourselves can also open up the possibility of deeper, richer relationships with all living beings, with all of nature? The hope with contemplative practice is that any healing that takes place within us can in turn contribute to a larger healing.

Tonino: In addition to studying the ancient Christian contemplative tradition, you’ve been a student of North American writing by naturalists and poets with dirt under their fingernails. What overlap do you see in the two subjects?

Christie: For several years, back in my thirties, I stopped reading explicitly theological or spiritual texts altogether. Something was shifting in me, and I found myself able to read only poetry and natural history and ecological material. I was responding, I think, to a growing hunger to come home to my own body as a part of the world, and a recognition that I had been too long separated from myself. I partially attribute this to the overly dualistic spiritual teachings that I absorbed growing up Catholic: the idea that the body and the soul are somehow separate; that the spirit is supremely important and material reality less so. Such dualistic thinking is not in fact true to Christianity, which is deeply sacramental and reveres the material world as charged with the sacred. Still, it made its way into the Christian tradition, and I absorbed it into my own consciousness.

What the nature writers gave me that was critically important was specific guidance about how to pay attention to the living world. This was a turn away from abstraction and ideas. It’s fine to say, “We need to care more about nature,” but often, if you ask people what that means, it turns out there’s relatively little nature in their idea of nature. We need specifics: What do you care about? What other living beings are in your neighborhood? Is it your neighborhood, or are you just passing through?

Talking this way — promoting basic attentiveness to nature, to place, to the local — can sound sentimental and romantic, like something we haven’t got time for in an era of acute global climate change. We’re en route to the scary future, and learning to pay more-careful attention to animals and streams and trees isn’t going to cut it. Or so it seems. To an extent I agree: attentiveness alone won’t cut it. But even as I’m making adjustments to my life, trying to shrink my carbon footprint, exercising my political-environmental responsibility, there remains this other task that I dare not neglect: of cultivating intimacy with the natural world that I inhabit. We need to love the world not in the abstract but in the particular. We need to love the details.

That’s where following Thoreau, John Muir, Mary Austin, Barry Lopez, Annie Dillard, Linda Hogan, and others like them can lead us. Reading them, I began to feel my sensibility shifting. I noticed that I was moving a little slower outside, paying closer attention, delighting more in what was around me. Delight has to inform our environmental work. How could it not? Apprenticing yourself to this or that teacher who can help you feel the natural world more deeply — and feel yourself in the natural world — is one of the great spiritual challenges of this era. I use the word spiritual intentionally there. This is about connecting the deepest part of you to the deepest part of the world, and if that isn’t spiritual, I don’t know what is.

Tonino: There’s a huge emphasis on the importance of place in contemporary nature writing. How did the early Christian monastic tradition relate to place?

Christie: That’s not an easy question to answer. On the one hand, the desert itself doesn’t show up much in the ancient texts — or, at least, not in the way it would for a nature writer. On the other hand, we know that the desert fathers and mothers weren’t as cosmopolitan as we are. They lived out on the edges of the Egyptian desert. Some settled near the Red Sea. They were inhabitants of specific places like Nitria and Wadi El Natrun. They don’t talk explicitly about the flora and fauna, the weather and topography, but they were inhabitants of these places, and they knew them intimately.

Tonino: Charles Bowden, a favorite author of mine who lived in the Sonoran Desert of Arizona, once wrote, “We tend to see deserts as a quality more than a place. To go off into the desert in our language means not to visit a locale, but a state of mind.”

Christie: A state of mind and a physical reality at once. The two were inseparable for the early hermits. A famous line from the Sayings goes: “Sit in your cell, and your cell will teach you everything.” The cell is a place within a place.

This sense that a sustained commitment to place can yield wisdom also surfaced in the Benedictine tradition, which grew out of the desert in the sixth century, especially in the idea of conversatio morum: fidelity to monastic life in a specific place. It’s based on the idea of conversion. In a religious context, we usually think of conversion as what happens when you turn toward God and are reborn, but conversatio morum meant that a person entering a monastic community was entering this community, situated in this place, along this river, under the shadow of this mountain. The nickname given to the monks in some parts of the Benedictine tradition is “lovers of the place.”

My own feeling for this reality has been deepened immeasurably by spending time in monastic places. I’ve made pilgrimages to Saint Catherine’s Monastery at the foot of Mount Sinai in Egypt. I’ve gone to Mount Athos in Greece, a craggy, wild peninsula that juts into the Aegean Sea, where there are more than a dozen monasteries. I’ve visited the monasteries in the Wadi El Natrun near Cairo. Two summers ago I finally made it to Skellig Michael, a rugged island off the coast of County Kerry in Ireland, where a handful of monks dwelled in stone huts in the eighth century. These are powerful places. So, too, are the traditions of spiritual practice that ground the lives of those who inhabit and inhabited them. Leaning up against one of the beehive cells on Skellig Michael, I paused and listened and considered how it must have felt to get up every day and go to bed every night under these skies, along this wild coast, in the company of gannets, puffins, and grey seals. To pray in that place and to feel the force of it enter your deepest thoughts and feelings. In encountering these places, I think anew of my own place and the attention and care I am being called to give it.

Christianity has a lot to answer for, especially those parts of the tradition that have encouraged a sense of detachment from the body and the earth. Nor do I want to idealize the monastic tradition, which has sometimes neglected to incorporate the living world into its deepest values. But I can’t help feeling that these ancient spiritual traditions have something to offer us — a concreteness, a simplicity, a groundedness that is absent from so much of contemporary life. A similar impulse to the one that drew men and women into the desert in the third and fourth centuries continues to draw people into monastic spaces today, both in the hearts of big cities and out in the forests, mountains, and deserts. I believe that a desire for groundedness, getting back to the real foundation of our existence, is a significant part of that impulse. Of course, then comes the challenge to learn your place and tend to it. I’ve seen that effort expressed again and again by monastic communities — often enough to make me think: OK, here’s a hopeful model for how to be part of a place.

Tonino: The word contemplate, at least the way we tend to use it these days, implies an object. You contemplate your future prospects, a piece of art, your own navel. Places strike me as handy objects of contemplation: they’re always available, wherever we go.

Christie: Yes, we need to start with what’s immediate and particular, with what’s here. The Greek word for “contemplation” is theoria, and it means looking at things not only with the five senses, but also with the heart and mind. Contemplation is about learning to see, learning to behold the deepest, most encompassing reality. In Christianity the word for that reality was often God, but sometimes it was “the deep,” or “the night,” or “the real,” or “the whole.” This is a type of seeing that takes the world seriously on its own terms. You’re not trying to tell a symbolic or metaphorical story about the tree or the river or the sky. You’re allowing it to be what it is, without imposing on it, and you’re acknowledging that it has incalculable value and beauty and power. That’s the object of your contemplation. There’s no problem if you want to incorporate it into a personal religious system, and likewise no problem if you prefer to leave things indeterminate. In either case, contemplation is slowing down, getting quiet, allowing what you’re gazing upon to enter you, to shape you. It’s awareness of who we are in relation to the all, the whole, the immensity.

Tonino: The first essay of yours that I happened to read borrows its title, “Never Weary of Gazing,” from a passage by John Muir, who is arguably the poster boy for pairing Christian language with effusive praise of wild nature. In that passage Muir describes gazing at sugar pines, every one of which “calls for special admiration.” He’s lavishing his attention on them while sketching them in his notebook, feeling pained by the fact that he isn’t able to “draw every needle.”

Christie: Muir’s declaration that he never wearies of gazing is remarkable to us in a culture that treats so much as generic and, accordingly, disposable. The attitude is best expressed by Ronald Reagan’s famous statement that if you’ve seen one redwood, you’ve seen them all. Sorry, but, no, that’s preposterous. At this point it’s all too clear what this perspective — viewing nature as disposable, an inexhaustible resource to be used by humans — does to the living world. We have to allow our contemplative gaze to fall upon the particulars of the world, and that particularity can open up into something all-encompassing and awe-inspiring. It can, and it will. It must.

Why does our culture view counting the needles on a pine tree as something strange that needs to be justified or explained? Why is that seen as odd, transgressive behavior? Well, for one thing, because it’s not “useful.” It doesn’t accomplish anything. That’s the dumbed-down, utilitarian standard of Reagan: What’s the point of contemplating a tree?

I think we have to passionately reply that it doesn’t need to have a point. Contemplation is wonderfully purposeless. It avoids getting tangled up in utilitarian thinking and creates its own reality: you and that tree, its depths and yours. But it does indirectly accomplish something: If you allow your awareness to expand through prosoche, attention, you’re probably going to love the world more, and yourself in the world, too, and that’s going to inform how you meet specific challenges. There’s an ethic that emerges out of contemplative practice. But developing that ethic isn’t why you enter into the silence of the tree, why you rest your gaze on its needles in the first place. Put a different way: contemplation isn’t a means to an end, though it does change us.

It’s a false dichotomy to say, “Contemplation or action — take your pick.” Still, this debate crops up over and over again in the Christian tradition: Are you a contemplative, or are you actively engaged in solving problems? Contemplatives have been, and still are, routinely accused of being escapists who just go off and pray, leaving the hard work of alleviating suffering to others. In response, the Jesuits in the sixteenth century came up with a phrase that I’ve always loved: Simul in actione contemplativus — learning to be “a contemplative in action.” This can seem a utilitarian means to an end: Get your contemplative practice going, and you’ll soon reap the rewards of better activism! But the Jesuits meant it as more of a Zen koan — this rich, dense, single intuition about how learning to pay attention to something specific inevitably touches every facet of your life.

Of course, awareness is an ideal not many of us can easily achieve at the day-to-day level. But we do succeed sometimes, don’t we? Sometimes there’s no division between the awareness of beauty and our response to it, or the awareness of the deep need of another and our capacity to be present to that person. It’s all part of a single movement. I think we’re groping toward a language that allows us to honor that and value it.

Most of us probably know the fraught, brittle kind of silence that comes up between two people, but what I mean is a kind of patient attention, a receptivity to what might emerge if we could simply shut up for five minutes.

Tonino: In Blue Sapphire you point out that humility has its etymological roots in humus, meaning “ground” or “soil.” The word human can be traced back to the same source. Is it important to do away with pride and see ourselves as dirt, more or less, in order to experience a connection between, as you put it, the deepest part of oneself and the depths of the world?

Christie: I remember my father, when I was younger and he was still alive, trying to teach me, in his own inimitable way, that humility was important, that I shouldn’t let my ego create obstructions. In Christian spiritual thought and practice, right next to humility is self-abnegation, or even self-loathing: you make yourself low as a worm, because that’s all you are before God. That’s not the kind of humility most of us need, but neither do we need an inflated sense of our personal importance, because that, too, often prevents us from seeing and feeling the presence and beauty of other living beings. Many of us will say that every living being is important, but do we actually pay attention to them as if they have something to say to us — or, better yet, as if their presence alone, regardless of whether it benefits us, is worthy of our attention? Paying attention requires humility — a willingness to look across at others, rather than down on them. The point isn’t to say that humans don’t have our own distinctive gifts. But what does it mean to make room in our consciousness for the full reality of others? I doubt love can exist without humility; the ego will take up too much space, and you’ll fail to notice what’s before you. You’ll dominate the conversation.

Tonino: There’s silence again, right? Often the most humble thing is to be quiet. It’s a sign of respect not to bulldoze the moment with our own agendas. It reminds me of hiking and camping in the deserts of the American Southwest — how, at sunset, making even the tiniest sound or movement can feel almost rude.

Christie: As I said, in my thirties or thereabouts I felt a strong need to come home to my own body and my place in the world. I’d been living abstracted from myself, and it was the concrete specificity of things that called me back. I began hanging out with field biologists, people trained to be attentive to the life around them. Some of these new acquaintances were fantastically skilled bird-watchers. It was so humbling to go out with them into a forest or a marsh.

At first I had the completely wrong attitude, like: OK, I’m here. I’m ready for you, birds. C’mon, show up. Let’s do this. Ridiculous, I know. But I was impatient and unskilled at this particular way of paying attention. In time, however, I learned to shut up, open my eyes and ears, and patiently wait. The birds paid no heed to my designs and demands. And they did not arrive on my terms. But eventually they did arrive. And I came to experience that arrival as a blessing.

One time I was with a biologist in a wetland near San Luis Obispo, on California’s Central Coast. This guy had been monitoring birds there for about a year and knew the place well. He stood quietly, listening. Then he began scribbling in his notebook, recording all the action around him. Over the course of half an hour he identified more than two dozen species by sound alone. He had refined his capacity to listen. He was, it seemed to me, what Henry James called “one of those on whom nothing is lost.”

There’s something analogous in the practice of meditation or prayer. Anybody who tries entering into a space of silence can testify that, when you begin, you soon find you are out of your depth. You’re wanting things to happen, and quickly. The silence is all around you, yet you can’t seem to get into it, because your internal noise is locking you out. You’re unaccustomed to silence, and that’s uncomfortable. The only thing to do is to stay with it, be gentle with yourself, and return the next day, and the next.

My experience of learning to listen and look at the natural world has followed a similar course. One of my most important contemplative practices these days is taking a seat outdoors, maybe with a pair of binoculars, and waiting, listening, catching glimpses here and there of the wild world around me. Again, it’s hard to put a value on sitting around doing “nothing,” but it makes all the difference. It brings us deeper into the world, and then the world matters to us more.

Tonino: “Even amidst our continued and frenzied assault upon the living world,” you write, “we dream of the whole. The tenacity of the dream itself has healing power.” You seem to be saying that, regardless of the way things turn out over the coming years and decades, simply acknowledging this dream of wholeness can be powerful and positive.

Christie: This intuition that we are part of a whole — and the adjustments we make to our lives so that this intuition remains close — extends from third- and fourth-century Egypt up to today. It’s frequently spoken of now in scientific terms. One of the fundamental tenets of ecology is that the world of plants and animals and soil and water is a whole fabric, and that this fabric has integrity. It’s similar to the idea of paradise, or the garden, found in many spiritual traditions: the idea that, at the root of our existence, we belong to a pulsing, beautiful world, each of us bound to others by innumerable invisible threads.

Of course, we’re now experiencing deep tears in the ecological fabric, and we aren’t sure they will be repairable. Where does that leave us? I believe that having a vision of ourselves as part of a whole — recognizing that we can’t actually escape, and would not want to escape, how things really are — can inspire badly needed devotion. Even if the fabric is threatened, and perhaps especially because it’s coming apart at the seams, this vision has power.

The whole is not something separate from us, out there, a wounded thing for us to fix. We are it; it is us. And that’s not something to forget. In the face of so much turmoil, it can feel foolish to dream of paradise, of the garden, but what other dream is there for us? The desert hermits remind us that this dream runs deep, and poets can do the same. I’m reminded of the opening lines of a poem by Edwin Muir called “The Transfiguration”:

So from the ground we felt that virtue branch Through all our veins till we were whole, our wrists As fresh and pure as water from a well, Our hands made new to handle holy things, The source of all our seeing rinsed and cleansed Till earth and light and water entering there Gave back to us the clear unfallen world.

This is such a beautiful vision of reality. Even if it’s an ideal, even if I am not always able to conjure this vision into being, it gives me a feeling of possibility and direction and, yes, hope.

Tonino: It’s a rather mystical picture. Isn’t this what so much cutting-edge science is telling us, too — that we’re not the little isolated selves we think we are; that we’re more relationship than thing? Might mystical experience be just an ecological insight that’s fully felt?

Christie: Unfortunately, over the past couple of hundred years “science” and “religion” — I’m making quotation marks in the air — have come to think of themselves as antagonists. It’s an unfortunate divide because it can keep us from feeling these connections among different systems of inquiry. Religion can sometimes feel threatened by science, as if science could render it obsolete. Science, for its part, has a tendency toward reductive explanation and a lack of openness to what religion has, for millennia, presented as the broader picture of reality grounded in spirit. We could certainly do with a rapprochement between religion and science, a new line of dialogue. Debate is often tedious, because positions are already settled and nothing is going to change, but true dialogue is exploratory, provisional, open to new possibilities.

The two systems — ecology and mysticism — don’t really overlap very much in modern and contemporary discourse. Yet there are some deep affinities between them. The mystical points toward a collapsing of boundaries that are elsewhere taken to be hard and fast — most significantly the boundaries of one’s own identity. The mystic asks, “Where does the self leave off and God (or the All) begin?” In the Christian tradition mystical expansion is often an experience of love: the boundaries of the ego dissolve, and you’re able to give and receive love infinitely. Mysticism is about a sense of union, the idea that what we call “the self” is understood only when it is situated within a larger, more encompassing reality. Can we, should we, speak of a “mysticism of the natural world,” an evocation of the sense that our participation in the whole is something numinous and precious? And that this sense of belonging grounds our capacity to care for other living beings? Some already are thinking this way. But we need to go deeper.

Contemplation is slowing down, getting quiet, allowing what you’re gazing upon to enter you, to shape you. It’s awareness of who we are in relation to the all, the whole, the immensity.

Tonino: We talk of the inner life and the outer life, but I wonder if that’s a real distinction. Show me where one begins and the other ends! Yesterday I learned that a friend’s dog I’ve taken care of over the years was going to be put down. So I visited her, sat with her for ten minutes, put my hand on her soft ears, gave her a smooch, and cried, knowing I’d never see her again. What is inner and what is outer just then?

Christie: I agree that there’s too sharp a distinction made between what we touch and see and hear, and what we feel and think. It’s more of a continuum: we are shot through with the world. I mentioned the dualistic ideology, found in both religion and science, that separates mind and matter, spirit and body. This applies also to the way we separate the inner and outer, I think, and it’s probably done us a lot of harm.

We find ourselves in a dire predicament today, so alienated from the living world, from one another, from ourselves, yet also fundamentally so interdependent in ways we’re perhaps not aware of. We live in a moment where our inability to pay attention is part of what is afflicting us and, by extension, the environment. The solution is not running away from our bodies or neglecting our capacity to feel things viscerally in the physical world. And it’s not ignoring or downplaying our inner life. I think this moment is inviting us to a greater awareness of who we are in the world, which we sense ourselves to be a part of, and which we feel is whole even in its fragmentation. Silence, stillness, paying attention, being part of a place — the facets of contemplation we’ve been talking about are, I believe, part of the answer to the sense of alienation from the living world that is so much a part of this historical moment.

What’s beautiful about that story of you and the dog is that there’s no division there. As you’re petting her, bringing your face close, saying goodbye, you’re weeping. Why? What is that about? It has to do, I think, with the fragility of life, the beauty of two lives by chance coming together for a short time. When we experience loss and mourn, we have the capacity to maybe move toward a deeper way of living. It relates to our inner life, but it’s not separate from the physical: from the dog’s soft ears and that last look, your eyes gazing into hers. There it is: contemplation, death and life, inner and outer at once. If that isn’t a genuine moment of spiritual connection, what is?

Tonino: And it’s not uncommon. That’s why I mentioned it. That kind of moment is quite ordinary. Everybody I know has lost someone: a dog or cat, a parent, a sibling, a spouse, a child.

Christie: Yes, and it’s another invitation to open our boundaries, though by no means an easy one to accept.

Tonino: The Catholic author Carlo Carretto, who spent ten years living a life of prayer and work and silence in the Algerian desert in the mid-twentieth century, wrote, “But the same way is not for everybody, and if you cannot go into the desert, you must nonetheless ‘make some desert’ in your life.”

Christie: I love it — such a rich, moving idea!

Tonino: I suppose the question is: How does a person make some desert?

Christie: That’s a great question. And an important one. After his time in Algeria, Carretto returned to Italy to write and teach and help others in the pursuit of reflection and contemplation. He reminds me of another great twentieth-century figure of desert spirituality, Charles de Foucauld. Foucauld put in serious time in the physical desert as a hermit, but ultimately for his followers the “desert” ended up being in the chaotic, cramped cities, where they lived with the poorest of the poor, the bereft and suffering. Those cities couldn’t possibly have felt any farther from the sands of the Sahara, but Foucauld’s followers nevertheless managed to make them their desert.

A couple of years ago I was in Manila, in the Philippines, for a gathering comprised of vowed religious men and women from all across Asia. We were there to think together about how to respond to Laudato Si’, the great environmental encyclical of Pope Francis. While there, I met two members of the Little Sisters of Jesus, a group that claims Foucauld as its inspiration, and asked if I could visit them where they work and live. They brought me to their neighborhood: densely packed houses of corrugated metal and cardboard, open sewers, honking jitneys. They invited me into their tiny chapel, and we sat there together in silence for I am not sure how long. The sounds of the city poured down on us. We were far from any solitude. But for those few minutes, we inhabited a deep stillness. Then we rose and went outside and were immediately engulfed by children from the neighborhood, by neighbors and friends. I watched as hugs and kisses were exchanged, an impromptu soccer match broke out, and the sisters began engaging their neighbors in conversation, listening to concerns, responding as they could, making themselves present to those in their midst. Here were the disciples of Charles de Foucauld, drawing on this ancient desert ethos to live a life of humility, simplicity, generosity, and compassion amidst the urban commotion and noise and desperation.

What made it a desert? It was, I think, the intentionality these women brought to their work, the stillness they carried within them. Their sole reason for being there was to be open and receptive and responsive to their neighbors. It was everything to them. And there was such palpable joy in that sharing of life. Learning to live with such joy, such openness of heart, takes time. It takes silence and stillness, space in which we can learn to see ourselves, others, and our world. And it takes courage, opening yourself to love and be loved by others.

The desert as a school of love — that’s what I hear in that quote from Carretto. Return to yourself and recover your capacity for love. Make your own desert.