Since July 2021 married couple Monica Jane Frisell and Adam Scher have been traveling the U.S. in their “nomadic photo ark” — a converted cargo trailer with a film darkroom and a living space inside. At a time when the country feels divided, they are attempting to find evidence of what we share by making large-format portraits of Americans from different states and recording short audio interviews with them. People have proven eager to talk, especially coming out of the pandemic, when so many were isolated or felt unheard. Frisell and Scher say they are humbled by the stories people choose to share, and they hope to continue the project for the next three to five years. The following photos and interview excerpts are a sample of their growing collection.

— Rachel J. Elliott

Photo Editor

WeiWua, Willow, and FeiFei

Savannah, Georgia

FeiFei: I grew up in Savannah, but in January 2020 I was actually working in Shanghai, China. When the Wuhan virus started spreading there, I came back to Savannah and stayed with my parents. During the pandemic everybody’s life changed. For me, one of the big shifts was sitting still. In my previous job I traveled all the time. In 2019 I was on the road more than six months out of the year. Being stuck, literally not being able to really go anywhere, made me think, What are the things that really do make a life and make me happy? Being with my parents again and the idea of family. Also being still and finding peace within myself.

Last year I decided to become a single parent by choice. I had Willow with donor sperm.

Izzy

Green Mountain Falls, Colorado

My name is Isabella, and I go to Ute Pass Elementary School. I really like running and have since I was really little. I never did any club running until this year. Sometimes it’s a little bit difficult, but you pretty much let go after half a mile. It feels natural. You don’t really think about anything. You just kind of focus on your hands and your legs. You can look around and see where you’re going, but you don’t really think about school or anything like that.

I run at the middle school, and it’s with sixth-, seventh-, and eighth-graders, and it’s a lot different than just running in my living room. It’s nice to have friendly competition.

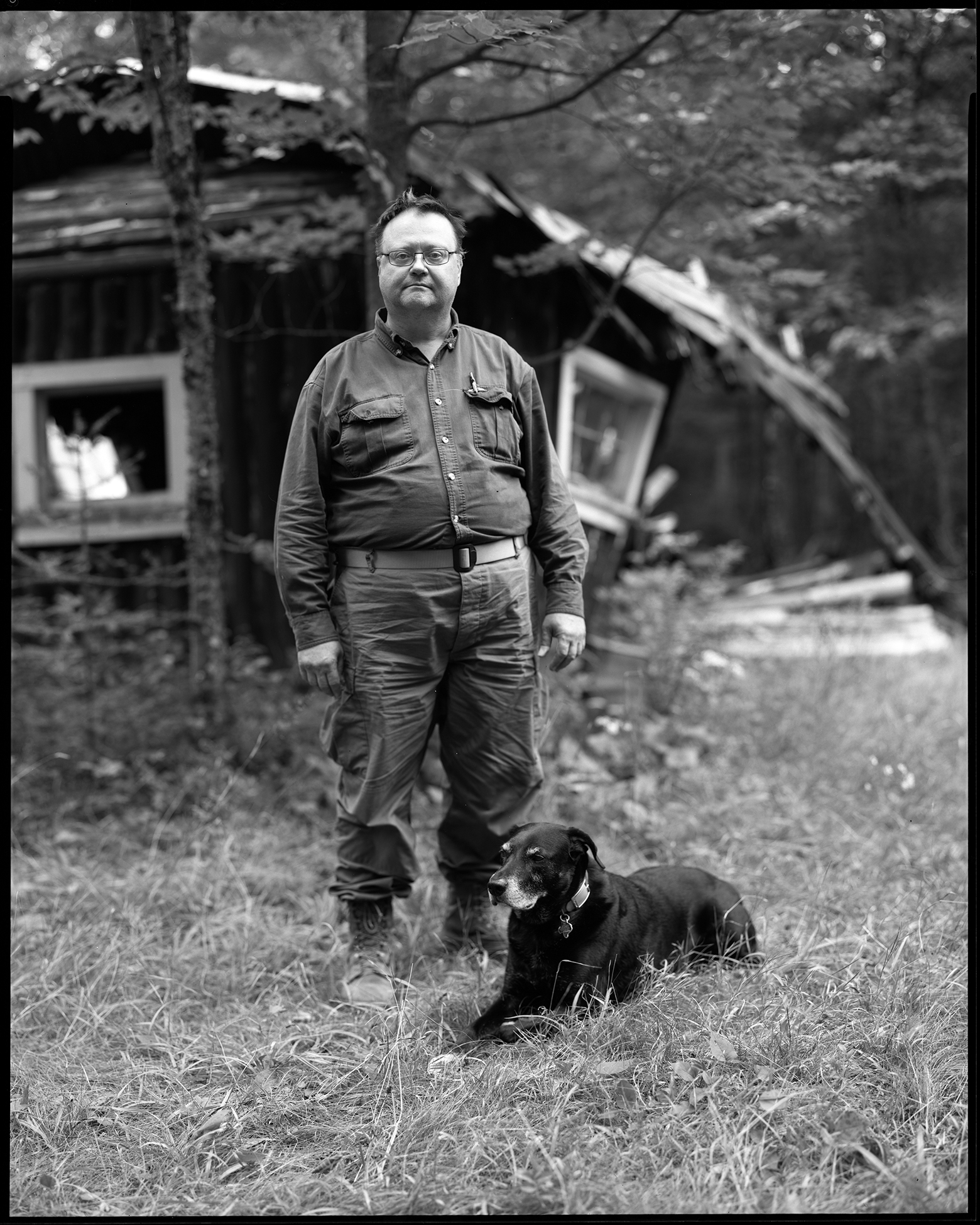

John

Two Harbors, Minnesota

This was a place that my grandfather and father took me to as a child. It is the first place I ever had to use an outhouse.

I would probably say that I learned all my outdoor skills here: how to blaze trails, how to navigate without a compass, how to split wood. I learned how to do carpentry with logs and build a deer stand. As I got older, I had such a sentimental connection to this place, and I didn’t want to lose these trails. Watching the cabin deteriorate, it reminded me a little bit about my mortality and about how I need to make sure I prioritize the things in my life that are important. It also really brought home how much I like being able to have the solitude of walking in the woods by myself or with my dog. It’s peaceful. I’m not looking at the clock.

Maurice

Savannah, Georgia

I wish I could think of something kind of smaller to share that wouldn’t make me cry, but the first thing that comes to my mind is I got sober almost thirty-six years ago. My brother, who is now deceased, was a drug-and-alcohol therapist. He took me into the rooms of Alcoholics Anonymous, and I came to grips with childhood trauma. The minute I came into AA, my whole spiritual perspective completely changed. It’s like the universe had just taken me from where I was ignorant, completely closed in, to being willing to embrace a new idea. At sixty-nine years old, I still have a long way to go to really embody who and what I truly am.

Mabel and Sam

Raleigh, North Carolina

As a school counselor, I get asked: “What made you want to work with kids? How’d you end up here?” I’ve reflected on it a lot. I had mentors, great teachers, and a great soccer coach and family. I don’t think, as a high schooler, I thought to myself, I’m grateful for these old folks. Maybe I should do the same. I think I just knew I wanted to help people in some way.

At the time I was a lot more religious. I actually went to school and majored in religion, and I went to a Christian school that I thought was going to help me to have all the answers of what God was like and what we should do, what’s right and wrong. Luckily it was the type of Christian school that does not try to make people have a very precise answer for all those things.

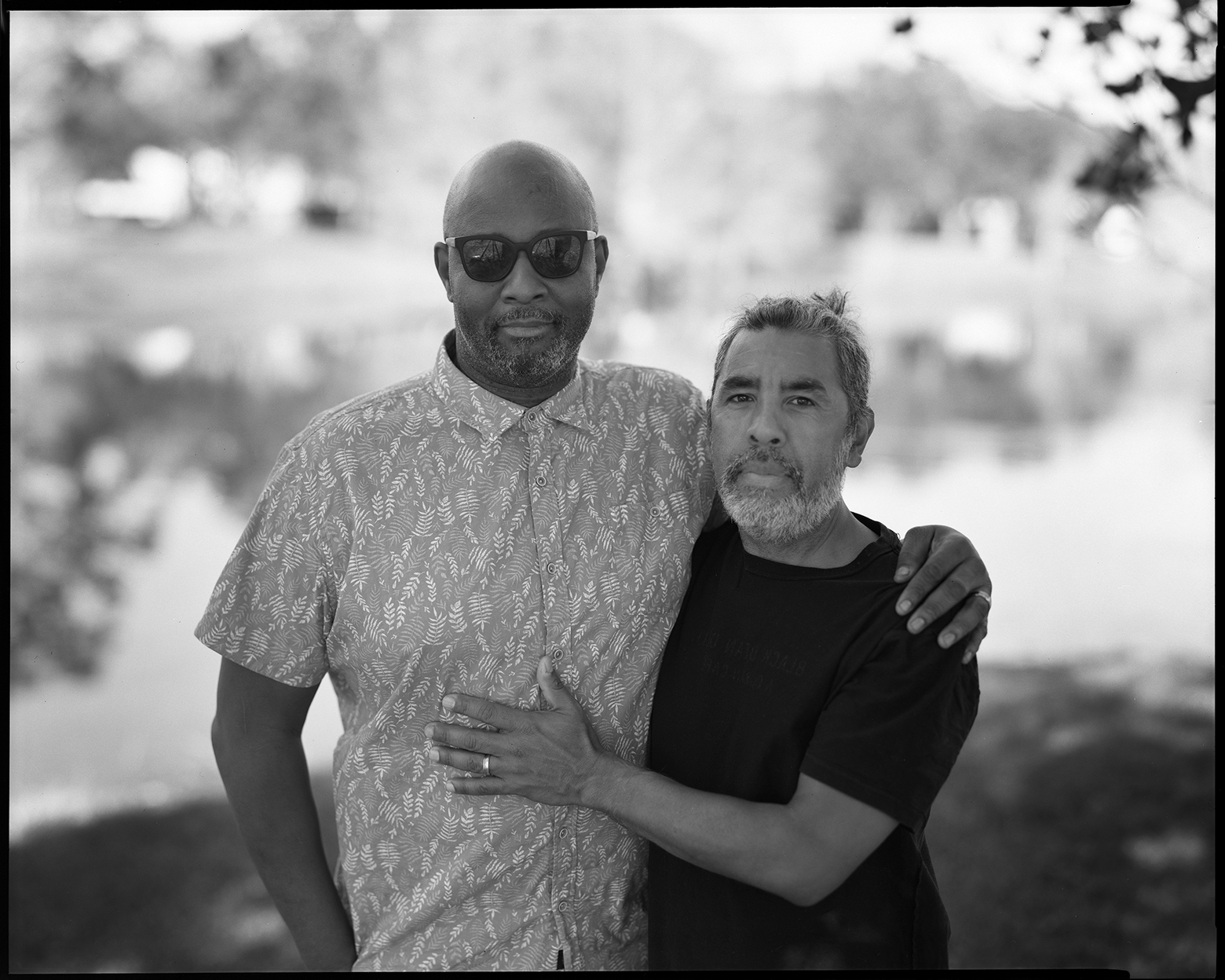

Ricardo and José

Winter Park, Florida

Ricardo: I joined the military back in October of 1989, completely on a whim. I wanted to leave Haines City [Florida]. There’s nothing there. I needed to explore life. And my sister went into the military. This was before “Don’t ask, don’t tell.” They asked you, “Are you a homosexual?” That was the first question. And then, “Have you ever had a homosexual experience?” Instantly I froze. These people know something; I’m going to get beat up. I wasn’t out at this time, but I answered both of them yes. Interestingly the recruiter came back to me and said, “I see on 25 and 25B that you answered yes. You might want to change those answers.” To this day I don’t know if he was an ally or just trying to make his numbers.

I moved into a world of being around a lot of males. I’d never experienced that before. It gave me a sense of belonging. These guys literally helped me get through basic training. I see why people are on teams — because of that camaraderie. Someone’s looking out for you.

My husband, José, and I met on Grindr. He is an asylum seeker from Venezuela. We have the most beautiful relationship, especially when it comes to communication, because there’s no room for being passive-aggressive. We both had worked on our demons before we met, so we didn’t come into this relationship wanting to fix each other. We still aren’t fixed, but we also are not looking to be fixed.

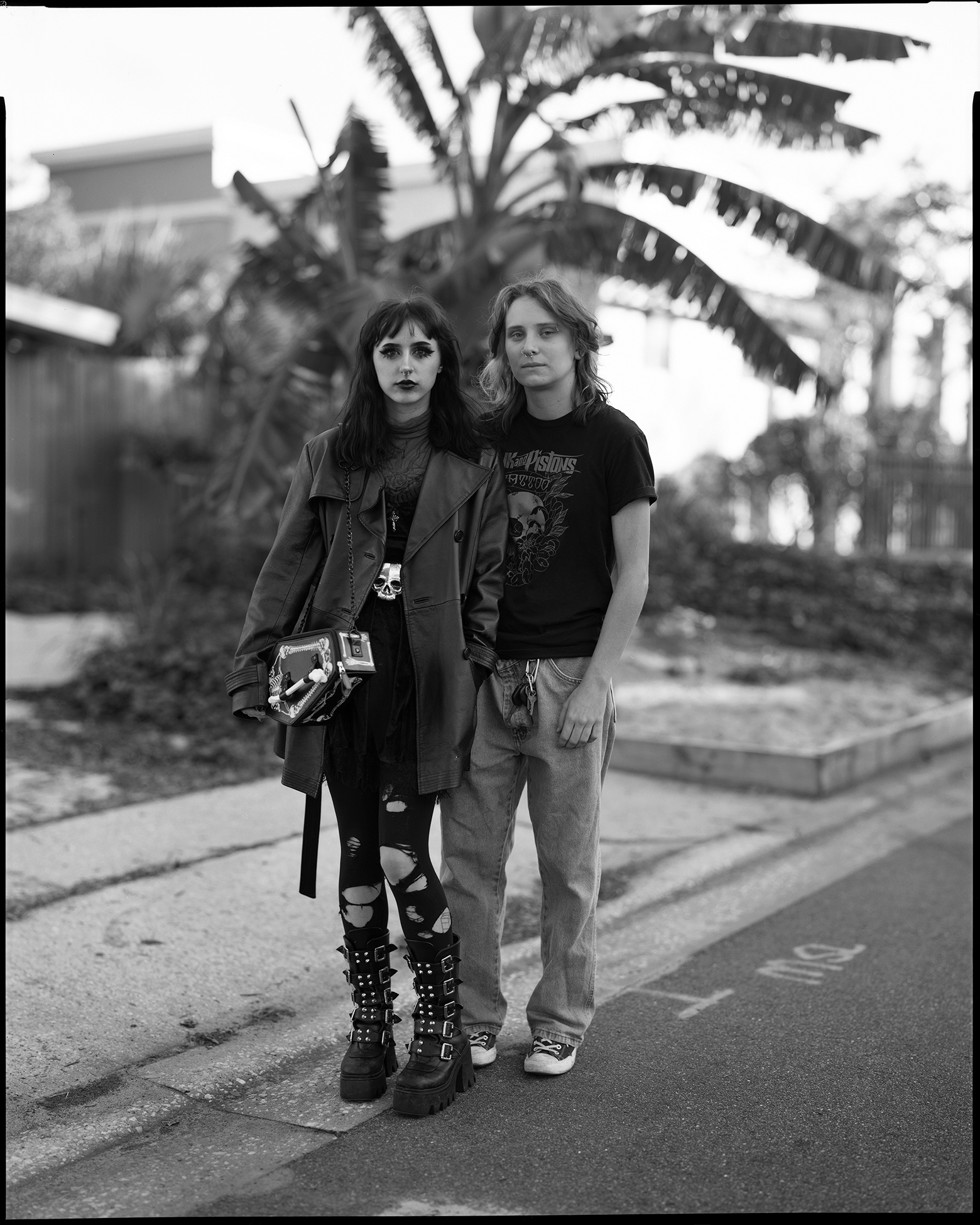

Juno and Peyton

Maitland, Florida

Peyton: In high school and growing up, I always wanted to get into music. I got a crappy amp and bought a bass off eBay, but I never really got to play it because my parents didn’t like it. That was about four years ago. Now I am in college in Orlando and going to shows. I have become close with a lot of local bands and started jamming with people I have met through the scene. We now have the biggest all-girl band in Orlando, which is really cool.

Juno: The most pivotal moment of my life, I guess, wasn’t really so much a moment as it was a string of decisions that kind of led me to start realizing that I’m allowed to take up space. I started dressing more unconventionally and getting more into the music scene and the goth scene. I found my people, and it’s a very supportive environment.

I guess my life really started to change for the better at the end of 2020, because that year kicked my ass. It pushed me to change and grow because I was really not doing well. I was hospitalized for depression. But being around people and hearing their stories made me realize that I have a lot to be thankful for. In late 2020 I started taking medication and going to therapy and seeking treatment. I started writing more. I’ve actually been writing a science-fantasy queer-fiction dramedy for the past twelve years. In a lot of ways it’s kept me alive. My characters have grown up and changed with me.

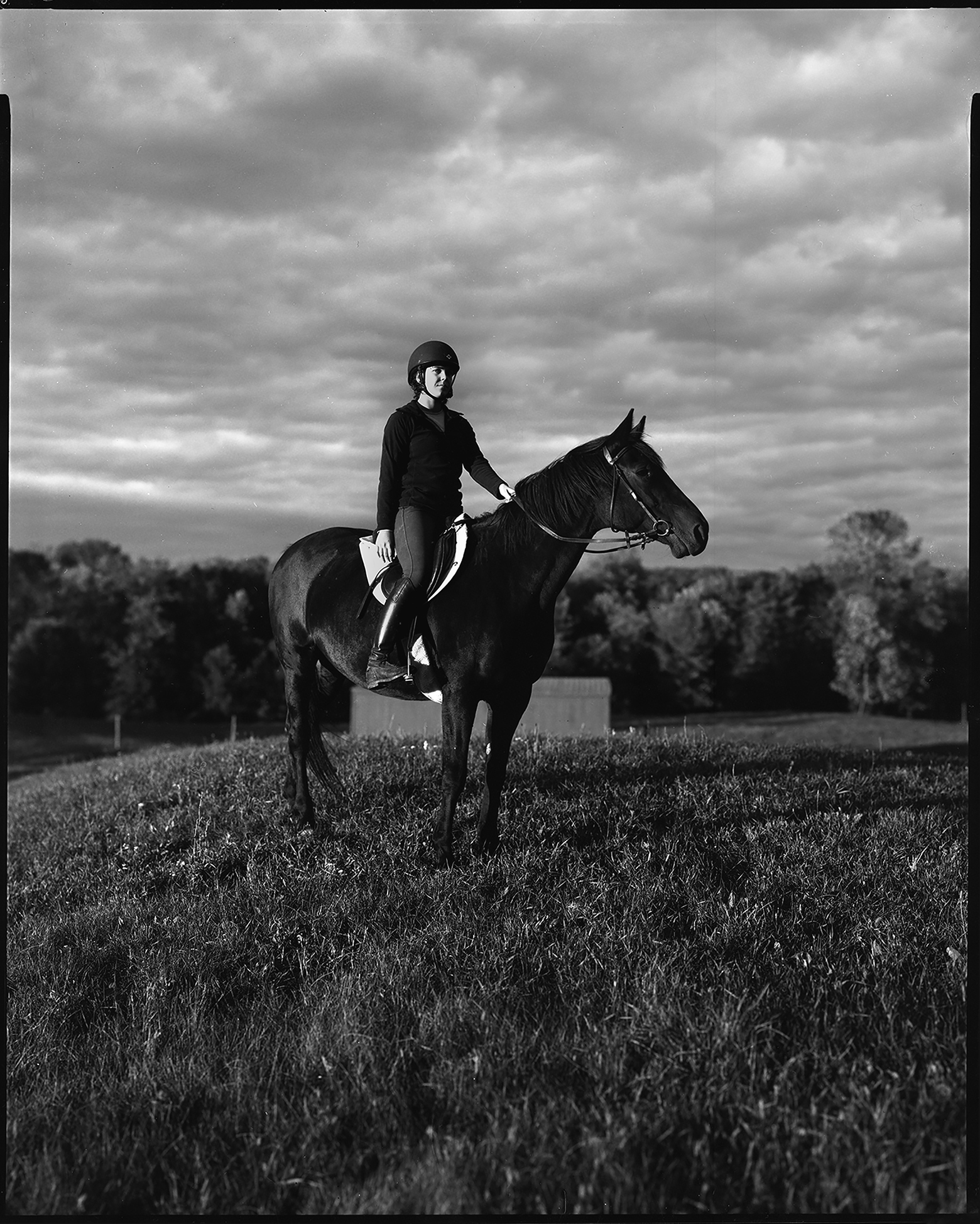

Saxon with Peazie

North Hero, Vermont

I think I always knew that I wasn’t a woman. My mom was very much a typical third-wave feminist, saying, “You can be whatever you want to be.” I tried really hard to follow in those footsteps and be my own kind of woman, because I didn’t have the language for anything else. It probably wasn’t until four or five years ago that I was like, I have the vocab for this, and, I cannot put myself in a box. I can sort of label my experience and find other people that are also experiencing this feeling. A lot of the reason that I came up here [to Vermont] is because I’m really tired of summers in the South. I didn’t want to do physical labor, riding five horses a day in 110-degree weather anymore. But I’m realizing that the other reason is I need a fucking break from all the antitrans policies [in the South]. Here they take me at face value and don’t care that I don’t always dress like a woman or that I don’t always look like a woman.

We always say, “Trans joy is resistance,” but I think trans peace is resistance.

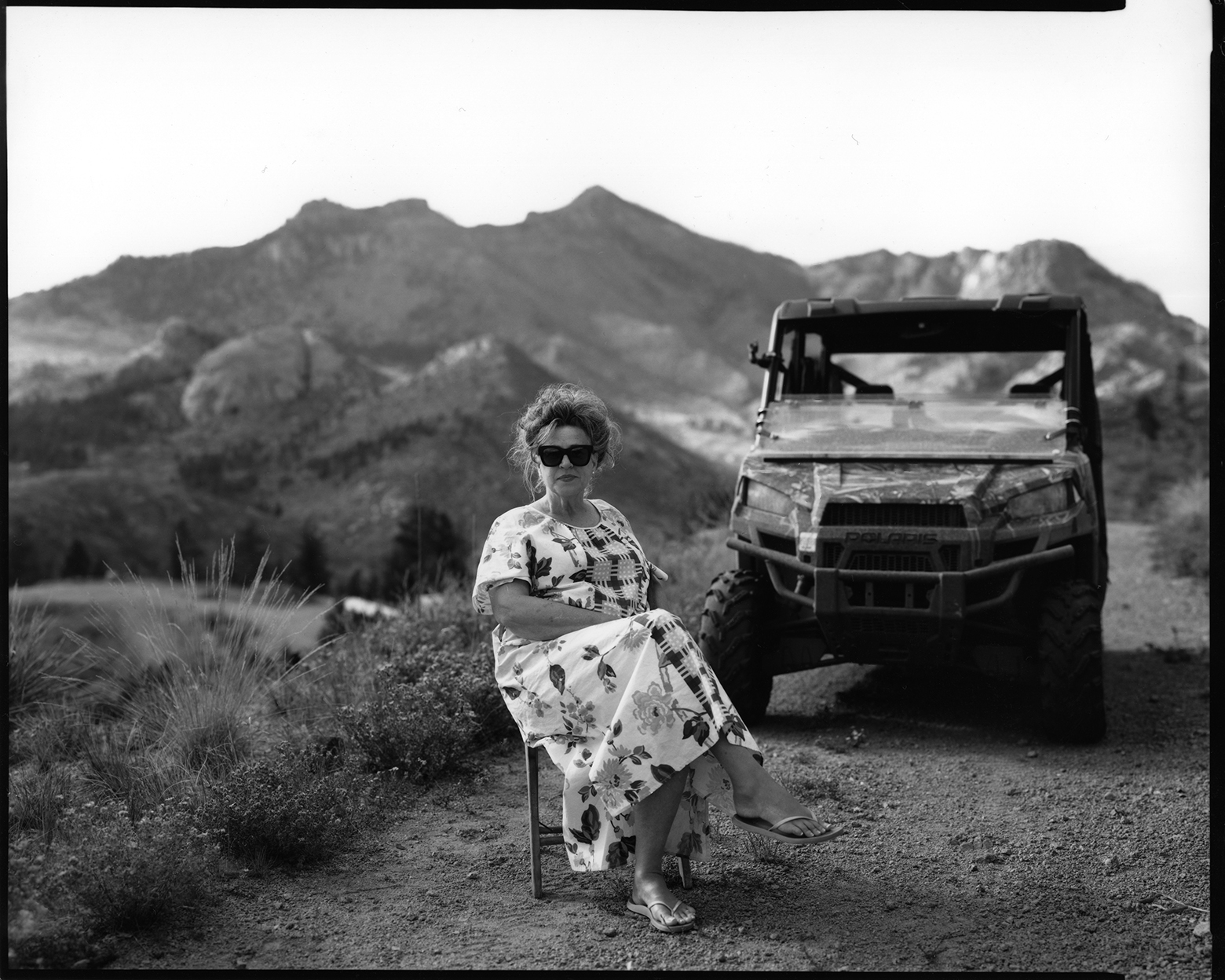

Tammy

Westcreek, Colorado

I was born in Oklahoma. I lost my mother when I was three weeks old. Her gallbladder burst when she was twenty-seven years old.

I’ve not had very much oversight, which has allowed me to be the best version of me, I think. But something that I’ve never been ambivalent about was having my own children. I felt that would be a really great healing process for me.

I told my grandmother, “I will have children even if I don’t have a husband.” And she didn’t like the idea of that at all. But as she got older, she caught on to it. Then I did meet the love of my life. We spent five years on the infertility track, which is a horrible roller coaster to be on. Every month you get your hopes up, and then they’re dashed. And what a wonderful thing to be able to afford and have access to a fertility specialist. It makes me sad that there are some women who want to have children and aren’t able to access that; it smacks of social privilege and makes me a little bit sick.

So we were lucky and spent all of this energy, time, and resources to get [pregnant]. The single scariest phone call was waiting to hear whether my eggs were too old and I was going to have to get an egg donor. I wanted to have a baby that was mine. The single most life-affirming, life-changing thing ever was having my twins. One of the boys was in the NICU for two months. One was in there for three. Every day, when he left work, my sweet husband came to the hospital to be with us.