We use cookies to improve our services and remember your choices for future visits. For more information see our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

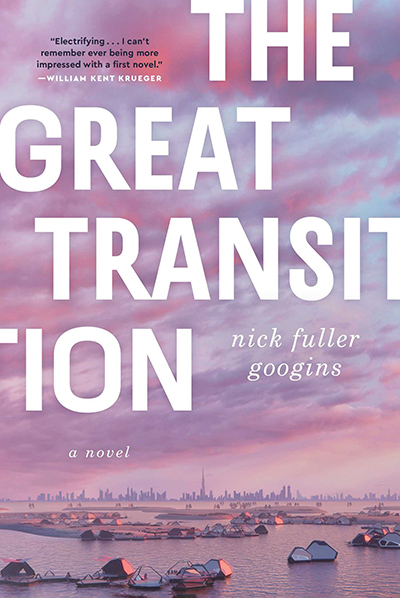

The Great Transition

An Excerpt from Nick Fuller Googins’s First Novel

We are pleased to share this excerpt from Nick Fuller Googins’s first novel, The Great Transition, published by Atria Books.

I was fifteen—same age as Emi—when the ocean saved me for the first time.

My father and I were harvesting kelp. Working the granite ledge at dawn. Wetsuits and goggles and knives. Plastic laundry baskets on the boat to collect the slick ribbons that we would dry and cut and package and ship. The early-morning sky was veiled in haze from faraway fires that had been raging all summer. This was the heart of the Crisis but hardly anybody called it that. It was just the world I had grown up in. Which is the only world that any of us know.

When I was eight Acadia burned shore to shore. We lived well north of the park but all summer the sun shone sickly through the haze. No stars. The blackberries my mother grew on a trellis by the drying huts turned sour. My parents and I were eating breakfast when the sky finally cleared. We had just sat down for oatmeal by the big kitchen window when it happened: a shock of blue so sudden we all stopped eating.

The winter I was nine we had record snowfall.

The winter I was ten it did not snow an inch.

When I was eleven there was a fish die-off in the Penobscot. Nobody knew why.

When I was thirteen the lobster disappeared.

When I was fourteen the puffins disappeared.

When I was fifteen the hemlocks disappeared. They had been fighting the invasive woolly adelgid as long as I had been alive. You could spend a whole morning crushing the tiny insects between your thumb and index finger and not clear one branch of one tree. I had to walk deep into the woods to find a healthy hemlock. One such walk I came across an emaciated moose calf on the ground covered in thousands of ticks. Some big as grapes. Moose were extremely rare then. This was partially why. The calf opened an eye like it was pleading with me: Do something. So I ran home and got our rifle and I did.

Ever since her school project Emi has been asking why we did not act sooner. Her mother has an easier answer. She grew up protesting with her family. Blocking oil trains. As for me, what can I say? My parents were loving people. Resourceful. Intelligent. They knew what was happening. My mother pointed out how the goldenthread blossomed months before the pollinators arrived. And the loons that used to winter on our shores—how long since we’d heard their ghostly calls? My father knew the tide pools better than anyone. He’d watched the Irish moss march south. Alaria gone north. He’d watched Laminaria longicruris—a kelp that prefers cold water—disappear in favor of sugar kelp, which likes slightly warmer shallows. He’d seen the last of the eelgrass.

So yes they knew. We knew. But I am asking for Emi—and not in a rhetorical sense—what more could we have done?

My family—like most families—was busy adapting. My father’s father had built our home with upcycled materials at the turn of the century. The house was a patchwork castle rising three stories out of the hemlock and pine. Each floor had its own woodstove. I remember that warmth. My mother reaching into cast iron with bare hands to turn logs and encourage embers. The glow on her face. Steam on the windows. The windows were not true windows but used glass patio doors my grandfather had sealed horizontally in place. For ventilation he had built a system of flaps into the walls to cycle out the damp maritime climate. But that climate had long since passed away with him—by the time I was fifteen our woodstoves were cold ten months a year. Instead of chopping wood we were assembling cisterns to collect rainwater. Installing solar. Digging a deeper well. Constructing tent platforms for the migrants coming north from the Gulf. We gave up on corn. Planted peaches. Dug two-tiered paddies for rice. We continued the family business: Wild Maine Seaweed.

My father and I foraged and harvested. My mother prepared. Her kitchen was her laboratory. Mortars and pestles and hanging scales. Little glass jars by the dozens. She had formulated seaweed blends that she packed in capsules to treat everything. Hypothyroidism. Weight gain. Heart disease. Gut health. Clients across the globe as far as Japan. She’d authored a cookbook. Seaweed soups. Dulse salads. Kelp noodles. Irish moss custard. Kimchi. Dashi. She kept a ball cap on a peg above the sink. She’d flip it backward for a hairnet as she worked and turn up the kitchen speakers and sing along to Dolly Parton and Valerie June and Taylor Swift. Everything about sharpening knives and seasoning cast iron and pickling and canning and caring for sourdough starter—all I know about food and cooking I learned from her. She was a resourceful, fun woman. Emi would have loved her.

The Crisis was economic ruin for our neighbors who knew nothing but lobstering. Lots turned to drugs. Some to suicide. For my parents however it was a boon because kelp contains iodine 127, which prevents the thyroid from absorbing radioactive iodine 131. This was important because the Turkey Point nuclear plant outside Miami had gone underwater. And the ocean had almost completely eroded the cliffs beneath the Diablo Canyon plant in California. And the San Onofre nuclear depository was leaking north of San Diego. And sunny-day waves were cresting the seawall of a plant near Houston. My parents had more demand than they could meet. And then my mother came down with a new strain of Lyme.

She spent all her kitchen time trying for a cure. Alaria-kelp reductions. Tinctures. Salves. When not experimenting she was in pain. Joints. Back. Head. Everything hurt. It was not a fun time. She slept a lot. Sleep was her great peace.

She was sleeping that morning when my father and I were harvesting kelp. Dawn slipping over the horizon. The ocean beginning its lazy tilt from low tide to high. Later with the Forest Corps I would learn more about wildfire than I ever wanted to know. At fifteen I never could have imagined the speed.

I was underwater cutting kelp. When I surfaced the sky had turned a glowing red and my father was gone. Just like that. I heard the whine of the gasoline outboard motor that was only used in emergencies.

The dead hemlock forest. It had gone off like a bomb.

The sky was flickering. Towering fingers of smoke and embers like an angry blizzard. And my father speeding right toward it. I watched him ground the boat. Run for the house. The smoke took him whole as the fire jumped to the shore in one rush. The fire made its own wind. And the sound: a roar like a freight train. Three hundred yards offshore and I could feel the heat on my face.

The fire announced its entrance to our house by shattering the windows my grandfather had sealed in place so many decades earlier— clear crystalline pops that met me as I stood waist-deep on the ledge. Embers and burning shingles sailed out on the fire wind to hiss and die in the cold water around me. I held a twist of sugar kelp in one hand. My knife in the other. I remember that. And the tide coming in. Like it always does.

Excerpted from The Great Transition. Reprinted by permission of Atria Books. Copyright © 2023 by Nick Fuller Googins.

NICK FULLER GOOGINS

© Amelia Mulkey

Nick Fuller Googins has published short stories and essays in The Paris Review, the Los Angeles Times, The Southern Review, and elsewhere. He lives in Maine and works as an elementary school teacher. The Great Transition is his first novel.

moreWe’ll mail you a free copy of this month’s issue. Plus you’ll get full online access—including more than 50 years of archives.

Request a Free Issue