My mother and I had been in the apartment four days when the sink broke and Zelensky came by to fix it. He had lived in the building for seventeen years — much longer than anyone else, as I understood it — and had some kind of arrangement where he helped out the landlady, who was unmarried, with basic maintenance.

The problem with the sink was the cold water wouldn’t turn off. It just gushed and gushed. I was home alone and answered the door, and there was Zelensky. He was old, seventy or so, the craggy skin and white hair and all that, but with blue eyes that were bright and alert. He wore a shabby gray sweater, even though it was June, and plain brown trousers, the kind you never see on anyone under sixty. In his hand was a big ring of keys; I guess he was just going to let himself in if no one had answered. He smelled like leather shoes and clove cigarettes and some kind of old-man aftershave, with a whiff of whiskey. On his head was a fedora, which he took off and pressed lightly against his chest.

“Good evening, young lady. I heard you were having some problem with your plumbing.”

“The sink. It’s like a gay-ser,” I said.

He cocked his head. “Ah,” he said, smiling broadly. “A geyser. Yes.”

He winked at me. No one had ever winked at me before. I thought it only happened in old movies. I was fifteen and knew what a geyser was. I’d just never had reason to say the word out loud before.

He didn’t even have a toolbox with him. He stood in the kitchen, watching the water run. He tried the faucet knobs, like maybe I was too stupid to have thought of that. Then he crouched down and opened the cabinet doors and moved some detergent and bleach around and started turning a knob or something on the pipe down there. The water stopped.

“Let me just check the basement,” he said, “but this looks no good.” His accent sounded European, but not French, which was the only other language I knew even a little. “Your mother is here?”

“No,” I said.

“And you are . . . ?”

“Eva.”

“Miss Eva,” he said. “I am Zelensky!”

He said this like he was announcing a circus act, ducking his head and doing a flourishy gesture with his hand. He smiled, so I guessed it was a joke.

“Nice to meet you, Mr. Zelensky.”

“No, no. ‘Zelensky.’ Just ‘Zelensky.’ I will be back.”

After he left, the place still smelled like him. I had been in the middle of watching The Lost Weekend and didn’t want to hit PLAY if he was just going to come back and make me pause it again. But it was an hour before he showed up, this time with a metal toolbox and a new faucet. My mother was home from her lunch date by then.

“Mr. Zelensky, I can’t thank you enough,” she said as he aligned the new faucet over the basin. “It’s times like this when a girl really misses having a man around.”

I slurped a Sprite in the doorway and rolled my eyes, even though no one was watching.

Zelensky said, “We’re not good for too much else at this age.”

My mother shot me a wide-eyed look and laughed.

“We outlive our usefulness,” he said, kneeling down and working a wrench underneath. “We do not die when we should.”

“Well, you’re certainly useful to us here,” my mother said.

“This is not so difficult. Someone told me when I was a boy that heaven is empty, the angels are all drunk in an alley somewhere, and it falls to people to be each other’s angels. So I am today your Angel of Fixing Sinks. . . . That should do it.”

He turned the faucet on and off to demonstrate.

“You must come over for dinner sometime,” my mother said. “I’m a firm believer in good neighborliness.” She stumbled a little on that last word. She often started sentences she thought were sophisticated without really knowing how to finish them.

“That’s a valuable quality,” he said.

I couldn’t tell if he was making fun of her or not. My mother insisted he wait while she went to get her datebook out of the bedroom.

“What happened to your father?” Zelensky asked me. He spoke quietly, gently.

“He died in a biplane crash in sub-Saharan Africa while filming a documentary on gorilla poaching when I was seven,” I said. This was true. Everybody always thought it was a joke at first — I even threw in all those details to make it sound more like a joke — but Zelensky only nodded.

“That must have been sad,” he said. “For a while.”

Then my mother was back, flipping pages and offering up dates, only to immediately rule each one out due to dinner with so-and-so or a party that some magazine was throwing. She had this habit of name-dropping people who weren’t as famous as she thought they were.

That little exchange with Zelensky about my father was there every time I passed him in the halls or on the street. It wasn’t like he gave any sign or regarded me with any special pity. It was just something he knew about me, and I resented him for it.

“That man’s got a story,” my mother said later. “He’s from Poland. He grew up during the war and was in a concentration camp.”

“Who told you that?”

“I’m a journalist,” she said. “I pay attention.”

I’m sure she’d heard it from the landlady, but she couldn’t just tell me that. She had to say, “He grew up during the war and was in a concentration camp,” like she was born knowing it.

I ran into Zelensky on the stoop the next day. I was going out to buy bagels, and he was coming back from his walk in the park. (He took long walks in the park every morning around seven, I soon learned, and the sound of him banging his door and creaking heavily down the stairs and whistling some old song I didn’t know became my own sort of alarm clock.) He wore his fedora slanted a bit to the side and a beige trench coat. He smiled at me until his eyes just about closed, like he was conceding some point I didn’t know I was making.

I glanced away and walked past him.

“There was a boy in the park pretending to be a horse,” he called after me.

I turned around and waited for the rest of the story.

“Then a real horse came by pulling a carriage, and he went back to being a boy.”

He chuckled until he started coughing.

“I gotta go get some bagels,” I said.

I don’t know why I always look away when people smile at me. It’s like they’ve caught me at something — being my stupid self, maybe. My black hair is cut in a shag, and sometimes I stick barrettes in it. I shop alone in vintage-clothing stores. My boobs have jumped three bra sizes in two years, and I furtively toss up prayers to a god I don’t believe in that they will stop before I turn into a hunchback. I wear big ugly glasses I picked out myself. I’m the kind of girl about whom people say, “She’d be so pretty without her glasses,” but I am not pretty without my glasses.

On my way to the bagel shop I tried to smile back whenever someone smiled at me, but every time I lost my nerve and stared straight ahead or at the sidewalk. At best I offered up this half-assed twitch at the corner of my mouth.

But here’s the thing: When I smile first at people, they all do the same. They all look away.

Our apartment was on the top floor of a five-story townhouse on the Upper West Side, right between Columbus Avenue and Central Park, that had been chopped up into flats around (I’m guessing) the turn of the twentieth century. As soon as we moved in, my mother started looking for spiders — before we unpacked, even. She went to every corner and opened every cabinet. The one in the closet she fwapped with a rolled-up New Yorker, giving a little squeal on impact, not out of squeamishness but out of fear she might have missed and the spider would leap onto her face and start biting. She didn’t miss; the spider was a flat brown smudge with crinkly legs, stuck to an advertisement for vodka. My mother studied her handiwork before throwing the magazine in the trash.

The one in the shower she just washed down the drain. Then we could start unpacking.

“Spiders eat bugs, you know,” I told her.

“Spiders are bugs,” she said. “And don’t give me that whole eight-leg-six-leg thing. It’s like hiring a serial killer to live in your bedroom to protect you from thieves and perverts.”

She pretended to find some glamour in the new neighborhood after ten years in the Village — we had been on West Fourth right off Hudson — but I knew the truth was we just couldn’t afford our bigger place in the Village anymore, not with all my father’s money pretty much gone and my mother having left a steady job as an editor for a fashion magazine to become a freelancer. She insisted our new apartment was in a landmark building, which I doubt, but it was one of a row of classy Victorians, painted pale yellow with a cherub face above each window and an old stone stoop that hooked around like an L. It reminded me of The Apartment or Breakfast at Tiffany’s.

I was big into old movies. I couldn’t finish a book to save my life, probably because words were my mother’s realm. She woke up early and wrote before breakfast. Except for one poorly received novel that I’ve never found in a bookstore (it was about a wife and mother whose husband leaves her to make documentaries in Africa), she wrote about “women’s issues.” She privately thought capital-F Feminism was over, and we (women) should all accept that our lives were better off with men around to take care of us. My father had left her a year before he died. In an article of hers I read on the Internet, she wrote that, in the months leading up to his death, he was sending her letters apologizing for what a cad he’d been and saying he wanted to make things right and would, just as soon as he got back from Africa. I’ve never seen those letters.

Summer had just started when we moved, and the few friends I had were off in Europe or South America or the Vineyard, so I spent most of my time watching old movies in my room. When my mother wasn’t writing, she was on the phone complaining about friend X to friend Y, or she was out having lunch with both of them, or she was knocking on my door asking if I didn’t want to go outside on this gorgeous day and take a walk in the park maybe. She suggested this not out of concern for my complexion but because I didn’t want to do it. Had I been the kind of girl who spent all day walking around the park, she’d have suggested I sit in my room and watch movies.

We had our own bathroom, but the other two people on our floor had to share a bathroom in the hall. They had apartments so small one of them didn’t even have a kitchen. In the morning I heard their doors opening and closing and the shower coming on. Each of them always tried to be the first to the bathroom. They were very polite about it, so I figured they hated each other. One of them was a young British woman who worked at the UN. She was petite and pretty, I thought, until one day I realized how beakishly pursed her lips always were, and from then on I always called her “the Duck.” She brought men home all the time, at odd hours. Sometimes my mother and I heard her having sex down the hall. Real sex didn’t sound like movie sex. (I’d never expected it to.) The Duck sounded like she was pleading to be put out of some kind of misery.

The other person on our floor, sharing the bathroom with the Duck, was Calvin. He was a college-entrance-exam tutor, midtwenties, sandy haired, sort of cute in that shy-guy way some girls like. My mother had him over for coffee when we first moved in and put on her writer act. I came out of my room after the end of Lady for a Night and found them on the couch. My mother was cracking up. I could tell from the way Calvin was smiling that she had done a wonderful job of making him uncomfortable.

“This is Calvin,” she said, as though we hadn’t had a dozen conversations about him being the only halfway handsome guy in the building. “Did you know he has a band?”

“I don’t have a band,” he said to me.

“You play music,” she said, slapping him on the arm like he was too modest for his own good.

“It’s just me and a guitar.”

“We’ll have to come see you play,” she said.

“I’ve only done a couple of open mikes.”

My mother was sitting close to him, half facing him. I sat down in the little armchair, pulled my legs up under me, and leaned forward to rest my chin on my hand.

“I bet you’re a big hit,” my mother said. “I bet the girls all go mad for you. Honestly, if I were just a few years younger!”

She laughed loudly. When she laughed, all her wrinkles bunched up. Calvin was smiling at the floor.

“Your mom said you like movies,” he said to me.

“I guess.”

“She only watches classics with dead people in them,” my mother said. “She needs fresh air. Calvin, you should take her to the park one day.”

He glanced at my chest, and I caught him. He started to stammer some response to my mother.

“I worry,” she said, “what it’s like for her to grow up without a man around. A mother can only do so much.”

“Well,” Calvin said, looking at his watch, “it’s getting to be about that time.”

It’s not that I want guys to look at my boobs. It’s more like a game: Will they look, and when, and how often? Can I stand or sit a certain way that makes them look?

The dinner party my mother kept mentioning to everybody finally happened in late July. Calvin was the first to arrive, with a bottle of red wine. He wore a blue button-down that went nicely with his eyes and brown corduroys that were just awful. My mother made a big show of opening the wine in three swift moves with this new gun-looking device she’d received as a perk for writing an article about how zinfandels were making a comeback.

“I hope you like halibut,” she said to Calvin.

She had made something that looked like lasagna but had fish in it. It smelled rank, but Calvin pretended not to notice. The Duck arrived with her own bottle of wine, and finally Zelensky with nothing but his hat in his hand. It was hard to fit all five of us at our round kitchen table, and I ended up in a folding chair between Zelensky and Calvin.

“It must be exciting to work at the UN, especially with a war on,” my mother said to the Duck, forking a lump of halibut. “I interviewed Madeleine Albright once.”

“I just help with scheduling,” the Duck said.

“Madeleine Albright wears fabulous shoes,” my mother said.

The Duck smiled. She had nicer teeth than I had been led to expect for an English person — pretty much perfect teeth, really.

“This is beyond delicious,” Calvin said.

“This is only the second time I’ve had fish,” Zelensky announced. His white hair fell in front of his face as he leaned forward to eat, and he swept it back with his free hand. With that one gesture I got this image of him as a young man in Berlin or Warsaw or wherever, and it occurred to me that old people probably don’t realize how old they really are. They just go on having the same mannerisms they’ve always had.

“But how can that be?” my mother said.

Zelensky took his time chewing. “I grew up on potatoes.”

“Were you really in a concentration camp?” I asked.

There was no sound except Zelensky chewing as he watched me. “Miss Eva, how old do you think I am?” He winked at me. “I used to live in Brooklyn,” he said. “Atlantic Avenue. I believe there’s a mall there now.”

“You can’t just ask people that,” the Duck said to me.

“Why not?” I said.

“Because . . .” She looked around at the others, amazed that she had to spell it out. “It’s a very serious subject.”

“She didn’t mean anything by it,” my mother said. “She’s just a curious girl. She gets it from her mother the journalist, I’m afraid.” She tittered nervously.

The Duck and Calvin exchanged a look.

“Anyway,” Zelensky said, “nothing very edible ever came out of the Gowanus Canal. In fact, the first time I had fish was when I was twenty. This was before any of you were born. I worked in a freak show in Coney Island. ‘The Great Zelensky.’ I could eat fire and swallow swords. ‘The Immortal Zelensky’!”

He did that circus-announcer thing with his voice that he’d done when he’d first told me his name. We all stopped eating and sat staring at the comically noble look on his face.

“I had to do this crazy kind of thing,” he said, “to support my sister until she found a husband. One day the Elastic Woman fried up some big fish that the Jigsaw — this was her husband; he was covered in tattoos — had caught on the pier. I was sick for three days. But this,” he said, stabbing at his plate with his fork and looking at my mother, “this is not the worst thing I’ve ever eaten.”

“Do you still remember how to do it?” I asked. “Can you swallow that knife right there?”

He looked down at the stainless-steel butter knife on his plate. “Miss Eva,” he said, leaning toward me a little, “I spent years forgetting how to do it. The magician is tired of tricks.”

An hour later everyone was gone, and my mother seethed as we did the dishes.

“Does it please you to make me look like an idiot? To ruin my dinner party? Nobody stayed for coffee!”

I was drying a plate. “It was just a question. He wasn’t offended.”

“Do you think this is easy?” my mother asked. “Do you think my life is one big fiesta?”

“Yes,” I said, “I think your life is one big fiesta.”

I sat out on the stoop while Calvin played his guitar and sang. He was really self-conscious about me watching at first, and I wasn’t sure where I was supposed to look: At him? At his fingers on the guitar? At the parked cars up and down the street? We were sitting at opposite ends of the top step, slightly inclined toward each other.

“Cool,” I said when he’d finished the song. It wasn’t that great, but he smiled shyly and tuned a string. He had dimples, and for the first time I understood why other girls found them cute.

“So, that dinner party,” he said.

“I don’t know why I asked him that. It really pissed off the Duck.”

He looked at me blankly.

“That British girl who has all the sex. I can’t remember her name.”

“Elizabeth,” he said.

“We call her ‘the Duck.’ ” He didn’t smile at that, so I said, “My mom’s got a thing for you.”

“Well.” He cleared his throat. “She’s just being nice. I’m a little too young for her.”

“Don’t tell her that. Oh, by the way, I made you a list.” My voice caught a bit when I said it. I gave him a folded-up piece of paper.

“What are these?”

“They’re my ten favorite movies ever. You should really see them. I own nine of them.”

“Thanks for the cultural education.”

“You should come over and watch one sometime.”

“That sounds fun.”

By what I guess might be called “coincidence,” I was heading out for a bagel early the next morning when Calvin came out of the Duck’s room. He was wearing the same faded Afghan Whigs concert T-shirt from the day before. We both stopped in the hallway and stared at each other. He smiled sheepishly.

“Hey, Eva,” he said.

He fumbled to get his key in his door, and I went on past him and down the stairs. Just before he closed the door, I let out a loud “Ha!” My legs were shaking. When I got outside, I wasn’t hungry anymore, and I sat on the stoop for like an hour, but nobody came out.

That night my mother got into some marathon phone conversation with an old sorority sister who lived in Miami. After about twenty minutes of her overenunciation and exaggerated laughter, I went out into the hall. That’s when I noticed something hanging from the ceiling near the other end of the hall. It was a little six-inch metal hinge, and it took me a second to realize I had never noticed it before because normally the trapdoor to the roof was padlocked, but now the padlock was gone, and the hinge hung loose. There was a ladder built into the wall, and I climbed it and pushed hard against the trapdoor.

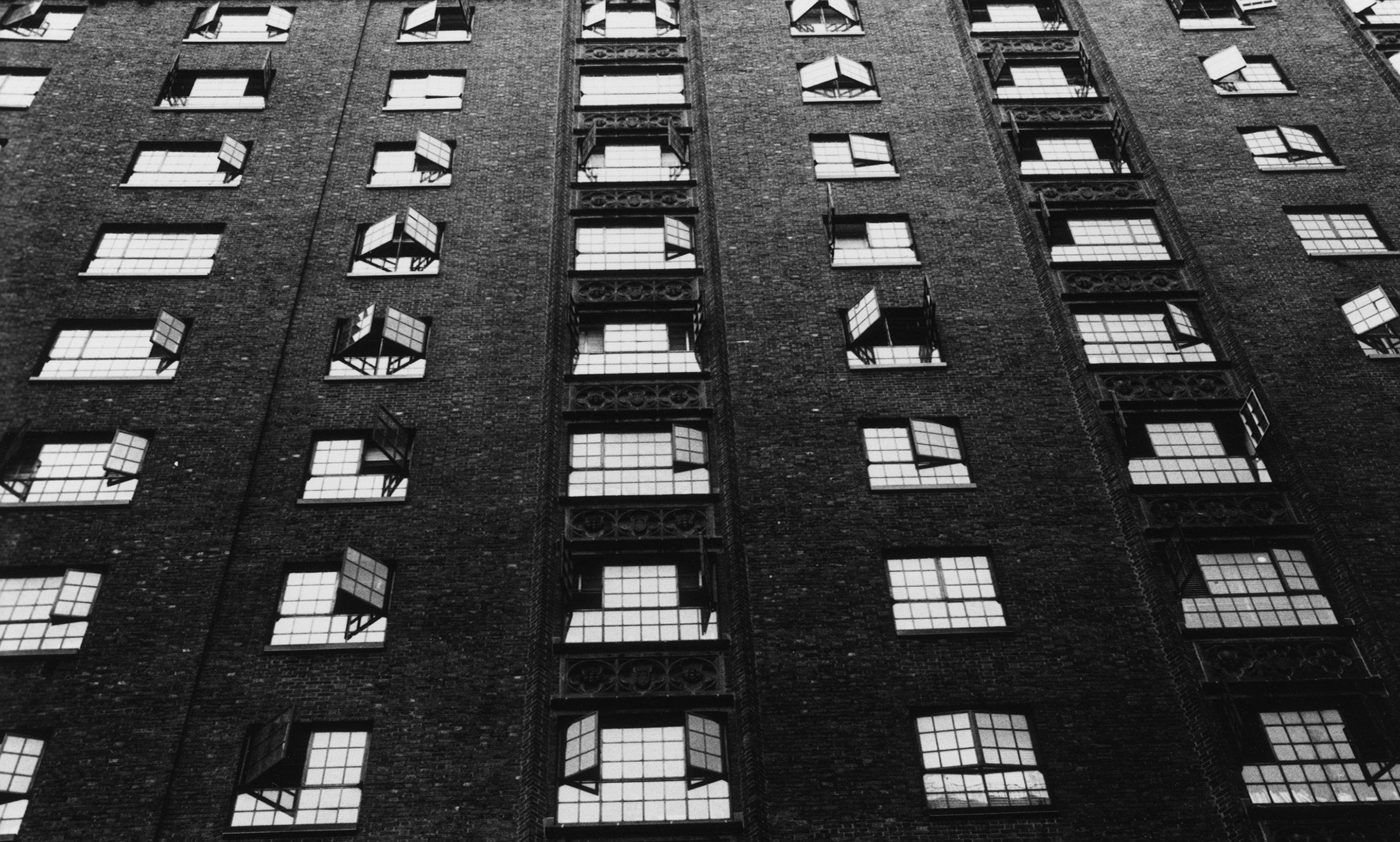

The sealed quiet of the hallway, where my mother’s muffled voice was the only sound, opened into the expansive din of the city at night. You forget how big Manhattan is until you get on a roof. On the ground everything is dense and obscured, but now I had a wide view of dark Central Park and beyond that the Plaza and the low skyscrapers along Fifty-ninth Street and that building that had the columns that looked like lollipops and the big bright billboard for the History Channel that had been up all summer and way off above that the white and blue lights of the Empire State Building and the sky, clear and purple and starless.

I lay down at the south edge and rested my elbows on the little ledge there and looked down at the roofs and hoods of parked cars. Somebody cleared his throat behind my back, pretty much scaring the shit out of me. If I’d been standing, I probably would have fallen off.

“Hello, Miss Eva.”

I rolled over and sat up. Zelensky was sitting in a lawn chair at the other end of the roof, barely more than a silhouette in a fedora. The dim orange point of his clove cigarette went up to his mouth, flared, went down again.

I laughed.

“I didn’t mean to scare you,” he said.

“You look like the killer in a bad detective movie. Dun-dun-DUNNN.”

He had a bottle in his lap, one of those small bottles of whiskey you see homeless people with sometimes. I got up and wiped the roof grit off my paisley shorts.

“Sit, sit, please,” he said, getting up. But I didn’t want to sit and have him stand, so we both stood there, just out of reach of each other. He wore a beige trench coat over a light sweater, and I didn’t understand how he wasn’t sweating to death in the heat. The clove cigarette almost hid the other smells of him.

“I’ve never been up here,” I said.

“It’s not so bad. I sleep over there sometimes.”

He pointed to a blanket and pillow lying near the northwest corner. There was a low wall separating this roof from the one to the west and no wall at all along the north edge, which dropped into the alley behind the buildings.

“It’s nice to sleep outside,” he went on. “The rooms in this building are too small, like elevators. I don’t like small spaces.”

“Maybe you should move out of the city,” I said.

“I don’t much care for open spaces either, unfortunately.”

I could see his face clearly now that I was close. He suddenly looked concerned, like he’d forgotten his manners, and he held up his cigarette.

“Would you like one?”

I had tried smoking once, the previous fall, desperately wanting to like it, but I’d hated it.

“Sure,” I said.

I took one from him and leaned in so he could cup a shaky, liver-spotted hand around the end and light it for me. I coughed for about thirty seconds, and he laughed the whole time, and we stood there like that, coughing and laughing, me trying to tell him between coughs to stop laughing but never getting the words out.

“Real funny,” I said.

“I thought all girls your age smoked.”

“It’s bad for you,” I said, surprising myself with how coy I sounded.

He shrugged. “Everything is bad for you.”

We stood looking at the illuminated city, the white windows stacked high in the dark.

“I was thinking the other day about your father,” he said. “Is it still sad for you?”

Somehow this didn’t surprise me. Somehow it felt like a totally appropriate question to ask, like we’d established something: definitely not a friendship, but an acquaintance where the normal boundaries and protocols didn’t apply.

“I don’t really remember him. He traveled a lot. He was tall, or tall to me, anyway, and he had a beard. I didn’t like kissing him because of that.”

Out of the corner of my eye I saw Zelensky chew his lower lip. “For me too. I don’t remember much of my parents. We were very poor. We lived in a basement. My mother used to cook our dinners in a coffee tin. She was always singing, I remember that. I don’t remember what songs. My father was a plumber, and she was nothing, a Gypsy woman. The boys used to throw rocks at me for that. And then they were both gone, when I was still very young. It was just me and my sister for a long time. And these women who took care of us. I could never sleep when she wasn’t around. My sister, I’m talking about. I was older, so this was a little,” he made a vague wave with his hand, “embarrassing to me. You remind me of her.”

“Me?”

“You’re the same kind of brave, maybe.”

I didn’t know the right response to something like that, so I asked, “Where is she now?”

“Dead. Everyone is dead. La-di-da-di-da.”

“Real cheery.”

“I have never liked that there are no stars here.”

“There’s one or two. You can see the moon, at least.”

“The nuns used to say all the stars were angels.”

“You knew nuns in Brooklyn?” I asked.

“Not in Brooklyn.” He took a drink, the whiskey making splashing sounds in the glass bottle. “You understand, I never believed this kind of thing, but when you are that age, it doesn’t matter whether you believe in something. It can be real when you’re bored and false when you’re tired of it. For my sister, though, this lack of stars was very upsetting: all the angels gone.”

“So how did you end up in a freak show?”

“You could see the shows then for a quarter. I sat through one and went up to the man afterward and told him, ‘I can do that. My mother was a Gypsy. It’s in my blood.’ He gave me this little fire on a stick, and I put it in my mouth.”

“But how did you know how to do it?”

He laughed. “I didn’t. I almost burned off my tongue. For years I could taste nothing. Truly. But this man who ran the show, he decided if I was crazy enough to do that, he could teach me to do anything. That’s how I supported us for a while, me and my sister, until she got married and moved away. Of course now I’m too old to do much at all.”

“You can fix sinks,” I said.

“Like my father. Maybe it is impossible not to take after our parents, even for orphans.”

“Those old movies I watch all the time were his,” I said. “My father’s, I mean. I watch these black-and-white people in their black-and-white stories and think, Maybe my father laughed at this. Maybe my father agreed Fred MacMurray was underrated. But I guess I’m not technically an orphan.”

“Everyone’s an orphan if they live long enough,” Zelensky said, and apparently he found this hilarious, because he began laughing so hard his eyes watered, and I could hear this phlegmy rumble in his chest. He started coughing.

“You OK?” I said.

He nodded, still smiling, trying to catch his breath. He wiped his eyes with the back of his hand, and it surprised me again how his eyes looked so much younger than the rest of him.

That night I lay in bed thinking of Zelensky up there, sleeping right above me. I wondered if he slept on his back so he could see the sky, or on his stomach, or curled up on his side. It was almost impossible to imagine him asleep. I dreamed he was young again. I was his sister, and I was at a huge circus watching him alone in the ring, extinguishing torches in his mouth, swallowing swords. Something happened to make the crowd turn on him, and I had to borrow a pair of wings from the woman next to me and swoop down to save him. He was whistling as we flew, and I woke to the sound of him whistling his way down the stairs for his morning walk in Central Park. It had never occurred to me before why I heard his whistling and footsteps so clearly: he came from the roof and passed right by my door. The slam that always woke me was not his apartment door below us but the trapdoor down the hall. I thought about what he’d said that day he came to fix the sink, about how we were all each other’s angels, and if he really believed that, even a little, then what kind of paltry, selfish angels were we talking about?

A couple of weeks later I was in the basement of Annie Cheapskate’s thrift shop at Bleecker and Broadway, looking for a faux-sable coat, when the whole place went dark. I mean completely dark, no light at all. I couldn’t see the fur in my hands. No one made a sound. And of course I thought: Terrorist attack! Then someone, probably thinking the same thing, said, “Is this the afterlife?” and everyone let their breath out and laughed nervously, and a woman with a flashlight steered us all toward the stairs. I wished I had been the one clever enough — brave enough — to say that.

Out on Broadway, traffic was jammed. The stoplights were out, and everyone was honking and trying to figure out whose turn it was to go. People huddled around parked cars to listen to the radio news: the whole city was blacked out, maybe the whole state. All these strangers, these adults with jobs and responsibilities, stood around talking and joking together, taking the edge off their alarm. A white woman in a pantsuit was talking to a Hispanic janitor, and he was showing her with his hands how the city’s power grid is laid out. A homeless man with grimy bare feet stood in the middle of the intersection directing traffic. The drivers did whatever he waved at them to do.

I could have swung by my old neighborhood and looked for familiar faces, but instead I started walking uptown slowly, telling myself to take it all in, because this was something people might talk about one day. The subways weren’t running, and there weren’t any empty cabs. The sidewalks were like one big party. Bars sold beer cheap, with no way to keep it cold, and people stood outside drinking and laughing. Places offered giant ice-cream cones for a dollar. Nobody was going back to work. There were sirens coming and going in the distance. I got updates from car radios as I passed: No power until tomorrow. Entire Eastern Seaboard out. Probably not a terrorist attack.

I stopped at Twenty-first Street to get a slice and some water. My mother was always telling me that pizza was exactly what I shouldn’t eat: “You get fat now, you’ll be fat all your life. That’s the one thing a man won’t forgive or overlook.” I pretended I had an itch and reached under my arm and around to where my bra strap cut into my skin: a soft swell of flesh bracketed the strap line. I used to laugh at women with back fat. Even the words sounded funny together: back fat. Now I had back fat, or was close to having back fat. I ate the pizza faster.

By the time I reached Times Square, the sun had set. Half the sky was red, the other half a darkening violet, and the first stars were already glimmering overhead. Times Square was dark: no flashing signs or advertisements, no electronic news ticker. Enormous underwear models brooded over the crowd. The silhouettes of buildings looked like sharp geometric shapes cut out from a construction-paper sky. People took pictures, flashes going off in the dark. They stood around looking up at all the lights that did not come on, like nothing had ever been stranger. I was standing in Times Square looking up at stars, bright and close.

I almost walked right into a man at Fifty-ninth Street. We both apologized, alarmed at how invisible we were.

In my neighborhood people had flashlights and glow sticks. Radios everywhere murmured the latest news. People sat on stoops and in lawn chairs on street corners. One man was talking about the last big blackout, in ’77, eleven years before I was born: “People broke everything that time. People burned and looted, and we all just locked up and waited for the lights to come back on.”

On the sidewalk in front of my building there was a big group of people standing along the curb and leaning on parked cars. There were candles everywhere, and it occurred to me that light was really just a fragile space hollowed out from darkness.

At the center of all these people, someone was playing guitar. Calvin, I thought, but it wasn’t Calvin. It was some guy I’d never seen before wearing a shark-tooth necklace and a Hawaiian shirt, handsome in an aging-surfer kind of way, playing that god-awful, shoot-me-in-the-head “American Pie.” Of course everyone was singing along. The Duck was there, and the landlady, and all these neighbors I never knew existed, and it should have been, I don’t know, nice, or touching. I should have thought: Wow, this is some serious bonhomie. But all I could think was how it would never ever be OK to sing along to “American Pie.”

I didn’t see my mother in the crowd, but I found Calvin, well away from the Duck, leaning against one of the trees that my mother insisted were elms despite knowing nothing about trees. He was drinking red wine from a clear plastic cup.

“Where’s your guitar?” I said.

“I can’t ham it up like this guy. He plays over in the park sometimes for money. He’s got CDs he sells under the name ‘Central Park Guitar Guy.’ ”

“You think the Duck’s going to take him upstairs?” I asked.

“Did you find your mother?” he said. “She was looking for you.”

“Where’d she go?”

He shrugged.

“Do you have any more wine?” I said.

We went up to Calvin’s apartment, him leading the way with his flashlight. I held his cup for him while he opened the door. He had trouble with the lock again, just like the morning after he’d left the Duck’s. My apartment was closed up and quiet, but then, why would my mother be in there, alone in the dark?

“I was in Grand Central,” he said. “It went dark, and a few people screamed. Then the emergency lights came on, and everyone was just standing there with these terrified faces.”

Finally he got the door open, and the flashlight’s weak, spider-web circle swept over the walls, all of which were incredibly close. It was less a room than a short hallway dead-ending in a window. There was an unmade mattress on the floor and a desk beneath the window and a packed bookshelf surrounded by stacks of books. Just to the right of the door newspapers were piled two feet high.

“I keep meaning to take those out,” he said. He walked across the room much quicker than I could, not kicking or tripping over anything. The bottle of wine was on the desk, and when he put the flashlight down to pour me a cup, I couldn’t see anything except the circle of white light reflected in the black window.

“You want to go up to the roof?” he asked.

“No,” I said, shutting the door.

We sat on his mattress with our backs against the wall. My heels hung over the edge, not touching the floor. He turned off the flashlight, and we were quiet for a minute, breathing in the dark, listening to that fiasco of a singalong outside. They were singing “Yesterday” now. His sheets smelled like they hadn’t been washed since the last time something had happened on them, and I wondered if the Duck had ever been naked with him here on this mattress, or if he always went to her apartment. There was a little slurp every time Calvin sipped his wine.

“Seen any good movies lately?” he asked, which just made me mad, because it was such an insipid question. I pictured him tutoring his SAT students, girls about my age, asking them stupid questions like that just to be polite, then tuning out their answers.

“How do you think the first kiss happened?” I said. “Like the very first one — and don’t say sex, because it’s not like anyone had to kiss to make babies.”

“Well —”

“I have this theory,” I said, shifting so that I was kneeling now, turned toward him in the dark. “I think two people were talking, or grunting in cave-man speak, or whatever, and one of them finally got to this point where there were no more cave-man words to express what he wanted to say. And so this cave-man guy took his tongue and lips, his little word instruments, and just pushed them into her word instruments.”

“ ‘Word instruments’?” he said.

“I like to think it was like that. What else do you do when there are no words? And those would have been the first two people to feel a little bit of what it was like to fall in love. There had to be two people who were the first to fall in love, before the idea existed for anyone else. Don’t you think?”

“It never really occurred to me.”

“Have you ever been in love?”

“I don’t know. I guess.”

Someone came up the stairs, creaking, and then keys were jingling at my end of the hall. That would be my mother. I heard the door open and close and waited for her to call my name, but she didn’t.

“You should go tell her you’re OK,” Calvin said, half whispering.

I touched his face. I meant to touch his cheek but almost poked him in the eye. He didn’t say anything. I traced my fingers very slowly over his forehead, his eyebrows.

“Eva . . .”

“Shhh.”

I felt his closed eyes with their long lashes, his long nose, the stubble of his cheek. I rested two fingers on his dry lips, my heart beating so hard he probably felt it through my fingertips. This is what it feels like when anything can happen next, I thought. His lips opened slightly, and I couldn’t tell if he was getting ready to speak or if he had started to kiss my fingers, then lost his nerve.

He took my hand in both of his and placed it gently on my lap.

“Stop,” he said.

Our faces were close in the dark. I pulled away from him.

“What did you think was going to happen?” I said. “I wasn’t going to do anything.”

I got to my feet, and he didn’t say anything or try to stop me. You thought about it too, I wanted to say. You brought me up here just to see what I would do and how far you would go. But I knew what he would say, about my age, about all sorts of things.

“Thanks for the wine,” I said. “Can I borrow your flashlight? We don’t have one.”

He handed it to me, and I waited, but all he said was “Good night, Eva.”

In my apartment I shut the door and leaned back against it. I’d thought I’d find my mother in there with candles, but the place was dark. I ran the light all over the living room. Her bedroom door was closed, but mine was open. I heard sniffling in there, and I pictured her sitting on my bed, distraught over my whereabouts, clutching my stuffed bear. Now there would be some scene, and the problem was I wouldn’t care. She would be a wreck, and her shouts and sobs would be so much noise to me, and my thoughts would instantly go to Calvin or that sequel to The Graduate I kept wishing someone had made.

I poked my head into my room and shined the flashlight over the empty bed and down onto the floor, where Zelensky was kneeling beside my hamper. He had two big handfuls of my pink panties pressed to his face. When the light hit him, he let out a muffled howl and turned away, bending his head low. But for a moment before that, I saw his eyes, wide and red, his face wet with tears, and it was like he didn’t even see me, like he was in a different place seeing something else entirely.

“What?” I said, not to him but to the fact that this was really happening. “What?”

He hunched into a tight little ball, pounding the hardwood floor with his fist. He sounded like something wounded and dying. My clothes were all over the floor around him, my shirts and shorts and bras and panties — my dirty panties, from the hamper. He knew how I smelled.

I ran to my mother’s room. She wasn’t there. Nobody was. I locked the door and stood waiting. I could still hear everybody singing together outside.

“Miss Eva?”

He was right on the other side of the door. His small, broken voice.

“Miss Eva.”

I thought about opening the door. Just for a second. It was like there was this other me hovering over the real me, taking in the situation objectively and finding that maybe, in the grand mess of the universe, this wasn’t such a big deal, this wasn’t going to kill me, this wasn’t something I had to hide from. People did weird, even hurtful, things, but it wasn’t the end of the world.

This other me came and went, and then there was just the real me, in the dark with a locked door between me and a lunatic who had broken in to sniff my dirty underwear.

The front door opened and closed, and I heard him slink off down the stairs. I didn’t unlock my mother’s bedroom door, though it did occur to me that if he had the key to the apartment, there was no reason to think he didn’t have the key to this lock, too. If he’d wanted to come into my mother’s bedroom, he probably could have. But he hadn’t. He had wanted me to come out.

I got under the covers of my mother’s bed. It was so hot I was sweating. There were no air conditioners running, no sound of traffic or TVs through the walls, just those voices outside like ghosts celebrating something a hundred years distant. I will never sleep again, I thought, but I must have, because suddenly I jerked awake to the sound of my mother knocking on the door. It was still dark; people were still singing.

“Eva? Are you in there?”

When I opened the door, she felt for me in the dark and grabbed me by the arms and shook me.

“Where were you? Where did you go? I was calling your cell.”

“The connections are all screwy.”

“I went everywhere. The park, that old cafe you like on Seventy-first, everywhere.”

I think she wanted me to apologize and break down in her arms. I let her shake me and shout at me a little longer until she was the one who apologized and broke down.

“I didn’t know what to do,” she said. “What would I have done? Tell me. What would I have done?”

I stood there holding her. We were pretty bad at holding each other. I never hugged her tight, just kind of draped my arms lightly around her. You would think she would have been better at it, that she would have had some kind of automatic mother skill for holding her daughter, but she kept shifting, first pinning one of my arms against my side, then stepping on my foot, then squeezing too hard.

“Did you see that handsome man outside with the guitar?” she said.

I slept well into daylight the next morning, in my own bed. When I woke up, my alarm clock was blinking, and the TV was on in the other room. I thought I could smell Zelensky’s clove-and-old-shoe-and-aftershave smell, but a moment later I couldn’t, and I thought it might have just been in my head. It felt like about two weeks had passed.

My mother was on the couch watching the news, both hands holding her TAME THIS SHREW mug.

“The power’s back,” she said.

“What was it?”

“Oh, some power station upstate. It hit everybody down to Baltimore, if you can believe that. It hit people in Canada. Now they’re going on about the broken infrastructure of the country. I still wonder how they know a terrorist didn’t cause the accident.”

In New York five people had died: two from carbon monoxide, two in a fire, and this one man who’d died while trying to break into a shoe store.

The next day I came back from a Billy Wilder retrospective at the theater on West Houston and found my mother standing on the stoop, talking to the landlady, making theatrical faces of shock and grief.

“Oh, Eva, it’s so sad. Mr. Zelensky’s dead.”

I stopped at the bottom of the stoop and waited for her to say more, which of course she would, since every story, once she heard it, became her story.

“He fell off the roof. They’re not sure how it happened, but they think maybe he was up there during the blackout and slipped.”

“He slept up there sometimes, in the summers,” the landlady said. “I found his body out back in the alley this morning.” Her eyes were red. She was almost forty, and it occurred to me that when Zelensky had first moved in, she would have been about my age.

“They think maybe he was drunk,” my mother said. “That poor, lonely man drinking all alone on the roof. I remember how nice he was when he came to fix our sink. And always such a gentleman, taking off his hat whenever he passed me in the halls. Remember that, Eva? Remember when he fixed our sink?”

There was a memorial service at a Catholic church a few blocks down, right across the street from the park. It made perfect sense for me to go, but I hated showing up anywhere with my mother. I was embarrassed to be seen with her and equally embarrassed that I wasn’t mature enough to get over the initial embarrassment. As we walked down Central Park West, she fussed constantly with her best silk scarf and subjected me to memories of her father’s funeral.

“You were too young to know him, of course, but your grandfather was maybe the most dashing man in Hudson County. They don’t use that word anymore, dashing. All the girls loved him, even the young ones, even my friends from school.”

“Did Dad like him?” I asked. I already knew the answer. She’d told me these stories before.

“I wouldn’t say they liked each other. I’m sure they would have gotten along if I hadn’t been around. Men are strange that way. They can’t tolerate being anything less than the center of a woman’s world. It doesn’t matter if it’s a wife, a daughter, a pretty waitress, whoever.”

I had been to exactly one funeral, my father’s, and all I remembered was a crowd of heads in pews and a lot of organ music. There weren’t that many people at Zelensky’s service, though almost everyone from our apartment building was there. The landlady said how wonderful it had been to have him as a tenant and how helpful he had always been. She ended by making the sign of the cross and blowing a kiss up to the vaulted ceiling.

A cheerful blond woman named Polly, chubby and middle-aged, introduced herself as his niece. She was here from New Jersey, and she talked about how he used to come to her birthday party every year in a borrowed tuxedo and put on a magic show for all the kids: rabbits pulled out of hats, doves bursting from coat pockets. Every Halloween he would bring over a pumpkin, and they would carve a jack-o’-lantern together. They would try out funny and scary faces on each other, to figure out how they wanted it to look, and he’d let her hold the knife while they carved, his hand guiding hers. He made it his mission to get a bigger and bigger pumpkin every year until one Halloween, when she was seventeen, he showed up with this enormous pumpkin under his arm and took one look at her in her dress and said, sadly, “You’re too big for pumpkins.”

He had never been religious, she said, but he’d wanted to be buried in the Catholic tradition, in honor of the people who had helped him during the war.

There was a little reception in the community center in the basement of the church. It was one of those blandly depressing rooms, walls of blue and white concrete covered with truly horrible crayon drawings some kids had done of their families, in which every mother was a broom-haired scarecrow and the children were all grinning, deformed lumps. There was a kitchenette against one wall and folding chairs set up around tables with not too many people sitting at them and another table with doughnuts and coffee in a cardboard box with a spigot. I got some coffee and a Boston cream and wandered over to where my mother and the Duck were talking to the niece.

“Eva, I was just telling Polly here how nice Mr. Zelensky was when he came to fix our sink.”

“He was real nice about the sink,” I said.

“He liked helping people,” Polly said. “It was just his way.”

“It’s a dying breed,” my mother said, instantly mortifying herself. “I mean — God. Excuse me. Where did you get that coffee?” she asked me.

After my mother had gone, the Duck kept quiet, and Polly went on smiling at me the way older women do sometimes, like they’re inviting me to say something even though I’ve got nothing to say.

“He was an interesting guy,” I said.

“He had a crazy life. I feel like even I never got to hear the half of it.”

I think it was only to annoy the Duck that I asked Polly, “Was he really in a concentration camp?”

Sure enough, the Duck gave me a disbelieving stare, shaking her head slowly, but Polly seemed unfazed.

“For a little while. Toward the very end of the war. He and my mother spent most of the war in a convent near Brest.”

“He lived in a convent?”

“The nuns hid him from the Nazis. He was just a boy then, younger than you. My mother they could dress up like a lay sister, but they had to hide Uncle Janek. He used to tell us these stories,” she said, laughing and putting a hand to her chest, “about how they kept moving him to different hiding places. They hid him in a well. They hid him in a cupboard. Once they hid him for something like four months in the laundry room. They just buried him in these huge bins of dirty laundry. Which sounds funny, but the soldiers never checked there. He used to joke that nothing scared Nazis like a nun’s underwear. They got him eventually, of course, but by then the war was almost over. He got lucky.”

I chewed my doughnut. There was a little bit of custard at the corner of my mouth, but I didn’t wipe it yet.

“I actually tried calling him during the blackout,” she said. “I know how much he hated the dark. Did you talk to him often?”

“No. Not hardly at all, really.”

“We kind of fell out of touch after my mother died. But that’s how everything goes, I guess. People slip away.”

“Everyone’s an orphan if they live long enough,” I said.

She cocked her head, smiling, waiting for me to explain. But I couldn’t have explained it, not to her, not even to myself.

Outside, the sun was blinding. I sat alone on the church steps. Across the street, joggers veered in and out of the park, dogs strained at leashes, tourists haggled over portraits of John Lennon, and couples bought hot dogs from the brown-skinned vendor. I thought about what all this must have looked like to Zelensky, after his childhood of hiding and Nazis and all those things that were as real to him then as Central Park was to me now. Then the light changed, and a blur of taxi yellow and sun-spangled glass hurtled between me and all of it.

And what was I supposed to do? What could I have done that would have made any difference?

I wiped my eyes. My back was sweating, and there was an itch I couldn’t quite reach where my bra cut into my skin. It was one of those late-summer days where nothing was in any rush to happen, and I could have sat there all morning just watching the squirrels chase each other up and down the trees.