We use cookies to improve our services and remember your choices for future visits. For more information see our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

Then & Now

Feeling connected, struggling to adapt, restoring peace through justice

In this new online feature inspired by the recently retired “One Nation, Indivisible” section of the magazine, we’ll dive into our archives to link our past to our present. We hope these pieces spark conversation, contemplation, and self-reflection.

In her essay in this month’s issue, S.B. Rowe comes to a deeper understanding of what it means to love a family member who has an addiction. This excerpt from an interview with Maia Szalavitz by Arnie Cooper in our June 2017 issue explains the importance of social connections in addiction recovery.

Compassion is important. People need to feel connected and wanted in order to be at their healthiest. That’s true whether you have an addiction or depression or schizophrenia or cancer. . . . The best way to relieve stress is not yoga or meditation — although those can be wonderful — but human contact. We need each other.

We asked our readers to tell us stories about “Mail,” and many wrote about how their lives were changed by what they received in their mailboxes. Their words reminded us of this Readers Write entry on “The Internet” from August 2012. Which do you prefer, e-mail or postal mail?

I was twenty-seven and riding my bicycle coast to coast across the United States. Along the way I was trying to live simply and “make the journey the destination.”

I’d taken a three-day break at a hostel in Missoula, Montana, when I met Dan, who pulled in on a beautiful light-green Bianchi, not a scratch on it. He was riding cross-country as well. Our personalities clicked, and we decided to ride together, despite the fact that we had different approaches to travel: I’d brought a cheap tent, a couple of pairs of riding shorts, a change of clothes, and little else. Dan had bright spandex outfits, shades with interchangeable lenses for varying degrees of sunlight, and a specially engineered rack to tow all of his belongings. He also had a cellular phone — an expensive rarity in 1997. For fun we used it to order pizza from a campground.

After a few weeks of riding, we pulled into Iowa City. Dan said he needed to check his “electronic mail.” I followed him into the University of Iowa computer lab, and he explained how he’d set up a mail account on the Internet and could now send and receive messages from any online computer. I could do it too. For free.

I was skeptical.

“Don’t live in the Dark Ages!” Dan joked.

I followed his instructions to get my own account, then prepared to send a test message to his address. Dan showed me where to type the subject and the body of the message, then leaned over my shoulder. “OK, now watch this,” he said, fingers poised to click SEND. “This is going to change your life.

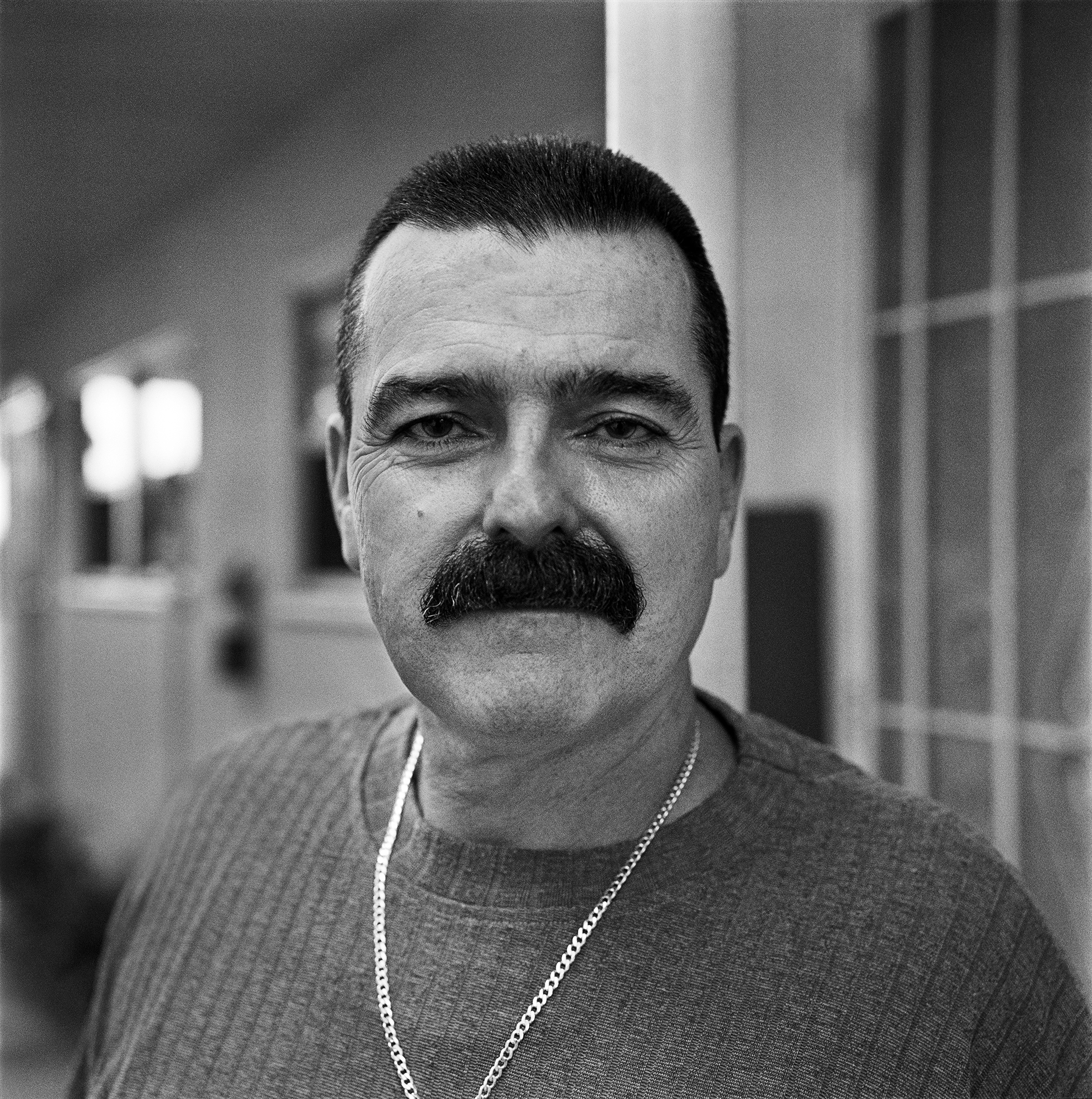

After serving eighteen years in prison, Saint James Harris Wood says he feels like a time traveler when he uses technology. His essay, “I Still Don’t Feel Free,” in this month’s issue brought to mind this photo series by Joseph Rodríguez in our July 2017 issue, which shows other ways people have struggled to adapt to life outside of prison.

“What scares me the most is not making it.” Joey had served twenty-seven years in prison and now worked for the nonprofit Restorative Justice. He’d been at Walden House for six years and was still learning to assimilate and adjust to modern technology.

Ira Sukrungruang’s essay about parenting in our March 2021 issue reminded us of this poem by Duncan Moran. What has being a parent taught you?

Where There Is No Other

At ten months my daughter turns the TV on, the volume up loud. She is not the same as when she was pulled purple from the womb. At first the changes were small, she’d grasp fingers, make a fist. Now she’s up before I notice, off across the floor. Playing with her, I see in the mirror a man. He is not the man I uncover when shaving. He is younger, not much older than a child. Each day when we play I see him and each day he looks a little younger; in a few years he’ll be no older than my daughter. Yet, he won’t be the boy I was, frightened by the dark, by the racket crickets make. He’ll be different, he has her to play with. As she grows I grow less afraid. In a year or fifty, when I die, he’ll be reentering the womb: we’ll slide into darkness together. By then, my daughter, if she’s lucky, will have discovered that other child in her. Then they too, will meet in darkness where there is no other.

In Feliz Moreno’s March 2021 interview, law professor Lara Bazelon explains the deep-rooted flaws in our justice system and what can be done to begin to correct them. One process she discusses is restorative justice, a topic we have covered before, as in this excerpt from D. Killian’s February 2003 interview with Marshall Rosenberg.

Restorative justice is based on the question: How do we restore peace? In other words, how do we restore a state in which people care about one another’s well-being? Research indicates that perpetrators who go through restorative justice are less likely to repeat the behaviors that led to their incarceration. And it’s far more healing for the victim to have peace restored than simply to see the other person punished.

We’ll mail you a free copy of this month’s issue. Plus you’ll get full online access—including more than 50 years of archives.

Request a Free Issue