In 2011 conservationist and author John Davis hiked, cycled, and paddled some 7,600 miles, from Florida’s Everglades to Quebec’s Gaspé Peninsula, without ever setting eyes on a wolf or cougar in the wild. This would have been impossible a few centuries ago, prior to the arrival of Europeans in North America, when large carnivores roamed widely, unimpeded by sprawling cities, busy roads, aggressive logging and mining operations, and millions of domineering humans. One goal of Davis’s ten-month adventure was to draw attention to the almost total extirpation of top predators from their historic ranges east of the Mississippi River, a biological impoverishment that passes as normal. Davis is a relentlessly hopeful person, though, and his primary objective was to explore opportunities for welcoming the missing animals back to the habitat that belonged to them long before it belonged to us.

How might that be accomplished? By linking together the remaining undeveloped land—national parks and wilderness areas, along with public and private holdings—to create a vast system of ecological reserves. Called “rewilding,” this continent-spanning approach to conservation was initially articulated by Dave Foreman, cofounder of Earth First!, a radical environmental group. As a young man Davis was inspired by the group’s slogan, “No compromise in defense of Mother Earth,” and began volunteering his time. In the early 1990s he and Foreman, in collaboration with leading environmental scientists and conservation activists, started a new organization devoted specifically to rewilding: The Wildlands Project (later Network). Davis edited the organization’s journal, Wild Earth, for five years, then oversaw the grant program of the Foundation for Deep Ecology for another five. Currently he serves as the Adirondack Council’s rewilding advocate and the Rewilding Institute’s executive director. Regardless of his job title, a belief in the intrinsic value of wild places and wild creatures motivates all his work.

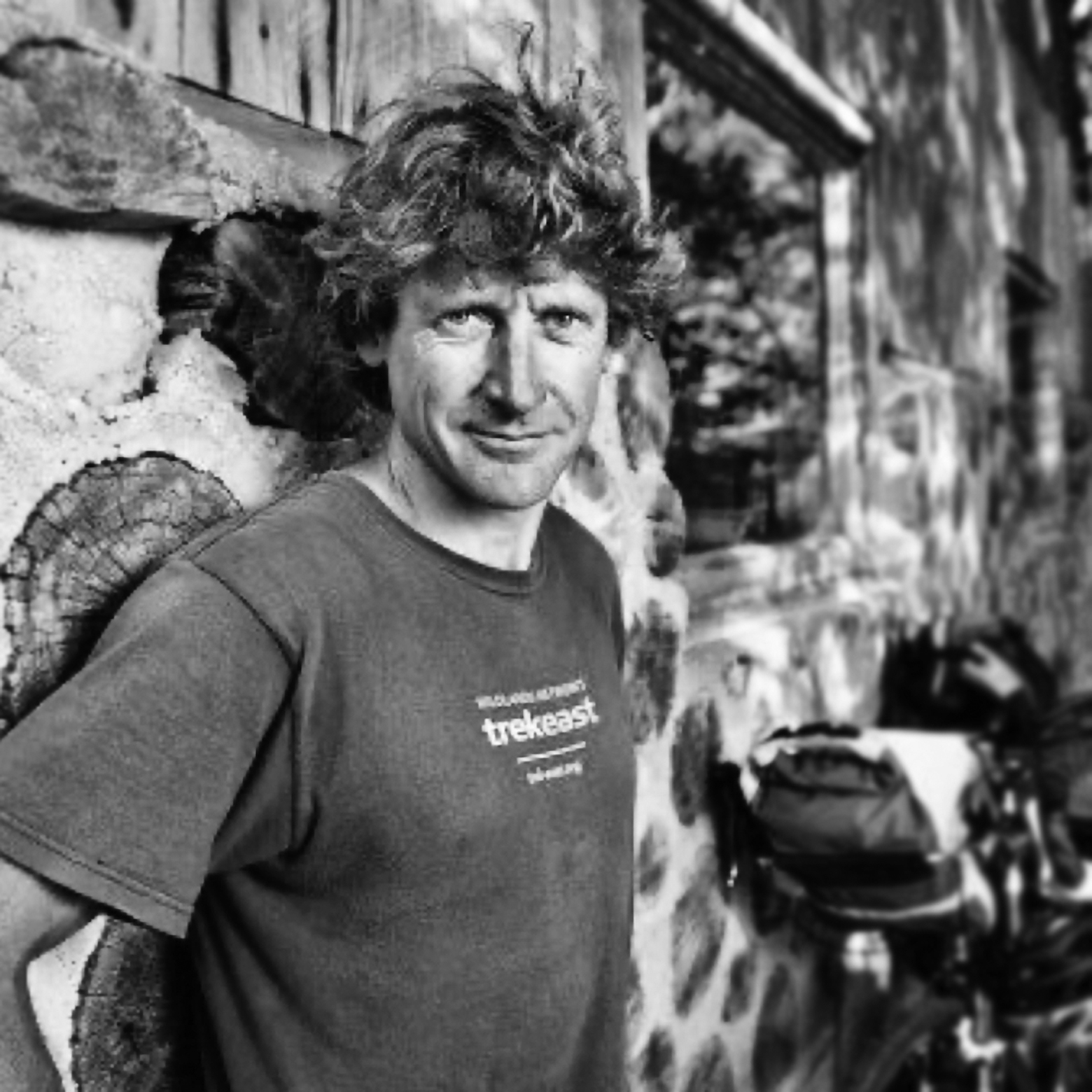

Davis has been described as a combination of a naturalist and a triathlete. Indeed, he’s the type of conservationist who trades his desk for the field whenever the chance arises. Following the 2011 trip that became the subject of his first book, Big, Wild, and Connected: Scouting an Eastern Wildway from the Everglades to Quebec, he undertook a similar expedition along the Rocky Mountains. A documentary film, Born to Rewild, shadows Davis as he travels five thousand miles from Sonora, Mexico, to British Columbia, Canada, searching for animals, mapping their routes, and stopping often to talk with activists, ranchers, biologists, and state transportation officials. Closer to home, in the Adirondack Mountains of New York, Davis rambles the hills of his local watershed and promotes the protection of a wildlife corridor between Split Rock Mountain, on the western shore of Lake Champlain, and the designated wildernesses of the High Peaks. His second book, Split Rock Wildway: Scouting the Adirondack Park’s Most Diverse Wildlife Corridor, presents a vision of rewilding at the regional level.

I was raised in Vermont, directly across Lake Champlain from the small town of Westport, where Davis resides in a one-room cabin that has no electricity or plumbing and is accessed via a narrow footpath through the woods. We met there in August 2024 and spoke for three hours on a deck overlooking a beaver pond, the red and green lights of my digital recorder glowing strangely against the backdrop of water, leaves, and gray sky. Davis was eager and affable in conversation, hardly a misanthropic hermit. After sitting down, he pointed to a hornet’s nest and informed me that the deck was a shared space. “I’ve made an agreement with them,” he said. “They are not to sting.” The hornets did sting, however, and Davis cursed, but I detected no anger in his voice, only bafflement. It was likely my presence that prompted the shift in the hornets’ behavior.

[Not all conversations are as linear and succinct as they appear. This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.—Ed.]

John Davis

Tonino: What exactly do you mean by rewilding?

Davis: I borrow the term from my late mentor, teacher, and friend Dave Foreman, who coined it about three decades ago. In short, it means wilderness recovery. In more detail, it entails protecting and restoring big, wild, connected spaces, and it puts special emphasis on bringing back the animals killed off and driven away by reckless human behaviors—especially the top carnivores, which are not just beautiful and charismatic but essential to ecological health. My old friend and colleague Tom Butler, who took over editing Wild Earth when I moved on to the Foundation for Deep Ecology, sums up rewilding as “helping nature heal.” I like to say that rewilding is giving the land back to wildlife and wildlife back to the land.

The need for big, wild, connected spaces was initially articulated by conservation biologists Reed Noss and Michael Soulé, who were close associates of Foreman. In 1998 they wrote a classic paper titled “Rewilding and Biodiversity: Complementary Goals for Continental Conservation.” Note the word continental. One of the hallmarks of rewilding is that it ups the scale from isolated ecological reserves to continent-spanning wildways. The full suite of native wildlife needs to be welcomed home to North America. In certain cases this may require active reintroduction, but fundamentally the goal is to assemble a network of wild landscapes that allows the animals to recolonize on their own and prosper naturally.

The Old English for an untamed creature is wildeor. It’s where we get our word wilderness, for self-willed land, or land of the self-willed animals. Rewilding is ultimately about protecting and restoring land for its own sake—letting the land express its will instead of constantly manipulating it, rearranging it, putting demands on it, taking from it, and damaging it. We might intervene with a light touch here and there, but as much as possible we let the land be.

Tonino: Where does rewilding fit into the story of North American conservation over the last century and a half?

Davis: In the nineteenth century naturalist John Muir and others focused largely on saving places of great natural beauty from the ravages of industrial society. But by the early twentieth century it was becoming clear that the aesthetically notable places, like some of our flagship national parks, weren’t necessarily home to the greatest ecological richness. Slowly but surely, wilderness began to be conserved not only for its gifts of solitude and spiritual inspiration but for its biological diversity.

The rewilding movement started with the realization that saving the remaining pieces of wild nature isn’t nearly enough. You cannot secure the natural heritage of North America with isolated, postage-stamp reserves.

Tonino: By the average person’s standard, those postage stamps are enormous. Yet conservation biologists have determined they are too small?

Davis: Exactly. Studies have shown that even ecological reserves of a million acres will over time lose species if they are isolated and surrounded by heavily used and abused lands—that is, if they are disconnected islands of habitat. An ecological rule of thumb is that a smaller habitat sustains less species diversity. Conservation biologist William Newmark did a study three decades ago that looked at mammals in various parks in North America, and he found that the rate of local extinction was inversely related to the size of the protected area: the larger reserves lost fewer species; the smaller reserves lost more. A viable reserve, one that enables populations to respond to environmental disturbances, requires millions of acres—and those millions of acres need to be connected to other, similar, reserves.

Rewilding owes much to the original conservation model that Reed Noss put into play in Florida in the 1980s. He proposed a network of cores and corridors. To start, the cores ought to be as big as possible and truly wild. The holy grail of cores is a national park that has also been designated by Congress as a wilderness area. Other cores might be national wildlife refuges, national monuments, or even private lands with a forever-wild conservation easement on them. Next, you buffer the cores with multiple-use lands. In the eastern United States these might be managed timberlands owned by corporations. Then you make connections between the cores: wildlife corridors that ideally have wilderness-level protection or something close to it.

Here we are on the porch of my cabin in Adirondack Park, which is a strange beast. It’s a state park established in 1892, but more than half of it is private inholdings. Of the total 6.1 million acres, about three million are fully protected from development and resource extraction by the state and land trusts, and more than half a million additional acres are under conservation easements that prevent development but allow logging. It’s the wild heart of the Northeast—vast and rugged, iconic in the history of conservation—but it’s still way too small. We lost our wolves and cougars long ago, and because we are an “island,” I don’t believe they will make it back on their own anytime soon. The nearest viable population of wolves is in Algonquin Provincial Park in southeastern Ontario. Along with many other conservationists around here, I work on the Algonquin-to-Adirondack connection, a vitally important wildlife corridor that is fragmented, especially along the Saint Lawrence River. We have to make these two parks continuous if we are ever again to see them as they were not all that long ago in the history of the continent.

Tonino: Picture a map of North America in front of us. Could you trace a finger along the major wildways that ought to be established?

Davis: In Rewilding North America: A Vision for Conservation in the 21st Century, Dave Foreman mapped the four highest-priority continental wildways. Three follow our major north-south mountain chains. The Eastern Wildway runs from the Florida Everglades through the Southeastern Coastal Plain and up the Appalachians to Canada. The Spine of the Continent Wildway runs up the Rocky Mountains from Mexico to Canada, taking in some of the surrounding deserts and grasslands that haven’t been too developed. The Pacific Crest and Coast Wildway runs from Baja up through California, Oregon, and Washington to British Columbia and southern Alaska, also taking in some low country. And then there’s the Boreal Wildway, which runs east-west across much of Alaska and Canada.

At the Rewilding Institute we want to add a Gulf Coast Wildway, which would run east-west across the Florida Panhandle toward Texas, just north of the Gulf of Mexico. It’s a badly fragmented region, but it’s not completely lost; a fair amount of natural habitat remains intact, including some grasslands of high ecological value. We also want to add a Great Plains Wildway, which would run north-south through the middle of the country. This could be doable because human populations in the shortgrass prairie have shrunk in recent years. Decades ago demographers Frank and Deborah Popper proposed a plan they called the Buffalo Commons: pay ranchers and farmers to take down their fences and retire their lands, establish native grasses, and reintroduce bison to the Great Plains, transitioning some ten to twenty million acres from large-scale agriculture to wild habitat. They argued that the drier portions of the Great Plains were being farmed in an unsustainable manner—hence the depopulation trend—and that their plan would be better economically in the long run.

The Wildlands Network has done a very impressive Eastern Wildway map, which zooms in and shows many of the regional connections that need to be secured. The map calls for the preservation of roughly half the eastern United States and southeastern Canada. Interestingly, eminent biologist E.O. Wilson came to the same conclusion with his concept of Half Earth: to stem the extinction crisis, we need to protect and restore at least half of the lands and waters on the planet.

Tonino: Where would we humans go if we returned half the continent to the wild creatures?

Davis: Well, much of Canada and the American West is already rather uninhabited by humans. In fact, I suspect more than half of the continent could become ecological reserves. I like the idea that, instead of wilderness islands within a matrix of human development, we reverse the pattern, and humans live densely clustered within a wild matrix. It’s not politically or economically feasible right now, but some such arrangement might be possible eventually.

It’s a huge subject, but I ought to briefly mention overpopulation, one of the fundamental problems in the world today and an awful obstacle to protecting and restoring nature. Eight billion people is just too many. In terms of human flourishing, it’s too many, and in terms of wildlife merely surviving, it’s an absolute nightmare. Studies by the World Wildlife Fund have shown that Earth has lost something like 73 percent of its wild animals in the fifty years between 1970 and 2020! We’re in the midst of a crisis of biological impoverishment, driven in large part by overpopulation.

Tonino: Ecologist John Terborgh once wrote: “That we should live in a world without megafauna is an extreme aberration. It is a condition that has not existed for the last 250 million years of evolutionary history.” Why the emphasis on carnivores in the rewilding movement? Why are they so important?

Davis: Many of them are keystone species, meaning their influence on the functioning and diversity of a given ecosystem is disproportionate to their numbers. Like a keystone atop an arch in architecture, these animals prevent collapse. When they are gone, you get cascading effects through the food web.

Here’s a classic example: In the eastern United States our forests are suffering from overbrowsing by white-tailed deer. Wildlife-management agencies want to limit deer populations to help the forests, but they don’t have the courage to suggest the obvious answer: restore the missing carnivores. Cougars and wolves will trim deer numbers—not eliminate them, just trim them—and, perhaps more important, they will regulate the deer’s behavior. Deer won’t congregate and eat all the northern white cedar because the carnivores know that deer like to eat northern white cedar and will be hunting in those spots. That’s a critical function of top carnivores: to keep herbivore numbers limited and keep them from overbrowsing sensitive plants.

Without top carnivores, you may also see an increase of mesopredators—midsize predators like raccoons, foxes, and opossums—and their proliferation will trigger yet more changes. A wolf won’t bother eating a songbird or its chicks, but a raccoon absolutely will, which means the forest’s avian population will be impacted. Maybe some of those birds the raccoon eats are primary-cavity nesters like woodpeckers, who excavate hollows in tree trunks. Secondary-cavity nesters like bluebirds and titmice and tree swallows depend on those hollows. As you can see, the cascade goes on and on.

So protecting wolves and cougars protects countless other smaller species of both animals and plants. If the rewilding movement has a single central image, for me it would be a wolf wandering from Mexico to Canada, or a cougar wandering from the Everglades to the Adirondacks and beyond. If we can make those long journeys possible for them, we will have simultaneously achieved many other conservation successes.

Tonino: Michael Soulé used to say that connectivity is more than a goal—it’s the natural state of things.

Davis: Indeed. I like to sum up why habitat connectivity is crucially important with four words: food, cover, sex, and change. Food: Many animals need to range widely to meet their dietary needs. A black bear might want to be near valley wetlands in spring but then switch to the high peaks during summer for cooler temperatures and late-season berries. Cover: Most animals that evolved in forests aren’t comfortable being exposed in fields or on roadways. They want the protection of the tree canopy and will be deterred from moving if there are too many large gaps. Sex: Animals need to be able to mix their genes. Isolated populations will suffer from inbreeding, so it’s important that individuals be able to travel to different areas to find mates. Change: In this unpredictable century of climate chaos, animals need to be able to follow their climate envelopes and find conditions that allow them to survive.

The Old English for an untamed creature is wildeor. It’s where we get our word wilderness, for self-willed land, or land of the self-willed animals. Rewilding is ultimately about protecting and restoring land for its own sake.

Tonino: You’ve written that “movement is as essential to life as air, water, soil, and food.”

Davis: Yes, wherever there is life, there is movement of one sort or another. Look at humans in affluent nations: We have cars and a sprawling road network that allow us to drive everywhere. I’m in my sixties and have owned a car for only about fifteen years of my life, total. For the most part, I’ve commuted to work on a bicycle, winter storms be damned. Traveling under my own muscle power has kept me in touch with the basic fact of mobility in the animal world.

Of course, the grim irony of our cars and roads is that, as they create connectivity and freedom of movement for us, they do the opposite for wildlife. The very means we employ to go places makes it much harder for many other species to go places. This issue is getting more and more attention, thank goodness. Road ecology has really matured as a discipline, and we now have federal and state agencies providing funding for wildlife crossings that allow animals to safely pass over and under dangerous roads. These infrastructure projects also benefit people: there are about two hundred fatal accidents a year in the US involving deer, elk, and moose, and many of them could be prevented if the ungulates weren’t forced onto our roads in the first place. How many deer, elk, and moose die because they’ve been hit by a vehicle is a whole other terrible story.

Tonino: What do you see as the primary forces of habitat fragmentation?

Davis: Roads are definitely the single biggest fracturing agent in this country. They divide habitat in unnatural ways. They change how animals move about. They cause roadkill. They erode banks and dump sediment into streams. They cause edge effects, like unnatural microclimates and increased risks of predation and parasitism and the introduction of exotic species. And that’s just the start. With roads you also inevitably get machines, noise, pollution, development, industry.

Farms and ranches also fragment habitat. Housing developments fragment habitat. The electrical grid fragments habitat, often needlessly. I get so irritated when I see utility companies clearing long avenues through intact forest to install power lines. Burying the lines along a road—an existing fragmentation zone—is more expensive at the outset, but in the long term it would be better for everybody. We’re experiencing more and more blackouts because the lines are up in the air instead of underground. It’s common sense.

Logging is also a major fragmentation agent. A lot of conservationists too readily embrace it as a potentially sustainable practice. Granted, as long as we’re using paper and lumber, we need some domestic logging. I am by no means in favor of protecting our home forests while exploiting forests in, say, South America. But the underlying problem is that we use far too much paper and lumber in the first place.

Tonino: You’re not a fan of the border wall separating the United States and Mexico.

Davis: The border wall is an ecological disaster. It purports to block the movement of humans, but really it only blocks wildlife. Among the charismatic species that ought to be traveling back and forth between nations but can’t are jaguars and ocelots. Historical records show that jaguars lived at least as far north as the Grand Canyon in Arizona, some four hundred miles from the border, and I think they ranged as far east as the Mississippi River too. There are currently no breeding populations in the Southwest. And if the wall is finished, there probably will never be another breeding population of jaguars in the US. The average determined person can circumvent the wall in a matter of minutes, but a jaguar, or an ocelot, or a Coues white-tailed deer, or a javelina—they don’t stand a chance.

And it’s not just the wall but the accompanying infrastructure. For most of its length there’s a parallel road that the Border Patrol drives, causing further noise and air pollution and disturbing sensitive wildlife and critical habitat. Some places along the wall are bright with artificial lighting, which harms butterflies and moths and bats and songbirds. We’ve created this whole military-industrial complex along the border, and towns there now depend on it for jobs. What I’d like to do is create jobs dismantling the wall and installing wildlife crossings on nearby interstates. I don’t know how to accomplish that economic transition, but I do know that taxpayers are spending billions of dollars to create an ecological disaster.

Tonino: You described farms and ranches as agents of fragmentation, but they do provide wildlife habitat, don’t they?

Davis: Like certain timberlands, well-managed farmlands and ranchlands can serve as effective buffer zones around the wild cores and corridors. But we need less of them on the whole. We need to grow food and raise livestock on fewer acres. Many years ago I helped start a group called the Wild Farm Alliance. It’s been working to foster wildlife-friendly farming techniques—teaching farmers how to coexist with carnivores. How can I keep coyotes or foxes from eating my chickens without shooting or trapping them? How can my farm serve as a piece in the larger puzzle of rewilding? Farmers who participate in sustaining our natural heritage should be able to charge a premium for their products.

As for ranching, it’s not a popular perspective, but one of the most important things we could do for wildlife throughout the West would be to phase out livestock grazing on public lands. This would entail providing generous compensation packages for ranching families. We would have to buy out their so-called grazing rights—actually privileges—and permanently retire the allotments. For the good of the communities involved, this would need to be done carefully and generously and compassionately.

Tonino: It’s worth pointing out that the 1964 Wilderness Act allows grazing. Congressionally designated wilderness areas are off-limits to motors, roads, mountain bikes, drones, strip mines, and wind farms, but not cows.

Davis: Livestock just don’t belong on these lands. They eat too much of the wild forage, meaning there’s less food for the native grazers and browsers. They also trample and erode stream banks. Cows are just death on streams. In the arid West, wetlands are rare and rich in biological diversity. Springs, especially, are home to lots of endemic species of snails and insects and plants.

Of course, one of the most pernicious effects of ranching on public lands is that the culture around it often bitterly opposes predators such as wolves, cougars, eagles, hawks, coyotes, and some smaller carnivores as well. One of my closest friends is from a ranching family in Wyoming. It was his grandfather’s unquestioned habit to carry a rifle in the pickup truck and shoot predators on sight. That’s what people in his family were raised to do. Not all ranchers are that way, of course. I’ve been privileged to know some who align their work with the creation of wildways. But I’m afraid the majority remain opposed to carnivore recovery.

And the problem isn’t just with individuals like ranchers, farmers, and homeowners. It’s wildlife-management agencies too. These agencies are heavily influenced by hunters and anglers. Nothing against those folks, but they should not be allowed to dominate wildlife policy. As long as wildlife governance is dominated by hook-and-bullet interests, it will be very difficult to achieve wolf and cougar recovery.

Tonino: What role does active reintroduction of extirpated species play in rewilding?

Davis: When we’re talking about reintroducing a species, we’re actually talking about reintroducing specific animals. That’s too easily forgotten. Reintroducing wolves to Colorado, for instance, necessarily means dealing with wolf families and individuals—animals who have feelings, who have loved ones, who may suffer due to our efforts. It’s quite likely that a number of the first wave of individuals reintroduced will die: they may attempt to return to their original homes; they may be poorly adapted to the new place; they may get attacked by humans who claim the land for themselves. It’s a challenge for them.

That said, I do support the reintroduction of certain species to certain areas after careful studies have been conducted. We need to affirm that the habitat is of high- enough quality and that the individuals aren’t just going to get shot or trapped or hit by cars right out of the gate. Education of the human population is really important. You’ll never get full acceptance, but if most people accept or even embrace the reintroduction, there’s a good chance it can work. All of this takes time, lots of time.

Here in Adirondack Park, there’s evidence that natural recolonization by wolves could happen if we secured and connected enough habitat. A couple of years ago a large canid that a hunter thought was a coyote was shot near Cooperstown, New York. When Joe Butera, who runs the Northeast Ecological Recovery Society, saw a photo of this particular animal on social media, he immediately thought: That looks like a wolf! So he contacted the hunter, a conscientious person, who invited him to come see the carcass and take some tissue samples. They showed 98 percent wolf genetics and a 2 percent mix of coyote and dog genetics. Our coyotes in the Northeast are substantially larger than those in the West. They have up to one-third wolf DNA already and are starting to show wolf-like behavior, such as hunting in packs. If we can protect the habitat, the canids will work out the rest.

Tonino: The classic line “Nature abhors a vacuum” comes to mind.

Davis: With wolves, yes, they will fill the vacuum if we protect enough habitat. But cougars are different. I understand from my scientist friends in the field that male and female wolves both disperse widely. In 2014 I actually saw a female wolf named Echo on the North Rim of the Grand Canyon—the first wolf seen there since the 1940s. She had come all the way down from Yellowstone, some 450 miles. Tragically she was shot not long after that, in Utah.

Cougars have a different pattern. The males range widely, whereas the females typically like to settle near their mother. But, as always with wildlife, there are exceptions: I once tried to retrace the documented travel route that a female cougar had taken from the South Rim to the North Rim of the Grand Canyon. It was thought that only males would willingly swim across rivers, but this female was undeterred by the Colorado.

So possibly, over generations, cougars could travel eastward from the Black Hills of South Dakota and recolonize the Appalachians and Adirondacks. But I think the chances of that happening are vanishingly small. There are too many roads and guns between here and there. Plus the Great Lakes are a huge natural barrier to movement. No cougar is swimming across Lake Michigan! They either need to go across the Upper Peninsula of Michigan or north through Canada, because going south into the United States would be basically fatal.

Tonino: In your scouting adventures on the Eastern Wildway and the Spine of the Rockies Wildway, your stated goal was to see through the “wild eyes” of a carnivore. Were you successful? And what did you see?

Davis: I tried to imagine looking through the eyes of a cougar on TrekEast and the eyes of a wolf on Trek- West. I wanted to know: Would it be possible for a cougar to make it from the Florida Everglades to the Gaspé Peninsula in Quebec? Would it be possible for a wolf—or, more realistically, a lineage of wolves over time—to make it from Sonora to British Columbia? What parts of these wildways allow safe passage? What parts are badly broken and need mending? Maybe I didn’t truly see through the eyes of those creatures, but traveling by foot, day after day, certainly gave me a better appreciation of their needs.

For instance, when I would come upon a busy highway, particularly in the overdeveloped states of the Eastern Wildway, I would feel the threat viscerally: This is a major barrier, and a potentially lethal one; cars are screaming past in both directions; I don’t want to be here! A fair amount of time on TrekEast I had to bicycle, because I was sticking to a schedule, meeting groups and giving talks along the way. Also there’s so much private land in the East that it’s difficult to legally traverse the Appalachians on foot unless you stick to the Appalachian Trail, and that wasn’t the goal of the project. On my bicycle I was able to make progress because I went with the traffic on the roads, which isn’t an option for wildlife. Too many of our landscapes are simply impermeable.

Creating an Eastern Wildway remains possible in theory—there’s enough forest that it could be knit back together—but it will probably require something close to a national consensus, and it’s extremely difficult to achieve a national consensus on anything these days. Although just about everybody appreciates wildlife at some level, many sportsmen care only about grouse and deer and trout. That could change, though. The “disagreeable” species can become agreeable if we look at them from a different angle. Our value systems aren’t set in stone.

Tonino: Tell me about working on the Split Rock Wildway, a regional project here where you live.

Davis: It’s helped me realize that the Eastern Wildway will be built minicorridor by minicorridor, local pieces adding up to establish regional connectivity, regional pieces adding up to establish continental connectivity. It’s like doing a jigsaw puzzle. The overall goal is the picture on the box, but the creation of that picture is achieved by patiently, doggedly putting the pieces in place. Each piece is unique, and many groups and individuals need to be involved, but we have to always keep that big picture in mind. The land-trust community needs to do a better job of thinking at a larger scale and integrating its acquisitions so that the pieces of the puzzle do connect. By and large, corridors in the East are assembled from private lands, and private- land conservation is expensive. I’m on the board of Eddy Foundation and Champlain Area Trails, two of the land-buying entities in the fifteen-thousand-acre Split Rock Wildway, and I advise them on what land to acquire and protect. We’re about halfway there. The land trusts have been slowly filling in the gaps, working westward toward the High Peaks. Split Rock Wildway is hemmed in by a lot of farmland to the north and south, and of course it’s divided by some dangerous roads.

Tonino: Does your thinking get down to the granular scale—for instance, helping a salamander or frog cross one of those roads?

Davis: In addition to removing invasive species, I do take the time, when riding my bike, to stop and help salamanders across roads. It’s not part of some larger plan or program, but it feels meaningful to me. I keep a pair of heavy work gloves in the back of my truck so that, if I’m driving and I see a snapping turtle crossing the pavement somewhere, I can help it to safety. This is the northern edge of the timber rattlesnake’s range, and a number of times I’ve escorted them across nearby Lakeshore Road.

Tonino: I like reptiles, but I’ll admit to being sort of scared of rattlesnakes. Is fear a major hurdle for the rewilding project?

Davis: Absolutely. In his book Where the Wild Things Were, Will Stolzenburg writes that the deep-seated fears many people have toward big, toothy animals are legitimate and ought not be dismissed. Those of us in the conservation community probably don’t feel much fear. For a lot of folks I know, nothing could be more exciting or welcome than crossing paths with a grizzly bear. But Stolzenburg reminds us that fear is natural, instinctual: there was a time when Homo sapiens genuinely had to worry about being eaten by predatory megafauna. The only way to get over that hurdle is with public outreach and education.

Tonino: You’ve said that the animal you most fear is the tick. How come?

Davis: I’ve had Lyme disease at least twice, the second time quite seriously. My hips went bad, and now I’ve got a pair of titanium hips. Admittedly I’ve lived a very active life—carried a lot of heavy packs, jumped off a lot of ledges—and the cartilage was already worn down. But I’m convinced the Lyme disease finished them off: there was a ton of swelling in the joints. Doctors debate whether chronic Lyme disease is real, but from observing some of my friends’ ongoing struggles, I’m inclined to believe it is. In any case, tick-borne illnesses are serious business.

Research out of the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies in Millbrook, New York, has shown that having a full suite of native predators lessens the likelihood of zoonotic diseases spreading, including Lyme. It’s yet another example of a complex cascade: Small rodents often carry the ticks that give us Lyme disease, and foxes are the most effective mammalian predators of small rodents, but their numbers tend to decline when coyote numbers increase. Wolves see coyotes as direct competitors and will chase them off and even eat them. Now put it all together: more wolves lead to fewer coyotes, which lead to more foxes, which lead to fewer small rodents carrying the ticks that spread Lyme disease.

The grim irony of our cars and roads is that, as they create connectivity and freedom of movement for us, they do the opposite for wildlife. The very means we employ to go places makes it much harder for many other species to go places.

Tonino: Your home here inside Split Rock Wildway is called Hemlock Rock Wildlife Sanctuary. Is that a formal, legal designation or just your personal name for this place?

Davis: It’s both. I named these fifty-five acres, which are officially protected by the Northeast Wilderness Trust under a forever-wild easement. Where we’re sitting right now, on the deck of my cabin, there’s a roughly one-acre homestead area that also includes my outhouse and shed. But the bulk of the land is forever wild, meaning I’m not allowed to log it, subdivide it, or put up additional structures. If the cabin gets smashed by falling trees, as happened in a microburst in 2010, I’m allowed to rebuild in the same dimensions, but I’m not allowed to expand the footprint or put in utilities. I’m allowed to use only hand tools to cut firewood. And I keep my cats, Wren and Fen, indoors to protect the songbirds who share this place with me.

Tonino: Coexistence seems to require a shift in our perception of the land, an appreciation that it was never “ours” in the first place. How do we begin to see and feel ourselves as living within wildways that once existed in North America but have been busted to pieces and emptied out?

Davis: I use the phrase “wild neighbors” often, and I really do see this as a neighborhood. I try to be a good neighbor. I’m very fond of the local songbirds and frogs and squirrels and bats. In fact, there’s a bat listening in on our conversation as we speak: year after year they roost in the eaves of the cabin right above your head. I seldom see him or her, but I see the scat on the deck most mornings. Sweeping it up is an important part of my life here.

Conservationists need to encourage coexistence but also not forget about setting aside big, wild, connected spaces where humans do not live. That’s crucial. We need more wilderness, more national parks, more places where “man himself is a visitor who does not remain,” as the Wilderness Act puts it. And, adjacent to these places, we need places like Split Rock Wildway that are only sparsely inhabited by humans.

My most recent book, Split Rock Wildway, is a guide to my neighbors—past, present, and future—ranging from the mink to the moose to the northern goshawk to the porcupine to the extirpated cougar to the extant-but-struggling American eel. I write about how we might live peaceably among these animals. For instance, on a warm spring night when it’s raining, don’t drive—and if you have to drive, proceed as slowly as possible—because there are frogs and salamanders crossing the road, and they stand no chance against your tires. If you really tune in and appreciate that you are recklessly slaughtering the amphibians of your neighborhood, who are merely trying to get on with their lives, maybe you can adjust your behavior.

The tragedy of roadkill can be a unifying issue. Nobody likes to run over a red squirrel or a garter snake. Structural engineer Ted Zoli has said that wildlife crossings are the best way to end the tragedy of roadkill. That’s a noble goal. It’s crazy that we take the everyday carnage for granted.

Tonino: What about outdoor recreation—or as some spell it, wreckreation? Is it compatible with conservation values?

Davis: There’s definitely a tension between rewilding and the outdoor-recreation industry. Nevertheless, I believe that quiet, nonmotorized recreation can lead to increased appreciation and, in turn, positive action on behalf of wilderness and wildlife. I admit a bias: I’m an avid hiker and paddler and cyclist. But I would never ride my bike in a wilderness area. That’s illegal, not to mention extremely selfish. It pains me to hear that some mountain bikers oppose wilderness designation because they want to be able to ride in choice backcountry terrain. There are hundreds of thousands of miles of US Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management roads that provide perfectly good riding. Conservationists and mountain bikers ought to be allies.

I have much more trouble with motorized recreation. Though I acknowledge that there are plenty of caring, nature-loving people who like to drive ATVs and snowmobiles, I wish these machines were not allowed on public lands. The harmful impacts range from erosion to harassment of wildlife to pollution to sparking unnatural fires. To me, motors disconnect us from wild nature, and connection is of course what rewilding is all about. They make things too easy. I bought a used, four-wheel-drive truck a couple of years ago. At the wheel of that thing I understand why people get a feeling of power, that they can go anywhere. But we should absolutely not be going to many of the places that we can go.

Tonino: What role do private money and private land play in piecing together a wildway?

Davis: A big one. In my ideal world we wouldn’t have land ownership as it’s commonly practiced, but in this society, where private-property rights are sacrosanct, one of the best things people of means can do is buy land and protect it with solid conservation easements. The wealth disparity in the United States is appalling, sinful really, but if rich folks want to purchase land and save it, that’s fine by me. It’s only a small minority of millionaires and billionaires who do this, and in most cases they’re doing it quietly, but they are out there, thank goodness. Doug Tompkins, who made a lot of money with apparel companies like the North Face, was one of the cofounders of the Wildlands Project with Dave Foreman and Michael Soulé. He deserves a lot of credit, along with his wife Kristine, for bringing wildlands philanthropy to bear on the rewilding movement. Doug passed away in 2015 in a tragic kayaking accident. Kris remains as active as ever. Tompkins Conservation has been central to the creation or expansion of fifteen national parks in South America.

I used to work for the Tompkins organization, and I’ve had the privilege of traveling to Chile and Argentina to see how they go about restoring missing and diminished species there. They’re very methodical, very strategic, very smart. One of their most successful rewilding efforts is in a place called Iberá Park, an enormous wetlands complex in Argentina. Instead of starting with the jaguar, a controversial predator, they first reintroduced the giant anteater, an animal that just about everybody likes. And now they’ve released jaguars! Maybe in parts of North America we can follow their lead and start with lovable otters instead of wolves? Some have suggested that we talk about Canada-lynx restoration before cougar restoration, because the lynx isn’t so scary.

Tonino: In 2004 Dave Foreman said that the “bold, hopeful vision” of rewilding was achievable in twenty years. Two decades have passed, and the vision obviously has not been achieved, but your enthusiasm for the cause seems undiminished.

Davis: One reason we’ve lost ground over the last twenty years is that conservation has become a partisan issue. That hasn’t always been the case. Historically some of the best conservation leaders in Congress were Republicans. Nowadays that’s far from true. This may be partly the fault of conservationists. We may have sided too frequently with the Democrats, which led the Republicans to ignore us.

The shift was already underway when Dave Foreman was writing Rewilding North America, but it’s worse now. Conservationists generally have to assume that Republicans won’t support us and will likely fight us. As long as one of the two main political parties sees conservation as the enemy, we can’t do much. We need to somehow make conservation nonpartisan again and appeal to people’s inherent interest in nature, which too often gets lost in all the arguing and confusion.

That said, the fundamental job of a conservationist is not to fix civilization but simply to save as much ground as possible. Even as the world seems to be crumbling around us, even as our anxiety and fear grow, we can try to protect the ecosystems, the self-willed land.

In the short term there are lots of tangible examples of rewilding work prevailing against long odds. Nancy Stranahan is one of my heroes. For decades she’s been buying land through her group Arc of Appalachia. She’s saved tens of thousands of acres—mostly in southern Ohio, of all places! The habitat there is largely gone, yet she finds the little pieces of remaining forest and draws them together. Nancy Stranahan is not wealthy—she’s raising money from other people—but her success has been so great that she’s branched out into West Virginia, which is among the most promising states east of the Mississippi River for rewilding: largely forested, very mountainous, with quite a bit of public land, relatively low human population density, and private-land prices that are still relatively affordable.

We need people from all walks of life and all backgrounds: writers, bureaucrats, teachers, field ecologists, tradesmen. Heck, there’s plenty of work for heavy-machine operators—ripping out derelict dams, putting in wildlife crossings.

Tonino: Can we end by celebrating animal locomotion for a minute? Birds soaring, fish darting, squirrels scampering in the forest canopy, elk running in the meadows, worms tunneling underground—the diversity is incredible! Evolution appears, from a certain angle, to be a process of inventing surprising ways of moving.

Davis: From my time trekking the Spine of the Continent, I recall descending Boulder Mountain in Utah alone, late in the day, and seeing a teal, a small duck, flying rapidly, and a bald eagle hot on its tail, closing the distance. I was stunned by how skillfully, how fluidly, the teal swerved and dropped and slid across a little pond—and, in doing so, ditched the eagle, which veered away. The duck went from fleeing for its life to just placidly paddling along. The power of that eagle and the agility of that duck are with me to this day.

I’ve had many thrilling moments watching animals in motion: salmon swimming up a mountain stream, pronghorn sprinting fifty miles an hour across a valley of sagebrush, grizzly bears lumbering through the forest, peregrine falcons diving down cliff faces. Birds stand out. Mary Oliver has a lovely poem about the perfection of a kingfisher diving. Fairly often here on the beaver pond, I watch wood ducks and mallards and teals come in for a landing, and I always find it inspiring: that angle, that smoothness, that grace.

Tonino: But you’ve never seen a cougar.

Davis: No, not yet.