This month marks The Sun’s twenty-fifth anniversary. As the deadline for the January issue approached — and passed — we were still debating how to commemorate the occasion in print. We didn’t want to waste space on self-congratulation, but we also didn’t think we should let the moment pass unnoticed. At the eleventh hour, we came up with an idea: we would invite longtime contributors and current and former staff members to send us their thoughts, recollections, and anecdotes about The Sun. Maybe we would get enough to fill a few pages.

What we got was enough to fill the entire magazine.

Though we haven’t devoted the whole issue to the anniversary, we have allowed the section to grow beyond our original plans. After seeing the pieces, we felt that our readers would enjoy them as much as we did — for the information about the magazine’s history, for the glimpses into the writers’ lives, and (not least) for the quality of the writing.

Still, our one concern is that some of the contributors to this section have been more than generous with their compliments. In the end, we’ve decided to weather their praise with a mixture of humility and embarrassment, like the guest of honor enduring a toast.

Before you begin reading, there are two items that should be clarified. (1) After initially occupying an attic room over a bookstore, The Sun has had its offices in two different houses: the first was one story, yellow, and in disrepair; the second (its current location) is two story, white, and in good shape. And (2) Sy Safransky, The Sun’s editor, no longer smokes cigarettes, and even when he did, he didn’t inhale.

This is the first issue of The Sun, from January 1974. (The full name then was The Chapel Hill Sun.) It came out at the height of the energy crisis, when people were waiting in line at gas stations. The cartoon is by Mike Mathers.

John Rosenthal

Chapel Hill, North Carolina

First published December 1976

I had seen Sy around Chapel Hill in the early seventies, a thin, bearded man in sandals hawking what looked like a pamphlet he’d stapled together. It was called The Sun and cost twenty-five cents. One day, I had a quarter and bought one. Handing Sy my money, I said, “It’s good to see someone selling poetry on the streets,” but I didn’t really mean it. Most poetry sold on street corners is awful. When I read Sy’s writing, though, I thought it was pretty good. Better than it had to be.

A week or so later, we saw each other in a laundromat, and Sy courteously introduced himself. I remember the extremely open expression on his face, and how he looked me in the eye and didn’t stop looking, even after we’d shaken hands. This was unusual. It was as if he was disarming me before I could gather together the various elements — wit and cleverness and cynicism — of my social persona. How nice.

Our friendship began at that moment.

I complimented Sy on his writing, and he thanked me but said he wasn’t really interested in filling the magazine with his own work. He spoke of a vacuum in the publishing world: There were too many voices being ignored, too many spiritual concerns not being addressed. There were better ways of getting at the truth than through the usual polemics — at least, he thought so. And he spoke of the sun as a metaphor for what he wanted to do: bring light where there is darkness. He also referred to the disinterested, non-elitist nature of sunlight, how it shines on everybody.

There was no ideological flavor to what Sy was saying, or to the manner in which he said it. He simply talked about providing an alternative forum for those who didn’t think like everyone else. When I warmed to the idea — who wouldn’t? — he asked if I would be interested in contributing a photograph or maybe a review to an upcoming issue.

Since that day, I’ve published scores of photographs in The Sun, and almost everything I’ve ever written has either been published or reprinted here.

Twenty-five years has gone by. There is still no reigning ideology, only the broad notion of a magazine filled with all sorts of voices, many of them unknown, that we don’t encounter anywhere else; a magazine that doesn’t sacrifice truth to optimism, or underestimate the sorrows of existence.

Bob Rehak

Chapel Hill, North Carolina

Production Manager/Manuscript Reader 1993–1998

I showed up for my job interview a few minutes early, dressed in a dark blue suit I’d pieced together at the Big and Tall Men’s Shop in Ann Arbor. Unlike Michigan, North Carolina can be hot in October; by the time I got to the Sun office, I was sweating like someone trying to defuse a bomb.

Sy leaned back behind his desk, his eyes friendly razors behind round wire frames, and listened to me burble earnestly about my job history, my goals, my strengths and weaknesses. I was simultaneously trying to read his expression (patient? credulous? bored?) and ignore a moist, gummy sensation along my spine that suggested I’d become stuck to the chair.

Sure enough, when I got back to my friends’ apartment, I discovered that my sweat had partially dissolved the chair’s varnish: my shirt bore, between the shoulder blades, an arc of brown, like a cauterized wound. (That would explain the ripping noise when I’d gotten up to shake Sy’s hand.)

That night I filled out a proofreading test and lined up three additional references. I went back to the office the next day — dressed more comfortably — and took a typing test. Then Sy shook my hand again and wished me a good flight back to Michigan. A week later, he called and asked me to come work for him.

At twenty-seven, I was painfully ready to grow up. Over the next three years I learned to wake at 8 A.M., drink my coffee black (coffee is to The Sun’s daily operations what peyote is to certain Native American religious rites), and paper-clip manuscripts according to Sy’s exacting standards. He suggested that even mundane office work could be done mindfully, like a monk sweeping the monastery floors, because the care brought to lowly acts trickles upward to the highest levels of the endeavor.

I changed in other ways. I lost seventy pounds and my girlfriend back home. I found another partner — this one, maybe, for life. I rode out the manic-depressive cycle of monthly magazine production: the frustration of deadlines and technical glitches; the neurotic worry that maybe today is the day Sy will realize he hired the wrong guy; the fierce pride in each new issue, followed by the obsessive search for typos. (Spotting one was like finding a lump in my scrotum.)

When it was time for me to move on, Sy, with his usual mix of generosity and mischief, gave me a big TV and a box of candy — props of the leisurely bachelor’s life of which I sometimes imagined The Sun had cured me. But he knew me better than that.

Josip Novakovich

Blue Creek, Ohio

First published June 1989

Over the years, I’ve learned that The Sun will publish stories and essays most editors cringe at, especially ones about death, disease, war, and other terribly uncomfortable subjects. So when my friend Richard Duggin showed me his vividly detailed story about cremating his father’s corpse [“Easter Weekend,” April 1993], I said, “Send it to The Sun. They’ll love it.” And they did. Another friend of mine, Ivor Irwin, wrote a story whose protagonist was the son of an Auschwitz survivor and kept his dead wife’s pubic hair in a plastic bag to sniff [“Sonderkommando,” May 1991]. Several editors were too squeamish to publish it, but Sy wasn’t.

The Sun is the only magazine with an aura of spirituality that doesn’t have a forced happiness about it. It presents unflinchingly the most powerful, and sometimes terrifying, aspects of our lives. Ironically, the awareness of such horrors can actually make each moment in life not only more meaningful, but perhaps happier, even holy in its uniqueness and brevity.

This magazine also inspires more camaraderie than any other I know. There should be Sun clubs, where we could sit naked in saunas and talk about how our relatives died, and the diseases that torture us, and the various ways in which we are liars and cowards. We’d have a great time.

Stephen J. Lyons

Pullman, Washington

First published February 1995

The first time I submitted work to The Sun was on July 24, 1990. Twelve days later, I celebrated the first anniversary of my divorce with a counseling session where I spent eighty dollars and helped my therapist deal with some issues she was having. “I almost feel like I should be paying you,” she said cheerfully, as I wrote a check that had a fifty-fifty chance of clearing. I didn’t mind, though. She was much happier than when we’d begun, and because I am codependent, this made me feel better, too. For the first time in months, I actually whistled.

Twenty days later, the first rejection letter from The Sun arrived. That same day, I had another counseling session and was led on a guided meditation to meet an eight-year-old version of me. “Go up and greet him,” the counselor urged. “Is he glad to see you? What’s he doing?” I wanted to answer, He’s picking his nose, craving a hot dog, and thinking about the White Sox, but I knew this wouldn’t make her happy, so I said he was alone — abandoned, even — and feeling sad. I opened my eyes just a sliver and saw her writing furiously. When the session ended, I wrote another wobbly check. Again, my therapist seemed in a much better mood than before. We were starting to get to the bottom of something — like my savings.

Sy must have written an encouraging note on that first rejection letter, because I quickly mailed another submission, on September 6. (I keep very detailed records.) Weeks passed, then months. In the meantime, I tried another counselor. She was a primal-scream therapist. “Louder!” she screamed. “I want you to purge your pain up through your solar plexus and out through your primal voice. Louder!” But each time I tried, I imagined my best friends from high school in the next room, laughing hysterically. I couldn’t make that therapist happy.

On December 10, 1990, I received my second rejection letter, this one a personal note on a beige piece of paper: “Stephen, although I don’t want these for The Sun, I found them lyrical and engaging. Please keep us on your list for future submissions. Sy Safransky.”

Lyrical! Engaging! He even thought I had a list. Because I knew acceptance was close — and because I didn’t want to disappoint Sy — I kept submitting.

For the next five years, I received a steady stream of rejection letters. Sometimes Sy would write a line or two of praise, sometimes not. During that time, I heard of a therapist who evaluated your mental state based on how you reacted to a little white poodle she kept in her office. (Or maybe it was how the dog reacted to you.) Although this was tempting, I held off.

The year I stopped therapy, The Sun published my essay “My New Neighbors” [February 1995]. Seven acceptances would follow, and no more counseling. The way I see it, whatever dysfunctions I have translate into the kind of writing The Sun wants. If I become too stable, I may never hear from Sy again.

Hal Richman

Hubbards, Nova Scotia

First published June 1974

Reviewing my pieces in the early issues of The Sun, I found several on right livelihood, one on religion (with a cartoon of Moses wearing boxer shorts), a recipe for peanut-butter cookies, and a somewhat embarrassing essay titled “Confessions of a Male Chauvinist P–g” [November 1975]. (I don’t mind revealing the existence of this last item, as I assume there are no back issues that old left for sale, and, now that I’m fifty-two, most women see me as a dead tree in the forest of men.) I was struck by the shallowness of some of my ideas and wondered if I’d just been stuck in the goo of the counterculture. Hard to tell from a distance of twenty-five years.

My first memory of Sy is of meeting him in a now-defunct juice bar and watching the excitement in his eyes when he told me he was starting a magazine. (He does not remember this.) My relationship with The Sun changed over the years to reflect my state of mind and my idea of what life is all about. As I moved into Buddhism in the late seventies, I saw The Sun as indulgent, not to the point. As I moved into software in the eighties, and then management consulting in the nineties, I felt the epitome of human expression was the tight prose of proposals and “consulting deliverables,” and that the writing in The Sun was like Jell-O overflowing its mold.

In the last few years, however, I’ve become disenchanted with the world of reports and jargon and have begun to understand that metaphor and symbol are the only tools we really have in the search for meaning. Sometimes the way is clear, sometimes cloudy, but it is a journey always taken by the writers in The Sun.

William Timmerman

Dallas, Texas

First published July 1979

The first time I picked up The Sun was in the summer of 1977 in Maggie Valley, North Carolina. I was nursing a hangover at the home of two women, where I’d passed out the night before. I was having one of those long toilet sessions and reading Sy’s reprint of a James Dickey poem about a stewardess who fell out the rear emergency door of a 727. The idea behind the poem was that the time it took the reader to read about her fall was also how long it took her to fall to earth from thirty-five thousand feet. (It was also exactly how long it took me to go to the bathroom that morning.)

Years later, I sat in The Sun’s office, a little one-story house on an overgrown gravel parking lot, and sweated for days, trying to transcribe a rambling three-hour speech by Ram Dass. It was hell and taught me never to be a professional transcriber, no matter how much praise or marijuana I am given. I think it also gave me a bad back and terrible pine-pollen allergies that year — both the worst I remember having in my life.

And The Sun was definitely responsible for my picking up that nasty cigarette habit that damn near killed me. Sy would sit in his office contemplating his next article and smoking one of those ass-kicking French fags that John Lennon smoked, and I loved the way the smoke hung in the air with the sound of his old typewriter — the two just went together. So I picked up the habit, and I blame it all on Sy to this day.

John Taylor Gatto

New York, New York

First published June 1990

What I liked about my first issue of The Sun was that it made me furious. In it, there was a statement of such stupid, whining self-pity I wanted to put a dead rat in the writer’s toilet. And the Correspondence section, my favorite part of any magazine, seemed filled with the shrill screeds of small-minded, mushy-thinking, politically correct bigots who fancied themselves enlightened. Dante would have consigned them to the most gruesome comers of his Inferno.

Still.

In a world where I could barely hear the birds for the constant spinning, spinning, spinning of spin doctors writing for the New York Times or the so-called news magazines, The Sun was something different. Not one of the freaks and philosophers who graced its pages ever tried to spin me. They were always so convinced of the justice of their cause, they had no time to waste confounding me with spin. They said it like they thought it was. It wasn’t that way, in my opinion, but there was something refreshing, admirable, and characteristically American about people having their say and to hell with what everyone thinks. I found myself actually reading The Sun long after the piles of unread New Yorkers, Atlantics, and Newsweeks had gone to the landfill to poison the ground water with their foul, leaching inks.

The Sun helps me to remember that America is about argument, not consensus; that we don’t want or need artificial peace and harmony but real-life, knockdown, drag-out contention. Our nation has become an empire, but The Sun reminds us of what it was intended to be — and still could be if we learned to sabotage the empire instead of ignoring it, or even screaming at it. Sovereignty needs to be restored to the people — not just the best people or the richest, but all the people. We need forums in which to argue with each other and to organize against concentrations of power.

So The Sun pisses me off, and that’s why I like it. I need to be pissed off. And so do you.

Edwin Romond

Pen Argyl, Pennsylvania

First published December 1988

It was late morning, and the bus to New York City was half empty. One seat up and across the aisle, I saw a passenger reading the current issue of The Sun, in which I had a poem. With a strange excitement, I realized that this man was only one page away from my poem. I was about to witness what I’d always imagined: someone I didn’t know reading my work.

I tried not to be too obvious about staring over his shoulder. Finally, he turned to the page that contained “Macaroons” [May 1995], and I followed his eyes as he read. He was taking his time, reading carefully, but I couldn’t detect a reaction on his face. I thought of tapping him on the shoulder and revealing myself as the author, then wisely decided against it.

I don’t think I’ll ever be as grateful for anything involving my writing as I was for the minute or so that stranger devoted to my poem. It gave me a sharp realization of what happens each time an issue of The Sun is sent out to the public: people actually read this magazine, ponder its contents, perhaps even live a little differently because of what they find in its pages.

John Cotterman

Hillsborough, North Carolina

Production 1987–1992

When considering a move to Chapel Hill in 1980, I was ultimately persuaded by two factors: the great pumpernickel bread at the Chapel Hill Bread Shop (no longer there) and a small local magazine called The Sun (still there). Within a few months I found myself first working for and then buying the typesetting firm that shared an old yellow house with The Sun. Sy and I made an arrangement: free rent in exchange for the use of my typesetting machine. In those days, the magazine was typeset by volunteers who had to work around my business hours. I remember one woman who was so dedicated that she’d come in on cold mornings at 6 A.M. I’d have to growl and chase her out so I could start my day. (Four years later, I married her.)

The sixty-year-old house we shared was quite a place. The roof leaked, the pipes froze, the floors sagged, the rats scurried, the pigeons shat. Those were our days of involuntary simplicity. Sy had become quite skilled in making his annual plea to Phil the landlord to hold the monthly rent at $250. Phil once commented that he earned a lot more money than Sy but was probably a lot less happy.

I had little doubt The Sun would last this long; I knew Sy’s tenacious spirit too well.

In February 1976, The Sun began calling itself “North Carolina’s Magazine of Ideas.” The subtitle (which was soon shortened to “A Magazine of Ideas”) lasted until the issue you’re reading, where it’s been dropped.

Janice Levy

Merrick, New York

First published December 1991

I took a writing class in college because it was the only elective that didn’t interfere with watching General Hospital. The professor read our work aloud, stopping abruptly when he was bored. None of my stories got past his first yawn. He advised me to get a better sex life; then my stories would sizzle, he said. He added that he could help me with both.

Some years later, I came across the Writer’s Market, with its many listings of places to submit manuscripts. I had no time to actually investigate any of the publications, so I scanned the titles with my fingertips, as if the page were a Ouija board. My pinkie tingled when it got to The Sun. That’s it, I thought. Good name. Light, hope, eternal, warm, nurturing. I sent in one of the yawners. “A beautifully written story,” Sy Safransky wrote back. “Some of your images just knock me out. I am impressed by your talent.”

My heart moved from its regular place. With that acceptance notice in hand, I raced around the bases of the schoolyard baseball diamond, hearing cheers in my head and thinking of Casey Stengel’s description of Mickey Mantle: “[He ran] so fast he didn’t even bend the grass when he stepped on it.” Suddenly, I had a résumé.

That was seven years ago. My next three stories were published in anthologies by editors who had read my work in The Sun. My résumé has since grown to a full page of credits, including five children’s books.

Writing is like taking off your clothes in a crowded room and turning around slowly — twice. That’s why I like The Sun. It publishes the secrets people choose to share. With dignity. With respect. I never wanted to be a writer. My childhood dream was to play centerfield for the Yankees. I’m still waiting for the call, but in the meantime I’ve got something to keep me busy.

And, oh, by the way, if that professor is reading this: I did get a better sex life.

Al Brilliant

Oakland, California

First published July 1983

I don’t remember when I began reading The Sun. It’s been probably twenty years, at least. I also don’t recall how many of my poems The Sun has published, but I do know that my proudest moment so far as a writer was when my poem “Oil” [July 1983] appeared in the anthology A Bell Ringing in the Empty Sky: The Best of The Sun. And I certainly remember the first time I met Sy Safransky.

At the time, I was living in Greensboro, North Carolina, only fifty miles from Chapel Hill. Although I had traveled to Chapel Hill on occasion, my path and Sy’s had never crossed. We would meet when we were meant to meet, Sy said.

One of my trips to the Chapel Hill area was to see the singer-songwriter Ferron in concert at a huge Gothic cathedral on the campus of Duke University. I’d enjoyed Ferron’s music for years and had even sent some tapes of it to Sy, who had never heard of her work. On the night of the concert, I drove over from Greensboro, but I couldn’t find my way around the enormous Duke campus. As I parked my car, another car pulled in behind me. “Say,” I asked the man who got out, “do you know where Duke Chapel is located?”

Out of the darkness came the reply “Are you Al Brilliant?”

Yes, it was Sy, meeting me by happenstance, just as he had predicted.

Sparrow

Shandaken, New York

First published December 1981

The Sun first rose in my life on April 8, 1978 (this is a guess), at Mother Earth Natural Foods in Gainesville, Florida. My first thought was: I want to write for this paper! (At that time, The Sun was more papery — even its cover was soft and pliant.) But I did not write for The Sun, because I was a hippie, and hippies don’t write for publication. Hippies write in their diaries, and they write letters to their more literate friends who finished college.

But in September of that year I returned to New York City, and six months later I wrote my first Readers Write piece, about my arrest in front of General Electric headquarters protesting against nuclear power. My goal in writing this piece was to politicize The Sun — and I succeeded. The Sun is now the foremost organ for Socialist thought in America. [Sy, please don’t cut that last line!]

I discovered that one may write about all earthly phenomena for this magazine. I wrote about my appliances. I wrote about peeing on my girlfriend. I became hated by one-fifth of The Sun’s readers for writing about appliances and about peeing on my girlfriend.

My most satisfying moment was when Sy printed my photo, and a reader wrote in, “Sparrow, I always thought you were a lesbian in a black leather jacket.”

And, oh yes, everything of mine Sy rejected, he should’ve rejected.

Dana Branscum

Hope, Maine

Assistant Editor 1987–1990

I dreamed I met Sparrow on a New York City street. It was perfectly deserted. He said, Tell me about Sy. Tell me the true story, the whole story, and nothing but a story.

I said, Sy once decided his daily breakfast had too many ingredients: nuts, yogurt, fruit, grain. Too much.

What was the grain? said Sparrow.

Grape-Nuts.

So he switched?

Yes.

To what?

Suddenly I was bored and saw quite plainly in his soulful brown eyes that Sparrow was bored, too.

Just give me the facts, he said.

I said, He’s funny, warm, wise.

Tell the truth, said Sparrow.

I said, He’s unyielding, exacting, nit-picky.

The truth, said Sparrow, the truth. And he began to dance.

I spoke cautiously, hoping to get it right. Very intense, very calm.

But Sparrow was dancing circles around me.

I sighed. I said: OK.

Sy loves to agonize.

Sy loves giant cookies — no sugar, but don’t spare the honey.

Sy loves his wife the way a wife wants to be loved.

Sy loves to be adored, and I once got really angry because —

The truth! cried Sparrow. The truth!

I said, The truth is Sy doesn’t even exist. He’s the alter ego for a fat, brilliant lesbian named Smudge. No, a small, soft, pudgy guy named —

I’m leaving, said Sparrow. I don’t have to stay in your dream if there’s nothing in it for me.

I stomped my foot, hard enough to squash something small that might have strayed beneath it, like maybe a poet wandering the city on the astral plane.

What do you want? I said. He straightens paper piles relentlessly and insists on keeping staples separate from clips separate from erasers separate from number-two pencils, and so on ad nauseam, tidy tidy tidy. And yet he lives in bluejeans, his beard is unkempt, and his last two or three shirt buttons always go unfastened.

Sparrow leaned forward: Two or three?

He has this little editor’s rhyme that he claps along to: “When in doubt, take it out.” He’s funny, very often, every day. He’s good at wordplay and self-mockery and the occasional searing sarcasm. He’s sad, very often, every day — a man who knows the feel of his own tears. He’s finally made friends with computers. He has a sex story that involves blueberries. He looks best in red and has an award-winning smile, definitely one of the best I’ve seen on a balding man with hair that tends toward ringlets.

Sparrow started rocking back and forth, chanting, The truth, the truth, the inside scoop. The truth —

I grabbed his shoulders to still him, looked him in the eye, and said, No really, Sparrow, it’s a great, great smile. You have no idea how badly I needed that smile when I met Sy. No one had ever smiled at me like that first thing in the day. No one had ever appreciated me the way he did. No one had ever seen me so clearly. Oh sure, he was annoyed by all those coffee and tea and bathroom breaks. Never mind that I worked more hours than I ever got paid for, never mind the pay was —

I had assumed an urgent tone and was considering a shaking tactic when I noticed I was holding an empty sagging coat, a wonderful worn tweedy thing with little orange specks dotted into a once-charcoal gray. I heard behind me the familiar staccato sound of a manual typewriter operating at full speed. I turned, and there was Sparrow in his shirt sleeves, seated on the curb, typing away just the way Sy does, that intent, feverish gaze fixed over flying hands. I couldn’t believe there existed two men who typed that fast with their index fingers.

I watched for a moment, basking in sweet nostalgia. Then I walked away toward the life I now live, perfectly satisfied, perfectly warm and content inside Sparrow’s coat.

Poe Ballantine

Hays, Kansas

First published August 1995

I never thought about sending a story to The Sun until I was digging holes for green ash trees one day with a botanist named Barb, who mentioned that a friend of hers “just got her Sun today and can’t wait to get home to read it.” I thought, This magazine must be special.

I sent them several stories before the editors accepted one. The Sun was quite different from all the other publications I’d worked with. First, they paid. Second, they edited. I wasn’t happy about the editing. I squabbled and balked. I threatened to withdraw my stories. When the first story finally appeared, it hardly seemed like I’d written it. But readers generally liked that story. Gradually, I realized I wasn’t half the writer I thought I was, that 80 percent of the changes the editors made were improvements.

I continue to send them work, and they continue to edit me — and, honestly, very often salvage me. In the three years since my first story appeared in The Sun, I’ve been in Best American Short Stories 1998, I’ve received many invitations for work from other magazines, and I’ve signed a book contract with Houghton Mifflin. Best of all, I’ve received dozens of letters from appreciative readers, very few of whom realize how much of the credit must go to The Sun.

[To the editors: Hope this isn’t too standard or dry. If you want, you can add the part about the time I fell out of a helicopter, took my Sun out of my back pocket, and made it into a parachute. Of course, the helicopter hadn’t taken off yet. But never let the facts get in the way of a good story.]

By July 1978, “North Carolina” was gone from the subtitle, and the magazine was featuring nationally known thinkers like Robert Bly. The Readers Write section — then called “Us” — had made its first appearance just three months earlier.

Colleen Donfield

Raleigh, North Carolina

Manuscript Reader 1994–present

Years ago, I sat underdressed and freezing on a bench on an elevated platform waiting for a BART train heading east out of Berkeley. It was late, I had just missed my train, and it would be a long wait for another. I had been with a friend, someone I had gone to school with in New York, and who was in nervous transition, like me. After living in grubby but happy exile for three years, writing and reading anything I wanted, I’d returned to the Bay Area and was feeling alarmingly uneasy and ungraceful, like a sulking adolescent. My friend was passionate, extremely intelligent, complicated, hyperarticulate, and probably a bit mad. As always, I was drained by her, but in a good way, more poured out than exhausted. Together we’d struggled to express what was happening to us, searching for “the word,” as we called it — the exact word for it: this life, this story, this street.

But now she was gone and I was alone and cranky. At our last stop of the night, I had purchased a magazine I’d seen around but had never read, published out of Chapel Hill, North Carolina. I don’t remember now what I thought of it then, only that I was alone in the cold on top of a windy black night, filling myself up again with words. I would look up at the sound of heels clacking down the platform, then look out over the track and the warning signs (DANGER! ELECTRIC THIRD RAIL!) to the lit houses below, the imprint of the words blurring my vision. I couldn’t possibly know that the magazine I held in my hands would soon come to give shape to my days, take over my house, and lodge permanently in my heart.

I was taking the train back to the suburb my husband and I had left San Francisco for, a small town where we lived for three years, in a different house every year. I was either pregnant on that platform, or about to be, or my daughter was already here and had gone to sleep that night without me; I don’t recall. But when she was two and my husband and I (mostly I) had grown tired of our California life, we moved to North Carolina. Soon after, at a temp job in a large research institute, I befriended a woman with a beautiful Southern accent and a complicated life, who was (still is, I hope) a writer. On her way out of town, she handed me the gift of her part-time job: manuscript reader for The Sun.

My first clomp up the narrow wooden stairs to Sy’s office was a fair harbinger of things to come. During the interview, the topics of conversation quickly became personal — our domestic setups, spouses, children, worldviews, religious and social backgrounds. It became clear to me that I could bring my giddy conviction to this warm, well-ordered room, and it would be not only safe here, but welcome. The word my college friend and I had searched for was spoken here — not just the heartbreaking beauty of it, but the life and death of it, the shades of its sorrow, the black humor of it.

Four years and a thousand clomps up the wooden steps later, after hours of deep and not-so-deep revelation, much laughing and sad reflection, I can no longer imagine working outside the realm of the word, can’t even imagine how other people do it (which means I have added “shortsighted” to the features of my personality). If someone asks casually, “What are you reading?” I become slack-jawed and disoriented. I am sure I know the name of every hopeful writer in the United States today, and I think every new name I hear belongs to someone who has submitted a manuscript.

By its nature and the nature of the submissions it elicits, The Sun both sustains me in my darkest hours and exacerbates my darkest fears. I worry incessantly over my daughter’s passage through life; on any old blue-sky day I can read three or more manuscripts about the death of a child. Recently my husband was diagnosed with cancer; suddenly, every story in the box contains a character with cancer.

I look out the window from the table where I work. I note that the UPS man has stopped wearing shorts, that yet another neighborhood dog has broken through his shock fence and is jogging down the street, that a neighbor is walking her new baby in a green buggy shaped like a sports car, that another is suspiciously home in the middle of the day. I pick up a manuscript and begin, opening again to the dying mothers, the sad-sack fathers, and their weirdly sprung children. Every one of them, every word, comes to me as if through the sound and smell of a windy black night pinpointed with light and thick with smoke from chimneys.

Joseph Bathanti

Statesville, North Carolina

First published January 1985

About five years ago, I read in a medical journal about a prison inmate who for years had literally pounded sharp objects into his skull: nails, thorns, miscellaneous shards of metal and debris. Alongside the article was an X-ray of the fellow’s cranium. The various sharp objects showed up in the ghostly photograph as dozens, perhaps hundreds, of tiny stalactites spiking down from the roof of his skull. It was, in short, unbelievable. But it had happened; and the more I obsessed over the utter pathology of it, the more I felt the need to write about it.

The story that resulted [“Shame,” May 1994] was not in any way conventional. I felt that, to honor the reality that had inspired it, its language had to reach a bit beyond realism, had to be strange and impressionistic. It ended up being the most experimental thing I’d ever written, and I figured it would never be published. Who was going to care about a misfit story about a misfit in prison?

Ashley Walker

Dallas, Texas

First published June 1991

Life’s tough patches are like having your car break down in a moribund desert town and being forced to wait it out while whatever is broken gets fixed or rebuilt. You are stranded. There are no friendly faces, no decent food, no clean motels. In this state of mind, I had hunkered down to wait for my psychic sandstorm to blow over. I didn’t tell my husband what a mess I’d become, but I figured he knew what was going on. All he had to do was look at me: staring into space, dragging around the house, reading one useless book after another, taking endless sickly naps.

“I’ve just subscribed to this,” he said one afternoon while I brooded on the couch, still in my nightie, smoking a cigarette. He flopped down a magazine. “I thought we’d like it.”

I looked at the cover with distaste: The Sun. I picked it up, glanced inside, and sighed. “I don’t know,” I said. Just then, I didn’t like any of my husband’s ideas.

“It’s got some good writing,” he said.

I looked through it again and tossed it beside the couch.

A few days later, I decided running might help, but I couldn’t muster the energy to do more than droop over the furniture. Early that morning, I sat spraddle-legged on the floor like a child, searching through a mongrel assortment of books for the words to motivate me, to wake me up — words to make me live again.

Mixed into the pile of books was that copy of The Sun, the one I’d discarded in my fit of gloom. Idly, I picked it up and thumbed through it. It was so early the windows were black and the moon was out. I began to read. From somewhere close, a sad dog howled. I read and read. I don’t remember what stories, what essays. I just recall a blend of voices — all of them imperfect and human. There are people just like me, I thought, and I knew right then: someday I would write for this magazine. Then I looked around and saw that the sun was fully up, and the day was already hot.

Alison Luterman

Oakland, California

First published October 1992

I remember when the first acceptance letter came six years ago, and along with it a short, handwritten note from Sy saying he liked my writing and wanted to see more. My heart sang for a week. I’d been published before, but never so warmly, so personally. I taped the note to my bathroom mirror so I could read it while I brushed my teeth.

I’m a writer who has to feel she is writing for someone. Otherwise, why bother? I have written for my parents, my friends, my husband, but until The Sun I didn’t feel as if I was speaking to the larger world. Once, a man from Austin, Texas, called and left a long, tearful message on my answering machine, saying he’d been crying all afternoon because of a story I’d written. Another reader sent me whimsical cards and letters that helped keep me going through a long, painful separation and divorce. To be a poet in America is mostly to be considered irrelevant, but The Sun’s readers have made me feel a part of their lives.

For its fifth anniversary, in January 1979, The Sun underwent its first official redesign, which coincided with the switch to a web press and a less expensive paper. Tom Cleveland’s sun face temporarily disappeared from the cover.

Gillian Kendall

San Martin, California

First published April 1992

Manuscript Reader 1997–present

In the mideighties, my friend Janina kept recommending that I read The Sun. “It’s a really good magazine,” she said. But I was up to my neck in really good magazines and not bothering to find new ones.

About five years later, en route to Shanghai to meet a ship on which I’d be teaching English, I stopped in Maui to see Janina. I read her the beginning of a strange story I was working on. She listened and critiqued it, and then, saying she’d be back in a few minutes, left me sitting in the shade with a cup of Kona coffee and a stack of Suns.

She was gone more than an hour. When she returned I told her I thought I’d found the right place to send my story.

I spent the next six weeks on board the Chinese ship. I taught just two hours a day. We had no ports of call, one ten-minute phone call a week, and one mail delivery at the halfway point. There was no radio or TV, or even other ships to look at, and I hadn’t brought enough books. So I spent the days copying over and editing the pages of my story by hand. I worked every sentence many times, and by the end of the trip I had the best story I’d ever written.

I sent “The Value of Trees” [April 1992] to Sy, along with ten dollars for as many issues as that would buy me. I got back a flattering letter saying that The Sun would buy the story, and later I received a check for the largest amount I’d ever been paid for my fiction. I used it to buy a friend’s painting, something I’d have forever.

Since then, my Sun earnings have bought me many durable goods, including a Walkman, part of a stereo, and a root canal. The wages I’ve received from The Sun as a writer — and lately as a manuscript reader — are precious, because I’m getting paid to do what I love. I write for The Sun in my truest voice and see the magazine as an intellectual community of friends. My recent essay “Protection” [April 1998] brought the most responses I’ve ever had to a piece of writing. I even got letters from a witch and a gun advocate, both advising me how to take care of myself.

Some years ago, I got a chance to visit the Sun office in Chapel Hill. I hadn’t expected it would be in a house. A stained-glass sun hung in an upstairs window in back, and a picture of the Dalai Lama occupied a prominent spot in Sy’s office, which was preternaturally tidy. Most surprising was how Sy looked. I’d pictured him as a balding, dark-eyed, slouchy man with a paunch. I was surprised to find Sy fair, tall, and trim. He was also funny and kind, and exhibited the sort of moment-to-moment awareness that could have been intimidating if not for his gentleness.

Last month, perhaps because of several recent address changes, my Sun didn’t come for the first time in about eight years. I felt as if a friend scheduled to visit had failed to arrive. I’ve begun to feel oddly connected to such writers as Poe Ballantine and Alison Luterman, whom I know only through reading their work in The Sun. The older I get, and the more places I live, the fewer lasting friends and communities I have. The Sun feels like both to me.

Dan A. Barker

Jacksonville, Oregon

First published December 1990

Convinced that building free vegetable gardens for poor people was worthy of national exposure, I wrote to Sy Safransky, asking if a local stringer could do an interview with me. Sy wrote back, encouraging me instead to write a personal essay about my work. In all my years of writing, his was the first heartfelt offer from a publisher to listen, so I took a chance. The resulting essay [“Giving Away Gardens,” December 1990] was reprinted in twenty or thirty other publications and helped to feed thousands of people.

I may have done the work, but it was Sy Safransky’s intellectual courage that opened the door. A great number of people owe him their deepest thanks, and I’m one.

Vicky Lindo Kemish

Boca Raton, Florida

Editorial Assistant 1976–1977

In 1975 I was one of the first “salespeople” for The Sun. I loved standing outside the Chapel Hill Post Office on those gorgeous North Carolina spring days and asking passersby, “Have you heard about The Sun magazine?” I was eighteen and needed a place to belong, a place to begin to grow up. The Sun provided the perfect niche.

The Sun office on winter mornings was toasty warm and filled with the aroma of fresh coffee. There was a churchlike quiet that I was determined not to disrupt, but, try as I might, Sy always heard my habitual scuff, scuff, scuff. Until he pointed it out, I’d never realized I dragged my feet.

Sy was devoted to his old Underwood typewriter, which sat on his desk like a monument to the written word. We’d have “breakfast” together in his office: coffee for him and unfiltered Camel cigarettes for us both. Coffee was as sensual as a woman to Sy, and the dance he did with its“forbiddenness” (caffeine, he believed, was bad for you) seemed only to increase his enjoyment of it. I hoarded the pearls of wisdom that Sy shared with me. He held my hand during my down times, and I stood by helplessly through his.

In 1981 I moved away from Chapel Hill permanently. For the next eight years I lived in Jamaica and Panama. At one point, I wrote to Sy saying that the magazine was becoming self-indulgent, that people were hungry, poverty-stricken, and ill, and that he should be addressing these issues in The Sun.

Sy either didn’t let my comment get to him or somehow found it in his heart to forgive me, because when we saw each other years later, he didn’t mention it. Maybe he always knew what I had yet to realize: that through The Sun he had been feeding the hungry, sharing with the poor, and sending hope to the hopeless.

Keith Eisner

Olympia, Washington

First published May 1994

As a beginning writer, you have to get published the same way a nineteen-year-old virgin has to get laid. Your world is divided by a river: On one side are all the people who’ve been published. On the other side is you. Common sense tells you that getting published won’t make you a “real” writer any more than having sex will make you a real lover. At writers’ retreats and workshops, you nod your head in sage agreement when the instructors (all of whom have been in print) tell you that being published is the least-important thing about writing. But, just the same, you want it.

Eventually, you get what you want. When my words were first accepted for publication (not in The Sun, but in a local monthly), I could hardly contain my excitement — or my impatience. I drove to the next town and waited at the printer’s for the first copy to come off the press. Holding that magazine in my hands, I felt a mix of emotions: Happiness, yes. Pride, yes. But also an unexpected disappointment. Is this it? I thought. Is this all there is?

For a while, I carried that publication with me wherever I went, introducing it into conversation whenever possible, trying to make the experience last. But it couldn’t last forever. Eventually, the truth dawned on me: The rush — whether of sex or drugs or publication — lasts for only a few minutes or hours or days. Before long, no matter how many bestsellers you’ve written, how many favorable reviews or big checks you’ve received, you have to do it again. Alone. And it’s as fresh and intimidating and heartbreakingly tedious as it was the first time.

I like writing for The Sun. I like the way the editors inspect my submissions, tap on the walls and floors, sound the ceiling — try to make the house of my words stronger and truer. I appreciate their unromantic sense of craftsmanship, their no-nonsense commitment to the exacting task of writing. When part of me asks, Is this all there is? I imagine The Sun replying, “Yes, and guess what: you get to do it all over again tomorrow.”

Pamela Tarr Penick

Austin, Texas

Editorial Apprentice/Assistant Editor 1992–1994

Here in Texas, the magazine would likely be called El Sol. Sounds like soul.

The soul of the place wasn’t the house, but you could see it reflected there. Modest white two-story dwelling. Inviting porch swing. Sunny rooms. Scuffed yellow wood floors. Creaking desk chairs. I like to remember the quiet late afternoons in my small second-floor office, windows open, a breeze pushing at blinds slanted to mellow the heat of the setting sun.

I started working at The Sun in March 1992, an eager editorial apprentice. Two years later, having worked my way up to assistant editor, I reluctantly quit to move out of state. Today I realize that I’ve been a full-time mother for as long as I worked at The Sun. There are more similarities between the two jobs than you might think. For one, there’s the never-ending cleanup: scraping away food, picking up toys, and doing load after load of laundry versus editing a manuscript for the second or third time, then proofreading, proofreading, proofreading. In both, there are daily challenges to rise to: my sleeplessness and my toddler’s temper tantrums versus deadline crunches, proofreading slip-ups, and printer errors. And then there’s the reason I bother with it all: watching the object of this hard work and devotion grow into something apart from me, yet still containing a part of me.

Ken Klonsky

Toronto, Ontario, Canada

First published November 1989

The most important story of my life was the most difficult one to tell. My mother left home when I was a teenager without even a note as to her whereabouts. For most of my adult life, unacknowledged feelings of rejection and abandonment formed my attitudes and my temperament, poisoning many relationships that might otherwise have saved me years of suffering. When I discovered The Sun, I discovered a place where such stories were told, a community of souls who took this kind of work seriously.

I sent my story to Sy in the explosive, subjective form in which I’d written it, and it fell to then assistant editor T. L. Toma to employ some gentle surgery and bring the piece under control. At the time, I saw myself as an emerging talent who would one day join the pantheon of renowned Canadian writers — a foolish and grandiose dream.

I don’t think I have ever written anything as good again, but I am not filled with disappointment and regret. It was enough to have reached out in my loneliness and confusion and shared that story from my heart in The Sun.

Jim Ralston

Petersburg, West Virginia

First published January 1983

In 1982, I received a letter from Sy saying that he wanted to print an excerpt from my book, The Choice of Emptiness, in The Sun. I was thirty-five years old and living in a log cabin with an outhouse and a wood-burning stove. I was washing my dishes in the creek. It was winter.

Well, I’ll be, I thought, standing by my snow-peaked mailbox, my hands full of frost-stiffened bills and junk mail. At long last, a real publication. I say “real” because my book was self-published, a collection of essays that had first appeared in a local newspaper. Somehow, Sy had ended up with a copy.

The Sun was only eight years old then, still printed on rough paper, but I couldn’t have been happier. I had been writing almost every day since my early twenties and was sometimes embarrassed by how little I had to show for it. I was even more delighted when my complimentary copies arrived and I discovered my words shared an issue with those of Ram Dass.

Recently, I was asked to speak at a writers’ conference on how to get published. The participants were looking for tips on how to catch an editor’s eye, how to get off the “slushpiles” — the huge stacks of unsolicited manuscripts that crowd editorial offices everywhere. I told them that, instead of waiting to be found, they might do well to get published in their hometowns, let their career build bit by bit, even publish themselves, if need be, as Whitman and Thoreau did (as Sy did when he started The Sun, for that matter). I suggested that if they worked their way up from the ground floor — or even the cellar — focusing on content rather than lucky breaks, the odds were good that the right editor would find them one day, just when they were least expecting it.

That was my experience, anyway.

Susannah Joy Felts

Chicago, Illinois

First published January 1997

Manuscript Reader 1997–1998

When it was time to dig into a fresh box of manuscripts, I would sit in the tiny dormer of my dirty, dusty second-story bedroom, pick one from the top of the pile, and begin reading. Occasionally, I’d pause to watch screeching bluejays dive-bomb my cat in the front yard or to listen to the firetrucks come and go across the street. I’d prop my feet up on the wall, surrounded by stacks of other people’s writing, and imagine my own work someday, somewhere occupying a similar position in another manuscript reader’s life. Often it seemed only wishful thinking.

Evaluating other writers’ work, I’d sometimes be inspired to the gills, constantly interrupted by thoughts like If she can do it, by God, so can I. But then, when it came time to stop, I’d glance over at my computer, sigh, curl into a half-fetal position on my futon with a book or the latest issue of Harper’s . . . and soon be asleep.

On other, more emotionally unsure days, all a writer had to do to make me tear up was pour his or her heart out in a cover letter. I could just see the solitary writer agonizing over a final draft, sticking it in the envelope, and standing in line at the post office, all the while praying silently that the stranger whose eyes read it on the other end would be moved and impressed.

I was that inscrutable stranger, allowed access to the innermost thoughts and most private details of other people’s lives. Occasionally a writer’s words touched me deeply, even if the piece wasn’t accepted, and I never neglected to mention this in my rejection note. In some respects, I believe, this should be as gratifying to writers as an acceptance letter and a promise of money, because they will always know that they made a difference in someone’s life.

Gene Zeiger

Shelburn, Massachusetts

First published January 1993

I ’ve published numerous essays in The Sun, but it was a paragraph or two of mine in Readers Write that elicited the most compelling response. The topic was “The End of the Day” [December 1995], and in my piece I described how down I get in November, when the days become so short; how sometimes I just lie on the couch around 5 P.M., full of angst and self-pity. I ended with the line: “No one here but me, and I am not enough.”

A few weeks later, I received a very peculiar letter from Long Island. The handwriting was barely legible, and what I could read made no sense. All I could figure was that the letter-writer had gotten my name from somewhere (perhaps the piece in The Sun) and wanted to tell me something very unhappy, but I couldn’t decipher what. I shrugged and threw the letter out. A week or so later, the phone rang. I dragged myself from the couch, where I’d been feeling angst-ridden and self-pitying again, and answered it. “Hello,” a woman’s voice said. “I wanted to call and apologize for the letter I wrote you the other week. I’m afraid I was really drunk.” She explained that she’d read my little essay in The Sun, and it had really touched her. “I’m in terrible shape,” she said. “My husband died a few months ago. We were married for fifty-two years, and I just can’t adjust to living without him.” Again, she apologized for the letter, and I assured her that it was fine and said I was sorry to hear about her husband.

“And what, dear, is your problem?” she asked.

The pause that followed was difficult to say the least. “Well,” I said at last, wishing for a better tragedy to relate, “I just get kind of depressed in the fall. . . . You know, how it gets dark so early and all.” I waited for her reply.

“Oh,” she said. “Well, you’re a very good writer, and you said what I feel a lot better than I could, especially that part about being alone and how it’s just not enough. Thanks, dear. Goodbye now.” Then she hung up.

Andrew Ramer

Menlo Park, California

First published January 1988

For more than a million years, human beings lived in small groups, and everyone sang, danced, and talked together around the fire. Now the fire is gone; the tribe is gone. Yet for some of us, there is The Sun. I didn’t even know it existed until Sy published an excerpt from my first book, little pictures. Since then, in addition to numerous Readers Write pieces and an occasional letter to the editor, six of my works have appeared in The Sun: two chapters from an unpublished novel, two sections of a book on dying (also unpublished), and two short stories out of the 331 I’ve written — I counted — since 1974.

I am a writer because my third-grade teacher, Mrs. Winetsky, read us Edgar Allan Poe’s poem “The Bells,” and it so enthralled me that I started writing that very afternoon. I am also a writer because of my mother’s mantra: “What makes you think you have anything to say, young man?” Writing was secret talk. (No wonder Emily Dickinson became my favorite poet.) Paradoxically, the private act of writing emerges from that ancient public impulse to talk around the fire. To me, being in these pages has been an enormous gift. Here I can sing — and be sung to, as well. My soul is fed by each issue, even though at times I don’t like what I read. But then I remember my biological family, and how little I agree with them, and how much I still love them.

The Sun means the world to me — the real world: small, close, familiar. In a culture where there’s room only for bestselling books by authors we have no connection with, The Sun is a taste of how the world should be, a tribal gathering on paper, a meeting place, singing place, dancing ground.

Julie Burke

Snow Camp, North Carolina

Art Director 1996–present

As I sit down to write this, the cover of the issue you are reading is a complete mystery to me. I should know by now what it will look like, but the design is still up in the air, because Sy and I can’t agree. For the past year, we have discussed redesigning the cover to celebrate the twenty-fifth anniversary, as well as to make it more congruent with the inside of the magazine. As expected, this particular project has been my most difficult undertaking so far.

When I left Virginia to work for The Sun, I fretted over the decision to leave my dearest friends and my favorite town. I crossed my fingers in hopes that this job would be meaningful, that maybe, just maybe, it would live up to my often naive expectations. I was not disappointed.

For the first time in my life, I am lucky enough to work in an environment where the beauty and truth of the product resonates through even the most menial chore performed on the most extraordinarily ordinary day. Paper towels? Recycled. Services? Local businesses. Coffee? Organic. Attempts to gain new subscribers? Respectful, always honest, and disdainful of unscrupulous sure-fire techniques. And my everyday interaction with Sy? If I try to describe it, I will surely make it less than it is. I can only compare it to a great talk with a best friend, a deep moment with an honored counselor, a tender look from a beloved parent.

Sy is probably going to cut most of that. He is embarrassed by this sort of public praise. So why give it? Because I’m following his example: Sy doesn’t conserve his admiration and respect for others. Too many of us seem convinced that our kindness is in limited supply; we squeeze out drops, mindful of how much is left. But Sy’s supply seems bottomless. I imagine, in fact, that every issue is a long love letter from him to the readers.

From the very beginning, each change I’ve proposed at The Sun has been met with cautious consideration: Is it confusing? Is it respectful to the readers? Beauty aside, is it easy to read? Such questions are at the forefront of what we do here. And almost without exception, I am grateful for this hesitancy, because it reminds me not to forget the reader.

Unfortunately, it also means we still cannot agree on how the new cover should look. I envy you, the reader, for your knowledge of how this particular drama will end. Ultimately, however, I’m delighted by my dilemma. At other jobs, it might be easier to come up with a good design, put it on the cover, and move on. But it is only because I have the job, the boss, and the co-workers I’ve always dreamed of that my days here are sometimes so challenging. Whatever design you see on the cover of this issue, you can be sure it has been through the wringer, that everyone at The Sun liked it, and that we are holding our breath, hoping that you will like it, too.

Mark A. Hetts

San Francisco, California

First published August 1994

On a whim, because I thought somebody there might enjoy it, I started sending my self-published quarterly newsletter, Mr. Handyperson, to The Sun. One day, the editors notified me that some essays from the newsletter were going to be reprinted in the magazine. I was honored and ecstatic. It seemed a nice little notch on my writer’s belt. (Or is it desk leg? Pencil? What do writers put notches on, anyway?) I viewed publication as an end in itself, but, much to my astonishment, it was merely the beginning of a delightful, joyous correspondence with other readers and contributors. In the succeeding months, I got literally hundreds of letters with inquiries about my newsletter, supportive remarks about my writing, and stories of people’s own experiences. This last type of response was the most satisfying. I have always thought that good writing doesn’t make people sit back, shake their heads, and say, “That was good writing,” but rather makes them immediately think of their own stories and want to write them down.

I ended up nearly doubling the circulation of my newsletter, but, even more, I became friends with a whole new group of letter-writers and storytellers — among them some of the most thoughtful, caring, creative, and delightful people I have known.

It seems remarkable to me that a mere magazine should have created such a sense of community. I don’t enjoy every single thing in The Sun — hell, I don’t even like one or two of the pieces I’ve had in it all that much — but there is always something in each issue that moves me to tears, or gets me angry, or makes me laugh out loud. Always.

Marc Polonsky

Berkeley, California

First published November 1986

When I first read The Sun in 1985, I was convinced that divine inspiration was behind the magazine. I treated my copies like rare spiritual treasures and shared them like sacraments. I remember telling people, “This magazine has come into my life. . . .”

I wrote to Sy about one of his essays, and to my surprise he responded. (Years later, my friend Patrick Miller would comment, “In the early days, I loved to send work to Sy just for the pleasure of getting his rejection letters.”) I submitted a few stories, which came back with encouraging comments. I pledged that someday I’d write something he’d want to publish.

In 1986, I took part in the cross-country, nine-month Great Peace March for Global Nuclear Disarmament. On the way, I sent Sy a short piece I’d written about walking in the march. Months later, my subletter told me on the phone that I’d just received the new issue of The Sun. “I liked your essay on the march,” he said. I was stunned and deliriously happy.

When the march concluded in Washington, D.C., a friend suggested, “You’re so near North Carolina, why don’t you go and meet this Sy Safransky?” So I called The Sun’s office. “You know,” Sy said, “I was just saying to someone the other day that I’d like to meet you, and now I’m going to get my wish.”

I arrived at the office on Rosemary Street in Chapel Hill feeling like a pilgrim who’d reached a sacred station. Sy observed my awe with affectionate amusement. “I didn’t know what to expect,” I said. “I had this larger-than-life image of you.” He laughed and said, “No, I’m just a schlep.” That night, Sy and his wife, Norma, took me out for Mexican food, and Sy gave me a complete set of back issues. It was like discovering the magazine all over again.

D. Patrick Miller

Berkeley, California

First published December 1982

I don’t mean to brag, but it is through The Sun that I “discovered” novelist Tim Farrington, author of The California Book of the Dead and Blues for Hannah. I read a story of Tim’s and recommended it to my literary agent and wife-to-be Laurie Fox — and the rest is publishing history.

Then there was the time a woman called from the East Coast and said her psychotically disturbed son had read one of my Sun essays and had decided he just had to speak to me in person. He’d taken off with all his worldly belongings and my address — published with the essay — in hand. Would I give her a call if he showed up? (I’m still waiting.)

Some people have practically begged me to interview them for The Sun, while others, when I’ve told them where I wanted to place the interview, have said, “The what?” (Just try explaining The Sun to someone who’s worried about his or her public-relations profile: “Have you ever heard of Sparrow?”) I was once involved in an ill-fated romantic correspondence with another Sun writer — ill-fated because the recipient of my attentions kept writing back and saying, “Are you nuts?” And I was plainly told that I was nuts by the late and fiery Buddhist Stephen Butterfield for writing an essay opposing capital punishment.

For me, that’s the classic Sun encounter. Only in these pages can you meet Buddhists for the death penalty and other paradoxical types who will say — with the intensely mild-mannered encouragement of Sy Safransky — almost anything.

Sue Tremblay

Miami, Florida

Business Manager 1992–1996

From August 18, 1992, to June 16, 1996, I was The Sun’s business manager. The dates of my employment are burned into my mind because it was my First Real Job. I was twenty-two years old, one year out of college, and desperate to work in publishing, to do something more than put in forty hours a week and get a paycheck in return.

At first, I didn’t fit in: my wardrobe was too preppy; I watched too much television; I ate meat, for God’s sake. But The Sun and I learned to appreciate each other. The magazine grew while I was there (partly me, partly luck), and I grew, as well. I would sit in my office — a big first-floor room with French doors, wood floors and a nonworking fireplace — and feel at peace. I loved my four years at The Sun. The job was a perfect fit for my competitive, creative, difficult nature. And Sy was a natural mentor, antagonist, and friend.

Last Sunday was my twenty-ninth birthday. When I was eighteen I established three goals to reach by the time I turned thirty: run the Boston Marathon, write a novel, and make a million dollars. I haven’t done any of these things, not a one, not even close. And now there’s less than 365 shopping days until Christmas. Oh sure, I’ve done a lot of other things: married my best friend, finished an MBA, acquired a great job making good money. And yet I feel as if I’ve failed.

I can imagine sharing this feeling with Sy right now; I can see him in his squeaky chair behind his big oak desk, his left foot bouncing up and down over his crossed knee, his eyes crinkling up as he smiles. He doesn’t offer an explanation, just sits there silently, as if he were my shrink, waiting for me to come up with my own answer.

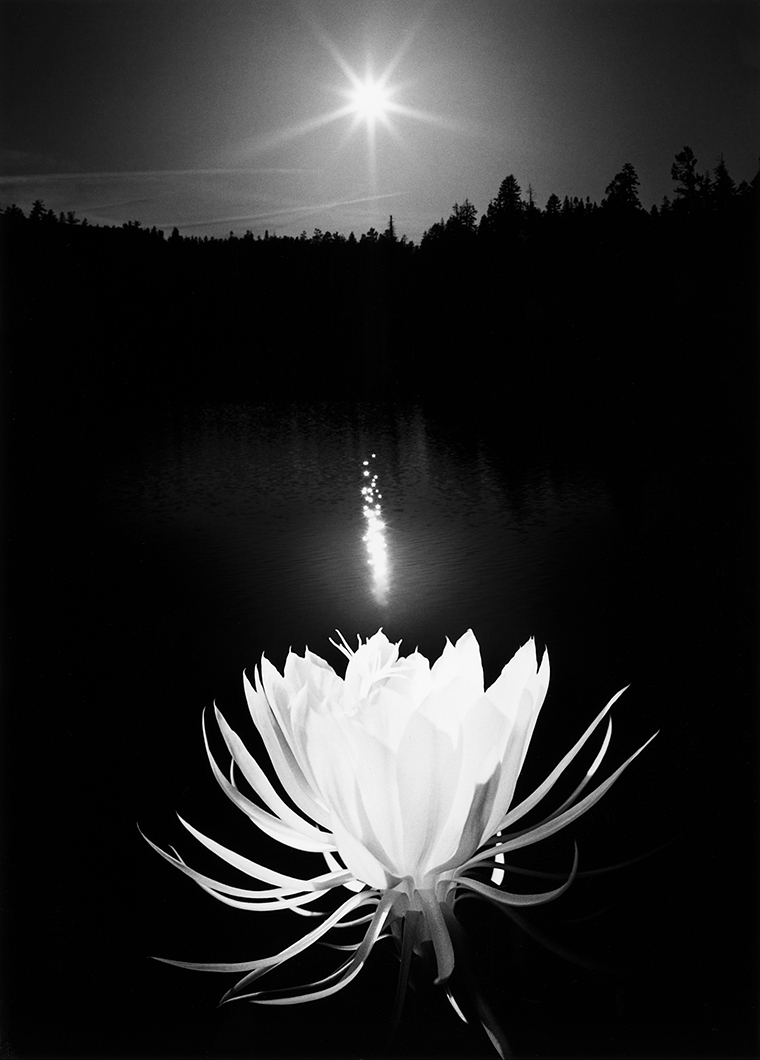

This familiar cover format first appeared in January 1992. It was part of an overall make-over by designer Sue Koenigshofer. The photo here is by Hella Hammid.

Mary Sojourner

Flagstaff, Arizona

First published July 1991

A few years ago, I sent my story “Squirrel” to The Sun, waited for a few months, then found the welcome acceptance letter in my mailbox. “Squirrel” was a different piece, closer to essay than fiction, relentlessly dark, its sorrow relieved only by cameos of Yellowstone’s geothermal Black Basin. The ending was bittersweet, solitary — and unarguable.

Andrew Snee, The Sun’s assistant editor, read it differently. He believed there was the possibility of lightness, a little goofiness, even, to cut the gloom. I knew what I knew. He knew what he knew. I faxed. He faxed. We talked for an hour on the phone and could not resolve our differences. I am, at best, a grouch; at worst, a prima donna. I decided Andrew was hopelessly young and hopelessly male, and finally withdrew the piece.

With any other magazine, that would have been the end of the story. I was raised German Catholic, and once you screw up with me, you’ve screwed up for good. I have never become friends with an ex-lover, or gone back to a city in which I knew heartbreak. If I crack a cup, I take it to the rock pile and smash it. There is no mending.

The Sun, unaware of my high-principled snit, continued to arrive in my mailbox. And I continued to read, to love some works, be indifferent to others. And, always, I marveled at our craft, at the writing, at the editing, at the passion that shouts and glowers in The Sun’s pages.

I have treasured, endured, or harbored murderous rage toward editors of other magazines and presses: the woman who sent me a luminous stone egg for my writing altar; the creative-writing-program journals that never send back my self-addressed, stamped postcards; the editing intern’s chipmunk voice on the phone, “I didn’t have time to read the whole collection, but I’m pretty sure it doesn’t hang together? You know?” And slowly I have realized that what happens on the editing desks of The Sun is not about brownie points, knee-jerk responses, or naiveté. The work at The Sun is craft — patient, delicate, and straight from the heart.

Andrew Snee

Raleigh, North Carolina

Assistant Editor 1994–present

Occasionally, someone will ask me, “So, what’s it like being an editor?” Here’s the answer I’ve come up with: Imagine it being your job to tell people, “I really like your hair; it looks great . . . except for that one curl sticking up in back. Here, let me fix it.” At which point you produce a pair of scissors and start toward them.

I’m constantly amazed when the authors whose work I edit don’t respond the way we all would to that maniac with the scissors. Like one’s appearance, a piece of writing — especially the kind that appears in The Sun — is personal. You don’t let just anyone tamper with it. So I do my best to be an editor whom writers can trust, to be deserving of the confidence they (sometimes reluctantly) place in me. And when I show them the changes I suggest they make, I desire their approval as much as they might desire mine.

I’m happy to say my approval rating is good. I have a thick file of thank-yous and only a thin one of screw-yous, which I keep as a reminder not to get cocky.

I received another, more important reminder a couple of years back, when I thought I might leave The Sun, and Sy advertised for my replacement. Candidates came pouring in, some from far away, many of them highly qualified, and all of them wanting my job. Suddenly, I felt like the guy with the beautiful woman on his arm, the guy whose place other men long to take.

I didn’t leave, of course, but my brief stay in limbo served its purpose: to remind me how lucky I am. At a time when so many jobs offer little except alienation, burnout, and lowered expectations, I possess that rare, sought-after prize: fulfilling work. I have Sy and The Sun to thank for it.

Sarajane Archdeacon

New York, New York

First published October 1993

Sy’s reluctance to advertise The Sun’s twentieth-anniversary symposium at the Omega Institute in Rhinebeck, New York, meant that only eagle-eyed readers who saw the small-print announcement on the Correspondence page even knew about it. So it was a miracle that several dozen of us showed up, some coming from as far away as California. There weren’t enough chairs, so most of us sat on the wooden floor of the well-lit room. We were a wildly diverse crew in age, sex, race, religion, and income bracket, yet gathered in a harmonious circle.

Antler read a poem on the orgasmic nature of just about everything, and then another with a homoerotic theme. A skeptical older woman asked if all the boys in today’s world behaved like the boys in his poem. Antler said yes. Enchanted, the woman moved closer to him.

Later, Sy passed out a handful of manuscripts and requested our opinions on them. Within a moment, we went from shy and cautious to licensed to kill: our targets, the unfortunate authors of these photocopied handouts. We were merciless in our editorial judgment. Serious flaws outweighed any merit in just about every manuscript.

Eventually a silence fell over us. Someone asked Sy if this was how works were selected at The Sun. He said he always listened to what his editors and manuscript readers thought, but, in the end, he was the judge. If he really liked a piece enough, it got published.

“And the manuscripts you just passed out for us to criticize,” someone else asked, “have they all been rejected?”

“No,” Sy said with a grin, “they’re in the next issue.”

Antler

Milwaukee, Wisconsin

First published July 1991

I first learned about The Sun from Ashia, who lives in my housing co-op along the Milwaukee River. She gave me a stack of back issues, thinking I’d like them. I did, especially Sunbeams, as I’d always been a lover of memorable quotations. The magazine as a whole seemed to carry onward and further evolve the best of the sixties counterculture, so I decided to submit some poems. My first submission was rejected. My second submission was rejected. My third and fourth were rejected. Undaunted, I sent some riskier work, and to my surprise almost all of these poems were accepted. Since then, my poetry has appeared in more than twenty issues of The Sun.

I thank The Sun for liking my poems at a time when too many editors and critics dismiss philosophical/political/ecological/narrative poetry in favor of poetry that is random gobbledygook. In some instances, poems that no other magazine would print — like “What Every Boy Knows” [September 1995], about boyhood masturbation — have appeared in The Sun and, as a result, have been reprinted and anthologized elsewhere. “Somewhere along the Line” [May 1992], one of my most outrageous poems (I couldn’t believe The Sun printed it), went on to win a Pushcart Prize (I couldn’t believe this either). After my poem“Zero-Hour Day Zero-Day Workweek” [December 1992] was published in The Sun, I was invited to read it on a National Public Radio program about the future of work in America. The last poem of mine that The Sun printed — “Now You Know” [December 1997], about the fact that male babies in the womb have erections five times a day — caught the attention of David Del Tredici, one of America’s foremost classical composers. He wrote me asking permission to set the poem to music.

Josephine Redlin

Fresno, California

First published September 1995

I always smile when I think of getting my first Sun, the September 1995 issue, which had one of my poems in it. I had envisioned sending copies to my family back in South Dakota, but yikes! How would the folks back home take Antler’s masturbation poem“What Every Boy Knows”? Not to worry, I thought. I’d just wait for the next issue in which I had a poem. But that one had a bold photograph of a naked male statue on the cover. I could already hear the comments: “And to think, after all those years she spent in Catholic school.”

As I became more familiar with The Sun, I saw that, in addition to its ability to shock or challenge, it had a reverent quality all its own. In every issue there is a gentle handling and nudging of the fragile human spirit.

Today The Sun occupies an old but well-kept two-story house at 107 North Roberson Street in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. The landscaping is the work of Gregory Piotrowski.

©Gregory Piotrowski

Lynda Malone

Chapel Hill, North Carolina

Office Clerk 1997–present

When I was hired for this job, The Sun was not new to me. I was here in Chapel Hill when Sy produced his first issue. My ex-husband once had a poem in The Sun. My daughter and Sy’s even attended the same preschool. Whether dropping off his little girl or hawking his magazine on the street, Sy appeared intense and slightly wild.

Through the years, picking up the occasional issue of The Sun, I would think, Gosh, it’s still around. When I applied for my position, part of the process was to read and comment on a couple of recent issues. Not only was The Sun still around, I found; it had matured and thrived. I sensed something important in the works for me.

Working here is marvelous, which is not to say it’s easy. There’s stress. (I am still in awe that so few people can produce something so good without killing themselves.) I’m tired when I go home. My back hurts when I lift boxes in the warehouse. But there has yet to be a day when I did not look forward to coming to this old house. Gail Godwin, one of my favorite writers, has written about “how important it is to be doing something you like doing every day until the end of your life.” I’m doing it.

Cat Saunders

Seattle, Washington

First published December 1990

When I first encountered The Sun, I was intrigued by its lack of advertising and its abundance of melancholy. I submitted an interview with Ram Dass, which brought me my first check for published writing. Afterward, I stayed in touch with Sy. I’d write long-winded letters, as is my bent, and he’d almost never respond, as is his inclination. Now and then we’d exchange answering-machine messages, and, rarely, we’d talk in person on the phone.

I was overcome with shyness every time I heard Sy’s voice. His ten-second messages would take my breath away. I realized I had a crush on Sy, though I’d never even seen him. The truth was, I didn’t need to see him. His voice was enough. It came into my body like a white-hot wind and wrapped itself around my heart.

At first, this was confusing. After all, I lived across the country from Sy, and we were both in love with other people. Eventually, I decided to simply enjoy my feelings, the way a schoolgirl enjoys the adolescent urges that will never see the light of day. I figured that if I let these feelings be, they’d teach me something.

Over time, the crush revealed its true nature: it was merely a reminder of what I valued in myself. When I heard Sy’s voice, it tugged at my heart like a fish biting at a line. But if I pulled on the line, I wouldn’t catch Sy. I’d catch certain parts of my own soul: authenticity, tenderness, attentiveness, poignancy, compassion, integrity, courage.

It’s not that other friends don’t touch these same parts of me, but Sy does it just so. It’s the same with The Sun. There are many magazines that delight me, make me laugh, and inspire me to reexamine my thinking, but only The Sun can do it just so.

Carolynn Schwartz

Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada

Business Manager 1989–1993

I remember walks with Sy. Talking over business decisions, ethical questions, our personal lives. Moving slowly through a quiet neighborhood near the office, perhaps never quite sure where we were, but never quite lost either. Our words following suit. Rarely knowing, at the outset, what we would talk of that day, our path unfolding without conscious effort. Returning more peaceful, clearer, not oufitted with shiny new maps, but with some greater understanding of where we were when we started.

Heideh D. Kabir

Alexandria, Virginia

Office Assistant/Office Manager 1990–1993

I was twenty-two and fresh out of college when I saw Sy’s ad for an office assistant. I figured a job at a magazine was a good place for an English major to start her career. Sure, it didn’t pay much, but everything about the interview felt right, from the thoughtful questions Sy asked me to the gentle and welcoming feel of the office.